Everyone is talking about emissions budgets – what are they and what do they mean for your country?

Our CO2 emissions are causing global heating. If we want to stop global warming at a given temperature level, we can emit only a limited amount of CO2. That’s our emissions budget. I explained it here at RealClimate a couple of years ago:

First of all – what the heck is an “emissions budget” for CO2? Behind this concept is the fact that the amount of global warming that is reached before temperatures stabilise depends (to good approximation) on the cumulative emissions of CO2, i.e. the grand total that humanity has emitted. That is because any additional amount of CO2 in the atmosphere will remain there for a very long time (to the extent that our emissions this century will like prevent the next Ice Age due to begin 50 000 years from now). That is quite different from many atmospheric pollutants that we are used to, for example smog. When you put filters on dirty power stations, the smog will disappear. When you do this ten years later, you just have to stand the smog for a further ten years before it goes away. Not so with CO2 and global warming. If you keep emitting CO2 for another ten years, CO2 levels in the atmosphere will increase further for another ten years, and then stay higher for centuries to come. Limiting global warming to a given level (like 1.5 °C) will require more and more rapid (and thus costly) emissions reductions with every year of delay, and simply become unattainable at some point.

In her recent speech at the French National Assembly, Greta Thunberg rightly made the emissions budget her central issue.

So let’s look at how the emissions budget concept can be used to guide policy on future emissions trajectories for countries.

Step 1: The temperature goal

First we need to determine at what level we want to stop global warming. That’s quite simple because it has already been agreed in 2015 by all nations in the Paris Agreement. That has taken decades of discussion and negotiations, ever since nations agreed in 1992 at the Rio Earth Summit to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic (human induced) interference with the climate system.” In Paris a consensus was finally reached on “limiting global temperature increase to well below 2 degrees Celsius, while pursuing efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees”.

Last year, the IPCC special report Global Warming of 1.5 °C (in short SR15) detailed strong reasons for why limiting to 1.5 °C would be much more sensible than to 2 °C.

Step 2: The global CO2 budget

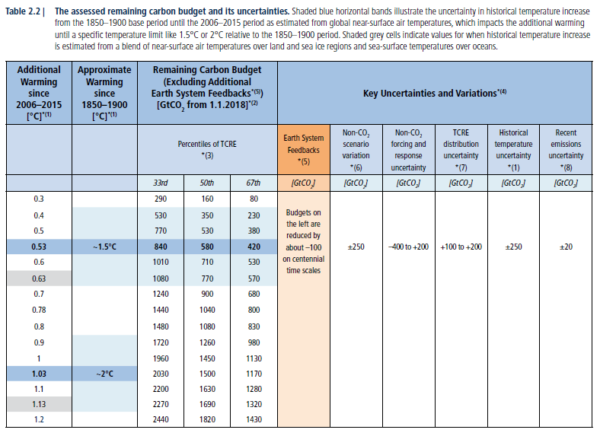

Once the temperature limit has been agreed, we need to know the corresponding CO2 budget. That is a question for science, and the IPCC SR15 answers that, including the uncertainties as always is a hallmark of good science. The following shows the budget table from IPCC.

The uncertainties to a large extent result from the fact that CO2 is the main but not the only cause of human-caused climate change, so the CO2 budget depends on how we will deal with non-CO2 climate forcings such as aerosol pollution. There are also different methodologies to estimate the CO2 budget. A thorough analysis of the uncertainties is found in a recent paper by Rogelj et al. in Nature. The bottom line, as one of the co-authors (Elmar Kriegler) told me, is that the SR15 estimates in the table above are still the best we have.

Some have argued that the uncertainties make the budget approach a poor guidance for policy. I disagree. First of all, practically all of politics operates under high levels of uncertainty about the outcome of policy decisions; that is inevitable. In fact it is rare that politics has a clear guidance like the well-established linear relationship between cumulative emissions and global temperature. Those who criticise using this as policy guidance must come up with a better guidance providing less uncertainty, then we can discuss.

Second, some of the uncertainty is captured by the probabilities for reaching a certain temperature limit, shown in the table, so society can simply decide what level of risk of overshooting a temperature level they are willing to take.

And finally, all policy is to a large extent learning by doing. You start with the best scientific advice now (especially since we cannot afford to wait any longer), and if we know more in ten years time we can adjust policy then. Given that climate change is largely irreversible it is best to err on the safe side, i.e. the uncertainty, if anything, is a reason to apply the precautionary principle and reduce emissions fast.

Greta has argued in her speech to use 67% probability for staying below 1.5 °C, i.e. a 420 Gt budget from the start of 2018. Subtract 2 years of emissions, i.e. 80 Gt, then we’re left with 340 Gt from the start of next year. That is 8.5 years of current emissions – or 17 years until zero emissions in case of a linear rampdown.

If you translate the “efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees” promised by all nations in the Paris Agreement as a policy that gives us 50:50 chance to actually achieve that goal, that’s 500 Gt from the start of next year. That’s 12.5 years of current emissions, or 25 years for a linear rampdown, i.e. halving emissions in 12.5 years to reach zero by the end of 2044.

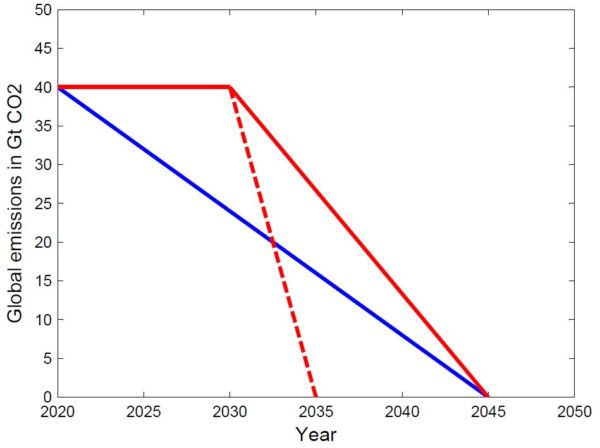

But beware of using those end dates instead of budgets, because it is not the end date but the cumulative emissions that count! A simple illustration: if you don’t achieve reductions in the next ten years but keep emissions constant, and reduce linearly after that, the result is that you have to reach zero ten years earlier! See the next figure.

This is why one should not attach much value to politicians setting targets like “zero emissions in 2050”. It is immediate actions for fast reductions which count, such as actually halving emissions by 2030. Many politicians either do not understand this – or they do not want to understand this, because it is so much simpler to promise things for the distant future rather than to act now. Greta asked the pertinent question in her Paris speech:

”What I would like to ask all of those who question our so called ‘opinions’, or think that we are extreme, is: Do you have a different budget for at least a reasonable chance of staying below a 1,5° of warming? Is there another, secret Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change?”

Step 3 Computing a budget for your country

How do you divide up the remaining budget amongst humankind? This is a crucial step since most climate policy is made at the national level. Yet, this is not a scientific question but one of climate justice. Who gets how much?

I can’t solve this question but I am going to propose a starting point, based on the idea that a principle of fair distribution needs to be universal and simple. The most simple one clearly is an equal per capita distribution. Anyone who wants more of the budget than someone else would need to provide a good reason. There could be many reasons – cold countries might claim they need more emissions for heating, hot countries for air conditioning, large countries for transport over long distances, developing countries to eradicate poverty, rich countries because they are already developed.

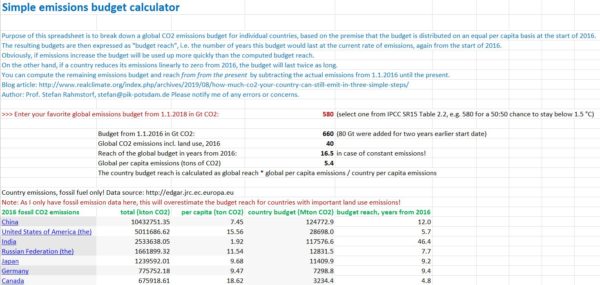

A tricky question is: at what point in time do you distribute the budget? This is important because rich countries are eating up the remaining CO2 cake much faster than poor countries. I would propose: from the time of the Paris Agreement, i.e. from the start of 2016. Of course developing nations will argue (and have argued) for a much earlier start date, to account for the historic emissions of developed nations. That may be justified but has the practical problem that the remaining budget for countries with large per-capita emissions is then already zero or rather: overdrawn.

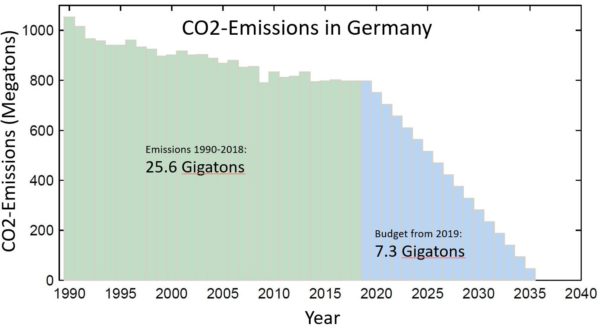

So just to be practical, let’s take 2016. So you compute the remaining global budget at the start of 2016 by adding 80 Gt to the IPCC budget table numbers shown above. Then you multiply that number by the population of your country, divide by the global population, and then subtract the emissions of your country from the start of 2016 until now. I have done this for Germany (in a German blog post) using a global budget of 800 Gt from the table, just to be generous, for a 67% chance to stay below 1.75 °C (my interpretation of “well below 2 °C”). The result was a remaining emissions budget of 7.3 Gt from the start of 2019 or 6.5 Gt from the start of 2020. That is 8 more years at current emissions. The next figure shows a linear reduction trajectory compatible with this budget.

I’m not so concerned about the exact numbers, given the uncertainties discussed above. But there are at least three important conclusions from the budget approach.

First of all, nations with high per-capita emissions need to reduce faster than others, based on the limited budget and simple justice considerations. If some reduce faster and some slower, even if every nation reduces linearly global emissions will not decline linearly, but more rapidly at first from the reductions of wealthy nations, with a longer tail of emissions from developing nations reaching zero later.

Second, even with generous assumptions (like an 800 rather than 420 Gt global budget and a 2016 start date for dividing up the cake) emissions from developed nations need to drop much faster than almost all politicians think, in order to honour the Paris agreement.

Third, it is not some end date that counts but rather very rapid reductions starting right now. The end date is a moving target – every year we wait we lose two years: the year we waited, and a year at the end because the required end year moves towards us.

Finally, unprecedented global cooperation is needed to tackle the climate crisis. This may involve deals that make the tight budgets more palatable to countries with high per-capita emissions – for example they might find partners with low emissions and negotiate to use some of their budget in exchange for technological and financial support in climate adaptation and mitigation.

p.s. (7 August): I have posted a spreadsheet where you can look at this budget estimate and the budget reach in years for any country. Someone suggested on twitter I should provide a site which automatically produces the figure above for any country – I don’t have the time to do this but it is not a bad suggestion, perhaps there is a volunteer?

References

For a more complex formula to share the budget: Raupach et al. 2014, Sharing a quota on cumulative carbon emissions.

I think it should be written “around 40 BILLION tons are emitted annually” (below the table)

[Response: Thanks, typo fixed!]

How to Power the World?

http://bravenewclimate.proboards.com/thread/697/power-world

begins with Dr. James Conca’s concept from a Forbes opinion piece. I take serious objection to building that much more hydropower dams. Dams cause problems as we seriously now notice here in the Pacific Northwest.

Nonetheless, his point is that constructing all those wind turbines, solar panels and nuclear reactors doesn’t actually cost more than BAU. It is just that the costs are capital costs, up front.

On similar lines to the methodology given here by Stefan, echoing these points and with similar results, our McMullin et al. 2019 journal paper on *prudent* (risk averse) *maximum* (minimally equitable) national CO2 quotas came out last month (with a global basis and Ireland used as an example). It also goes a bit further to look at current policies going into CO2 debt, in terms of implied NETs relative to a Paris-aligned national quota.

Can read it here: https://rdcu.be/bJ8pJ

There’s a related summary blogpost here: http://ienets.eeng.dcu.ie/all-blogs/MASGC-McMullin-et-al-2019-AAM

We would very much agree that the exact numbers are not as important as the extreme urgency of climate mitigation action now indicated relative to a realistic Paris-aligned national quota, either: to avoid overshoot of the quota; or, now more realistically for high-per-capita emitters, to limit CO2 debt to minimise tacit commitment to achieving negative emissions.

From this paper, our concluding paragraph:

“In relation to energy systems decarbonisation, the key message from this analysis is that, for

developed countries with heavy fossil fuel reliance, current approaches to decarbonisation are

grossly inadequate. The corresponding risk of catastrophic policy failure is starkly illustrated by the

Low-GCB-Pop CO2-debt trajectories for developed nations (as we show in the case of Ireland),

graphically stating the urgency of near-term action now required particularly to reduce unabated

fossil fuel combustion radically. By contrast, NDC and mitigation gap analyses tend to stress the

long-term and sectoral measures or percentage renewable energy penetration targets that can

divert attention from the urgent mitigation priority of reducing fossil carbon combustion quickly.

From a climate perspective, the core recommendation for both national and global mitigation

strategy must be the prioritisation of achieving nett zero CO2 emissions energy systems within a

stated overarching nett CO2 cumulative quota constraint, limiting commitment to CO2 debt, and

rigorously respecting a nett CO2 emissions rate pathway which is commensurate with satisfying this

cumulative constraint.”

[Response: Thanks, I had not seen that! Given the background of the Paris negotiations, where afaik the “below 2 °C” was very consciously changed to “well below 2 °C”, why you interpret that as meaning the same as “below 2 °C”? How do you justify that? -Stefan]

Whatever we do, we need to be about it:

https://japantoday.com/category/national/57-dead-18-000-taken-to-hospitals-in-week-in-japan-heat-wave

I have become a social leper by being outspoken about the need to reduce recreation-related airtravel and cruise line vacations. These are activities that are largely undertaken and enjoyed by well-to-do folks of my generation who simply won’t accept that this is a reasonable step. I hear a lot of justifications and counter-arguments, but it’s all bs as far as I can tell. So, not much to talk about with my peers these days.

Thanks for clear thoughts on the situation, Stefan.

Mike

re David Benson’s comment (3):

You are right that building enough hydropower to to replace fossil fuels would cause serious environmental consequences. There were serious consequences of damming up the Columbia River, for example.We are spending major amounts of money to maintain salmon runs, which is part of the cost of the hydropower.

However, this is true of all replacement energy sources–the amount of power we need is very large. We have to decide what environmental damage we will accept. This is why it is important to make our energy use more efficient–less energy for more results.

Our website http://www.klima-retten.info/Review.html could be interesting in this context. There several methods are presented to derive national paths from a globally remaining budget. For Germany and the EU concrete reference values are mentioned. We appreciate feedback.

[Response: Thanks! That discusses contraction and convergence, as well as the Raupach formula – I added that paper to the references! Different climate justice schemes can be applied, I’m not claiming my suggestion is the best (just perhaps the most simple). They all have in common that we have to reduce emissions very very fast in the developed world, no matter how you twist and turn it. -Stefan]

This is a great improvement over Vogue‘s analysis of the subject, which reduces the answer to a single number : 420 Gt.

Thank you for doing the example of Germany, and thanks to Paul Price for doing the exammple of Ireland. These examples give a feeling for what the answers look like that come out of this kind of analysis.

Could one of you do the example of China? I think it would be very helpful to see the kind of trajectory change this kind of analysis requires of one of the many countries currently demonstrating rapidly growing emissions, unlike Germany or Ireland.

Thanks also for reminding me about the Meissner et al paper you co-wrote. Been awhile since I read that.

Have you considered doing an update of that paper, breaking the world into the three groups of countries? In that paper the break point for developed countries whose budget would be exhausted in less than 20 years worked out to a per capita emissions above 5.4 t per capita.

China today is at 7.25 t per capita. China currently emits 10.3 Gt per year per the Global Carbon Project. That would seem to require a re-analysis and update from the picture as of 2010 in the Meissner paper.

We need a global direct democracy with internet voting on top of nations. This will also fix several other problems and will take the power away from corporations.

The coloring in the “detrimental effect” graph is confusing.

I would recommend to make the dashed line blue, because it has the same budget as the solid blue line. Also that dashed blue line should begin in 2020, so that the full path can be seen, and the triangles (and their equal areas) created by the solid and dashed blue line are easier to see then.

[Response: Thanks, I guess it’s a matter of taste. To me the red dashed line is a suboption

[Response: of the red path, i.e. of waiting for ten years, and red=bad. -Stefan]

Thanks for this Stefan. However, I think the world is in an emergency (with more heat “in the pipeline” at current net forcing) and should act like it, as if our so-called “budget” of carbonic acid gas is zero. To that end, what would you say to the recent analysis at Scripps that suggests that a completely ice free summer Arctic Ocean would have an effect of one trillion tons, 25 years current CO2 emissions, from the total change in albedo?

Do we have a carbon budget, or a C02 budget? Are we dumping CO2 to the atmosphere, or are we dumping C to an atmosphere that happens to have O2?

[Response: The CO2 budget is 3.7 times the carbon budget (molecular mass of CO2/C, 44/12). -Stefan]

Solar Jim,

You should be ashamed! Bringing holistic thoughts to a discussion is, well, unacceptable. How on Earth can we continue to pretend that Greta is to be ignored if evil scum like you keep spewing facts?

That’s how fast the carbon clock is ticking

“Once the temperature limit has been agreed..,” then we can flap our arms and fly to the moon.

Thank you for this very important article.

As the U.S. is such a large emitter, might you be able to calculate what the U.S carbon budget would be at the start of 2021, when the new U.S. president will take office?

That figure would be useful for the candidates and for U.S. policymakers.

[Response: You can easily do that, with my spreadsheet! -Stefan]

If we’d like to stay under 1.5°C according to the latest IPCC report and 1.5°C is already in the pipeline according to Gavin Schmidt ( https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2018/10/ipcc-special-report-on-1-5oc/ ) and many other climate scientists, then how can we still have a CO2 budget? The global CO2 level has been increased by 135ppm within just roughly 200 years causing horrible consequences already and we are still discussing CO2 budgets while CO2 in the atmosphere is still increasing rapidly? I don’t get it. It’s because of “political constraints”, right? Yes, it is.

” Finally, unprecedented global cooperation is needed to tackle the climate crisis.”

Guess what, I hear that for decades. It’s all just a political poker game, betting on cards that don’t exist. Politics will use that none-existing “budget” joker card to go on with BAU, “just for some few more years” as they act exactly like junkies:

” Uhm, yeah, fossil fuels are bad, but there is still some “budget”, so we promise to get clean tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow (never comes), but we need another shot just for today”.

Haha, that’s exactly the game that’s going on way too long and it will lead to a global desaster never seen before.

Thanks for a nice clear presentation. I’ll be sharing this piece.

@ Dr. Rahmstorf

Thank you very much for yet another essential must-read article!

Just a note: I tried to download your spreadsheet to work out the CO2 emissions budget for the US, France and a few other countries, but unfortunately the link to your spreadsheet is not working.

Also, if I may express one agonizing issue that I have with any remaining carbon budget calculations:

1- It appears that as of July 2019, we are around 1.1~1.2C above the 1880-1900 mean, or pre-industrial.

2- There is another 0.5~1C warming “in the pipeline” since we are far from having reached the equilibrium temperature for the CO2 atmospheric concentration level that we are likely to peak at.

3- There will be another 0.3~1C extra warming as we reduce the amount of aerosols in the atmosphere, with the subsequent reduction in the global dimming effect.

So I am rather confused as to the existence of a remaining carbon budget to stabilize global temperatures at +1.5C above pre-industrial, since just from 1, 2 and 3 above, and not even taking into account any further feedbacks such as the probable disappearance of summer Arctic sea ice, the ongoing thawing of permafrost, etc, even if we stopped all GHG emissions instantaneously today (and obviously that won’t happen, we haven’t even globally peaked emissions), the planet would reach 1.9~3.2C above pre-industrial.

[Response: The link should be fixed. The IPCC SR15 discusses this issue of “in the pipeline warming”. In short, it is not such a big issue as you think; maybe others can weigh in. -Stefan]

At present rates we’ll have exhausted the global carbon budget by the year 2030. Ag present rates, in the year 2030 the atmospheric CO2 will be almost 440 ppm.

Maybe we should monitor progress by how well we keep CO2 from going over 440 ppm.

mike: I have become a social leper by being outspoken about the need to reduce recreation-related airtravel and cruise line vacations.

Abhaya: As the U.S. is such a large emitter, might you be able to calculate what the U.S carbon budget would be

AB: Irrelevant. The issue is per person not per country. Have YOU exceeded YOUR budget? That’s the question. The answer is, of course, if you ain’t poor you’re way way way in debt.

@Al Bundy, #22

” The issue is per person not per country. Have YOU exceeded YOUR budget? That’s the question. The answer is, of course, if you ain’t poor you’re way way way in debt.”

You nailed it perfectly. I hear “uhm, I can’t change my neighbour nor my country and my country can’t change other countries, so it’s useless to change my habits” all day long. Funny games on the way to hell.

Thank you for the article. While the technical material is above my maths ability, I especially appreciate bringing Greta Thunberg into the subject matter.

There is, sadly, decreasing hope that we all will take this seriously enough to reverse our habits, since we’re already 40 years behind the clock on action.

I would, however, emphasize that paying attention to waste is a good way to raise one’s consciousness.

h/t to Russell for the British Vogue reference. His snark is often chortle-worthy and I hadn’t known about that excellent effort.

The rule, as I recall, is as simple as possible but no simpler.

In this regard, I think the first two steps of your argument are just simple enough. I particularly like your finesse with respect to feedbacks question.

But when it comes to step 3, you have (quite consciously) gone for an argument that is too simple. I think I understand why — keeping it simple makes the main point, “that we have to reduce emissions very very fast in the developed world, no matter how you twist and turn it” clear.

But, still, it’s no good. Per-capita is, finally, unfair, which is why Contraction and Convergence never really had any traction. The fact of the matter is the the operational principles here are capability (which means wealth) and responsibility (which means facing history).

Want to see what this means in practice? Take a look at the Climate Equity Reference Calculator, https://calculator.climateequityreference.org/

@ Dr. Rahmstorf

Thank you very much for your reply and pointing me to the IPCC SR15, which discusses the warming commitment from past emissions in Section 1.2.4.

Thank you also for fixing the link to your spreadsheet, which I have downloaded.

Quoting from SR15, Section 1.2.4:

“Expert judgement based on the available evidence (including model simulations, radiative forcing and climate sensitivity) suggests that if all anthropogenic emissions were reduced to zero immediately, any further warming beyond the 1°C already experienced would likely be less than 0.5°C over the next two to three decades, and also likely less than 0.5°C on a century time scale.”

The SR15 report was published in October 2018 with data I believe up to December 2017, this is why it mentions “the 1°C already experienced”. According to the WMO, 2018 was 1.1°C above pre-industrial and as of July 2019 we are 1.2°C above pre-industrial. It seems global average temperatures are rising faster than predicted by the “expert judgement” mentioned in the SR15 report: a measured 0.2C in two (non El Niño) years is much faster than “likely less than 0.5°C over the next two to three decades”.

I took the liberty of revising your remaining carbon budget per country spreadsheet taking into account the measured 0.2°C increase in global average temperature in 2018 and the first six months of 2019, so I simply decreased the value in cell D11 (from 580 to 300).

The result of this is that for example the US as of July 2019 has approx. zero remaining carbon budget if we are to have a 2/3 chance of staying below 1.5°C warming above pre-industrial.

As of July 2019, France still has 7 years at current emissions rates, Germany has 2.4 years, China has 4 years, India has 24 years, Australia has zero budget remaining, Brazil has 20 years, etc.

Since none of these countries has in place any policies (afaik) to force down their carbon emissions to net zero before 2050, I remain skeptical that we can keep global warming below 1.5°C above pre-industrial, based on any policies that take the global remaining carbon budget into account.

Typo in fourth-from-last paragraph (“First of all…”): recude–>reduce.

And thank you for another worthy effort, Dr. Rahmstorf.

Andrew, #27–

You’re comparing apples and oranges. Yearly values of GMST can easily vary by 0.1 C or more, and monthly values by more than that. So there’s a very good chance that what you’re observing isn’t so much trend as variability.

Consider: for the last 40 years, the linear warming trend has been relatively stable (albeit with quite a lot of short term variability), with upper values for 20-year periods and longer pretty consistently in (roughly) the range of 0.1-0.2 C per *decade*. I really doubt that 2017 marked the start of a new regime in which warming accelerated 10-fold.

None of which, of course, is to deny that we are thoroughly in the soup.

It seems to me that game-theoretically one should support the global carbon tax + full dividends to citizens within a country + WTO tariffs against countries with relaxed policies. As I understand, WTO regulations already allow for that. IPCC would set the annual price for carbon. The historical blame and possible reparations should be decoupled from the global carbon price for the markets to operate efficiently. The whole AGW fiasco so far has been due to the inability to negotiate “fair country quotas”, a global carbon tax would eliminate (set aside) that problem. But alas, we seem to continue to make the same mistakes again and again. What happened to the support to the Hansens’s carbon tax & dividend?

If Al wishes to be lionized rather than leperized, he should evangelize the sailing cruise ship revival- if Greta Thunberg had any sense she’d skip the ULD racing sled and cross the Atlantic on Sweden’s Star Clipper line, whose five masted flagship generates enough power under sail to light the lights and run the winches, stabilizers and air conditioning.

There are alternatives of course, but many require further development

Questions:

1) Did like the weather in the last 2 years?

It will NOT get better in your lifetime.

2) Will you do something to keep it from getting worse?

If everybody on earth does something it might not get worse!

3) Do you know what to do when it gets bad?

I do not know either. Please help me!

As others have pointed out, there is no carbon budget left. The last time CO2 levels were TODAY’S value (around 410 ppm), sea levels were about 75 feet higher than today (and that’s were we are heading, even if we stopped emitting today). We see the Arctic sea ice melting towards zero with TODAY’S CO2, as well as the permafrost beginning to melt (and it holds about twice the CO2 that the atmosphere holds). As Jim Hansen said a while ago, the maximum possible safe level of CO2 is 350 ppm. Why are we talking about budgets to take us to further unsafe levels?

There is a school of thought (which is, unfortunately, probably valid) that says it is impossible to avoid catastrophe by ONLY reducing emissions (and we are not reducing emissions in any case). Therefore, we should be focused on “Climate Restoration” by countering Arctic sea ice loss and extracting CO2 from the atmosphere using accelerated natural processes and well as mechanical Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR). All these things are possible if we have the proper incentive structure. But current incentives favor the burning of fossil fuels. The proper immediate step to take is to put a rising price on carbon using the Fee and Dividend policy (so the price is known in advance and grows to a high value) and start to make fossil fuels pay closer to their true cost to society. There are many other things we also need to do, but until we put a real, growing, known-in-advance price on carbon, talk of getting serious about climate change is just talk.

OK, Let’s suppose all this is true. Is it really possible for example to go more strongly to renewables than Europe? As the graph shows, Germany for example needs to do much much more. Something like pumped water storage would seem to be essential for wind and solar to take over most electricity generation. Batteries are not practical or cost effective and they are environmentally dirty. Large pumped storage involves a lot of changes in environmentally sensitive areas, creation of new reservoirs, etc. This will all take a level of political will that I personally see as unlikely. Even in California, I don’t see a real effort to do any of this. Nuclear remains mired in Green obstruction. Even after Obama eased regulations, nothing is happening in the US. Any other ideas aside from hand wringing and virtue signaling?

dpy6629 – Finding the political will is more of problem than technology. Environment cost of renewables seems better than environmental cost of climate change. Some obvious steps would kill fossil fuel subsides (IMF report here). Levelized cost of generation (see here for instance but others similar) make nuclear a non-starter from economics rather political obstruction. Simple stuff like ban any new FF generation and let market sort out how the best alternative. Phase out FF cars are many countries are doing. Dont be a NIMBY and just get on with it. Doesnt take much effort to find alternative plans if you look.

We are already of 1 deg of warming, and recent studies consider that aerosols mask as much as 0.5 deg of warming so I think we can stop this nonsense about keeping warming to 1.5 deg. Furthermore, as far as I know, the 2 deg scenarios require negative emissions. Why is this not discussed?

Also, why are we still talking about countries? We all know that western countries have moved a lot fo their manufacturing to the developing world, and as such their emissions are a product of our own consumption habits. Why are scientists not taking this into account?

Could or should a similar calculation be made on a personal level, i.e. the CO2 budget of an individual or family? What is the personal CO2 maximum that is allocated for a person/family in Germany? At 340 Gt remaining CO2 to meet the target outlined in your article and assuming a linear depletion in 17 years to zero, we are talking about an annual drawdown of 40 Mt/year. Given Germany’s population of 83 million, that’s a per capita 2019 budget of 9.6 tons which shrinks to 1.9 tons CO2/yr for 2035. According to a quick internet search, approximately 70% of all CO2 emissions in Germany are attributable to direct and indirect household use. Assuming an average 3-person household, there are 28 million households in Germany. Assuming further a 70% contribution to total CO2 emissions, the household 2019 budget ought to be 20.1 tons/year shrinking to 4 tons/year by 2035 and then to nil. This means a 5% CO2 reduction in the first year dropping to 20% by 2035 compared to 2034.

I am often confronted by the question after talks on the effects of climate change (I am a geoscientist trying to decipher the effects of climate change on a certain type of landslide process in western Canada), what the individual can do to reduce CO2 emissions. I believe what (hopefully) applies to national policies as outlined in Stephan’s article should be calculated (of course with more nuance as I am doing here) for the individual or household. If government were to publish and promote such numbers, a certain portion of the population may take it seriously, determine their CO2 budget (as there are plenty of such tools on the web) and attempt to meet their personal targets year by year, and probably at a substantial cost saving due to a reduction in flights, meat eating and perhaps the one child less mantra propagated by some. I believe one ought not rely on government to rigorously put mechanisms in place to meet the zero emission target in 17 years while catering to the mandates of perpetual growth of Germany’s export-oriented economy and powerful industrial lobbyists. For that to happen, a draconian Marshall-type plan would have to be instituted immediately, but there is no such thing, at least in Germany that aims to reduce CO2 emission to 0 by 2035. Hence, it may be wise to deflect at least some responsibility to individuals with guidance on the right tools on how to reduce one’s CO2 footprint. It turns out that in Germany the term Verzichtsgesellschaft (renunciation society) is a hotly debated issue, and new nouns such as Flugscham (shame of flying) are being coined. This certainly does signal awareness if nothing else!

Current and past battery costs:

https://data.bloomberglp.com/bnef/sites/14/2017/07/BNEF-Lithium-ion-battery-costs-and-market.pdf

Required storage costs:

https://www.cell.com/joule/fulltext/S2542-4351(19)30300-9

“Energy storage capacity below $20/kWh could enable cost-competitive baseload power”

Looks like batteries will still need to come down in cost from $273 per Kwhour (2016) to ~$20 per Kwhour. And by 2030 Bloomberg forecasts $73 per Kwhour, still a factor of 4 too high.

Pumped storage could be easy to retrofit in many areas with pre-existing large reservoirs. Unfortunately these areas tend to not be that good for solar and wind.

#34, dp(etc)–

What makes you think that?

Some quick and semi-random cases in point:

https://electrek.co/2018/01/23/tesla-giant-battery-australia-1-million/

https://www.pv-magazine.com/2014/12/03/solar-plus-storage-becoming-new-normal-in-rural-and-remote-australia_100017360/

https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/solar-plus-storage-can-beat-standalone-pv-economics-by-2020#gs.uoo48t

https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/florida-power-light-to-build-409-megawatt-solar-powered-battery-system#gs.uoo7na

Lazard’s 2018 cost analysis of storage, showing why Li-plus-solar is taking off:

https://www.lazard.com/perspective/levelized-cost-of-energy-and-levelized-cost-of-storage-2018/

From the above, I would conclude that batteries are clearly 1) practical, since they are in use, making money, and gaining in popularity; and 2) increasingly cost-effective, though not yet suited to all use cases.

Certainly battery manufacture can and does have environmental impacts, as does virtually any type of manufacturing. I’m not aware that it’s especially ‘dirty’ compared with many other types of industries; perhaps you have some specific information?

One question mark for battery storage, I think, is scalability. The main prospect for decarbonizing transportation is BEV tech, which is rapidly gaining ground in the marketplace (albeit still at a low proportional market share). As BEVs become much more numerous, as I think it’s clear they will, demand for batteries will grow enormously, too. That takes raw materials and fabrication plants, of course, and it’s unclear (to me, at least) just how fast these can grow. (Though it’s worth noting that expectations of lithium shortages have so far been, to put it charitably, massively oversold. Glad I resisted the temptation to buy any of those lithium-mining penny stocks…)

#39, DY–

Great link, that BNF piece. But you could have quoted the bit that said:

Otherwise, the bit you *did* quote could mislead.

I’m going to be a bit heretical here, and say that I think the whole concept of “baseload” is on the way out. We’ll be looking at a grid that’s more dynamic, since we know have the means–i.e., software and hardware–to manage such an environment, and technologies well-suited to such an approach. IMO, of course.

David Young @39, Australia has some interesting plans for pumped hydro storage, and this coincides with good solar and wind power potential more or less within the same regions:

https://www.ft.com/content/dbc4f49a-7fe7-11e9-b592-5fe435b57a3b

Kevin McKinney, With respect, your links are mostly glossy press reports which are notoriously unreliable. Your final link seems to directly contradict my references on battery costs. If in fact Lazzard was right I would expect to see a huge rush to solar among US utilities most of which are after all mostly public utilities. That is not happening. The Florida example you cited is a very small facility BTW.

The modern era is full of yellow journalism with the media having descended to the hyper partisanship and sensationalism of the 19th Century. In addition science is often unreliable too because of changes to scientific culture. The soft money culture has led to structural motivations to exaggerate and cherry pick and shade the data.

https://www.nature.com/news/registered-clinical-trials-make-positive-findings-vanish-1.18181

https://www.significancemagazine.com/2-uncategorised/593-cargo-cult-statistics-and-scientific-crisis

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsos.160384

The bottom line on renewables is that they make a very small contribution to world energy supply despite 20 years of huge investments and government subsidies. Technology needs to advance dramatically for mitigation to be politically palatable. Bill Gates is right just as he was when he bought DOS from IBM.

I am quite confident that renewables will become truly cost effective in the future. We should spend money on the technology to do that. I don’t think artificial deadlines and panicked talk about reducing emissions to zero by 2050 are useful. These deadlines are artificial and the scientific basis is weak as Nic Lewis has shown.

Kevin Mc, I dug into your final Lazzard link and the top line chart is misleading. It must be without storage. When you look further there is a chart for Photovoltaic with storage and it agrees largely with the Bloomberg and MIT links I provided.

Bottom line, Lazzard did a poor job of highlighting the true costs of their alternative energy solutions. Why would they do that?

So Kevin, your 5 links are unimpressive. If you have something better I’d be happy to look at it.

I think there is a key flaw in the carbon budget, namely an under estimate of the size of “Earth System Feedbacks”, the orange highlighted column in table 2.2 from IPCC SR15. The estimate of -100 GT over a century is outdated. The recent physical measurements of the albedo effect of melting sea ice, in ‘Radiative heating of an ice-free Arctic Ocean’ by Pistone K, Eisenman I and Ramanathan V published in PNAS, are much more reliable than the simple model estimates relied on in IPCC SR15. The observed additional sea ice albedo effect must cause more rapid and larger permafrost release of carbon due to increased ocean warmth and due to additional fire caused feedbacks from warmer arctic land surface temperatures that are also causing increased fires. The observation of significant additional amplification not included in the old modeled estimate for earth system feedbacks means the carbon budget remaining is overestimated and may already be used up.

dpy6629 @43

It’s true that mass scale lithium battery storage is still essentially expensive, however the trend is falling prices and I came across this a while back. Just thought I would throw it into the discussion. These are proposals to replace specific aging coal fired plants with packages that combine various renewable options and storgare options including battery storage, and the overall economics look good so the costs of battery storage are not a problem in this overall package. They would not be proposing them otherwise:

https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/xcel-retire-coal-renewable-energy-storage#gs.viue55

https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/pacificorps-march-from-coal-toward-clean-energy-alternatives#gs.vitmp1

“I don’t think artificial deadlines and panicked talk about reducing emissions to zero by 2050 are useful. These deadlines are artificial and the scientific basis is weak as Nic Lewis has shown.”

Nic Lewis doesn’t make a lot of sense for example:

https://www.thegwpf.com/climate-scientist-nic-lewis-european-co2-emissions-dont-matter/

I mean where would you even start with this? Many of his statements are just empty assertions and blatant contradictions and an unexplained preference for nuclear power over renewable energy, unfounded claims the earth hasn’t warmed as much as models predicted and other denialist talking points. This is not the person we should be listening to.

Nigel, Greentechmedia looks to me like many of their articles are slanted towards green technology. The first link says Colorado will save money by replacing existing coal plants with renewables. This is contradicted by MIT and Bloomberg. Perhaps Colorado is using inadequate storage and counting on their gas generation or perhaps they are getting subsidies.

Nic Lewis has done a careful carbon budget analysis using observationally constrained models and comes up with a number that is 80% higher than the IPCC for the 2 degree C target.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cYZW-6jw98U&t=2970s

Nic is generally very respected and is regularly invited to workshops on climate sensitivity. His work is taken seriously by climate scientists. Your smear is just an attempt to discredit someone whose science you don’t like.

dp…, #42 & 3–

A slightly more sophisticated version of “fake news.” There’s no justification for “glossy”, other than to belittle by implication. You are unimpressed by the stories; I’m unimpressed by your attempts to dismiss them.

I think your smear is particularly inapropos with regard to the third link, which is a sufficiently granular news account of a new NRL study as to scream “policy wonk.” Well, maybe not scream. “Say loudly.”

From the story that you apparently didn’t read very thoroughly:

“Expected to be up and running by late 2021, the FPL Manatee Energy Storage Center will be a landmark project for the storage sector, four times the size of the world’s largest battery system currently in operation, FPL said in a statement.”

So, in the relevant context, not small at all.

Correct. That’s why the bottom chart is labeled “Storage.” (For that matter, that’s why the entire piece is headed “Levelized Cost of Energy and Levelized Cost of Storage 2018.”) (My emphasis.)

With respect, you did a poor job of reading their piece–but I’m sure it was inadvertent. In my mind, the relevant item is the entry for PV plus solar, which is now undercutting gas peakers in the southern US–and the economic dividing line is marching north. (This fact is also alluded to in the ‘Joule’ item you linked. I would remark that that piece is well-worth reading; it has a *lot* more nuance than one would think from the conclusions you take from it.)

I can’t agree with this, either. The affordability of renewables was a major factor in bring developing nations such as India onboard the Paris Accord. The fact that India, for instance, has added over 20GW from 2015 to the end of 2018 illustrates that this decision was more than just lip service.

https://public.tableau.com/views/IRENARETimeSeries/Charts?:embed=y&:showVizHome=no&publish=yes&:toolbar=no

“…added over 20GW *of solar capacity alone* from 2015 to the end of 2018…”

Sorry for the omission.

dpy6629 says:

“This is contradicted by MIT and Bloomberg. ”

So you say. Please provide poof with a link, and it needs to relate specifically to the cases in point and not be a general theoretical opinion about renewables otherwise its not going to be convincing for anyone.

“Perhaps they are getting subsidies”

This is just speculation. Show me proof, and show me whether it would change the conclusions in the articles I posted.

“Nic Lewis has done a careful carbon budget analysis using observationally constrained models and comes up with a number that is 80% higher than the IPCC for the 2 degree C target.”

This is not convincing, and uses low climate sensitivity numbers below what is generally accepted and numbers based on observations of a narrow period of global temperatures. Please note that temperatures since 2015 show that models are not underestimating climate change significantly. The IPCC and expert commentators and simple logic suggests the direct opposite, namely we have very little carbon budget left.

“Your smear is just an attempt to discredit someone whose science you don’t like.”

I didn’t smear him. Instead I pointed out obvious and indisputable deficiencies in what he has claimed. Shame you are in denial about this, and notable you haven’t been able to refute what I said.