While there have been some recent set-backs within science and climate research and disturbing news about NOAA, there is also continuing efforts on responding to climate change. During my travels to Mozambique and Ghana, I could sense a real appreciation for knowledge, and an eagerness to learn how to calculate risks connected to climate change.

Recent events have shown incredibly high rainfall amounts that have devastated cities and countries, as well as droughts that have exacerbated the risk of wildfires. It is well known that global warming gives more extreme rainfall, and this is primarily explained as a result of warmer air being able to hold more humidity. It is, in other words, the Clapeyron-Clausius equation that describes how the water vapour pressure relates to temperature.

An additional explanation for extreme rainfall amounts is how daily rainfall is unevenly distributed over Earth’s surface area. There are now several papers documenting that the daily precipitation falls on a diminishing fraction of Earth’s surface over time, based on satellite data, reanalysis data, and global climate model simulations (Dobler et al., 2024 and references therein).

Changes in how rainfall is distributed over Africa can explain both flooding as well as droughts, and it is important to derive reliable information about the probability of heavy rainfall in order to be prepared for what the future climate will bring.

It is urgent to start climate change adaptation because of the rapid global warming (e.g. pulse.climate.copernicus.eu) and global statistics show that temperature and rainfall have already become more extreme. Also, climate change adaptation may send a message of the urgency and importance for mitigation.

In Mozambique I helped organise a CORDEX Flagship Pilot Study (FPS) workshop in Maputo where we worked on capacity building based on an open source tool for empirical-statistical downscaling. This tool is useful for studying consequences of climate change and providing valuable information for climate adaptation (Benestad et al., 2025).

One particular type of adaptation measures is connected to climate and health which is going on in Ghana. The annual meeting of the SPRINGS project was held near Akosombo in the Volta catchment, and one of its aims is to provide estimates of future rainfall to feed hydrological models in order to calculate the water quality and model the spread of pathogens that lead to diarrhoea outbreak.

This knowledge will be used for policy-making and intervention strategies for both water management and health planning. To get a better understanding of the local situation, we inspected a pumping station, as shown below, with water treatment and water supply to the communities.

The water provided by the pumping stations and the water treatment plants, however, doesn’t always cover all needs, and the alternative is to fetch water from the Vota river.

Manure and feces on the ground and in the fields spread into brooks and rivers when there is heavy rainfall, and we need robust estimates of how often we can expect days of heavy rain to assess future risks of such health problems.

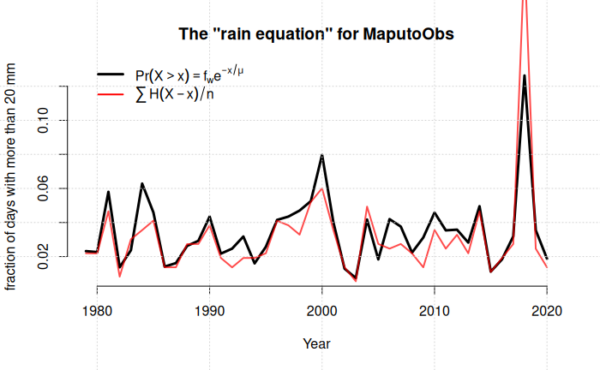

We use a very simple formula to estimate how often we can expect days with heavy rainfall, and the graphics below gives an example of observed (red) and calculated (black) annual frequency of days with more than 20 mm in Maputo, Mozambique. A similar calculation for Tanzania gives a similar good match, and we expect to find a similar match for rain gauge data from Ghana once we get access to it. This calculation is only based on the annual wet-day frequency and the wet-day mean precipitation (Benestad et al., 2025).

) and wet-day mean precipitation (

) and wet-day mean precipitation ( ). It shows that the simple formula can give an approximate number of days with heavy rainfall per year (here shown as number of days divided by 365.25 days).

). It shows that the simple formula can give an approximate number of days with heavy rainfall per year (here shown as number of days divided by 365.25 days). Both the workshop in Maputo and the SPRINGS project exploit this simplified and approximate estimation of heavy rainfall, which is a step towards extreme rainfall amounts, but nevertheless not quite sufficient for rainfall amounts in the excess of 100 mm/day.

Another important part of the SPRINGS project is the co-production of knowledge, involving a diversity of disciplines and cross-disciplinary collaborations. The connection between academia and the scientific community on the one hand, and the society on the other, is becoming increasingly important. Climate change is making the news in various ways, and challenges for Ghana involves both migration pressure and flooding.

We also know that similar problems can be expected in both Europe and North America, and that climate change affect animal and human health.

Another thing that I like to emphasise is that we have the necessary knowledge about climate change based on science and data. The Earth is continuously monitored through satellites, instruments on the ground and in the air, and Earth’s climate is reproduced through extensive model simulations (If you cannot get the information from American sites, there is the Copernicus Climate Change Services; “C3S”).

We also know what is needed to stop global warming: the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases such as CO2 and methane must stabilise, and the forests must be protected.

References

- A. Dobler, R.E. Benestad, C. Lussana, and O. Landgren, "CMIP6 models project a shrinking precipitation area", npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, vol. 7, 2024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00794-z

- R.E. Benestad, K.M. Parding, and A. Dobler, "Downscaling the probability of heavy rainfall over the Nordic countries", Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, vol. 29, pp. 45-65, 2025. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/hess-29-45-2025

Thank you for your inspiring work Rasmus and for explaining it to the wider community.

Thank you for this article. I recently found an African magazine, The Continent which lacks some modern formatting/scrolling conveniences, but provides a window on another part of the world.

On page 6 of 27 page PDF at https://www.thecontinent.org/_files/ugd/287178_1966ab5738d54cd2a3194d5ddae6d756.pdf [issue 192. march 1 2025]

“Namibia: Oil kaiju champing at their drill bits

“Petrochemical giants like Total, Shell and Chevron are scrambling to strike oil in the Atlantic off the Namibian coast. Galp, a Portuguese oil and gas company, said this week that it had found some.The state petroleum corporation has a 10% share in the venture so some money might stay on the continent. Which should totally make up for the whole world-on-fire thing.”

& page 10 of same issue

‘We prepared for a natural disaster – just not this one’: Botswana was overwhelmed by the rapidly changing climate. As the world gets warmer, and its weather less predictable, it will not be the only one

“Rain is a scarce and precious resource in Botswana, a mostly arid country. This scarcity has fuelled a collective yearning for rain that is fundamental to Batswana culture. …. In particularly dry years, it is not unusual for the president to ask the country to come together to pray for the heavens to open.

“Last week, nearly half a year’s worth of rain fell in 24 hours.

“In Gaborone and surrounds, it rained until cars began to float down the streets of the capital. It rained until bridges and walls collapsed, and people were swept away by the rising waters. Fifteen people were killed. It rained until the Gaborone Dam, which just a few months ago was two-thirds empty, began to overflow.

““After a prolonged period of drought caused by El Niño, the rains were influenced by the remnants of Tropical Cyclone Dikeledi, which came from Mozambique and South Africa””

Let them drink oil.

We’re a special species, for sure

Juste une question Mr Rasmus : Le Mozambique et le Ghana sont sujet aux catastrophes naturelles depuis des siècles. Pour le Mozambique par exemple, on sait que cette région d’Afrique est confrontée, depuis que ces événements sont répertoriés (plus de 80 ans), à des phénomènes extrêmes, notamment des inondations et des sécheresses : cyclones, débordements du fleuve Zambèze, le phénomène El Niño pour les sécheresses et les feux de forêt.

Pour le Ghana, des archives montrent que des sécheresses notables sont répertoriées depuis le début du XXe siècle, et avaient au XIVe siècle déjà, occasionné d’importants mouvements démographiques vers le centre et le sud.

Cela n’a donc rien à voir avec le changement (ou réchauffement selon), climatique, pourquoi ne le signalez vous pas ?

Fair point. Ghana has experienced a 1C increase in temperature since 1960 (https://www.climatelinks.org/resources/ghana-climate-change-vulnerability-and-adaptation-assessment).

Flooding affects approximately “45,000 Ghanaians every year, and half of Ghana’s coastline is vulnerable to erosion and flooding as a result of sea-level rise”. (https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/11/01/ghana-can-turn-climate-challenges-into-opportunities-for-resilient-and-sustainable-growth-says-new-world-bank-group-report).

I think that helps answer the question you raised. Ghana at least is seeing the effects of climate change quite clearly in the past 65 years. It is evidently not the case that there is ‘nothing to see with climate change’ as you state.

Pardon Mr. Demol, I did not understand Mr. Rasmus paper in the way that extreme weathers have never occurred in those countries. It talks about more and starker extreme weather’s. Why do you insinuate the paper talking about the absence of extreme weathers?

D’abord, Monsieur Kellner, de très nombreuses études démontrent que les phénomènes météorologiques extrêmes, ne sont pas plus nombreux ni plus forts, ils se remarquent plus, non seulement via les médias toujours en quête de catastrophes pour faire leur une, mais aussi et surtout, par l’urbanisation progressive de régions à risque (cyclones, inondations, séismes, sécheresses, etc.)

Et je dis que ces phénomènes extrême ne sont pas nouveaux dans ces régions (et ailleurs dans le monde), ce que l’article ne signale pas, laissant comme seule cause que le “réchauffement”, le “changement”, le “dérèglement”, climatique.

If I understand you correctly, you are saying that extreme weather events are nothing new and that it is wrong to blame them on global warming or climate change.

However, what is surely new is that the average temperature in Ghana has risen 1C since 1960, and that sea level has risen by 10-15 cm round the world (I don’t have the figure specifically for Ghana).

These are new changes, and these changes are due to climate change.

These changes tend to make extreme weather events affecting Ghana more likely.

Therefore, climate change has made extreme weather events affecting Ghana more likely.

This seems to me, to be the unavoidable logic of the situation. I had always thought that French people were very good at following logical lines of argument. It seems that I was mistaken in that belief.

Personne ne cache qu’il y avait des événements extrèmes (sécheresses et inondations) dans le passé.

Le problème est que à cause du changement climatique, la fréquence et sévérité de ses èvénements augmente successivement, que déja aujourd’hui affecte le développement de ces pays négativement.

M. Demol,

Vous parlez d’événements météorologiques. Pourquoi le docteur Rasmus en parlerait-il ? Vivez-vous dans un monde sans changements climatiques ? Je vis dans un monde où la cryosphère est en crise, caractérisée par des précipitations exceptionnelles et où nous avons enregistré les températures les plus élevées jamais enregistrées.

Nous devons réduire nos émissions de carbone, fin, point final, rien de plus.

Oui, je parle bien de faits météorologiques : l’article fait bien état de “précipitations abondantes”, de “sécheresses” et “d’inondations”. Je suis peut-être idiot en la matière, mais pour moi, il s’agit de phénomènes extrêmes issus de conditions météorologiques extrêmes, non ? Et l’article est dirigé pour faire en sorte que ce soit les “changement” ou selon, le “réchauffement” climatique la seule cause de ces phénomènes, alors qu’ils ne sont pas sans précédents, et en remontant loin même !

Et réduire nos émissions de carbone (CO2 je suppose), va servir à quoi ? Pour moi, une diminution du taux de concentration atmosphérique de CO2 ne peut qu’amener la fin du reverdissement de la planète, et les conséquences de ce phénomène.

J’attends, comme de nombreux autres, scientifiques ou simplement intéressés par le climat, que l’on m’explique clairement, dans le détail, avec des preuves observationnelles, et non des scénarios et autres modélisations informatiques, comment un petit gaz trace (CO2), peut faire augmenter la température moyenne globale, et être le “bouton de commande” du climat mondial ???

Ensuite, il y a l’ineptie du “CO2 anthropique” : Selon les chiffres officiels de divers organismes, notre atmosphère est composée principalement d’environ 78 % d’azote, 21 % d’oxygène, et 0,93 % d’argon. premier constat : il ne reste pas beaucoup de place pour les gaz dit “à effet de serre”

Ensuite : Selon ces chiffres, les activités humaines émettent environ 37,4 Gt de CO2 par an.

Les émissions naturelles elles, sont de 770 Gt/an, soit 19 FOIS PLUS environ !

Le poids total du CO2 dans l’atmosphère serait de 3.250 Gt, dans une atmosphère estimée à 5.150.000Gt …Et dans tout cela, la vapeur d’eau (H2O) est de loin le plus répandu et le plus puissant, estimé entre 0,5 et 4 % selon les latitudes, alors que le CO2 ne représente que 420 ppm environ, soit 0,042 % de l’atmosphère !

Et enfin, dans le système dit “alarmiste”, on ne voit nulle part le réchauffement naturel lié à la période interglaciaire dans laquelle nous sommes toujours, avec des variations (Optimum Romain, Optimum Médiéval, Petit Âge Glaciaire, “hiatus”) et la reprise du réchauffement vers 1800

Personne n’explique chez les alarmistes, que la capacité du CO2 à “piéger” la chaleur, est limitée, qu’après 300 ppm, le CO2 a atteint plus de 90 % de son potentiel car il est saturé.

Et ce n’est pas moi qui le dit, mais des scientifiques, des physiciens atmosphériques, comme Richard Lindzen ou William Happer.

Jean-Pierre Demol comes out with every piece of denialist nonsense known then says “And it’s not me who says this, but scientists, atmospheric physicists, like Richard Lindzen and William Happer.” These people are in the minority and include eccentrics, or cranks, and people with with ties to the fossil fuels industry. All their claims are false and have been debunked many times. Refer to skepticalscience.com.

https://skepticalscience.com/

Over 90% of climate scientists agree humans are causing all or a large part of the recent global warming according to numerous polling studies:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_consensus_on_climate_change

In addition numerous credible studies show that extreme weather events including heatwaves and heavy rainfall events and other events have become more intense or frequent or both, in recent decades. Refer to the IPCC reports that survey all the scientific literature. These reports are produced by large groups of experts. They look at what studies have the highest credibility and quality.

https://www.ipcc.ch/reports/

Monsieur Nigelj, je vous cite : Lindzen et Happer sont des excentriques, et bien sûr, argument bidon habituel, “liés à l’industrie des combustibles fossiles. Et bien par mi ces “minoritaires”, il y a encore ces études :

Il existe plusieurs études OBSERVATIONNELLES qui remettent en question l’affirmation selon laquelle les événements météorologiques extrêmes augmentent en nombre et en intensité à cause du réchauffement climatique. Voici quelques-unes des principales analyses basées sur des observations et des données historiques :

1. Ouragans et cyclones tropicaux

Philip Klotzbach et al. (2022, 2023) – Analyses des données globales des ouragans montrent une absence de tendance à l’augmentation du nombre total des cyclones tropicaux depuis plus de 100 ans.

Roger Pielke Jr. (2022) – A montré qu’en corrigeant les dommages causés par les ouragans en fonction de l’évolution des infrastructures et de la richesse, il n’y a pas de tendance significative à l’augmentation des dégâts dus aux ouragans aux États-Unis depuis 1900.

National Hurricane Center (NOAA, 2023) qui ne peut pas être qualifié de climato sceptique ou réaliste– Confirme que le nombre total d’ouragans majeurs dans l’Atlantique ne montre aucune augmentation statistiquement significative depuis plus d’un siècle.

2. Tornades

NOAA Storm Prediction Center (2023) – Les tornades les plus intenses (F3-F5) ont diminué aux États-Unis depuis les années 1970, malgré une augmentation du nombre total de tornades recensées, due à une meilleure détection avec les radars Doppler.

Brooks et al. (2014) – Étude confirmant une absence de tendance significative à la hausse des tornades violentes depuis 1950.

3. Vagues de chaleur

Freitas et al. (2017) – Étude sur les températures extrêmes au Brésil qui n’a pas trouvé de tendance significative à l’augmentation des vagues de chaleur sur le long terme.

L’étude de Black et al. (2023) – A montré que les canicules enregistrées en Europe au XIXᵉ siècle étaient aussi intenses que certaines des vagues de chaleur récentes.

4. Précipitations extrêmes et inondations

IPCC AR6 (2021) – Même le GIEC reconnaît dans son rapport que les tendances observées des inondations ne montrent pas d’augmentation claire et généralisée à l’échelle mondiale.

Hodgkins et al. (2017) – Étude sur les tendances des crues aux États-Unis et en Europe, montrant aucune augmentation significative des inondations sur le long terme.

Do et al. (2017) – Étude sur les précipitations extrêmes en Asie qui a révélé une variabilité naturelle prédominante sur les tendances à long terme.

5. Incendies de forêt

Doerr & Santín (2016) – Ont analysé les données globales sur les feux de forêt et ont constaté que la superficie brûlée au niveau mondial a diminué au cours des dernières décennies, notamment grâce à de meilleures politiques de gestion des forêts.

Abatzoglou et al. (2018) – Confirme que l’augmentation des incendies en Californie est davantage due à des facteurs anthropiques comme la mauvaise gestion des forêts et l’urbanisation en zones à risque.

Conclusion

Ces travaux observationnels montrent que les événements météorologiques extrêmes ne suivent pas une tendance généralisée à l’augmentation en fréquence ou en intensité. Si certaines zones connaissent des variations, elles sont souvent attribuables à des cycles naturels (El Niño, AMO, etc.) ou à des facteurs locaux (urbanisation, mauvaise gestion des sols).

Jean Pierre Demol

Regarding your study that finds the total number of hurricanes has not increased globally. This is correct as far as I know, but studies show that the number of category four and five hurricanes in the Atlantic have increased considerably, and that hurricanes are tending to now stall over land leading to huge levels of precipitation. This is creating huge problems.

Regarding the study showing numbers of tornadoes has not increased. Climate models EXPECT there will be no increase in the number of tornadoes.

Regarding your example finding no increase in heatwaves in Brazil. This is not representative of the entire planet (approx. 200 countries) so does not invalidate the IPCC finding that heatwaves have increased globally AS A WHOLE. Your example is misleading and its cherry picking. There may be local factors related to the Amazon that have lead to no increase in heatwaves.

Regarding your claim there is no increase in flooding (eg of rivers) . It’s very difficult to determine underlying trends in flooding, because increases in flooding get masked by flood protection improving. However there is good OBSERVATIONAL evidence globally of an increase in heavy rainfall events that often form the basis of flooding. (IPCC Reports). And it is only going to get a lot worse if we do nothing to fix the climate problem. Providing flood protection to try to counter this is already expensive and is going to get VERY expensive.

Désolé, mais vos propos sont inutiles : comme l’a dit M. Nigel, il s’agit d’un résumé d’arguments stéréotypés. Sa référence à “Skeptical Science” est tout à fait pertinente : elle existe précisément pour expliquer ces choses.

Je dirais qu’il est vrai que « les phénomènes extrêmes découlent de conditions météorologiques extrêmes », mais les « conditions météorologiques » elles-mêmes découlent du forçage climatique, notamment de l’augmentation de 50 % des émissions de CO2, ce qui est très significatif. Nous savons pertinemment que cette augmentation est entièrement due aux activités humaines, car près de la moitié de nos émissions ne restent pas dans l’atmosphère. Une augmentation des émissions de CO2 due aux émissions naturelles ne peut jamais produire un tel résultat.

Monsieur McKinney, la réponse que j’ai faite à Monsieur Nigelj, est valable pour vous également. En ce qui concerne votre commentaire à propos du CO2, je peux aussi vous répondre ceci :

Il y a des bases physiques de l’absorption du CO2 : la saturation spectrale du CO2 repose sur les principes de l’absorption du rayonnement IR selon la loi de Beer-Lambert : dès qu’une bande d’absorption atteint un niveau d’opacité élevé dans l’atmosphère, ajouter plus de CO2 a un effet décroissant sur l’absorption additionnelle du rayonnement. Et de très nombreuses études en parlent, même Arrhenius, présenté comme un des père de “l’effet de serre”, avait posé l’équation qui décrit l’effet logarithmique de l’augmentation du CO2 sur l’effet thermique dit erronément “de serre”.

En 1900 déjà, puisque souvent les chercheur de cette époque servent de référence pour l’EDS, Knut Ângström, expérimentait en laboratoire que l’absorption des rayonnements IR par le CO2 tendait vers la saturation à partir de concentrations faibles.

En 1906, Schwarzschild, avec des travaux en spectroscopie, montrait que les principales bandes d’absorption du CO2, notamment autour de 15 µ, sont déjà quasi saturées à des concentrations à partir de 200 ppm.

Au passage, il y avait le physicien Robert W. Wood, qui avait obligé Arrhenius à revoir et corriger ses calculs, et qui vers 1909, avait démontré que l’effet dans une boite en verre, comme une serre, était dû à la convection et non à l’absorption d’IR.

Entre 1956 et 1959, Gilbert N. Plass, avait confirmé dans ses études sur le rôle du CO2 dans l’absorption atmosphérique, une saturation dans certaines bandes spectrales.

Et enfin, il y a les études plus récentes, comme les données satellitaires et les mesures atmosphériques “HITRAN Database, dont les simulations montrent que la bande principale du CO2 est effectivement saturée.

Ou encore, les expérience en laboratoire et les mesures des satellites NIMBUS4, AIRS, IASI, etc, qui confirment l’évolution logarithmique du CO2 avec sa concentration.

Il y a aussi les données spectroscopiques atmosphériques MOTRAN, qui confirment que l’absorption principale du CO2 était déjà saturée avant l’ère industrielle, lorsque la teneur en CO2 était de 280 ppm.

Ensuite il y a les études des scientifiques que les “alarmistes” n’aiment pas : Lindzen, Happer, van Wijngaarden, Gerlich, Tsceuschner, Geuskens, Clauser, Marko, Mullis, Shaviv, Singer, Soon, Vaughan, Spencer, Christy, Berkhout, Masson, Van Vliet, Corbyn, Courtney, Easterbrook, Gervais, Giaver, Préat, Humlum, Prodi, Curry, et quelques milliers d’autres “minoritaires”, “excentriques” et bien sûr tous, liés à l’industrie de combustibles fossiles …

“It is urgent to start climate change adaptation because of the rapid global warming (e.g. “pulse.climate.copernicus.eu) and global statistics show that temperature and rainfall have already become more extreme. Also, climate change adaptation may send a message of the urgency and importance for mitigation.”

It’s important to point out that both mitigations and adaptation as well as improving infrastructure are similar to installing renewables. Very little of it can be done without using vehicles that run on gasolines and renewable biofuels. What that obviously means is more oil will be needed and used to finish the job. That also means that atmospheric CO2 will continue to rise at least until significant adaptations and renewables are in place. The future is all about transportation.

AI says that the regreening of the Sahara could be kicked off by global warming. Fact or hallucination?