Guest post by Brigitte Knopf

With his encyclical “Laudato Si” the Pope has written more than a moral appeal without obligation. He has presented a pioneering political analysis with great explosive power, which will probably determine the public debate on climate change, poverty and inequality for years to come. Thus, the encyclical is also highly relevant to me as a non-Catholic and non-believer; the implications of the encyclical are very apparent through the eyes of a secular person.

The core of the encyclical makes clear that global warming is a “global problem with grave implications: environmental, social, economic, political and for the distribution of goods” (25 – where the numbers refer to the numbering in the encyclical). The reasons identified are mainly the current models of production and consumption (26). The encyclical emphasizes that the gravest effects of climate change and the increasing inequality are suffered by the poorest (48). Since we face a complex socio-ecological crisis, strategies for a solution demand an integrated approach to combating poverty (139). So far, however, governments have not found a solution for the over-exploitation of the global commons, such as atmosphere, oceans, and forests (169). Therefore, the encyclical focusses on actors, such as non-governmental organizations, cooperatives and intermediate groups (179) and calls for a dialogue between politics, science, business and religion.

The encyclical is, with 246 individual points, too extensive to be discussed in here in its entirety, but three aspects are particularly noteworthy:

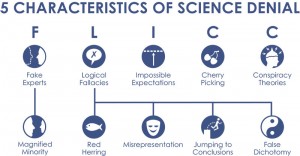

- it is based unequivocally onthe scientific consensusthat global warmingis taking placeand that climate changeis man-made; itrejects thedenialof anthropogenicwarming;

- it unmasks the political and economic structures of power behind the climate change debate and stresses the importance of non-state actors in achieving change; and

- it defines the atmosphere and the environment as a common good rather than a “no man’s land”, available for anyone to pollute. This underlines that climate change is strongly related to the issues of justice and property rights.

[Read more…] about Heaven belongs to us all – the new papal encyclical

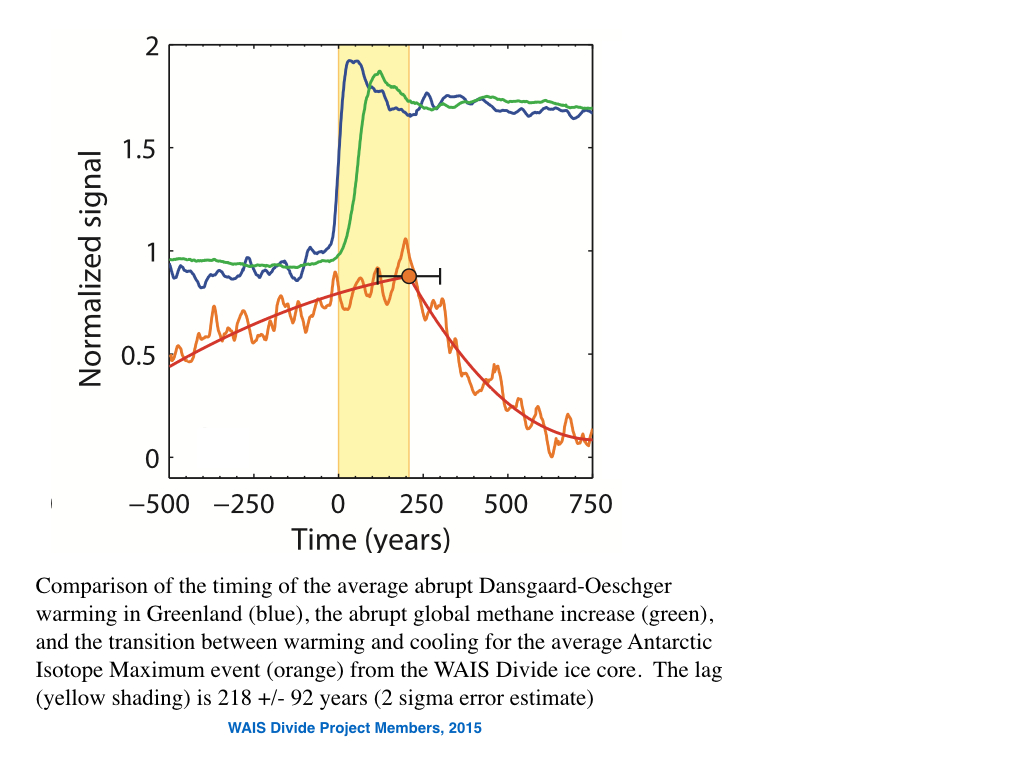

In 2001, Prof. Richard Lindzen and colleagues published his “iris hypothesis”

In 2001, Prof. Richard Lindzen and colleagues published his “iris hypothesis”