Guest commentary by Michael Tobis

This is a deep dive into the form and substance of Michael Shellenberger’s promotion for his new book “Apocalypse Never”. Shorter version? It should be read as a sales pitch to a certain demographic rather than a genuine apology.

Michael Shellenberger appears to have a talent for self-promotion. His book, provocatively entitled “Apocalypse Never” appears to be garnering considerable attention. What does he mean by that title? Does it mean we should do whatever we can to avoid an apocalypse? Does it mean that no apocalypse is possible in the foreseeable future? For those of us who haven’t yet read the book (now available on Kindle), Shellenberger provides an unusual article (at first posted on Forbes, then at Quillette and the front page of the Australian) which appears less a summary than a sales pitch, an “op-ad” as one Twitter wag put it.

It’s called “On Behalf Of Environmentalists, I Apologize For The Climate Scare”. In short, Shellenberger lands clearly on the naysayer soil. Not much to see, everyone. Cheer up, carry on, these are not the droids you’re looking for.

FEW PEOPLE KNOW THAT THE MOON IS MADE OF CHEESE

In support of this insouciance, Shellenberger offers twelve “facts few people know”. Most of the points are defensible to some extent, and most of them raise interesting topics. A main purpose of this article is to provide references to the relevant discussions. But in going through it, it’s worth keeping an eye on the rhetorical purposes of the items, which appear a bit scattershot, and to the rhetorical purpose of the list, which might appear rather obscure.

Clearly labeling the list “facts that few people know” implies that all these points unambiguously refute common beliefs that are widely. And the “apology for the climate scare” indicates further that these beliefs are widely held by a supposedly misguided community of “climate scared”. A defender of the list, Blair King suggests that “[Shellenberger] identified false talking points used repeatedly by alarmists to misinform the public and move debate away from one that is evidence-based to one driven by fear and misinformation”. That does seem to be a fair reading of the stated intent of the list, but it just doesn’t ring true as a whole.

Speaking as a verteran “climate scared” person, the items don’t seem especially familiar. It’s hard to imagine a conversation like this:“Gosh, climate change is an even bigger threat to species than habitat loss.”“I know, and the land area used for producing meat is increasing!”As Gerardo Ceballos said:

This is not a scientific paper. It is intended, I guess, to be an article for the general public. Unfortunately, it is neither. It does not have a logical structure that allows the reader to understand what he would like to address, aside from a very general and misleading idea that environmentalists and climate scientists have been alarmist in relation to climate change. He lists a series of eclectic environmental problems like the Sixth Mass Extinction, green energy, and climate disruption. And without any data nor any proof, he discredits the idea that those are human-caused, severe environmental problems. He just mentions loose ideas about why he is right and the rest of the scientists, environmentalists, and general public are wrong.

What causes the strange incoherence of these “facts few people know”? At the end of this review I’ll propose an answer. Meanwhile, I will consider several questions regarding each item:

- VALIDITY Is the claim unambiguously true? Unambiguously false? Disputed?

- RELEVANCE TO CLIMATE Is the claim directly relevant to climate concern/”climate scare” or is it more of interest to tangentially related environmental issues?

- SALIENCE Is the contrary of the claim widely believed by environmental activists? Does widespread belief in the claim contribute materially to an excess of climate concern?

- IMPLICATION What is the rhetorical purpose of the question?

- REALITY To what extent is the rhetorical purpose justified?

THE TWELVE POINTS

1) Humans are not causing a “sixth mass extinction”

In a literal sense this claim has its defenders. See “Earth is Not In the Middle of a Sixth Mass Extinction”. The article quotes Smithsonian paleontologist Doug Erwin, who wrote to me in an email:.

Many of those making facile comparisons between the current situation and past mass extinctions don’t have a clue about the difference in the nature of the data, much less how truly awful the mass extinctions recorded in the marine fossil record actually were.

It is absolutely critical to recognize that I am NOT claiming that humans haven’t done great damage to marine and terrestrial [ecosystems], nor that many extinctions have not occurred and more will certainly occur in the near future. But I do think that as scientists we have a responsibility to be accurate about such comparisons…

I think that if we keep things up long enough, we’ll get to a mass extinction, but we’re not in a mass extinction yet, and I think that’s an optimistic discovery because that means we actually have time to avoid Armageddon

I leave it to the reader as to whether “not in a mass extinction yet” is reassuring. While there are several possible understandings of “mass extinction”, it’s generally agreed that we are indeed losing species at a rapid rate. Erwin is pointing out that the vast majority of life isn’t collapsing, that we aren’t collapsing into a nearly lifeless planet “Yet.” Will people reading Shellenberger’s quote get the message “we’re not in a mass extinction yet, … we actually have time to avoid Armageddon”? I venture that if they read about it in a book called “Apocalypse Never” they won’t. Is this related to something we might call “The Climate Scare”? Not yet. Climate is only a secondary feature of species loss so far, although there are plenty of signs of a climate impact in what’s left of natural ecosystems.

- VALIDITY – Valid only provisionally and somewhat of a semantic quibble.

- RELEVANCE TO CLIMATE – Speculative; if we don’t get a handle on climate change, climate change will make it worse.

- SALIENCE – This one is genuinely scary, so it’s okay to be scared about it.

- IMPLICATION – You are presumably meant to read this claim as “This talk about a sixth extinction is typical climate alarmist scaremongering”

- REALITY – We are not literally in a mass extinction event yet but we are on the brink of one. It’s not really a “climate scare” topic but it’s related, and enormous. It seems utterly bizarre for someone claiming to speak “on behalf of environmentalists” to minimise it.

2) The Amazon is not “the lungs of the world”

It’s fair to say that “the Amazon is the lungs of the world” is an environmentalist talking point. It’s fair, I think, to say that some members of the public are afraid of killing enough trees that we run out of oxygen (never mind that lungs consume oxygen rather than producing it!). It turns out that what maintains the oxygen fraction in the atmosphere is a rather interesting question, but that there is no immediate risk of the oxygen going away. Here’s a paper (w/thanks to Chris Colose).

We have built up an enormous stockpile of the stuff. If we live long enough that the oxygen concentration changes appreciably, we will have survived the current century and many centuries to come. Is it a reason to NOT preserve the Amazon? Hardly. The Amazon is the repository for much of the land surface biodiversity. A better analogy would be that it’s more like our planetary gut than our planetary lungs. It would be stupid beyond belief to injure it, yet injure it we do. Does the fear of disappearing oxygen feed excessive “environmentalist” panic? Arguably so among the more excitable members of the general public sharing half-baked ideas on social media. But is it part of “The Climate Scare”? It’s a bit of a stretch. One could point out, though, that totally clearing the Amazon would have direct impacts on climate, according to several modeling studies, for instance.

- VALIDITY – The claim is meaningless, so the counterclaim is meaningless

- RELEVANCE – It’s a pretty muddled belief, but it could conceivably be seen as climate related.

- SALIENCE – In fact there is baseless alarm about the Amazon’s ability to provide oxygen

- IMPLICATION – “Don’t lose sleep about the Amazon; it’s not important.”

- REALITY – The Amazon is the repository of an enormous amount of biodiversity that is at risk. Truly destroying it entirely would have climate impacts. Saving it is an important issue. But not because of oxygen!

3) Climate change is not making natural disasters worse

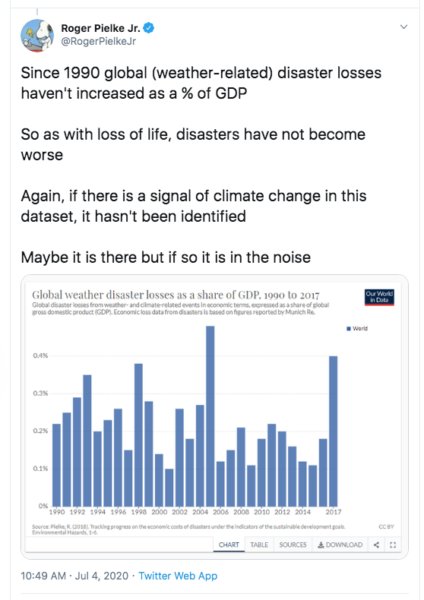

Roger Pielke Jr. enters the fray. This claim is obviously based on his position which Roger helpfully summarizes in a recent Twitter thread

First, what is a disaster?

— The Honest Broker (@RogerPielkeJr) July 4, 2020

A disaster refers to impacts

By themselves, eg, an earthquake or hurricane is not a disaster

For humans we typically measure impacts in lives lost or economic losses (obviously there are other metrics)

This is the definition of the IPCC pic.twitter.com/OnsllRj07H

This is a very specific definition of “disaster” which Roger defends vigourously. One suspects that he does so precisely because the signal is buried in the noise in his definition. It’s a definition that could hardly have been better designed to avoid statistical significance!

I wrote more about that here. Take note: Pielke only claims “there is no statistical evidence that disasters are getting worse” while Shellenberger states “disasters are not getting worse”. A classic conflation of “absence of evidence” with “evidence of absence”. In addition, Pielke’s claim only stands because the rising costs of disasters have been normalized by the rise in GDP. It is entirely unclear why this is the relevant metric. Shellenberger’s claim, despite Pielke’s defense of it, is not defensible by reference to Pielke.

- VALIDITY: Shellenberger’s claim goes too far even based on Pielke’s significance-averse approach.

- RELEVANCE: relevant to climate change impact

- SALIENCE: Yes, people do worry about it a lot. Perhaps a bit too soon, but it’s not an unrealistic concern.

- IMPLICATION: “No sign of a problem!”

- REALITY: There are many signs that several types of severe events (notably heatwaves, drought impacts, and intense precipitation) are becoming more common and more severe.

4) Fires have declined 25 percent around the world since 2003

After the nitpicking of points 1 and 3, it’s very interesting to see the fuzziness here. It is true that total annual area burned worldwide has declined. But this is because grass fires have declined, because of increasing human appropriation of grasslands for agriculture. Forest fires, which are more ecologically damaging than grass fires, have increased.

While NASA’s new video does show regional upticks in certain parts of the world, scientists made clear that the total number of square kilometers burned globally each year has dropped roughly 25 percent since 2003. This has largely been due to population growth and development in grasslands and savannas, as well as to an increase in the use of machines to clear farmland. “There are really two separate trends,” said James Randerson, a scientist at the University of California, Irvine who worked on the new wildfire video. “Even as the global burned area number has declined because of what is happening in savannas, we are seeing a significant increase in the intensity and reach of fires in the western United States because of climate change.”

So, areas and intensity of forest fires have increased, and this claim is simply misdirection by mixing two phenomena, increasing forest fires and increasing human footprint on grasslands. The concern about increases in forest fires is valid.

- VALIDITY: Misleading. Conflates two anthropogenic phenomena into one.

- RELEVANCE: relevant to climate change impact

- SALIENCE: Yes, people do worry about it a lot. Justifiably.

- IMPLICATION: “See? Climate activists are deluded about wildfires.”

- REALITY: Forest fires do appear to be increasing in frequency and severity. This is unsurprising as forests are exposed to warmer conditions that the ones for which they evolved, so are more prone to drying out.

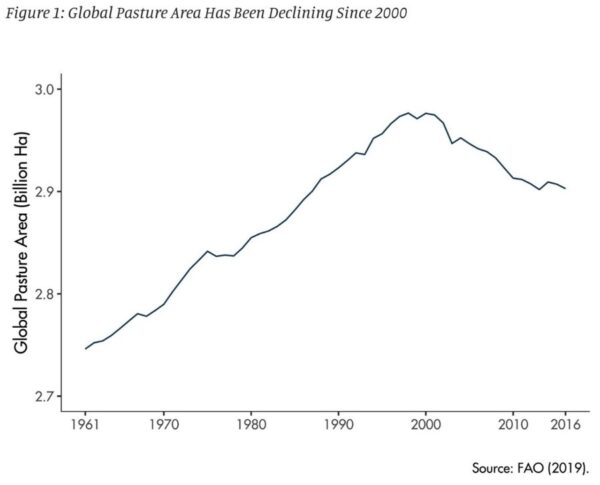

5) The amount of land we use for meat—humankind’s biggest use of land—has declined by an area nearly as large as Alaska

This turns out to be a defensible claim. But it’s not such a happy result. “this contraction is mostly in arid regions where scrubland was used for extensive low impact grazing. Some of the declines in these regions have been offset by expansions of grazing in tropical regions where the environmental destruction is immense e.g. in the Amazon. This “livestock revolution” has come with consequences associated with the spreading of fertilizers, and the draining of ecologically sensitive wetlands.” Regardless, as a careful examination of the vertical axis on the graph shows, on a percentage basis it’s small.

Finally, from personal experience I would point out that. at least in central Texas, much pasture land has been abandoned because it was ruined by overgrazing. I expect it’s similar elsewhere. Returning denuded limestone to “nature” is not that great of a gift.

- VALIDITY: Marginal. Made out as an important trend when it’s really not.

- RELEVANCE: No obvious relevance to climate.

- SALIENCE: I don’t think this is a prominent concern among environmentalists at large.

- IMPLICATION: ??? (It’s unclear what purported “alarmist idea” this counters.)

- REALITY: The impacts of meat production are elsewhere.

6) The build-up of wood fuel and more houses near forests, not climate change, explain why there are more, and more dangerous, fires in Australia and California

It’s undisputed that fire suppression has built up fuel in many places, and that people have built housing in dangerously fire-prone locations. It’s also undisputed that the recent fires in Australia, as well as spectacular events in Russia in 2010 and Texas in 2011, occurred in conditions of literally unprecedented heat and drought. Of course, fires happen in hot dry years. But we’re seeing an obvious trend in such outliers. Things can have more than one cause.

- VALIDITY: As stated, literally false. Things can have more than one contributing factor.

- RELEVANCE: climate impact relevant

- SALIENCE: People worry about this, and they should

- IMPLICATION: “Hot weather doesn’t make forests burn because fire suppression makes forest burn, so don’t worry about climate change!”

- REALITY: Unsurprisingly, forests are more likely to dry out and burn when it’s hotter.

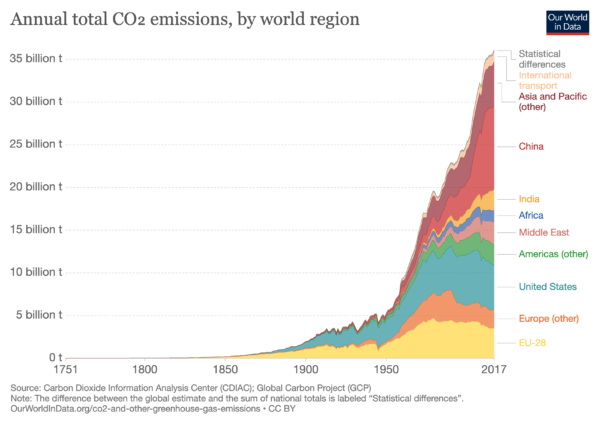

7) Carbon emissions are declining in most rich nations and have been declining in Britain, Germany, and France since the mid-1970s

This is true. In some countries it is quite substantial. It has two primary causes: 1) Recent declines in coal consumption, mostly replaced by natural gas. Since climate stability is only achieved at net zero emissions, investment in gas infrastructure is a mixed blessing. 2) Much industrial activity moving to Asia, especially China. This is just moving the problem, not solving it. It’s “global warming”, not “national warming”. If you look at the global trajectory rather than that of individual countries, emissions continue to burgeon. Even the recent pandemic related events appear so far to have been very temporary. If you compare what is happening now to the path required to limit warming to any particular target, especially 2ºC or better, it’s very hard to take this little bit of good news with too much jubilation.

Sam Bliss points out that no rich country is reducing emissions fast enough to keep global warming under 2ºC — or even planning to.

No rich country is reducing emissions fast enough to keep global warming under 2C — or even planning to. The UK and Sweden have committed to reduction pathways that entail twice their fair share of carbon emissions, according to @KevinClimate et al. https://t.co/BEAEtf1GN6

— Sam Bliss (@ii_sambliss) July 2, 2020

- VALIDITY: True, but something of a cherry pick

- RELEVANCE: climate relevant, but the narrow claim is nowhere near as important as is implied

- SALIENCE: I don’t know that people are worried about small declines in emissions records of particular countries. People are certainly worried about global totals, though.

- IMPLICATION: “We’re already fixing the problem! Relax!”

- REALITY: We are still very far from fixing the problem, and the hard-won but modest progress in a few wealthy countries is not reassuring.

8) “The Netherlands became rich, not poor while adapting to life below sea level”

First, we should probably neglect point 8 altogether, since it is commonly known that the Dutch have done well over the centuries, and that they have won back a fair piece of land from their continental shelf. So it doesn’t qualify as something “few people know”. It’s sloppy to include it on the list.

Clearly the implication that “alarmists say the Dutch are not wealthy!” is just nonsense. What about “alarmists say the Dutch are drowning”? I’ve not heard that one either. So logically speaking we can ignore this point. Is this merely silly? Can Shellenberger be claiming that bad news is good news? That we should embrace climate change because it will build character? Is this the quality of argument that we’re facing?

Let’s bend over backwards to consider the matter. It appears that the point is that at least one society has adapted to life below sea level; so we all can do that. But does that really mean that the Dutch are prepared to adapt to sea level rise of meters? There are two approaches to thinking about the Dutch situation in the future. Some are bravely advocating a “make lemonade” approach, inclining toward the insouciant “disasters are business opportunities” framing that Shellenberger implies. But others which look in deeper detail are more sobering:

Of course, dikes are being raised, and rivers given some room to overflow occasionally, but will that be enough? And more importantly: how long will it last? Sea levels have only just started to rise, and it may be going faster than we had initially thought. The big question is: will the Netherlands as we know it survive what’s coming?

In order to keep the seawater at bay, the dikes will need to be raised. As a result, the polders behind them will become relatively deeper, making them more vulnerable and more expensive to maintain. These higher dikes are also a problem in themselves: they prevent natural silting, which means our delta is unable to grow along with the advancing sea.

The experts share one concern: the Netherlands has no Plan B for a scenario in which sea levels rise faster than are accounted for in the Delta Programme. At the same time, there is no proper public debate about this issue, despite the urgent need for one. Not sometime in the future, but right now – because we need to make some important choices today. Especially if you consider how long it takes to develop and implement plans.

Reducing CO<sub>2</sub> emissions and reinforcing dikes is only half the story. The other stark reality is that even these measures combined may prove insufficient in the long term to preserve the lower-lying parts of our country. The polder model – in its literal rather than political sense – has its limits, some physical and some more subjective. The physical limits are based on hard science: how quickly will sea levels rise – and how much can we actually handle? The subjective limits are a question of taste: what kind of country do we want to live in (while we still have time to decide)?

Can we adapt to sea level rise? The implication of this point is that we can adapt like the Dutch. But can the Dutch, who are the world’s experts on managing land below sea level adapt? Only, it appears, within limits.

- VALIDITY: Undisputed. Indeed, hard to imagine why this qualifies as a “fact few people know”!

- RELEVANCE: relates indirectly to climate impacts

- SALIENCE: People do worry about sea level rise, and they should

- IMPLICATION: “Sea level rise is harmless since humans can rise to the occasion of great challenges.”

- REALITY: Even the Dutch, wealthy and experienced in managing coastal flooding, are very worried.

9) We produce 25 percent more food than we need and food surpluses will continue to rise as the world gets hotter

This is a bit controversial, but I think Shelleberger is correct. Large scale agriculture can adapt to changing conditions. Crop failures in one place or another may become more frequent as climate becomes less predictable and in some ways more severe, but global production will probably remain adequate for a long time, provided the current economic and trade regime remains healthy. A survey article is here. The impacts of climate change on food supply, except on the poorest, is expected to be relatively modest, compared to other scenario variables:

Finally, all quantitative assessments we reviewed show that the first decades of the 21st century are expected to see low impacts of climate change, but also lower overall incomes and still a higher dependence on agriculture. During these first decades, the biophysical changes as such will be less pronounced but climate change will affect those particularly adversely that are still more dependent on agriculture and have lower overall incomes to cope with the impacts of climate change. By contrast, the second half of the century is expected to bring more severe biophysical impacts but also a greater ability to cope with them. The underlying assumption is that the general transition in the income formation away from agriculture toward nonagriculture will be successful.

How strong the impacts of climate change will be felt over all decades will crucially depend on the future policy environment for the poor. Freer trade can help to improve access to international supplies; investments in transportation and communication infrastructure will help provide secure and timely local deliveries; irrigation, a promotion of sustainable agricultural practices, and continued technological progress can play a crucial role in providing steady local and international supplies under climate change.

This said, climate change will have an enormous impact on traditional food-gathering and subsistence agriculture. Traditional methods will fail. Greenland is a harbinger. If traditional cultures and folkways are valuable, their food gathering and subsistence methods are central. These are being lost.

- VALIDITY: Plausible

- RELEVANCE: relevant to climate change

- SALIENCE: I think there is a strong case that there’s too much public alarm on the climate- food security axis.

- IMPLICATION: “Food is not a big climate issue!”

- REALITY: If the international economic order holds together, enough nutrients to feed everyone will be produced in the foreseeable future. But climate change impacts on traditional cultures are already severe and will likely eventually be overwhelming. Distributional issues may leave people hungry even as enough food is produced in aggregate.

10) Habitat loss and the direct killing of wild animals are bigger threats to species than climate change

It’s not clear how to formally evaluate this claim. It is surely true of some species and not of others. Coral reef species, for example, are under direct threat from ocean acidification and local warming events. Habitat loss can certainly be exacerbated by climate change. Here, the recent example of Australian fires is instructive. These phenomena can’t be directly separated. Climate change causes habitat loss.

The main way in which climate stress affects natural species is through habitat loss via climate niche moves and disappearance. It isn’t at all clear that the comparison between habitat loss and climate stress, even if it were possible, would be very informative. You can’t really protect wildlife without protecting or creating stable habitat. Under rapid climate change that becomes impossible.

- VALIDITY: The assertion is overly broad and probably untestable.

- RELEVANCE: climate relevant

- SALIENCE: People do worry about habitat and people do worry about climate; sometimes they get them confused, and sometimes they are related. It’s not clear concerns are excessive

- IMPLICATION: “Climate change is not a problem for wildlife!”

- REALITY: Climate change is a major driver of habitat loss, so if you care about habitat, you should care about climate policy.

11) Wood fuel is far worse for people and wildlife than fossil fuels

This conflates several issues.

- Wood-burning ovens and grills in wealthy countries are a carbon neutral luxury of no great biogeochemical importance. There is no controversy on this matter that I know of.

- Biofuels are carbon neutral. Although it is a relatively minor source of energy, extracting energy from burning wood waste is better than simply letting the waste decay, producing the same CO2 without capturing the energy. However, mis-designed carbon credit systems in Europe have been encouraging growing trees specifically for the purpose of burning them. While carbon-neutral in the long run, this use produces carbon in the short run and consumes it on a longer time scale, front-loading emissions. It is a carbon-overshoot strategy, and there’s a strong case to be made that given our present trajectory toward exceeding global warming targets, it’s a bad idea. However, on this matter, one would tend to see the most “climate alarmed” as aligned with Shellenberger, not opposed, so it doesn’t support his case.

- Wood-burning for home cooking in less developed countries is a real health issue. This is certainly true, but no important group is advocating household wood fuel as a mainstay for large populations that I know about. It’s possible to imagine an innumerate anti-technology Luddite advocating returning to wood-burning stoves, but it’s difficult to imagine that gaining much purchase, insofar as forests are greatly valued, if not even overvalued, by climate activists. So on these points, Shellenberger is probably better aligned with “climate activists” than against them.

- VALIDITY: The claim is true, especially insofar as low-technology wood-burning is concerned.

- RELEVANCE: Not first order climate relevant. Nobody is proposing replacing fossil fuels with wood burning on a global scale.

- SALIENCE: The biofuel issue is a real controversy and second order relevant to the climate problem, but modern biofuel plants not a major health concern, certainly compared to coal plants. The use of wood-burning in households is a real health issue, but not climate relevant. Shellenberger is probably better aligned here with “climate activists” than against them.

- IMPLICATION: Hard to know. Maybe “the environmental crazies want to take away your furnace and put a nasty sooty wood-burning hearth in your kitchen.”

- REALITY: Poor wood burning practice in households is indeed unhealthy, but carbon neutral. The issue of biomass burning is complex; some uses are better than others. Growing wood specifically for fuel has deleterious impacts on the carbon trajectory, and is probably not a great idea, even though the strategy is basically long-term carbon neutral.

12) Preventing future pandemics requires more not less “industrial” agriculture

There seems to be a case being made that CAFOs (Confined Animal Feeding Operations) are less dangerous than pastures on this account. My initial investigations on the subject turned up a lot of evidence against Shellenberger’s claim.

I finally turned up what must be Shellenberger’s source. This piece is attributed to the young Alex Smith – Alex joined Breakthrough as a research analyst in the food and agriculture program in 2019 after completing a dual MA/MSc in International and World History from Columbia University and the London School of Economics and Political Science. In his masters, Alex studied and wrote about American foreign policy, French colonialism, and environmental history. In short, Mr Smith doesn’t seem to have much formal knowledge about pandemics or agriculture. He concludes:

With our global population set to increase by close to 3 billion by 2050, we must strive to construct a world that can provide food, shelter, and livelihoods to all 10 billion people, while reducing risk of pandemics akin to what we see today. Simply, the only way forward is forward. We must continue to develop agricultural innovations that can allow for increased intensification, and we must give these innovations global reach. It does not work to just intensify agricultural production in developed countries, given the dual role of land-use change and food insecurity. To combat the main drivers of zoonotic diseases, we must sustainably intensify our food system, not pine for a romanticized and inefficient production system that brings people and wild animals in closer contact.

Frankly, this reminds me of the Monty Python sketch that teaches you how to play the flute. Smith dismisses the obvious solution in his second paragraph:

But these claims offer no explicit argument for how a different form of agriculture — outside of calls to completely eliminate meat consumption — would reduce risk, and they often conflate intensive animal agriculture with intensive agriculture writ large.

I myself have indeed given up on animal products almost altogether (I do have a weakness for butter-based desserts at cafés that I occasionally indulge) so I can’t resist noting this dodge. I don’t see any reason meat can’t go back to being an occasional luxury as it was through most of human history. But this is hardly the place for that discussion. To the point, Shellenberger seems to be putting up basically a blog post by a young man with a history degree against the entire field of epidemiology, and declaring “a fact” on that basis. I’d call that a stretch.

- VALIDITY: The claim is very weakly supported and probably wrong.

- RELEVANCE: No obvious climate relevance

- SALIENCE: I think people do, sensibly, worry about the way meat is produced

- IMPLICATION: “Coop up animals in meat factories! It’s good for you and they don’t mind much.”

- REALITY: Er, no.

CONCLUSION

It’s very hard to imagine a significant community of people adamantly holding to the contrary of Shellenberger’s points. They really aren’t core to any particular group.So what is he up to, if it’s more than just selling a book?

Is this the problem, then? Half-truths, incoherent cases, sound-good arguments that in total don't add up to a coherent case against environmentalism except seemingly on 4-minute between-commercial segments on conservative talk radio but not in thought-out rational discourse?

— David Appell (@davidappell) July 2, 2020

I think David hits the nail on the head. It’s a pitch to denialism, not to moderation. But why is is so strangely constructed, so uncompelling to some of us, and yet apparently convincing to others? There’s a provocatively titled article at The Forward that has an answer:

The fuel for this fire comes from something that anthropologists call the myth of outgroup homogeneity. We tend to believe everyone in our tribe is nuanced and diverse, while all the members of that tribe over there are uniform and zombie-like. This is how New York thinks of New Jersey, Lakers fans think of Clippers fans, Mac users think of PC users, and MSNBC viewers think of Fox News viewers. The outgroup homogeneity effect makes it easier to blame a whole side for their crazy fringe while barely acknowledging your own. You can march under a big dumb banner, saying you’re from the smart, nuanced part of your coalition, while believing everyone on the other side has no more profound beliefs than their big, dumb banner.

Shellenberger’s weird list makes no sense at all. It certainly doesn’t bear up well under close inspection. But it makes some sense to his readers, only because they perceive the world of the climate concerned as “uniform and zombie-like”. Every single point of contention he raises is viewed through that lens first.

Is Shellenberger really even a “former environmentalist”? Has he ever actually advocated a “climate scare”? Does he have anything to apologise for? The evidence for his (oddly un-contrite) apostasy is thin. His list, baffling to those of us it is meant to accuse, holds together as an example of “outgroup homogeneity”. Shellenberger’s capacity to frame a list this way depends on a capacity to grossly oversimplify his “climate scare” opposition. His baffling caricature of his opposition would indicate that he never really was part of a “climate scare” in the first place!

The article, remember, is entitled “On Behalf Of Environmentalists, I Apologize For The Climate Scare”. I suggest Shellenberger in innocent on that score. He may however owe us a different apology.

145

Mister McKinney’s Discourse should be celebrated for exemplifying the Risks of not heeding Mr. Pope’s admonition

A little learning is a dangerous thing

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.