How has global sea level changed in the past millennia? And how will it change in this century and in the coming millennia? What part do humans play? Several new papers provide new insights.

2500 years of past sea level variations

This week, a paper will appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) with the first global statistical analysis of numerous individual studies of the history of sea level over the last 2500 years (Kopp et al. 2016 – I am one of the authors). Such data on past sea level changes before the start of tide gauge measurements can be obtained from drill cores in coastal sediments. By now there are enough local data curves from different parts of the world to create a global sea level curve.

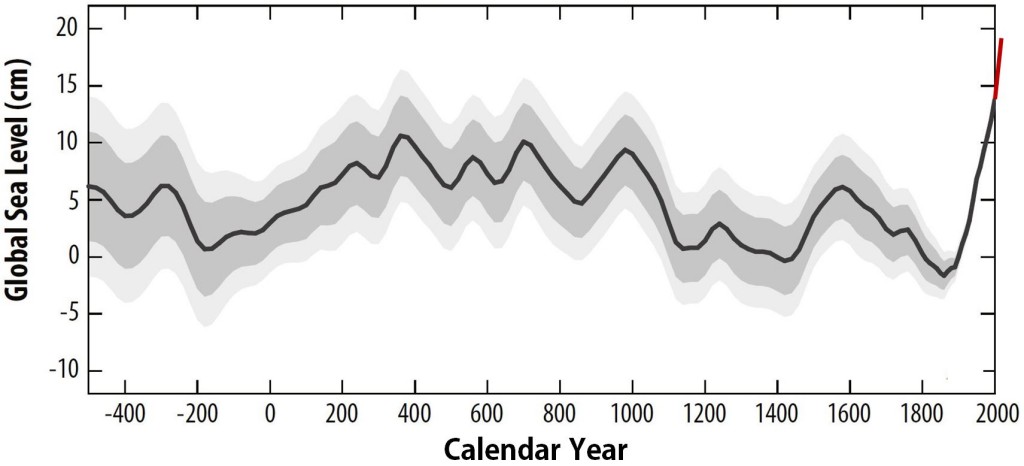

Let’s right away look at the main result. The new global sea level history looks like this:

Fig. 1 Reconstruction of the global sea-level evolution based on proxy data from different parts of the world. The red line at the end (not included in the paper) illustrates the further global increase since 2000 by 5-6 cm from satellite data.

To understand this curve we need to know one thing. There is a remaining uncertainty in the linear trend over the whole period. This is because in many places of the world slow processes, especially continuing land uplift or subsidence after the end of the last Ice Age, cause a sea-level trend uncertainty (because land subsidence is not the same as sea level rise, this needs to be subtracted). It is therefore the fluctuations around the linear trend which are the most robust aspect of these data. The uncertainty in the trend is small, only 0.2 mm/year (the current sea level rise is 3 mm/year). But even a small steady trend of 0.2 mm/year amounts to half a meter during 2500 years. For the graph above, this means that the correct curve could be “tilted” a little to the left or right. This would, for example, change the relative global sea level in 2000 compared to the Middle Ages – this relative height does not belong to the robust results, as stated in the paper.

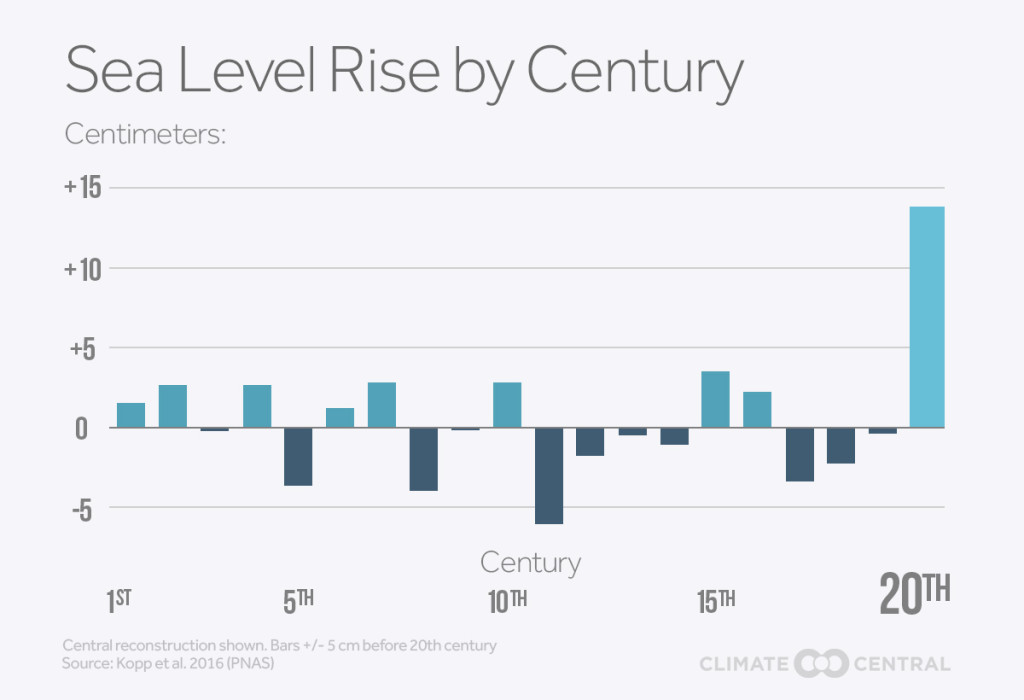

In contrast, a robust result is the fact that sea level has risen more during the 20th century than during any previous century. (This statement is true regardless of an additive trend.) A good way to show this is the following graph.

Fig. 2 Sea-level change during each of the twenty centuries of the Common Era (Graph: Climate Central.)

The fact that the rise in the 20th century is so large is a logical physical consequence of man-made global warming. This is melting continental ice and thus adds extra water to the oceans. In addition, as the sea water warms up it expands. (A new study has also just been published about the size of individual contributions derived from satellite data: Rietbroek et al 2016).

The paleoclimatic data reaching back for millennia can be used to better separate the natural variations in sea level and the human impact. With near-certainty at least half of the rise in the 20th century is caused by humans; possibly all of it. From natural causes alone sea level might also have fallen in the 20th century, instead of the observed rise by close to 15 centimeters.

What will happen in the 21st century?

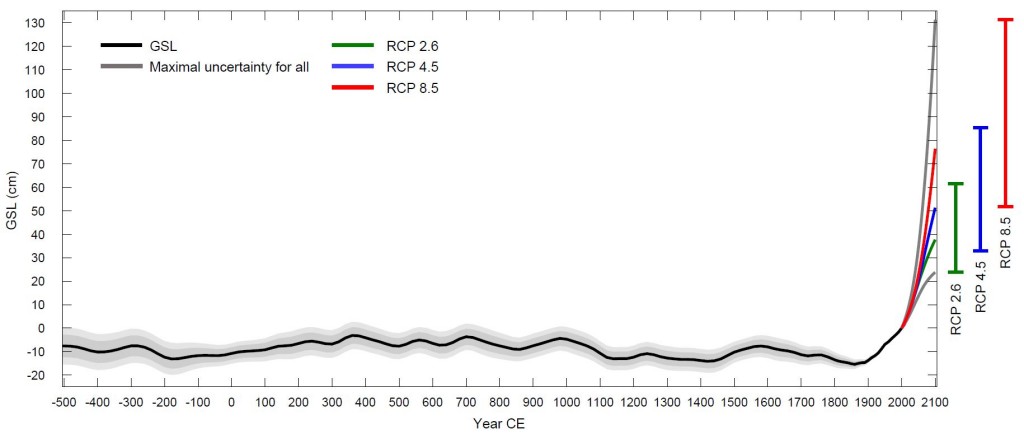

The data from the past can also be used for future projections, using a so-called semi-empirical model calibrated with the historically observed relationship between temperature and sea level. With the new data, this results in a projected increase in the 21st century of 24-131 cm, depending on our emissions and thus on the extent of global warming.

This brings us to a second study, also published this week in PNAS (Mengel et al. 2016). In this paper a new method of sea-level projections is developed. It is not based on complex models, but also on simple semi-empirical equations. But not for sea level as a whole but for the individual causes of sea-level changes: thermal expansion of sea water, melting of glaciers and mass loss of the large ice sheets. These equations are calibrated based on data from the past and then extrapolated to a warmer future. It is a kind of hybrid between the semi-empirical and the process-based approach (favored by the IPCC) to sea-level projections. The following table compares the projections of the various methods.

| Scenario | IPCC 2013 | Kopp 2016 | Mengel 2016 | Horton 2014 |

| RCP 2.6 | 28–60 | 24–61 | 28-56 | 25–70 |

| RCP 4.5 | 35–70 | 33–85 | 37-77 | n.a. |

| RCP 8.5 | 53–97 | 52–131 | 57-131 | 50–150 |

Table 1 Global sea level rise in centimeters over the 21st century according to various studies for different emission scenarios. The first scenario (RCP 2.6) assumes successful climate policies limiting global warming to about 2°C; the last (RCP 8.5), however, unabated emissions and heating by around 5°C. (The ranges indicate the 90 percent confidence intervals except for the IPCC, which only provided a 66 percent confidence interval.)

The final column shows the results of an expert survey among 90 distinguished sea-level researchers (Horton et al. 2014). The projections on the basis of very different data and models thus yield very similar results, which speaks for their robustness. With one important caveat, however: the possibility of ice sheet instability, which for many years has been hanging like a shadow over all sea-level projections. While we have a pretty good handle on melting at the surface of the ice, the physics of the sliding of ice into the ocean is not fully understood and may still bring surprises. I consider it possible that in this way the two big ice sheets may contribute more sea-level rise by 2100 than suggested by the upper end of the ranges estimated by Mengel et al. for the solid ice discharge, which is 15 cm from Greenland and 19 cm from Antarctica. (The biggest contributions to their 131 cm upper end are 52 cm from Greenland surface melt and 45 cm from thermal expansion of ocean water.)

This concern is reinforced strongly by two further new papers, also appearing in PNAS this week, by Gasson et al. and by Levy et al.. These papers look at the stability of the Antarctic Ice Sheet during the early to mid Miocene, between 23 and 14 million years ago. What is most relevant here is the advances in modelling the Antarctic ice sheet by including new mechanisms describing the fracturing of ice shelves and the breakup of large ice cliffs. The improved ice sheet model is able to capture the highly variable Antarctic ice volume during the Miocene; the bad news is that it suggests the Antarctic Ice Sheet can decay more rapidly than previously thought.

Fig. 3 The last 2500 years of sea level together with the projections of Kopp et al. for the 21st century. Future rise will dwarf natural sea-level variations of previous millennia.

Global vs. regional increase

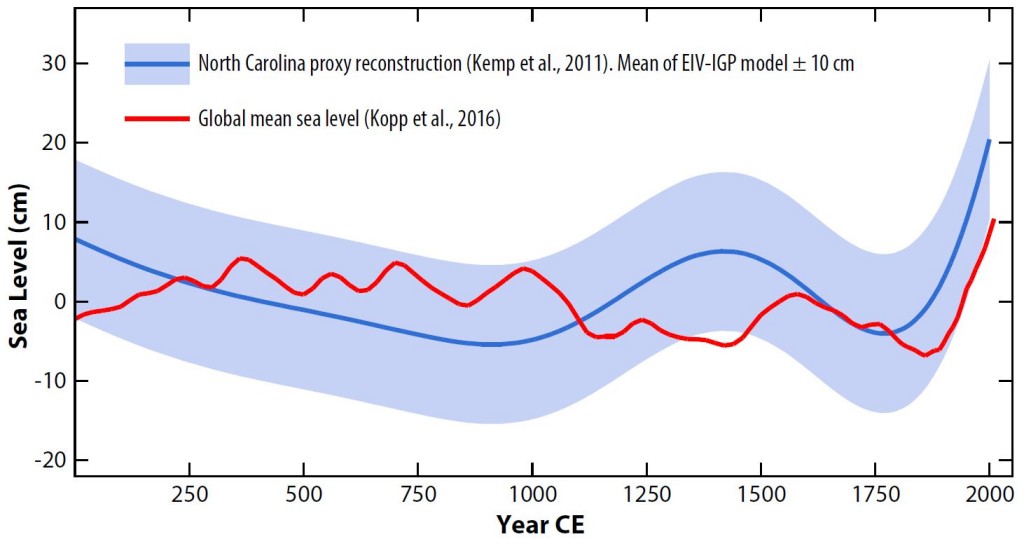

One question I was asked by a journalist was how the new results compare with our previous study (Kemp et al. 2011), which reconstructed the last two millennia of sea level in North Carolina based on cores from the Outer Banks. Sea level changes in one place can of course differ substantially from the global sea level history. In that paper we therefore estimated the expected size of these deviations on the basis of known physical processes, and came to the conclusion:

This analysis suggests that our data can be expected to track global mean sea level within about ±10 cm over the past two millennia.

The graph below shows a direct comparison of the new global and the former regional curves. (To allow a fair comparison, the uncertainty about a linear background rate discussed above was treated in the same manner in both curves, namely by removing the linear trend over the pre-industrial period AD 0-1800.)

Fig. 4 Comparison of the new global curve of Kopp et al. (2016) with the regional curve for North Carolina by Kemp et al. (2011).

As we see, our assessment wasn’t bad at all.

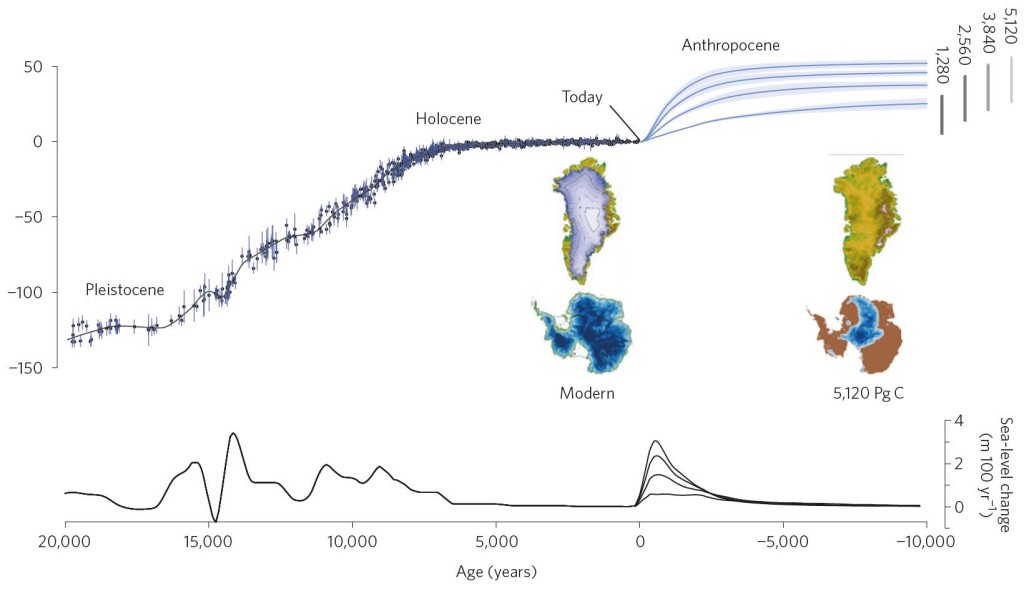

Ten thousand years of future sea level rise

Another recent paper, by 22 renowned researchers in Nature Climate Change (Clark et al. 2016), discusses the long-term sea level rise which we will cause by our emissions of the coming decades. Largely because of the slow response of the large ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica to global warming, the sea will continue to rise for at least ten thousand years even after global warming was stopped – longer than the history of human civilization. The reason is that the lifetime of CO2 in the atmosphere is very long – even millennia after we will have stopped burning fossil fuels, the CO2 content of the atmosphere and the global temperature will continue to be higher than now, and ice will continue to melt. Even if we limit global warming to 2°C, the likely end result will be a sea-level rise of around 25 meters.

Fig. 5 From the Ice Age to the Anthropocene: the last 20,000 and the next 10,000 years of sea level, by Clark et al. 2016. The vertical scale is measured here not in cm but in meters: at the height of the last Ice Age, at the start of the curve, global sea level was about 125 meters lower than today. Due to our greenhouse gas emissions we are currently setting in motion a sea-level rise of 25 to 50 meters above present levels. The small inset maps show the ice cover on Greenland and Antarctica. The lower curves give the rate of sea-level rise in meters per century.

This expected large sea-level rise does of course not surprise us paleoclimatologists, given that in earlier warm periods of Earth’s history sea level has been many meters higher than now due to the diminished continental ice cover (see the recent review by Dutton et al. 2015 in Science).

I have often emphasized the inexorable long-term effects of sea level rise in my lectures and articles over the years. Often I was told that people don’t care about what will happen in thousands of years – they are at best interested in the lifetime of their children and grandchildren. Would you agree with that? I would hope that we do care how future generations will see the legacy that we leave them.

Links

New York Times: Seas Are Rising at Fastest Rate in Last 28 Centuries

Washington Post: Seas are now rising faster than they have in 2,800 years, scientists say

Associated Press: Seas are rising way faster than any time in past 2,800 years

Scientific American: New Data Reveal Stunning Acceleration of Sea Level Rise

Phys.org: Sea level rise in 20th century was fastest in 3,000 years, study finds

Phys.org: Sea-level rise past and future: Robust estimates for coastal planners

The Independent: Sea levels ‘could rise by more than a metre’ if global warming is not tackled, says new study

USA Today: Sea levels rising faster now than in past 3,000 years

References

- R.E. Kopp, A.C. Kemp, K. Bittermann, B.P. Horton, J.P. Donnelly, W.R. Gehrels, C.C. Hay, J.X. Mitrovica, E.D. Morrow, and S. Rahmstorf, "Temperature-driven global sea-level variability in the Common Era", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517056113

- R. Rietbroek, S. Brunnabend, J. Kusche, J. Schröter, and C. Dahle, "Revisiting the contemporary sea-level budget on global and regional scales", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, pp. 1504-1509, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1519132113

- S. Rahmstorf, "A Semi-Empirical Approach to Projecting Future Sea-Level Rise", Science, vol. 315, pp. 368-370, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1135456

- M. Mengel, A. Levermann, K. Frieler, A. Robinson, B. Marzeion, and R. Winkelmann, "Future sea level rise constrained by observations and long-term commitment", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, pp. 2597-2602, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1500515113

- B.P. Horton, S. Rahmstorf, S.E. Engelhart, and A.C. Kemp, "Expert assessment of sea-level rise by AD 2100 and AD 2300", Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 84, pp. 1-6, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.11.002

- E. Gasson, R.M. DeConto, D. Pollard, and R.H. Levy, "Dynamic Antarctic ice sheet during the early to mid-Miocene", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, pp. 3459-3464, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516130113

- R. Levy, D. Harwood, F. Florindo, F. Sangiorgi, R. Tripati, H. von Eynatten, E. Gasson, G. Kuhn, A. Tripati, R. DeConto, C. Fielding, B. Field, N. Golledge, R. McKay, T. Naish, M. Olney, D. Pollard, S. Schouten, F. Talarico, S. Warny, V. Willmott, G. Acton, K. Panter, T. Paulsen, M. Taviani, . , G. Acton, R. Askin, C. Atkins, K. Bassett, A. Beu, B. Blackstone, G. Browne, A. Ceregato, R. Cody, G. Cornamusini, S. Corrado, R. DeConto, P. Del Carlo, G. Di Vincenzo, G. Dunbar, C. Falk, B. Field, C. Fielding, F. Florindo, T. Frank, G. Giorgetti, T. Grelle, Z. Gui, D. Handwerger, M. Hannah, D.M. Harwood, D. Hauptvogel, T. Hayden, S. Henrys, S. Hoffmann, F. Iacoviello, S. Ishman, R. Jarrard, K. Johnson, L. Jovane, S. Judge, M. Kominz, M. Konfirst, L. Krissek, G. Kuhn, L. Lacy, R. Levy, P. Maffioli, D. Magens, M.C. Marcano, C. Millan, B. Mohr, P. Montone, S. Mukasa, T. Naish, F. Niessen, C. Ohneiser, M. Olney, K. Panter, S. Passchier, M. Patterson, T. Paulsen, S. Pekar, S. Pierdominici, D. Pollard, I. Raine, J. Reed, L. Reichelt, C. Riesselman, S. Rocchi, L. Sagnotti, S. Sandroni, F. Sangiorgi, D. Schmitt, M. Speece, B. Storey, E. Strada, F. Talarico, M. Taviani, E. Tuzzi, K. Verosub, H. von Eynatten, S. Warny, G. Wilson, T. Wilson, T. Wonik, and M. Zattin, "Antarctic ice sheet sensitivity to atmospheric CO 2 variations in the early to mid-Miocene", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, pp. 3453-3458, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516030113

- A.C. Kemp, B.P. Horton, J.P. Donnelly, M.E. Mann, M. Vermeer, and S. Rahmstorf, "Climate related sea-level variations over the past two millennia", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 108, pp. 11017-11022, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1015619108

- P.U. Clark, J.D. Shakun, S.A. Marcott, A.C. Mix, M. Eby, S. Kulp, A. Levermann, G.A. Milne, P.L. Pfister, B.D. Santer, D.P. Schrag, S. Solomon, T.F. Stocker, B.H. Strauss, A.J. Weaver, R. Winkelmann, D. Archer, E. Bard, A. Goldner, K. Lambeck, R.T. Pierrehumbert, and G. Plattner, "Consequences of twenty-first-century policy for multi-millennial climate and sea-level change", Nature Climate Change, vol. 6, pp. 360-369, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2923

- A. Dutton, A.E. Carlson, A.J. Long, G.A. Milne, P.U. Clark, R. DeConto, B.P. Horton, S. Rahmstorf, and M.E. Raymo, "Sea-level rise due to polar ice-sheet mass loss during past warm periods", Science, vol. 349, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa4019

#48 “We don’t know when Thwaites will cross its tipping point”

Regardless of AGW mitigation? Nothing we can do about it? Or is it too late?

He sounds elated, which seems strange.

for Victor, who posted the same comment at the Alley talk:

— listen to the intro again. Note the description up to around

“The key thing about a talk by Richard Alley …”

You should feel smarter. If that didn’t work, try listening to him again.

And, Victor, did you listen to the words?

If you hear someone talking to you in the tone Alley uses, and you’ve parked your car on a railroad track to take a nap — see if you can figure out what the tone conveys in time to do something appropriate.

I think Thwaites (and neighbors) have come unstuck already.

doi: 10.1002/2014GL060140

Now we just argue about the rate of collapse.

Victor, you have to listen through the whole video.

When you get to around 34:00 — if you’ve gotten smarter listening to and watching the lead-up to that — then you don’t need to ask the questions you’re asking here, because they’ve been answered.

I know, why am I bothering? Just bored, I guess.

29 – if an atmosphere warmed and sea level fell, then an explanation might be the heat came out of the oceans… causing a drop in the steric component of the GMSL. Then atmospheric CO2 could fall due to cooler oceans, and a little fella ice age might ensue.

What’s the basis for the statement regarding aCO2 residence time being “millennia after we will have stopped burning fossil fuels” ?

Presuming that residence time is true then on that time scale shouldn’t we also be concerned that the Holocene inter-glacial will be coming to a natural end? Anthropogenic CO2 and millienia-long residence time might then be the savior of civilization’s future rather than its demise.

“Often I was told that people don’t care about what will happen in thousands of years – they are at best interested in the lifetime of their children and grandchildren. Would you agree with that? I would hope that we do care how future generations will see the legacy that we leave them.”

Do you spend much time castigating our remote ancestors for inventing religion, democracy, and capitalism which in turn led to western civilization, industrialization, and fossil fuel consumption?

FYI – I posted the two questions that you just dismissed here in moderation on Judy Curry’s blog simultaneous with here and also predicting they’d be dismissed. Thanks for living up to my low expectations. Now more people know you refuse to answer difficult questions.

P.S.: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L2m9SNzxJJA

> I was a bit dismayed that Hansen didn’t mention

“You can’t have everything. Where would you put it?”

Those of us kibitzing and trying to learn the science as amateurs often miss the fact that the real scientists mostly all know most all of this stuff and take it as known when discussing particular papers. Notice the number of subsequent papers citing any given paper — or not — as a reminder how much of this is figuring into what’s being said.

Listen to some of Alley’s talks video’d on YouTube (e.g. one mentioned above). Every few sentences and every few slides he mentions an idea or an image he’s borrowed from another scientist’s work (and often enough says they’re in the audience and could explain it better). He puts it all together.

That’s why his lectures are like going to a Disney park (or a nightmare version of one, as when he asks if he’s wasted his life working out the facts the politicians have ignored). They’re full of excitement in all sorts of ways.

He also makes the point clearly in one of those videos we’d do well to remember — that of the ones he’s met, most politicians behind closed doors away from the media are mostly awesomely smart and interested and informed about the science. But — a big one — once the doors open and the media comes in they’re suddenly speaking only in scripted phrases, because they can be destroyed by one single mistaken comment out of a thousand correct ones.

Actually i was thinking more of

doi:10.1126/science.1249055

If RealClimate would publish graphs with the notice of CC-BY-SA 3.0 or 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) those graphs could be used more easily elsewhere. This commons license requires the mention of the author, thus another way to potentially help expose more minds to the issue.

The take home message is that we are likely seeing considerable SLR withing decades, which is of great concern for home owners and insurers.

It would be enough to place a license notice on a sub page, like about, so you can retroactive declare copyrights, and add unless otherwise noted.

#57–“What’s the basis for the statement regarding aCO2 residence time being “millennia after we will have stopped burning fossil fuels” ?”

You could try my summary of David Archer’s “Long Thaw”, here:

http://hubpages.com/education/The-Long-Thaw-A-Review

DS 59,

I hope you don’t sprain your arm patting yourself on the back. Sometimes you won’t always get an answer the very same day. It rarely proves that you’ve posted a question “too difficult to answer.”

Yes, CO2 increase has saved us from the next ice age, which was due in 20,000 years. On the other hand, it threatens to take down our civilization due to agricultural failure in considerably less than 200 years. Which do you think we should be more concerned about?

David Springer @57,

The CO2 we add to the atmosphere is quickly reduced in quantity by absorption into oceans & biosphere. The apparent fraction of our emissions that remains (about 43%) is but the result of the continued and increasing level of our emissions. When we stop emitting, the level of CO2 resulting from our emissions will continue to fall but with diminishing effect. By 1,000 years following our emissions, the mechanisms that had been continuing to absorb our (now ceased) emissions will have reached an equilibrium leaving 20% to 30% of our emissions still sloshing around the atmosphere. (The more we emit, the higher the remaining level.) At that point, CO2 requires a geological sink and that will take millennia. That is, to use the words of one of our hosts,“The remaining CO2 is abundant enough to continue to have a substantial impact on climate for thousands of years.”

The NH cooling that was in process prior to our emissions would have led to a cooler climate but one in which the orbital forcings were far weaker than those of recent ice age cycles. Any chance of a renewed ice age is already long gone.

David Springer @59.

FYI – I don’t understand what you’re talking about.

> Sidd … doi

Yep. That’s been cited, um, a lot:

Marine Ice Sheet Collapse Potentially Under Way

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/344/6185/735

by I Joughin – 2014 – Cited by 174

Warning: Events in Future are Closer Than They Appear

David Springer,

Thanks for confirming that you have no idea how to even assess whether a question is difficult. We now know that you are an imbecile whose posts can safely be ignored without losing any value.

> David Springer says …

You link your name to JC’s blog; why bother asking questions long since answered?

PS, reminding myself there are always new readers apt to come along — David Springer’s asking stuff long since answered that you should learn how to find for yourself — it will bring you up to date quickly to use the search tools.

E.g. for the questions he “predicted” would not be answered — they have been: https://www.google.com/search?q=site%3Arealclimate.org+interglacial+end

If David Springer’s only use for RealClimate is as a place to earn his science denial merit badge to show off at Judy’s place then it is indeed quite safe to ignore him.

Hank, True, but anyone who posts moronic questions, waits less than 2 hours for an answer and then trumpets their victory back at Aunt Judy’s place–they can safely be dismissed as morons.

M. A. Rodger: “David Springer @59.

FYI – I don’t understand what you’re talking about.”

You have that in common. He doesn’t understand what he’s talking about either.

I always thought the little ice age was from about 1600 to 1900, and the wikipedia article seems to reflect this, and includes a chart of Co2 from the Law Dome suggesting a global impact. However this study suggests sea level rose around just before, and although it fell throughout the rest of the period it didn’t really get any lower than it was around 1400.

Is this due to lags is SLR? The medieval warm period caused the relatively rapid (ignoring the last century) rise up to 1600, and the little ice age then caused a steady decline again from 1600 to near 1900?

#60 Thanks for that link, Hank. In his youtube lecture, Alley is so hyper he comes across almost like a crackpot, and to me he is not convincing. He seems to be taking pleasure in the dire predictions he’s tossing out, which suggests he’s enjoying all the attention more than he’s alarmed by the future. Crackpots typically invoke all sorts of “evidence” to support their theories, so all the evidence he musters isn’t really much help. I was especially disappointed in his dismissal of the question regarding volcanic activity the west Antarctic, which deserved a more thoughtful response \than the simplistic explanation he offered. When we find an underlying volcano in the precise area where a huge glacier is being undermined, that hardly seems like a coincidence — especially since the rest of the Antarctic presents a very different picture.

In the congressional hearing you linked us to, Alley comes across very differently. Maybe someone took him aside and gave him some advice on how to present himself in public. In any case, this time I was impressed.

How are you coming along Victor? I admire you for sticking with it here at RC. Keep an open mind. Speaking of which….

Tamino just posted this Al Gore TED Talk and Al has a lot of positive news. I’m wondering if we’ve turned a corner on the political front?

Any opinions or is the optimism unwarranted? At least we’re making progress on renewables it seems. I don’t know if the transitions will happen fast enough to save most of us. I would appreciate any sober assessments. Thanks

Victor, like most of the public, apparently gets most of his cues about what a speaker is saying from a speaker’s ‘pathos’ rather than ‘logos,’ (roughly style versus content), and a mismatch between the two causes a breakdown in his ability to hear the message.

This can be a problem, generally, for scientists trying to communicate with the broader public. (Though it should be pointed out here that Alley is speaking to an academic audience, who generally are better at listening first to content, and can distinguish excitement over scientific discovery over distress over dire consequences of the same.)

But I hope most of the public is not quite as full of themselves as our resident ‘winner’ to assume that they can judge the legitimacy of one of the world’s top glaciologists based on their vague impression of his tone of voice.

> Victor … In his youtube lecture, Alley …

Context. The first link wasn’t a “lecture” — it wasn’t prepared for YouTube for the general public.

That was Alley speaking very informally in a meeting among scientists that someone video’d. He keeps referring to the work done by others in the room, as you noticed earlier.

The one with Rohrbacher? I’d call it vast patience under creepiness.

You, too, may perhaps be somewhat less formal among friends than when facing Congressmen who are trying — very, very hard in that case — to spin the facts to suit their supporters

Never mind Victor. We should start calling you Vapid Victor. Your armchair psycho analysis of Richard Alley, trying to second guess his emotional state renders you the reining Crackpot. “Invoking evidence to support theories” is something smart people do. That totally leaves you out.

Now please go away.

#76 Thanks for the kind words, Chuck. And yes I’m keeping an open mind. On the topic of renewables I’m definitely with you. The future of humanity may not be with Mars, as the director of NASA has claimed, but it definitely has to be with renewables, because we will eventually run out of those fossil fuels so many are now so worked up over. And when we do, while THAT will be a disaster in the making for sure. So yes, research and development of renewables is essential, regardless of what side the climate change fence one is on. We’ll most likely run out of oil and gas long before the collapse of Thwaites, and when that happens, we’d better be prepared with alternatives.

#76–Chuck, that’s a question much on my mind, too. I don’t think there’s a clear answer yet. Over the long term, more fundamental questions than the nature of our electric generation mix need to be addressed–I think.

Even the short-term questions about RE deployment is still open: current deployment rates aren’t yet high enough to achieve our mitigation goals. On the other hand, they are far, far higher than anyone dared hope 10 years back, and if growth keeps to an exponential trajectory much longer, then they will be.

Victor, you have claimed you’re an academic.

” … we will eventually run out of those fossil fuels so many are now so worked up over. And when we do, while THAT will be a disaster …”

Indeed, the devil cites scripture. If we burn it all we might get to 1000ppm CO2.

I mistakenly assumed that the longer you hang around RC the more you become educated about Climate Change. I was hoping our friend had made some real progress. I spoke too soon.

We’re not going to burn our way through our FF supply and suddenly be in trouble from a lack of fossil fuel Victor. We’re in trouble now and the question is can we make a clean transition to renewable energy before it’s too late.

“The take home message is that we are likely seeing considerable SLR withing decades, which is of great concern for home owners and insurers.”

Comment by Chris Machens — 28 Feb 2016

From what i was able to tell, Thwaits is gonna collapse in a matter of decades raising sea levels by as much as 4 meters. Is that correct? Do i have this right or do I need to go back and listen again? I assume Dr. Alley is referring to the next few decades…… correct? Somebody help me out with this. What specific decades are we talking about here? Does this include the decade we’re in now?

Thanks in advance.

Chuck, Dr. Alley did not say Thwaits is gonna collapse in a matter of decades, he said once it recedes from it’s current grounding line and starts to head back down the retrograde slope it rests on at some point it could collapse within a matter of decades rather than centuries due to the growing height of its calving face and its shear weight. It’s all about ice strength and instability. Once (relatively) warm water gets underneath it will be over and rapid collapse will progress all the way across the basin to the Transantarctic mountains.

Contrary to Victor’s impression, Alley was actually pulling back from what he has said in previous talks that I’ve seen where he said it is pretty much already past the tipping point where full collapse is inevitable. In this talk he says we may not be there yet.

The latter.

Prediction is hard, especially about the future.

for Chuck Hughes, ‘oogle Richard Alley sea level antarctica

and limit to “verbatim” and look for recent results, e.g. this one:

http://arstechnica.com/science/2015/07/no-scientists-arent-predicting-10ft-higher-sea-level-by-2050/

And much else. He’s talking about what we don’t know, he’s not predicting a sure thing in a certain time span.

doi: 10.1002/2016GL067758

Research Letter

Episodic ice velocity fluctuations triggered by a subglacial flood in West Antarctica

The implication of non-radiative energy fluxes dominating Greenland ice sheet exceptional ablation area surface melt in 2012

DOI: 10.1002/2016GL067720

Thanks for the Fausto article on nonradiative heat flux into GIS. I like the quantification of how moist air melts ice.

It’s important to realize how rapidly our environment is changing due to global warming. These graphs (even though possibly slightly inaccurate) definitely show the concerning change in our oceans’ sea level. This could mean a huge change for us and future generations. We, as a people, country, and world, should consider this our problem and find a way to stop or slow down this before it’s too late.

@Stefan’s response to #17: Till today tourists prefer old Male over new Hulhumale: https://www.tripadvisor.in/Tourism-g293953-Maldives-Vacations.html

I like how you used many graphs to help visualize how drastic climate change really is. How much impact do you think a 24-131 cm increase in sea level will affect the US and what do you think we should do to prepare for it?

#92–“Till today tourists prefer old Male over new Hulhumale…”

Yes, they want to see it while they still can.

Stefan

In your Figure 1, what is the averaging time for the historical data, and how do you account for the smoothing when you splice the modern record (post 2000) onto it.

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/11/just-nudge-could-collapse-west-antarctic-ice-sheet-raise-sea-levels-3-meters

If you only read the abstract, it sounds like West Antarctica is going to loose its ice over the next few decades. You have to read the whole thing to see where it says several thousand years. I think I remember derivative publications saying “over the next few decades.”

http://www.antarcticglaciers.org/2014/05/west-antarctic-ice-sheet-collapsing/

talks about the reverse slope after the grounding line. It is easy to not read the whole thing.

Stefan: Based on many sources, sea level has risen at a much faster rate in the 20th century than it could have on the average over the past few millennia. However, before accepting these global SLR reconstruction (all based on coastal cores?), I would like to see reference(s) showing that drill core sediments can accurately reconstruct LOCAL SLR as measured by tide gauges. For local records, no GIA adjustment is needed. Figure 2 in this post shows a slight fall in sea level in the 19th century – a very surprising result given the end of the LIA and the 5 cm of SLR in the late 19th century shown by composites of tide gauge records. For example, see http://www.cmar.csiro.au/sealevel/.

I looked at Kemp (2011) http://www.pnas.org/content/108/27/11017.short and was unimpressed by the relatively short period of overlap between tidal records and “SL proxy records”, all from a relatively short period when SL was rising. Kemp (2009) discusses many caveats of using foraminifer in salt marshes as proxy for SL, mainly that they are a proxy for salinity rather than SL and that salt marshes like those behind the Outer Banks are highly changeable environments. Are there sites with tide gauge and proxy data going back to the early 1800’s when SL wasn’t rising or sites where GIA has negated SLR?

Thanks, Hank Roberts for the pointer at #89 on Google “search tools” filters. I spend much more time doing custom queries at scholar.google.com where different options that those are offered; I never noticed this on the main google.com search page. I had known about the + operator and didn’t notice this was replaced. Oddly, it appears all this changed back in 2011!?

http://searchengineland.com/responding-to-complaints-google-adds-verbatim-search-results-101226

Feynman: Hell, if I could explain it to the average person, it wouldn’t have been worth the Nobel prize.