Guest post by Veronika Huber

Guest post by Veronika Huber

Climate skeptics sometimes like to claim that although global warming will lead to more deaths from heat, it will overall save lives due to fewer deaths from cold. But is this true? Epidemiological studies suggest the opposite.

Mortality statistics generally show a distinct seasonality. More people die in the colder winter months than in the warmer summer months. In European countries, for example, the difference between the average number of deaths in winter (December – March) and in the remaining months of the year is 10% to 30%. Only a proportion of these winter excess deaths are directly related to low ambient temperatures (rather than other seasonal factors). Yet, it is reasonable to suspect that fewer people will die from cold as winters are getting milder with climate change. On the other hand, excess mortality from heat may also be high, with, for example, up to 70,000 additional deaths attributed to the 2003 summer heat wave in Europe. So, will the expected reduction in cold-related mortality be large enough to compensate for the equally anticipated increase in heat-related mortality under climate change?

Due to the record heat wave in the summer of 2003, the morgue in Paris was overcrowded, and the city had to set up refrigerated tents on the outskirts of the city to accommodate the many coffins with victims. The city set up a hotline where people could ask where they could find missing victims of the heatwave. Photo: Wikipedia, Sebjarod, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Some earlier studies indeed concluded on significant net reductions in temperature-related mortality with global warming. Interestingly, the estimated mortality benefits from one of these studies were later integrated into major integrated assessment models (FUND and ENVISAGE), used inter alia to estimate the highly policy-relevant social costs of carbon. They were also taken up by Björn Lomborg and other authors, who have repeatedly accused mainstream climate science to be overly alarmist. Myself and others have pointed to the errors inherent in these studies, biasing the results towards finding strong net benefits of climate change. In this post, I would like to (i) present some background knowledge on the relationship between ambient temperature and mortality, and (ii) discuss the results of a recent study published in The Lancet Planetary Health (which I co-authored) in light of potential mortality benefits from climate change. This study, for the first time, comprehensively presented future projections of cold- and heat-related mortality for more than 400 cities in 23 countries under different scenarios of global warming.

Mortality risk increases as temperature moves out of an optimal range

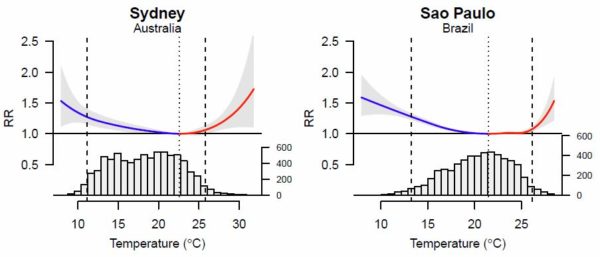

Typically, epidemiological studies, based on daily time series, find a U- or J-shaped relationship between mean daily temperature and the relative risk of death. Outside of an optimal temperature range, the mortality risk increases, not only in temperate latitudes but also in the tropics and subtropics (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Exposure-response associations for daily mean temperature and the relative mortality risk (RR) in four selected cities. The lower part of each graph shows the local temperature distribution. The solid grey lines mark the ‘optimal temperature’, where the lowest mortality risk is observed. The depicted relationships take into account lagged effects over a period of up to 21 days. Source: Gasparrini et al. 2015, The Lancet.

Furthermore, the optimal temperature tends to be higher the warmer the local climate, providing evidence that humans are at least somewhat adapted to the prevailing climatic conditions. Thus, although ‘cold’ and ‘warm’ may correspond to different absolute temperatures across different locations, the straightforward conclusion from the exposure-response curves shown in Fig. 1 is that both low and high ambient temperatures represent a risk of premature death. But there are a few more aspects to consider.

Causal pathways between non-optimal temperature and death

Only a negligible proportion of the deaths typically considered in this type of studies are due to actual hypo- or hyperthermia. Most epidemiological studies on the subject consider counts of deaths for all causes or for all non-external causes (e.g., excluding accidents). The majority of deaths due to cold and heat are related to existing cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, which reach their acute stage due to prevailing weather conditions. An important causal mechanism seems to be the temperature-induced change in blood composition and blood viscosity. With regard to the cold effect, a weakening of the defense mechanisms in the airways and thus a higher susceptibility to infection has also been suggested.

Is the cold effect overestimated?

As in any correlative analysis there is always the risk of confounding, especially given the complex, indirect mechanisms underlying the relationship between non-optimal outside temperature and increased risk of death. Regarding the topic discussed here, the crucial question is whether the applied statistical models account sufficiently well for seasonal effects independent of temperature. For example, it is suspected that the lower amount of UV light in winter has a negative effect on human vitamin D production, favoring infectious diseases (including flu epidemics). There are also some studies that point to the important role of specific humidity, that, if neglected, may confound estimates of the effect of temperature on mortality rates.

Interestingly enough, there is still an ongoing scientific debate regarding this point. Specifically, it has been suggested that the cold effect on mortality risk is often overestimated because of insufficient control for season in the applied models. On the other hand, the disagreement on the magnitude of the cold effect might simply result from using different approaches for modeling the lagged association between temperature and mortality. In fact, the lag structures of the heat and cold effects are distinct. While hot days are reflected in the mortality statistics relatively immediately on the same and 1-2 consecutive days, the effect of cold is spread over a longer period of up to 2-3 weeks. Simpler methods (e.g., moving averages) compared to more sophisticated approaches for representing lagged effects (e.g., distributed lag models) have been shown to misrepresent the long-lagged association between cold and mortality risk.

Mortality projections

But what about the impact of global warming temperature-related mortality? Let’s take a look at the results of the study published in The Lancet Planetary Health, which links city-specific exposure-response functions (as shown in Fig. 1) with local temperature projections under various climate change scenarios.

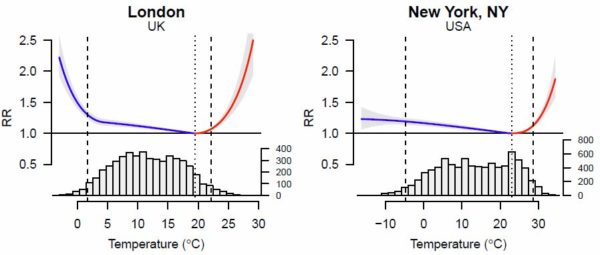

Fig. 2 Relative change of cold- and heat-related excess mortality by region. Shown are relative changes per decade compared to 2010-2019 for three different climate change scenarios (RCP 2.6, RCP 4.5, RCP 8.5). The 95% confidence intervals shown for the net change take into account uncertainties in the underlying climate projections and in the exposure-response associations. It should be noted that results for single cities (> 400 cities in 23 countries) are here grouped by region. Source: Gasparrini et al. 2017. The Lancet Planetary Health

In all scenarios, we find a relative decrease in cold-related mortality and a relative increase in heat-related mortality as global mean temperature rises (Fig. 2). Yet, in most regions the net effect of these opposing trends is an increase in excess mortality, especially under unabated global warming (RCP 8.5). This is what would be expected from the exposure-response associations (Fig. 1), which generally show a much steeper increase in risk from heat than from cold. A relative decline in net excess mortality (with considerable uncertainty) is only observed for Northern Europe, East Asia, and Australia (and Central America for the more moderate scenarios RCP 2.6, and RCP 4.5).

So, contrary to the propositions of those who like to stress the potential benefits of global warming, a net reduction in mortality is the exception rather than the rule, when comparing estimates around the world. And one must not forget that there are important caveats associated with these results, which caution against jumping to firm conclusions.

Adaptation and demographic change

As mentioned already, we know that people’s vulnerability to non-optimal outdoor temperatures is highly variable and that people are adapted to their local climate. However, it remains poorly understood how fast this adaptation takes place and what factors (e.g., physiology, air conditioning, health care, urban infrastructure) are the main determinants. Therefore, the results shown (Fig. 2) rely on the counterfactual assumption that the exposure-response associations remain unchanged in the future, i.e., that no adaptation takes place. Furthermore, since older people are more vulnerable to non-optimal temperatures than younger people, the true evolution of temperature-related mortality will also be heavily dependent on demographic trends at each location, which were also neglected in this study.

Bottom line

I would like to conclude with the following thought: Let’s assume – albeit extremely unlikely – that the study discussed here does correctly predict the actual future changes of temperature-related excess mortality due to climate change, despite the mentioned caveats. Mostly rich countries in temperate latitudes would then indeed experience a decline in overall temperature-related mortality. On the other hand, the world would witness a dramatic increase in heat-related mortality rates in the most populous and often poorest parts of the globe. And the latter alone would be in my view a sufficient argument for ambitious mitigation – independently of the innumerous, well-researched climate risks beyond the health sector.

Addendum: Short-term displacement or significant life shortening?

To judge the societal importance of temperature-related mortality, a central question is whether the considered deaths are merely brought forward by a short amount of time or whether they correspond to a considerable life-shortening. If, for example, mostly elderly and sick people were affected by non-optimal temperatures, whose individual life expectancies are low, the observed mortality risks would translate into a comparatively low number of years of life lost. Importantly, short-term displacements of deaths (often termed ‘harvesting’ in the literature) are accounted for in the models presented here, as long as they occur within the lag period considered. Beyond these short-term effects, recent research investigating temperature mortality associations on an annual scale indicates that the mortality risks found in daily time-series analyses are in fact associated with a significant life shortening, exceeding at least 1 year. Only comparatively few studies so far have explicitly considered relationships between temperature and years of life lost, taking statistical life expectancies according to sex and age into account. One such studies found that, for Brisbane (Australia), the years of life lost – unlike the mortality rates – were not markedly seasonal, implying that in winter the mortality risks for the elderly were especially elevated. Accordingly, low temperatures in this study were associated with fewer years of life lost than high temperatures – but interestingly, only in men. Understanding how exactly the effects of cold and heat on mortality differ among men and women, and across different age groups, definitely merits further investigations.

> Dan H. … daytime highs and number of days exceeding high temperatures

> (whether it be 90, 95, or 100F) has decreased in most major cities

Once yet again, “Dan H.” — Please cite a source for the beliefs you post.

We shouldn’t have to keep reminding you about that.

If you’re ashamed of your sources, perhaps you should be. Think about it.

Here’s an example of a citable source:

http://www.climatesignals.org/data/record-high-temps-vs-record-low-temps

See on that page where they give you a link to their sources? Here it is:

http://www.climatesignals.org/reports

Hank Roberts quotes NPR: Those victims were generally women, living alone and over the age of 75. “Oftentimes, they won’t have their air conditioning on, or it will be malfunctioning,” says Sunenshine.

AB: Just for information, the public library is a grand refuge. Instead of burning carbon and blowing your budget, head to where you can get social interaction, free internet, and plenty of intellectual stimulation.

——

Mr KillingInaction: On a 95 degree day you can probably kill yourself by doing a hard workout in the sun and not drinking enough water – people have been demonstrating this exact feat for thousands of years.

AB: Yes, and Muslims are at an incredible risk. When your religion says that during certain (varying) times of the year you aren’t allowed to drink water during the day, you get to either die or go to Hell.

KIA: Trump [snip] is a friggin’ genius, best president in my 60+ years! Most entertaining in our history I’ll bet!

AB: You are equating entertainment with intelligence. Dumb, dumb, dumb conclusion. Monkeys in the zoo are entertaining, too. Trump is destroying the USA and the planet because he’s an ignorant low-IQ psychopath who gets by because his grandfather changed his actual name “Drumpf” to “Trump” and his father was a racist thief and Drumpf himself goes bankrupt on a regular basis so as to screw hardworking folks out of their rightful pay for hard work. Drumpf can’t divulge his tax returns or his Russian connections because doing so would expose the fact that he’s scum. We’ll see if he ends up where he belongs… in prison. Seriously, look up ANY non-partisan insider’s comments about him. They ALL say he’s stupid, ignorant, and (those who “go there”) evil.

And, by the way, I post towards you the way I do because I’m certain that it gives you a chuckle. If I offend you, just let me know.

Hank,

https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-high-and-low-temperatures

http://www.drroyspencer.com/wp-content/uploads/US-extreme-high-temperatures-1895-2017.jpg

Why would I be ashamed of the epa or noaa?

As an example, New York City has exceeded 100 degrees F less over the past three decades, than earlier in the 20th century:

2010s: 5

2000s: 1

1990s: 8

1980s: 2

1970s: 3

1960s: 4

1950s: 12

1940s: 8

1930s: 8 (including record high of 106F)

1920s: 2

https://www.weather.gov/okx/100degreedays

A similar trend has been seen in other major cities, such as Chicago.

Hank@152

Yes, that link supports my contention of rising low temperatures. Hence the ratio of record highs to record lows has decreased significantly.

Dan H @154

You previously tried to deny / downplay increasing heatwave trends in the USA.

Your own EPA source shows the opposite. It clearly states “Nationwide, unusually hot summer days (highs) have become more common over the last few decades (see Figure 2). The occurrence of unusually hot summer nights (lows) has increased at an even faster rate. This trend indicates less “cooling off” at night…” Figure one clearly depicts an increasing trend in the annual heat wave index from 1960 – 2018.

You say: “As an example, New York City has exceeded 100 degrees F less over the past three decades, than earlier in the 20th century. Chicago is similar”

So what? You quote just two cities. This is not representative of America as a whole, and is completely useless analysis.

“Yes, that link supports my contention of rising low temperatures. Hence the ratio of record highs to record lows has decreased significantly.”

So what? This doesn’t make things better.

140 – nigelj

nigelj:

“……. air conditioning is essential in some places.

I dont really need air conditioning, except it gets a bit hot at night for about two weeks in summer. I have considered getting an evaporative cooler, ( a very basic air conditioner) which might use less electricity so should be less of a problem, (I must look into that). ”

MKIA: Is AC essential in some places as you suggest? Apparently not. Thousands of years went by without it and enough people survived. Is it better with it? Many times yes, but it is also good to use less energy intensive ways to achieve comfort when possible.

Don’t know where you live, thus can’t say if an evaporative cooler would help you much, BUT if others around you use them, then perhaps they work – ask your neighbors. In higher humidity areas they don’t do well, but if the air is dry they’re as good as refrigerated air conditioning, but they do add H2O, a GHG, to the air. Perhaps the scientists can tell us if added H2O using evap coolers is better than belching more CO2 to power a refrigerated air conditioner. Evap cooler still has to have a supply air fan, a pump, and sometimes an exhaust air fan, but the power draw should be lower than a traditional AC unit.

In the mean time, nigelj, you can reduce the solar gain thru your windows by putting aluminum foil on them and perhaps putting some insulation behind that. Rigid foam insulation is sold here in the US that is 2′ x 4′ x 1/2″ (up to 3″ thick), and some of it has a reflective foil face. The 1/2″ sheets can be placed inside your windows, foil out, and will cut the heat gain quite a bit. Also, there are bamboo devices that hang on the outside of your windows to prevent the sun from even getting thru one layer of glass; same with awnings – best to not let the sun hit the glass at all. Good luck fighting the heat.

I would like to see legislation that allows home owners to put up shading devices, solar heating devices, PV panels, etc for better energy efficiency and self-sufficiency even when local regulations such as HOA CC&Rs and local building codes don’t allow them. This would open up the possibility for big employment opportunities and less consumption of power and fuels.

Mr KIA @157, the trouble is air conditioning has become virtually essential in some situations. High rise glass faced towers are sometimes virtually uninhabitable if the power fails in summer.

Climates with high temperatures plus humidity can actually have lethal conditions without air conditioning, at least for the old and frail. This will become more common with climate change.

But anyway, yes the best way to keep heat out of your house is some sort of screen on the outside of the glazing like an awning, shutter or whatever. Stop the heat before it gets inside, because not all of it will radiate back through the glass even with solar curtains. Tin foil is a cheap and cheerful version I suppose. But none of this is so easily applicable to commercial buildings.

But these are all going to be ambulance at the bottom of the cliff solutions to global warming.

KIA, #157–

Ooh! I know! I know!

Yes, it’s better because:

1) There’s unlikely to be a net addition of water to the Earth system (though it’s possible if the water was drawn from a deep aquifer, but even then the addition is a minuscule proportion of stocks (ie., the world ocean));

2) H2O is not long-lived in the atmosphere, typically being precipitated out in a matter of days. That’s why, despite the power of H2O as a greenhouse gas, it does not act as a climate ‘control knob.’ Put another way, a gram of water emitted to the atmosphere is going, over the lifetime of the planet, to be spending far more time in the ocean than anywhere else.

Expanding a bit, per the USGS, Earth has about 1.4 billion km3 of water, with about 13,000 km3 in the atmosphere at any one time. (On point 2, that suggests that ‘far more time in the ocean’ really means a million times more duration.)

https://water.usgs.gov/edu/earthhowmuch.html

Continuing to expand, at a billion tonnes per cubic kilometer, that’s ~ 13 trillion tonnes of water in the atmosphere, or 1.3 x 10e17 kg–if I’ve kept my exponents straight all the way through the calculation.

Getting back to point #1, the mass of *CO2* in the atmosphere is about 3 x 10e15 kg.

https://water.usgs.gov/edu/earthhowmuch.html

So adding fossil water to the atmosphere is per mass unit on the order of 100 times less effective proportionately than is adding fossil CO2–even before you try to account for the differences in atmospheric residence time. Denialati sometimes riff about how ‘tiny’ the proportion of CO2 in the atmosphere is, but in a way that’s the whole point; if the proportion weren’t relatively small, it would be much more resistant to human modification than it is.

nigelj@156,

You are correct if you confine your parameters to the short term. Over the long haul, that is not the case, as shown in the same Figure 2.

The same is true of the heat wave index depicted in Figure 1. A short term increase, but a larger long term decrease. Are we talking weather or climate here? I would argue that the long term climatic trend has not changed with regards to high temperatures or heat waves, but has changed with regards to nightly low temperatures.

Several other cities show the same trend. Those were just two examples to placate Hank, who has selective citation syndrome.

KM 159,

Good exposition overall, but you slipped a decimal point–the amount of water vapor in the air is 1.27 x 10^16 kg, not 10^17.

Dan H @160, the very long term trend in figure one is not the point. It clearly shows an increasing trend since 1980 – 2018 which is pretty long term, and approximately consistent with the global warming trend, thus showing a reasonable correlation between warming and heatwaves.

Your own source material shows an increase in high temperatures during the day. You have presented no sensible ‘argument’ to believe those are wrong. You cant ignore this and selectively focus just on night time temperatures.

Your arguments about heatwaves are flat wrong. I have shown you research papers showing an increase in the numbers of heatwaves in America. You haven’t been able to refute these.

What other cities? What proportion is this of all cities? (and with proof please)

Is this all the best you have Dan? You have nothing!

Dan, re who has selective citation syndrome.

I think you’ll find that’s Universal Norm aka a Default Position. :-)

We all do it because it’s normal. There are limits to citations refs etc. Besides the extent and the specifics of those references do not necessarily lead to a change of opinion anyway. Meaning and comprehension are more complex than a citation to data or conclusions in a paper / article etc.

Besides that, there is never universal agreement on anyone’s Research / Science Paper – peer reviewed or not is irrelevant to this truism fact. The other universal is it’s easier to find hens teeth than it is someone to have an open-minded genuine dialogue or a discussion in good faith while maintaining an even keel. Being aware that’s even an issue worth addressing is even rarer. Cheers

Give the world the best you have and you’ll get kicked in the teeth.

Give the world the best you have anyway.

http://www.paradoxicalcommandments.com/

nigelj,

That is rather brazen of you to claim that my references are wrong and yours are correct. From all I can tell, our big difference is in our definition of “long-term.” I contend that long-term (with regards to AGW) refers to a period of a century or more. Your 30-year time period could be define as medium-term at best, but not long-term. The century-long epa dataset shows an increase in daily highs for the first 20 years, then a decrease over the next 40, followed by an increase over the past 40 (roughly), with no overall trend. Conversely, the increased in hot daily lows shows a smaller increase over the early years, followed by much higher increase in recent years.

What is not evident from this dataset, but is exemplified in the heat wave index, is that most of these new highs occurred in the colder months, not in summer. Hence, heat waves decreased over the long term, and have shown no trend over the short term. Perhaps this reference may help to enlighten:

https://science2017.globalchange.gov/chapter/6/

Note in particular table 6.2, which details changes in the hottest and coldest days of the year over the past 30 years. Every region of the U.S. has experienced an increase in the coldest days, ranging from 1.1F to 4.8F, averaging 3.3F. Meanwhile, all regions but the desert southwest have witness a decrease in the hottest day, ranging from -0.2F to -2.2F, averaging -0.9F. Figure 6.3 shows the change over the past century. The coldest days increased by 6F, while the hottest days increased by 2F over the first 40 years, then decreased by 2F over the next 40, and have been relatively flat since. Heat waves are detailed in 6.4, showing a large increase from the beginning of the 20th century through the mid 1930s, followed by a larger decrease through the mid 70s, and a smaller increase to date, such that heat waves remain below the level seen at the start of the 20th century.

From the reference, “As with warm daily temperatures, heat wave magnitude reached a maximum in the 1930s. The frequency of intense heat waves (4-day, 1-in-5 year events) has generally increased since the 1960s in most regions except the Midwest and the Great Plains. , Since the early 1980s (Figure 6.4), there is suggestive evidence of a slight increase in the intensity of heat waves nationwide.”

Once again, the devil is in the details.

#161–Thanks, Barton; that’s a type of error I’m prone to (deep layers of mathematical ‘rust’; many relatively simple calculational tasks just aren’t a regular part of my life).

159 – Kevin

Thanks for the excellent explanation!

Dan H @164 thank you for finally admitting heatwaves have increased in recent decades in America. The research I posted appears to find slightly more heatwaves, possibly the truth is between the two somewhere.

The fact that the recent increase in numbers of heatwaves in America is less than in the well known dustbowl period is of little comfort. Given heatwaves have increased in recent decades and are related to agw climate change according to the IPCC, they are very likely going to become even more frequent and / or intense. Isn’t America experiencing one at the moment? :)

Nuclear has been brought up several times. Sure after all the digging and refining it doesn’t release CO2. However uranium hexafliuoride gas molecule is 23,900 times the effect of one molecule of carbon-dioxide. Digging them up does cost and continues to cost. Storage facilities for the waste don’t look like they could last but maybe a thousand years if I was generous. Some need a million years to decay to lead. (We have no experience in long term storage. The costs are so great that only govt’s back then. I’m all for letting the market decide with nuclear power.

Cost overruns are common with building them and maintaining them. With the money wasted you could furnish solar to an entire state. No one will want to assault a solar array unlike a nuke plant. Drop it as a too expensive, too dangerous and too much work to protect us from its waste.

#166, KIA–

Glad it was helpful!

Yes I also say let the market decide regarding nuclear power, so generating companies and maybe local communities decide whether to build nuclear power or other forms of renewable energy. Currently the market is not enthusiastic about nuclear power in America, because its too problematic

I don’t think Governments should push nuclear power one way or the other. Governments role is simply to promote low carbon electricity generation as a whole.

Carrie: do not necessarily lead to a change in opinion

AB: Very little changes a typical human’s opinion except the devastation or death of a loved one. We need orders of magnitude more death amongst rich families.

(Which places me ever so close to “terrorists” ::shudder::)

Nigelj,

America experiences heat waves every sumner. That is nothing new. My admission about heat waves, is that they are increasing if your definition is based on summer nighttime low temperatures. If the basis is summer daytime high temperatures, then they are not. Hence, people can claim either, based on their preferred definition. This is likely related to agw, as theory predicts increases in the coldest temperatures, but not the hottest. The decrease in summer high temperatures is not incaparable with agw. The fact that high temperatures remain below the hotter previous summers is comforting. This is an indication that increased mortality is not evident from agw.

nigelj

Yes, you are correct on skyscrapers needing AC in their current configuration. They could probably be coated with that nano-particle paint that makes sunlit surfaces cooler than ambient, but that stuff is expensive.

Your comment on heatwaves: “Isn’t America experiencing one at the moment?”

Absolutely right – it’s late July and if we weren’t having one it would be highly unusual. We can expect heatwaves to occur thru mid September at least in various parts of the country – not unusual.

July 22, 09-13 UTC, weather station OIZJ (Jask, Iran) reported temp 35C

(95F) dew point 31C (88F), making a heat index of 57C/134F.

Dan H. @172

“My admission about heat waves, is that they are increasing if your definition is based on summer nighttime low temperatures. ”

I don’t accept your definition. With respect it’s some sort of personal definition you have come up with that doesn’t make sense to me, (other than to say it makes nights even more uncomfortable in some places).

The normal definition of heatwaves is quite different. Heatwaves on wikipedia discusses a range of common accepted science based definitions, and with the common feature of being based on ‘average’ daily temperatures, not night time temperatures. For example : “A definition based on Frich et al.’s Heat Wave Duration Index is that a heat wave occurs when the daily maximum temperature of more than five consecutive days exceeds the average maximum temperature by 5 °C (9 °F), the normal period being 1961–1990.”

“If the basis is summer daytime high temperatures, then they are not. ”

Nobody is suggesting this. Averages above baselines are used.

“This is likely related to agw, as theory predicts increases in the coldest temperatures, but not the hottest. ”

I don’t think this is correct. Climate change modelling predicts night time minumum temperatures will increase, but also that daily maximums will increase as well, just not quite as much. And reality is confirming all this. Here is the IPCC report talking about projections below. The IPCC report also discusses recent trends of increasing daily maximumns and night time minimums etc, and a google finds plenty of examples.

https://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/ch10s10-es-2-temperature-extremes.html

https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/joc.4761

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3878/j.issn.1674-2834.12.0106

“The decrease in summer high temperatures is not incaparable with agw. The fact that high temperatures remain below the hotter previous summers is comforting. This is an indication that increased mortality is not evident from agw.”

With respect this is simply wrong and is convoluted reasoning. Figure two in the EPA article you posted shows an increase in the area of the USA with unusually hot temperatures in approximately the last five decades. Figure 6 shows and increase in Record Daily High Temperatures in the Contiguous 48 States, 1950–2009 . To quote the article :Nationwide, unusually hot summer days (highs) have become more common over the last few decades (see Figure 2). The occurrence of unusually hot summer nights (lows) has increased at an even faster rate. This trend indicates less “cooling off” at night.

This is all clearly related to the modern global warming period from approximately 1970 – 2018, so shows agw is associated with essentially more heatwaves and thus more mortality. The increased frequency of heatwaves and general spiking high temperatures in the 1930’s period was clearly mainly (but not entirely ) related to natural climate change and unusual local weather events, but was of relatively short duration. I also don’t understand how it all gives you ‘comfort’ because heatwaves and drought conditions in the 1930s were a killer. The difference is instead of these being very rare events, we are at risk of making them very common!

In addition, climate change is increasing daily maximum temperatures, (as far as I can tell) but this is not the only factor to consider with heatwaves, or even the main one. The principal predictions are that heatwave events (where a definied number of days are above a certain defined temperature) are predicted to increase in frequency and already are in America and many other countries, based on the research paper I posted and your own link! Heatwaves killed people in the past, so more of them will logically kill more people. They are also predicted to last longer adding to the problem.

It’s foolish and now indefensible to deny theres a heatwave problem related to climate change, both during the day and night. America is also not actually the only country in the world that matters and the problem will be more acute in Asia, the middle east and Africa especially as it starts to combine with humid conditions. The evidence is monumental and it will only get worse while we continue to burn fossil fuels.

Nigelj,

Your logic that since heatwaves killed people in the past that they will logically kill more in the future is simplistic and not supported. Several studies, including the few I reference here, show that daily high temperature has a greater effect on mortality than average temperature or heat wave duration. Other factors, mainly socio-economic, latitude, health, and age, were large contributors, making generalizations difficult.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3955771/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3324776/

https://jech.bmj.com/content/jech/64/9/753.full.pdf

https://www.nature.com/articles/srep00830

It is still foolish to think that just because average temperatures are increasing, that this means that every aspect of temperature is increasing. As the studies I presented show, daily summertime high temperatures are not increasing, and in many instances are falling (although not significantly). Since summertime high temperatures are the greater factor in heat wave mortality, the problem you claim is increasing, may not be a problem after all. Oftentimes, generalizations are not sufficient to estimate outcomes, and specifics become more important.

Dan H: America experiences heat waves every sumner. That is nothing new.

AB: Heat waves in the US, per Wiki:

1901 1936 1950s (Note: massive solar maximum) 1983 1988 1995 1999 2000 2001 2002 2006 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2015 2016 2017 2018

Heat waves were rare in the US before 1983, and it is only in this century that they’ve shifted towards becoming an every-summer thing.

Ahhh, the joys of shifting baselines. Dan (and most everybody) simply believes that what is always was. (There ya go, Killian: an example of human nature!)

It keeps getting worse for Jask, Iran (weather station OIZJ) On July 27,

09 UTC, they reported temperature 38C (100F), dew point 33C (91F)! Heat index 68C/154F.

Al,

I would not use Wiki has your evidence comparing recent events to past history. It has a history over-emphasizing recent events and under-reported past events. Notably missing from your list is the disastrous 1896 heat wave, which killed an estimated 1500 people in New York City. Also missing is the 1911 heat wave, which has been claimed to be the worst disaster in New England, killing an estimated 2000. What about 1934? 1911? 1918?

You Wikipedia article clearly states that it was a partial list. Not only that, there are years listed with no heat wave refernces, like 2009 and 2013. I guess the old saying that I read it on the internet so it must be true, is still alive and well.

Dan H @ 176

Your claim that summertime high temperature have not increased in America is wrong. Many states show an increase and only a very small number show a cooling trend as below

http://www.climatecentral.org/gallery/maps/summer-minimum-maximum-temperatures

However you are incorrect to think this is the “only” factor to consider in heatwaves. As I have already stated, the frequency of heatwaves in America of typical temperature profile common for centuries has increased in recent decades, so clearly more fatalities occur in sum total. Your quoted studies do not claim changes to temperature profiles are the only factor to consider.

https://science2017.globalchange.gov/chapter/6/

https://www.skepticalscience.com/heatwaves-past-global-warming-climate-change.htm

https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00575.1

Nigelj,

My claim is not wrong. It just different from yours. You are using data of the shorter term, from the 1970s to date, whereas I am using long term data from the early 20th century. I would argue that cherry-picking data from a rather cold decade is the poorer choice for comparison. You also seem to be backtracking to include all summer temperatures, whereas the argument centered around maximum summer temperatures, which have shown a widespread decrease, even over your short-term time frame.

I did not say that maximum temperatures was the “only” factor to consider. Rather that the medical research shows that the temperature maximum is the major factor to consider; higher low temperatures and heat wave duration were relevant, but lesser factors. Age, socio-economic, and health was other factors. Consequently, past heat waves resulted in greater fatalities.

“The excess mortality with high temperatures observed between 1900 and 1948 was substantially reduced between 1973 and 2006”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4096340/

The death rate in the U.S. due to extreme heat declined 17% from the 1979-92 period to 1993-2006.

http://www.jpands.org/vol14no4/goklany.pdf

This trend is not isolated to the U.S. Australia, in which high temperatures are the greatest extreme weather threat, has seen a decrease in it death rate since 1907.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901114000999

“Extreme heatwaves could make the north China plain uninhabitable in places if climate change is not curbed – it is home to 400m people and vital to China’s food production”

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/jul/31/chinas-most-populous-area-could-be-uninhabitable-by-end-of-century

But the climate denialists don’t care. As long as America is ok, that’s all that matters apparently.

#181, Dan H–

What a strange thing to say! Apparently, the ‘rather cold’ decade is the 1970s, a decade that was indeed cold with respect to every decade that followed. But in the longer term perpective Dan lays out, it’s not ‘rather cold’ at all, but pretty much in the middle–the only prior decade that was warmer was the 1940s. I did a quick and dirty illustration at woodfortrees:

http://woodfortrees.org/plot/gistemp/from:1900/mean:13/plot/gistemp/from:1900/to:1910/trend:120/plot/gistemp/from:1910/to:1920/trend/plot/gistemp/from:1920/to:1930/trend/plot/gistemp/from:1930/to:1940/trend/plot/gistemp/from:1940/to:1950/trend/plot/gistemp/from:1950/to:1960/trend/plot/gistemp/from:1960/to:1970/trend/plot/gistemp/from:1970/to:1980/trend

(You can eyeball the averages reasonably well from the decadal linear trends shown for the decades up to and including the 70s, but if you want a more precise reading, the OLS tool reports the decadal mean, and you can see that by clicking on the ‘raw data’ link.)

So there’s an incoherency there: if you follow Dan’s apparent logic, you’d think that the 70s should cooler, not warmer, than the early 20th century. But not so.

One issue, I expect, is US versus global data; it’s well-known that the 30s were very warm in the US, and if I’m not mistaken–I’m speaking off the top of my head here–some of the epidemiological studies in question were exclusively American in scope.

But I expect that an even bigger issue is economic, social and technological change. People were very often not living the same lives at all in 1970, or 80, or 90, that their parents and grandparents had been in 1900, or 1910. Two terms in particular come to mind in the North American context: 1) agricultural labor, and 2) air conditioning.

So I would argue that if you are going to compare heat mortality figures from the early 20th century with those from the early 21st century, you have a really, really hard job in hand if you are going to disentangle all the (potential) causative factors, and you are going to have to be really, really meticulous about all the technical details–data homogeneity, scoping, baselines, etc., etc. You might be better off looking at the shorter term data after all.

Dan H @181

“You are using data of the shorter term, from the 1970s to date, whereas I am using long term data from the early 20th century. I would argue that cherry-picking data from a rather cold decade is the poorer choice for comparison.”

I agree with KM you aren’t making much sense here! I would only add I’m interested in the modern post 1970s agw global warming trend, and it’s relationship to heatwaves and what this portends for the future. America’s dust bowl period is of only historical interest (although I know it was terrible for you guys, and I do appreciate this).

“You also seem to be backtracking to include all summer temperatures, whereas the argument centered around maximum summer temperatures, which have shown a widespread decrease, even over your short-term time frame.”

My link did not describe all summer temperatures. It described “summertime high temperatures” which I believe are maximum temperatures. You have not shown me a widespread decrease in summertime maximum temperatures, just an example of three cities, which is less than 1% of the land area of America and may simply reflect local circumstances.

“I did not say that maximum temperatures was the “only” factor to consider. Rather that the medical research shows that the temperature maximum is the major factor to consider; higher low temperatures and heat wave duration were relevant, but lesser factors”

The research you posted previously did not in the main refer to “maximum temperature peak” during heatwaves, and whether climate change is increasing that temperature. It only said that the high temperatures of the type that are typical in heatwaves were an important factor to consider, and compared heatwaves to cold periods. And climate change will certainly make heatwaves hotter on average.

In other words you do not need a very high peaking temperature before fatalities and problems occur, you just require several days of unusually high temperatures above the norm. I’m sure you appreciate this?

I agree they did say duration was less of a factor than temperatures.However increasing night time temperatures are actually pretty important, as it can start to cause severe insomnia. Not everyone can afford air conditioning.

But why do you persistently ignore the frequency (numbers) of heatwaves? Heatwaves with ‘unexceptional’ or typical temperature profiles still cause fatalities and other problems obviously, and climate change is causing more heatwaves in America and also globally, as I have shown in links to two separate research studies. You dont need “hotter heatwaves” for more heatwaves to be a problem. Why are you ignoring this obvious thing?

But make no mistake climate change will cause more intense heatwaves as well.

“The excess mortality with high temperatures observed between 1900 and 1948 was substantially reduced between 1973 and 2006”

Yes no doubt medical advances and so on helped. But there are clearly still multiple fatalities and illness during recent heatwaves, and you forget lost work productivity, and problems for agriculture that are not always easy to mitigate. All this will be made worse as climate change causes 1) more heatwaves and 2) hotter heatwaves and 3) longer heatwaves.

It would be stupid to believe we can find simple solutions to increasing problems of this type.

Dan H @182, just to clarify by “climate change is causing more heatwaves in America and also globally, as I have shown in links to two separate research studies.” I obviously meant a larger number of heatwaves compared to earlier decades.

Kevin – I think the 1970s were considerably warmer than 20th century decades that precedent them.

1901 to 1981

data

The cited Martens 98′ study “global climate change is likely to lead to a reduction in mortality rates”, coincident-ed with Budyko’s conclusion, “increased incidence of heat-stroke in the aged and young population in summer seasons.”

During the 2003 heatwave high ground level ozone was also reported.

Nigelj,

I will agree that there are many more causative factors contributing to the mortality figures than just temperature.

If you truly believe that the 70s were warmer than the earlier years of the 20th century, then you should have no issues using data going back 100 years, instead of only 40. I question your insistence on making conclusions based on shorter term data, when the longer term is available. In that case, should not the long term just be a continuation of the short term? The fact that it is not, should make one wonder why there is a difference. Specifically, why were the highest maximum temperatures recorded in the earlier years, and not in the most recent years?

https://www.dw.com/en/the-heat-wave-goes-on-and-on/g-44953047

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/04/world/europe/europe-heat-wave.html

JCH, #186–

The 70s were considerably warmer than preceding 20th-century decades–barring the 1940s. That’s what I was trying (and possibly failing) to point out. I don’t include the 40’s in the ‘considerably’, though, as your plot shows the 40’s as a mere ~4/1000s of a degree cooler than the 70s. So, 70s warmer, yes, but not ‘considerably.’

I confess to having erred a bit by doing the analysis starting with the “00” year–and if you are so cavalier as to do that, it turns out that the 40s were warmer than the 70s by an even more ‘mere’ thousandth or so:

http://www.woodfortrees.org/plot/gistemp/from:1900/to:1990/compress:120

Now, I believe your way is correct, as if I’m not mistaken, the decade properly starts with the “01” year, not the “00” year. (That is why the Clarke/Kubrick classic isn’t called “2000: A Space Odyssey”.)

Either way, my point to Dan isn’t affected. (And in broad terms, the 40s and 70s were pretty well comparable in terms of MST. I wouldn’t be surprised if you were to see the rankings flip-flop if you ran the analysis with HADCRU or whatever the NCEI are calling their data these days.)

P.S. Thanks for a side benefit–I’d been looking for a way to calculate decadal (or other) averages on WFT, but it never occurred to me that the description for that would be ‘compress’–though in retrospect it seems logical enough. So, another trick learned. What’s that about old dogs?

#190, Hank–

Yeah, when they are helicoptering water to cows, there is definitely something wrong with the picture.

Dan B @188

Ok thank’s for admitting many things contribute to heatwave problems, not just maximum temperatures.

Perhaps we are talking at cross purposes on temperatures. A common internet problem. This data certainly shows average surface temperatures are higher in America in recent decades than in the early part of last century.

https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-us-and-global-temperature

As to your summertime only urban high temperatures, I dont live in America and I don’t have all day to research the issue, so I’m not going to dispute what you say.

However I think the real problem is 1) higher frequency of heatwaves is obviously a big problem and 2) It’s looking very probable that climate change will soon destroy most of those old summertime temperature records.

I mean seriously also look at the northern hemisphere heatwave currently. If that sort of thing becomes frequent, we have a huge problem.

Kevin McKinney

“Yeah, when they are helicoptering water to cows, there is definitely something wrong with the picture.”

It gets worse. In France they are feeding ice cold fruit and drinks to animals in the zoo, and have closed down a couple of nuclear reactors in case the river gets too warm and starts killing off all the fish life.

Nigelj,

I think we are starting to understand each other better. Part of the issue is that the term heat wave is rather nebulous, as it does not have a concise definition, and means different things to different people (a heat wave in London does not equate to a heat wave in Phoenix, etc.).

I will agree that due to socio-economic changes, heat waves do not appear to have the same devastating impact that they had in the past. Different medical journals have published research into the health affects associated with heat waves. Some state that the magnitude of the days heat is most important, other the lack of cool nights, some a combination of heat and humidity, and still other the length of the heatwave. You get no argument from me that heat waves are a health problem. Currently, they are not as big a problem as other weather issues though. How they change in the future is uncertain. They may continue to increase, as they have since the 70s. If they reach the magnitude that occurred in the 30s, then we may have a huge problem. I am not convinced that they will. If (notice I said if) the maximum heat wave temperature is the major factor in death and illness due to heat waves, then current trends will not result in serious problems. I think we have reached an agreement that while average temperatures have increased, and average summertime temperatures have increased, this is due largely to higher nighttime lows, as summertime high temperatures have actually decreased slightly.

You can check temperature records in the U.S. easily:

https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cdo-web/datatools/records

Comparing recent years to some past yields the following data (averaged per 1000 reporting stations):

Month Year High Max High Min

Jan. 1936 4.6 6.7

1940 4.4 8.8

2017 16.3 27.6

2018 14.0 16.8

Feb. 1936 4.1 7.9

1940 8.0 12.8

2017 56.6 52.2

2018 29.2 35.3

July 1936 74.1 41.6

Nigelj,

I think we are starting to understand each other better. Part of the issue is that the term heat wave is rather nebulous, as it does not have a concise definition, and means different things to different people (a heat wave in London does not equate to a heat wave in Phoenix, etc.).

I will agree that due to socio-economic changes, heat waves do not appear to have the same devastating impact that they had in the past. Different medical journals have published research into the health affects associated with heat waves. Some state that the magnitude of the days heat is most important, other the lack of cool nights, some a combination of heat and humidity, and still other the length of the heatwave. You get no argument from me that heat waves are a health problem. Currently, they are not as big a problem as other weather issues though. How they change in the future is uncertain. They may continue to increase, as they have since the 70s. If they reach the magnitude that occurred in the 30s, then we may have a huge problem. I am not convinced that they will. If (notice I said if) the maximum heat wave temperature is the major factor in death and illness due to heat waves, then current trends will not result in serious problems. I think we have reached an agreement that while average temperatures have increased, and average summertime temperatures have increased, this is due largely to higher nighttime lows, as summertime high temperatures have actually decreased slightly.

You can check temperature records in the U.S. easily:

https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cdo-web/datatools/records

Comparing recent years to some past yields the following data (averaged per 1000 reporting stations):

Month Year High Max High Min

Jan. 1934 20.9 20.5

1936 4.6 6.7

1940 4.4 8.8

1954 3.5 9.7

2006 26.0 22.3

2017 16.3 27.6

2018 14.0 16.8

July 1934 50.4 46.4

1936 74.1 41.6

1940 17.7 16.7

1954 30.0 19.0

2006 20.0 25.0

2017 7.1 11.8

2018 11.5 19.7

“Specifically, why were the highest maximum temperatures recorded in the earlier years, and not in the most recent years?”

Well, one reason could be a change in equipment, and I am not sure those Tmax observations are corrected for this. As I understand it, the change from Stevenson screen-based systems to automated MMTS systems introduces on average a 0.5 degree cooling bias in Tmax. Corrections are made when climate trends are determined, but not sure these are also made when looking at records. But maybe they are. Anyone know?

Marco, #197–

The data Dan B. was using in his more recent posts–and I can’t tell if that’s the same data relevant to the quote you cite–is raw data. On the same NCEI records page he cites in connection with those inscrutable tables he offers up, you find this:

“These data are raw and have not been assessed for the effects of changing station instrumentation and time of observation.”

So your suggestion may be the answer, or part of it.

Here’s the link again:

https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cdo-web/datatools/records

Can’t see how that relates to the tables in #195-6, though.

Dan @195

Thank’s, but I cant make much sense of your figures because they are for just one or two months, but like I said I’m not going to argue with you about daily summertime temperature trends.

So yes ok summertime maximum temperatures have not increased beyond the 1930’s in America and may have a falling trend. This may however be temporary.

However its well known night time temperatures are increasing and so you are right there. This could be even more of a health concern anyway, because I was just reading an article where very hot nights mean our organ’s dont shut down properly to recuperate, and it can cause serious health issues, and of course hot nights also cause insomnia, and recent health research indicates this is a much larger problem for health than previously realised.

However I still dont think you are entirely getting this. The ‘frequency’ of heatwaves has already increased due to climate change, so we are having more problems to deal with. They dont have to be absolute record setting heatwaves to be a problem. For example while Greece is currently getting record temperatures the heatwaves in France is more moderate, but is still a huge problem for people and crops etc. So I mean as these become more frequent then it is still a costly and debilitating thing for society to deal with. I mean this should be really obvious. But anyway, thanks for interesting, and non shouty discussion, but I’m finished with it for now.

Nigelj @ 199,

Yes, the figures were intended to be just for the hottest and coldest months. That was to emphasize that high temperatures have been increasing in the cold month, but not in the hot months (they looked a lot nicer when I spaced them out, before they got contracted). I am not sure that the trend is temporary, as the 30s had more record summer highs than the 50s, which had more than the 80s, which had more than today.

There has been an on-going discussion about which parameters of heat waves are most detrimental. Some contend it is the hotter days, some the warmer nights, and still others the length of the heat wave. All of these are concerns, but if one stands out as a major concern, then its effects should be emphasized.

Once again, the frequency has increased over the shorter term, since the 60s and 70s. The following research shows that (in the U.S.) heat waves were most frequent in the 1930s. The 2000s were a distant second, followed closely by the 10s, 50s, and 20s. Heat waves were least frequent in the 1960s, followed by the 70s, so any trend starting from that time frame will naturally show an increase.

https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00066.1

I am getting this. If the trend over the shorter term is more significant than the longer term, then this will likely become a graver health concern. Similarly, if warmer nights are more important than hotter days, then that is also a grave concern. Research to date is inconclusive.

I thank you also for this discussion, especially the gentlemanly manner in which it was conducted. We may not agree for now, but I welcome future talks, especially as more definitive research is performed.

Yes, it is time to move on to other threads. Good day.