Some of you that follow my twitter account will have already seen this, but there was a particularly amusing episode of Q&A on Australian TV that pitted Prof. Brian Cox against a newly-elected politician who is known for his somewhat fringe climate ‘contrarian’ views. The resulting exchanges were fun:

[Read more…] about Australian silliness and July temperature records

Archives for 2016

Unforced variations: Aug 2016

Sorry for the low rate of posts this summer. Lots of offline life going on. ;-)

Meantime, this paper by Hourdin et al on climate model tuning is very interesting and harks back to the FAQ we did on climate models a few years ago (Part I, Part II). Maybe it’s worth doing an update?

Some of you might also have seen some of the discussion of record temperatures in the first half of 2016. The model-observation comparison including the estimates for 2016 are below:

It seems like the hiatus hiatus will continue…

Unforced variations: July 2016

A week is a long time in politics climate science: Nonsense debunked in WaPo, begininngs of recovery in the ozone hole, revisiting the instrumental record constraints on climate sensitivity…

Lots of lessons there.

Usual rules apply.

Boomerangs versus Javelins: The Impact of Polarization on Climate Change Communication

Guest commentary by Jack Zhou, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University

For advocates of climate change action, communication on the issue has often meant “finding the right message” that will spur their audience to action and convince skeptics to change their minds. This is the notion that simply connecting climate change to the right issue domains or symbols will cut through the political gridlock on the issue. The difficulty then lies with finding these magic bullet messages, figuring out if they talk about climate change in the context of with national security or polar bears or passing down a clean environment to future generations.

On highly polarized issues like climate change, however, communicating across the aisle may be more difficult than simply finding the right message. Here, the worst case scenario is not simply a message failing to land and sending you back to the drawing board. Instead, any message that your audience disagrees with may polarize that audience even further in their skepticism, leaving you in a worse position than you began. As climate change has become an increasingly partisan issue in American politics, this means that convincing Republicans to reject the party line of climate skepticism may be easier said than done.

[Read more…] about Boomerangs versus Javelins: The Impact of Polarization on Climate Change Communication

Unforced Variations: June 2016

Scientists getting organized to help readers sort fact from fiction in climate change media coverage

Guest post by Emmanuel Vincent

While 2016 is on track to easily surpass 2015 as the warmest year on record, some headlines, in otherwise prestigious news outlets, are still claiming that “2015 Was Not Even Close To Hottest Year On Record” (Forbes, Jan 2016) or that the “Planet is not overheating…” (The Times of London, Feb 2016). Media misrepresentation confuses the public and prevents our policy makers from developing a well-informed perspective, and making evidence-based decisions.

Professor Lord Krebs recently argued in an opinion piece in The Conversation that “accurate reporting of science matters” and that it is part of scientists’ professional duty to “challenge poor media reporting on climate change”. He concluded that “if enough [scientists] do so regularly, [science reporting] will improve – to the benefit of scientists, the public and indeed journalism itself.”

This is precisely what a new project called Climate Feedback is doing: giving hundreds of scientists around the world the opportunity to not only challenge unscientific reporting of climate change, but also to highlight and support accurate science journalism.

Do regional climate models add value compared to global models?

Global climate models (GCM) are designed to simulate earth’s climate over the entire planet, but they have a limitation when it comes to describing local details due to heavy computational demands. There is a nice TED talk by Gavin that explains how climate models work.

We need to apply downscaling to compute the local details. Downscaling may be done through empirical-statistical downscaling (ESD) or regional climate models (RCMs) with a much finer grid. Both take the crude (low-resolution) solution provided by the GCMs and include finer topographical details (boundary conditions) to calculate more detailed information. However, does more details translate to a better representation of the world?

The question of “added value” was an important topic at the International Conference on Regional Climate conference hosted by CORDEX of the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP). The take-home message was mixed on whether RCMs provide a better description of local climatic conditions than the coarser GCMs.

[Read more…] about Do regional climate models add value compared to global models?

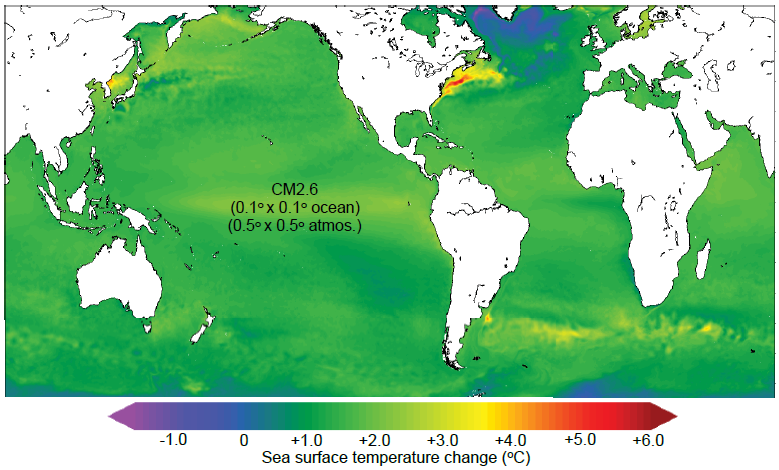

AMOC slowdown: Connecting the dots

I want to revisit a fascinating study that recently came from (mainly) the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Lab in Princeton. It looks at the response of the Atlantic Ocean circulation to global warming, in the highest model resolution that I have seen so far. That is in the CM2.6 coupled climate model, with 0.1° x 0.1° degrees ocean resolution, roughly 10km x 10km. Here is a really cool animation.

When this model is run with a standard, idealised global warming scenario you get the following result for global sea surface temperature changes.

Fig. 1. Sea surface temperature change after doubling of atmospheric CO2 concentration in a scenario where CO2 increases by 1% every year. From Saba et al. 2016.

Recycling Carbon?

Guest commentary by Tony Patt, ETH Zürich

This morning I was doing my standard reading of the New York Times, which is generally on the good side with climate reporting, and saw the same old thing: an article about a potential solution, which just got the story wrong, at least incomplete. The particular article was about new technologies for converting CO2 into liquid fuels. These could be important if they are coupled with air capture of CO2, and if the energy that fuels them is renewable: this could be the only realistic way of producing large quantities of liquid fuel with no net CO2 emissions, large enough (for example) to supply the aviation sector. But the article suggested that this technology could make coal-fired power plants sustainable, because it would recycle the carbon. Of course that is wrong: to achieve the 2°C target we need to reduce the carbon intensity of the energy system by 100% in about 50 years, and yet the absolute best that a one-time recycling of carbon can do is to reduce the carbon intensity of the associated systems by 50%.

The fact is, there is a huge amount of uncritical, often misleading media coverage of the technological pathways and government policies for climate mitigation. As with the above story, the most common are those suggesting that approaches that result in a marginal reduction of emissions will solve the problem, and fail to ask whether those approaches also help us on the pathway towards 100% emissions reduction, or whether they take us down a dead-end that stops well short of 100%. There are also countless articles suggesting that the one key policy instrument that we need to solve the problem is a carbon tax or cap-and-trade market. We know, from two decades of social-science research, that these instruments do work to bring about marginal reductions in emissions, largely by stimulating improvements in efficiency. We also know that, at least so far, they have done virtually nothing to stimulate investment in the more sweeping changes in energy infrastructure that are needed to eliminate reliance on fossil fuels as the backbone of our system, and hence reduce emissions by 100%. We also know that other policy instruments have worked to stimulate these kinds of changes, at least to a limited extent. One thing we don’t know is what combination of policies could work to bring about the changes fast enough in the future. That is why this is an area of vigorous social science research. Just as there are large uncertainties in the climate system, there are large uncertainties in the climate solution system, and misreporting on these uncertainties can easily mislead us.

It’s fantastic that web sites like Real Climate and Climate Feedback re out there to clear some of the popular misconceptions about how the climate system functions. But if we care about actually solving the problem of climate change, then we also need to work continuously to clear the misconceptions, arising every day, about the strategies to take us there.

Anthony Patt is professor at the ETH in Zurich; his research focuses on climate policy

Comparing models to the satellite datasets

How should one make graphics that appropriately compare models and observations? There are basically two key points (explored in more depth here) – comparisons should be ‘like with like’, and different sources of uncertainty should be clear, whether uncertainties are related to ‘weather’ and/or structural uncertainty in either the observations or the models. There are unfortunately many graphics going around that fail to do this properly, and some prominent ones are associated with satellite temperatures made by John Christy. This post explains exactly why these graphs are misleading and how more honest presentations of the comparison allow for more informed discussions of why and how these records are changing and differ from models.

[Read more…] about Comparing models to the satellite datasets