Guest post by Brigitte Knopf

Global emissions continue to rise further and this is in the first place due to economic growth and to a lesser extent to population growth. To achieve climate protection, fossil power generation without CCS has to be phased out almost entirely by the end of the century. The mitigation of climate change constitutes a major technological and institutional challenge. But: It does not cost the world to save the planet.

This is how the new report was summarized by Ottmar Edenhofer, Co-Chair of Working Group III of the IPCC, whose report was adopted on 12 April 2014 in Berlin after intense debates with governments. The report consists of 16 chapters with more than 2000 pages. It was written by 235 authors from 58 countries and reviewed externally by 900 experts. Most prominent in public is the 33-page Summary for Policymakers (SPM) that was approved by all 193 countries. At a first glance, the above summary does not sound spectacular but more like a truism that we’ve often heard over the years. But this report indeed has something new to offer.

The 2-degree limit

For the first time, a detailed analysis was performed of how the 2-degree limit can be kept, based on over 1200 future projections (scenarios) by a variety of different energy-economy computer models. The analysis is not just about the 2-degree guardrail in the strict sense but evaluates the entire space between 1.5 degrees Celsius, a limit demanded by small island states, and a 4-degree world. The scenarios show a variety of pathways, characterized by different costs, risks and co-benefits. The result is a table with about 60 entries that translates the requirements for limiting global warming to below 2-degrees into concrete numbers for cumulative emissions and emission reductions required by 2050 and 2100. This is accompanied by a detailed table showing the costs for these future pathways.

The IPCC represents the costs as consumption losses as compared to a hypothetical ‘business-as-usual’ case. The table does not only show the median of all scenarios, but also the spread among the models. It turns out that the costs appear to be moderate in the medium-term until 2030 and 2050, but in the long-term towards 2100, a large spread occurs and also high costs of up to 11% consumption losses in 2100 could be faced under specific circumstances. However, translated into reduction of growth rate, these numbers are actually quite low. Ambitious climate protection would cost only 0.06 percentage points of growth each year. This means that instead of a growth rate of about 2% per year, we would see a growth rate of 1.94% per year. Thus economic growth would merely continue at a slightly slower pace. However, and this is also said in the report, the distributional effects of climate policy between different countries can be very large. There will be countries that would have to bear much higher costs because they cannot use or sell any more of their coal and oil resources or have only limited potential to switch to renewable energy.

The technological challenge

Furthermore – and this is new and important compared to the last report of 2007 – the costs are not only shown for the case when all technologies are available, but also how the costs increase if, for example, we would dispense with nuclear power worldwide or if solar and wind energy remain more expensive than expected.

The results show that economically and technically it would still be possible to remain below the level of 2-degrees temperature increase, but it will require rapid and global action and some technologies would be key:

Many models could not achieve atmospheric concentration levels of about 450 ppm CO2eq by 2100, if additional mitigation is considerably delayed or under limited availability of key technologies, such as bioenergy, CCS, and their combination (BECCS).

Probably not everyone likes to hear that CCS is a very important technology for keeping to the 2-degree limit and the report itself cautions that CCS and BECCS are not yet available at a large scale and also involve some risks. But it is important to emphasize that the technological challenges are similar for less ambitious temperature limits.

The institutional challenge

Of course, climate change is not just a technological issue but is described in the report as a major institutional challenge:

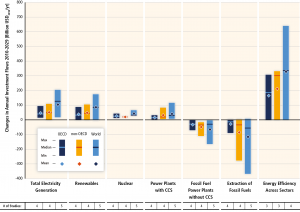

Substantial reductions in emissions would require large changes in investment patterns

Over the next two decades, these investment patterns would have to change towards low-carbon technologies and higher energy efficiency improvements (see Figure 1). In addition, there is a need for dedicated policies to reduce emissions, such as the establishment of emissions trading systems, as already existent in Europe and in a handful of other countries.

Since AR4, there has been an increased focus on policies designed to integrate multiple objectives, increase co‐benefits and reduce adverse side‐effects.

The growing number of national and sub-national policies, such as at the level of cities, means that in 2012, 67% of global GHG emissions were subject to national legislation or strategies compared to only 45% in 2007. Nevertheless, and that is clearly stated in the SPM, there is no trend reversal of emissions within sight – instead a global increase of emissions is observed.

Figure 1: Change in annual investment flows from the average baseline level over the next two decades (2010 to 2029) for mitigation scenarios that stabilize concentrations within the range of approximately 430–530 ppm CO2eq by 2100. Source: SPM, Figure SPM.9

Trends in emissions

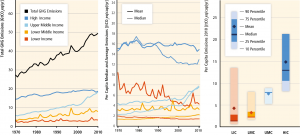

A particularly interesting analysis, showing from which countries these emissions originate, was removed from the SPM due to the intervention of some governments, as it shows a regional breakdown of emissions that was not in the interest of every country (see media coverage here or here). These figures are still available in the underlying chapters and the Technical Summary (TS), as the government representatives may not intervene here and science can speak freely and unvarnished. One of these figures shows very clearly that in the last 10 years emissions in countries of upper middle income – including, for example, China and Brazil – have increased while emissions in high-income countries – including Germany – stagnate, see Figure 2. As income is the main driver of emissions in addition to the population growth, the regional emissions growth can only be understood by taking into account the development of the income of countries.

Historically, before 1970, emissions have mainly been emitted by industrialized countries. But with the regional shift of economic growth now emissions have shifted to countries with upper middle income, see Figure 2, while the industrialized countries have stabilized at a high level. The condensed message of Figure 2 does not look promising: all countries seem to follow the path of the industrialized countries, with no “leap-frogging” of fossil-based development directly to a world of renewables and energy efficiency being observed so far.

Figure 2: Trends in GHG emissions by country income groups. Left panel: Total annual anthropogenic GHG emissions from 1970 to 2010 (GtCO2eq/yr). Middle panel: Trends in annual per capita mean and median GHG emissions from 1970 to 2010 (tCO2eq/cap/yr). Right panel: Distribution of annual per capita GHG emissions in 2010 of countries within each income group (tCO2/cap/yr). Source: TS, Figure TS.4

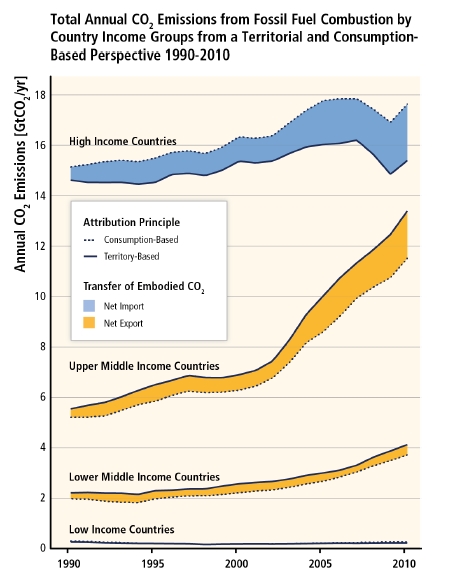

But the fact that today’s emissions especially rise in countries like China is only one side of the coin. Part of the growth in CO2 emissions in the low and middle income countries is due to the production of consumption goods that are intended for export to the high-income countries (see Figure 3). Put in plain language: part of the growth of Chinese emissions is due to the fact that the smartphones used in Europe or the US are produced in China.

Figure 3: Total annual CO2 emissions (GtCO2/yr) from fossil fuel combustion for country income groups attributed on the basis of territory (solid line) and final consumption (dotted line). The shaded areas are the net CO2 trade balance (difference) between each of the four country income groups and the rest of the world. Source: TS, Figure TS.5

The philosophy of climate change

Besides all the technological details there has been a further innovation in this report, that is the chapter on “Social, economic and ethical concepts and methods“. This chapter could be called the philosophy of climate change. It emphasizes that

Issues of equity, justice, and fairness arise with respect to mitigation and adaptation. […] Many areas of climate policy‐making involve value judgements and ethical considerations.

This implies that many of these issues cannot be answered solely by science, such as the question of a temperature level that avoids dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system or which technologies are being perceived as risky. It means that science can provide information about costs, risks and co-benefits of climate change but in the end it remains a social learning process and debate to find the pathway society wants to take.

Conclusion

The report contains many more details about renewable energies, sectoral strategies such as in the electricity and transport sector, and co-benefits of avoided climate change, such as improvements of air quality. The aim of Working Group III of the IPCC was, and the Co-Chair emphasized this several times, that scientists are mapmakers that will help policymakers to navigate through this difficult terrain in this highly political issue of climate change. And this without being policy prescriptive about which pathway should be taken or which is the “correct” one. This requirement has been fulfilled and the map is now available. It remains to be seen where the policymakers are heading in the future.

The report :

Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change – IPCC Working Group III Contribution to AR5

Brigitte Knopf is head of the research group Energy Strategies Europe and Germany at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and one of the authors of the report of the IPCC Working Group III and is on Twitter as @BrigitteKnopf

Reaclimate coverage of the IPCC 5th Assessment Report:

Summary of Part 1, Physical Science Basis

Summary of Part 2, Impacts, Adaptation, Vulnerability

Thank you. Very good and useful summary.

It’s not exactly that the monetary costs will be ‘quite low’ (0.06% Growth per year, etc.), and I think this point was made, but it’s that beneath that aggregate is a substantial– HUGE transfer of investment and wealth across all sorts of entrenched business sectors and interests, with lots of nested localized economies beneath the “country” level whose very survival is on the line (can a deep valley coal-mining town become an efficient solar hub?) As with what you said, these policy decisions necessarily transcend climate realities.

When reading this report, I can’t help but think only the most shrill communist/monarchical government structures can pull off these kinds of feats. In America, the local representative system might make it impossible since it takes as few as five states to kill any program idea if its elected representatives find it a loser for them at home.

And speaking of ‘home’, it needs to be said again– another huge killer of policy possibilities are environmentalists themselves who deny the reality that their backyard must also be a candidate for the large-scale deployment of energy installations in order to pull off what is said to be necessary — even more-so without Nuclear or Fracking, etc. Every wind-energy and biomass installation projects I’ve been around has faced opposition, and the most successful of the opposers have been, without fail, an environmentalist. They are the ones armed with the knowledge, can manipulate the liabilities, and are a master of appeals for further impact study/review.

Given that it now can take up to 10 years to get a new large-scale energy plant installed and online, hitting those 2029 targets are going to require those who want to stand up for reducing/eliminating fossile fuels to also stand up to having lagre scale installations beyond-solar within their own eye-sight.

Most interesting. Thanks to Dr. Knopf!

From a process standpoint, this part needs to be far better known, IMO:

The headline item, of course, is the good news that:

“Ambitious climate protection would cost only 0.06 percentage points of growth each year. This means that instead of a growth rate of about 2% per year, we would see a growth rate of 1.94% per year.”

(A statement that surely will not pass without controversy here.)

But this can hardly be called good news:

That bit is essentially a guarantee that the political terrain isn’t going to get any easier.

http://bravenewclimate.com/2014/04/14/ipcc-double-standards-on-energy-barriers/

Maybe someone can clarify something for me. The article points out that the consumption losses are based on a hypothetical ‘business-as-usual’ case. However – as I understand it – this does not include the possible impacts of climate change itself (i.e., the hypothetical BAU appears to be one in which GDP continues to grow at roughly the current rate). Firstly, am I right about this? Secondly is there an easy way to compare the consumption losses due to mitigation with consumption losses if we choose not to mitigate and follow some particular emission scenario. I have found a section in WGII that discusses the annual costs of climate change (0.2 – 2% per year) but this doesn’t immediately tell me – I think – what impact this has on GDP growth (which is what I think is needed to do a proper comparison).

@5

The BAU paths do essentially assume continued economic growth at roughly the current rates, although it is more complex than just making that assumption.

As for the Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) on which these projections are based, there are two differing philosophies. The first include both costs of mitigation and costs of damages and then perform a cost-benefit analysis. Models like DICE/RICE and FUND are examples of this approach. These are also the models used to arrive at the EPA social cost of carbon values.

The second philosophy is that of a cost-effectiveness analysis, in which, for example, a physically-based mitigation target is chosen (2 degrees C, 450 ppm, etc.) and then the economically effective pathway toward that goal is found. In this approach, there is no damage function or cost of climate change damages included in the calculation.

Fundamentally, there are many questions to be asked about the economic/energy system/climate coupled models that are used. The fact that many different models with varying input assumptions, technological detail and model solution techniques all come up with very low costs for mitigation is interesting. These can be interpreted, at least from the point of view discussed here, as conservative estimates of cost, exactly because the potential costs of damages in the face of inaction are not even included.

Mitigation of Climate Change – Part 3 of the new IPCC report:

“This implies that many of these issues cannot be answered solely by science, such as the question of a temperature level that avoids dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system or which technologies are being perceived as risky. It means that science can provide information about costs, risks and co-benefits of climate change but in the end it remains a social learning process and debate to find the pathway society wants to take.”

Ah, the perfect cop-out. Science, and let’s be specific, climate scientists, cannot answer ‘the question of a temperature level that avoids dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system’….. Of course not; if they did honestly and forthrightly, does anyone believe countries like Australia, Canada, Russia, USA, Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia, et al, would have signed off on that. This way, they can talk about continued growth, with perhaps a minimal reduction to pay homage to the need for ameliorating climate change, and everyone’s happy. Now we see the real value of the fictitious 2 C target. Nothing to do with avoiding the climate Apocalypse; everything to do with selling economic prosperity forever.

In terms of growth, it appears that the US is in a good position. By cutting our per capita emissions down below 3 tonne carbon dioxide per year we can expect 2.4% annual growth. http://www.rmi.org/reinventingfire That is substantially higher than the expected world economic growth, with or without mitigation. There is a good opportunity here to partner with low income and low middle income nations that are already at that target level (Figure 2.) to help them retain their low per capita emissions status while sharing in our expected healthy economic growth. Our strong environmental laws give us standing with the WTO to impose tariffs on imports from the upper middle income countries with rising per capita emissions that don’t have strong environmental protection laws. The suggested partnership could be funded, in part, by the revenue stream made available by those tariffs. Legislative efforts in the partner countries putting in place strong environmental protections may allow them to impose tariffs on their own as well with out possibility of retribution from trading partners that lack such laws. That may give them a balance of trade that can assist with economic growth.

On suppression in the SPM, news reports also indicate that mention of mobilizing large amounts of money for the sort of effort I am describing were also removed. Based on Figure 2. that seems only practical. Failure of middle income countries to commit to emissions reductions means adaptation costs will be especially high for countries with large historic investments in infrastructure. (Those without such investments will face morbidity and mortality costs in higher proportion to financial losses.) Foregoing development goals would retain money to help cover those costs while at the same time leave a number of nations at a low per capita emissions level owing to lack of development. Their situation does not improve and likely deteriorates, but they don’t make things much worse for everyone else either (except for increased military intervention the Pentagon is anticipating and large refugee burdens on some Continents).

But perhaps the most important thing not mentioned in the SMP for understanding strange attitudes towards the present situation is that “Non-Annex I countries as a group have a share in the cumulative global greenhouse emissions for the period 1850 to 2010 close to 50%, a share that is increasing,” which is pointed out in Chapter 13 of the underlying report. Everything hinges on China.

“Put in plain language: part of the growth of Chinese emissions is due to the fact that the smartphones used in Europe or the US are produced in China,” which refuses to control emissions in a bid to claim market share after accession to the WTO. Europe and the US have absolutely no choice where there smartphones come from unless they invoke the environmental sections of the GATT. Failure to do so is the only thing that makes them the least bit complicit in China’s sovereign choices on emissions policy. Free trade should mean global prosperity, not global destruction, which is why GATT is written as it is. It is time for Europe and the US to show leadership by imposing carbon tariffs in Chinese imports.

to “And Then There’s Physics”:

A somehow lengthy answer, but the cost issue is complicated.

The important paragraph in the SPM of WGIII reads:

“Under these assumptions, mitigation scenarios that reach atmospheric concentrations of about 450ppm CO2eq by 2100 entail

losses in global consumption—not including benefits of reduced climate change as well as co-benefits and adverse side‐effects of mitigation19—of 1% to 4% (median: 1.7%) in 2030, 2% to 6%(median: 3.4%) in 2050, and 3% to 11% (median: 4.8%) in 2100 relative to consumption in baseline

scenarios that grows anywhere from 300% to more than 900% over the century. These numbers correspond to an annualized reduction of consumption growth by 0.04 to 0.14 (median: 0.06)percentage points over the century relative to annualized consumption growth in the baseline that is between 1.6% and 3% per year.” (SPM WGIII)

Footnote 19, where the paragraph is referring to, says:

“The total economic effects at different temperature levels would include mitigation costs, co‐benefits of mitigation, adverse side‐effects of mitigation, adaptation costs and climate damages. Mitigation cost and

climate damage estimates at any given temperature level cannot be compared to evaluate the costs and benefits of mitigation. Rather, the consideration of economic costs and benefits of mitigation should include

the reduction of climate damages relative to the case of unabated climate change.”(SPM WGIII)

So it mainly says that mitigation costs and climate damages cannot be compared. One problem is e.g. that estimates of damages include risks with low probability but high impacts (e.g. melting of Greenland ice-sheet) that can hardly measured while the risks of mitigation can much better be calculated.

On the cost estimates of damages, WGII SPM says:

“With these recognized limitations, the incomplete estimates of global annual economic losses for additional temperature increases of ~2°C are between 0.2 and 2.0% of income (±1 standard deviation around the mean) (medium evidence, medium agreement). Losses are more likely than not to be greater, rather than smaller, than this range (limited evidence, high agreement).” (SPM WGII)

Actually, it doesn’t say anything whether these are aggregated and discounted numbers over the whole century or whether these are numbers in a specific year and whether these are GDP or consumption losses, so it is even harder to compare to WGIII numbers, despite the methodological difficulties mentioned above and in the footnote.

Hope this helps a little bit and at least makes clear the methodological difficulties in comparing costs in WGII with costs in WGII

An answer to “And Then There’s Physics”

It is an somehow lengthy answer, but the cost issue is complicated.

The important paragraph in the SPM of WGIII reads:

“Under these assumptions, mitigation scenarios that reach atmospheric concentrations of about 450ppm CO2eq by 2100 entail losses in global consumption—not including benefits of reduced climate change as well as co-benefits and adverse side‐effects of mitigation19—of 1% to 4% (median: 1.7%) in 2030, 2% to 6% (median: 3.4%) in 2050, and 3% to 11% (median: 4.8%) in 2100 relative to consumption in baseline scenarios that grows anywhere from 300% to more than 900% over the century. These numbers correspond to an annualized reduction of consumption growth by 0.04 to 0.14 (median: 0.06) percentage points over the century relative to annualized consumption growth in the baseline that is between 1.6% and 3% per year.“ (SPM WGIII)

Footnote 19, where the paragraph is referring to, says:

“The total economic effects at different temperature levels would include mitigation costs, co‐benefits of mitigation, adverse side‐effects of mitigation, adaptation costs and climate damages. Mitigation cost and climate damage estimates at any given temperature level cannot be compared to evaluate the costs and benefits of mitigation. Rather, the consideration of economic costs and benefits of mitigation should include the reduction of climate damages relative to the case of unabated climate change.” (SPM WGIII)

So it mainly says that mitigation costs and climate damages cannot be compared. One problem is e.g. that estimates of damages include risks with low probability but high impacts (e.g. the extinction of some small island states) that can hardly measured while the risks of mitigation can much better be calculated.

On the cost estimates of damages, WGII SPM says:

“With these recognized limitations, the incomplete estimates of global annual economic losses for additional temperature increases of ~2°C are between 0.2 and 2.0% of income (±1 standard deviation around the mean) (medium evidence, medium agreement). Losses are more likely than not to be greater, rather than smaller, than this range (limited evidence, high agreement).” (SPM WGII)

Actually, it doesn’t say anything whether these are aggregated and discounted numbers over the whole century or whether these are numbers in a specific year, so it is even harder to compare to WGIII numbers, despite the methodological difficulties mentioned above and in the footnote.

Hope this helps a little bit to or at least makes it clear that there are huge methodological difficulties in comparing the costs between WGII and WGIII.

“Furthermore – and this is new and important compared to the last report of 2007 – the costs are not only shown for the case when all technologies are available, but also how the costs increase if, for example, we would dispense with nuclear power worldwide or if solar and wind energy remain more expensive than expected.”

I guess data shuts down in this report at around 2010. It has been mentioned at times, and borne out in 2011, that nuclear power disasters can increase emissions. Our current rate of major accidents is about one every twenty years, but most new nuclear builds are being done on the cheap, so we might expect that rate to increase owing to neglect of safety considerations. Further, in economies where nuclear safety is taken seriously, nuclear power in known to have a high opportunity cost with respect to other low carbon energy sources: http://www.rmi.org/Knowledge-Center/Library/E09-01_NuclearPowerClimateFixOrFolly leading to slowed mitigation efforts. And, in the US. existing nuclear power is being phased out owing, in part, to competition from wind energy, which presumably reduces the claimed phase out cost in Table SPM 2. Perhaps the report is not sufficiently up-to-date in this area to be a reliable guide on policy.

2 Davos says …And speaking of ‘home’, it needs to be said again– another huge killer of policy possibilities are environmentalists themselves… Every wind-energy and biomass installation projects I’ve been around has faced opposition, and the most successful of the opposers have been, without fail, an environmentalist…

A useful reminder that “environmentalist” does not equal sustainability-ist. (Yes, I make up words.)

hitting those 2029 targets are going to require those who want to stand up for reducing/eliminating fossile fuels to also stand up to having lagre scale installations beyond-solar within their own eye-sight.

Well, not exactly. Since large-scale utilities have characteristics opposite those found in sustainable systems(Privately owned, growth-dependent, massive, resource intensive, technology-dependent), uh, no.

Second, given consumption of resources is another spiral arm on this Perfect Storm, which the IPCC naturally ignores but we must address, and the resources don’t exist for current consumption, let alone growth in consumption, we may note that the economic considerations simply cannot be considered because this economy cannot continue, prima facia. We must reduce consumption to something along the lines of 10% of current, something for which the grid is not necessary. Thus, these environmentalists must get ready for local energy production. Given the pattern for sustainable communities is small, compact communities surrounded by land of various types of uses, and much more land essentially left “natural”, the scale and location of energy production will not continue to be major problem with environmentalists. Besides, most of them will be changing over to being practitioners of sustainability.

(Looking for, but cannot find, a recent article in which a climate scientist talks about massively reduced consumption.)

Following up on Physics at 5,

If sea level rose 4 feet and Miami (and the rest of east Florida) had to be abandoned, which is well within the upper range of sea level rise, the damage would be much more than 0.06% of US GDP. This applies to all sea coast countries. How does the cost of mitigation compare to the cost of moving to higher ground? What is the cost of current droughts, heat waves and extreme weather? Surely BAU has to include the losses from more extreme weather, drought and sea level rise.

32 years of 95% certainty is why it’s called; “BELIEF”

The debate is about why science has been only 95% certain that THE END IS NEAR instead of being 100% certain that the ultimate disaster of a climate crisis WILL happen. Scientists have doomed children as well so why do they perpetuate this costly debate? And do you see the millions of good and honest people in the global scientific community acting like THE END IS NEAR for them and billions of innocent children? NOTHING is worse than a climate crisis except a comet hit maybe but science is 100% sure they are “inevitable”. Science is 100% certain the planet is NOT flat and 95% certain Human CO2 COULD flatten it?

Don’t tell kids that science “believes” as much as you remaining “believers” do. Your eagerness to “believe” in this misery is sickening.

Just curious, when exactly are people with science backgrounds going to stop saying economic growth and sustainability in the same breath?! The only sustainable path forward is economic contraction first, followed by the emerging of some sort of steady state economy. BAU can not and will not continue. To make assumptions based on it will not produce anything of value. Perhaps an economy based on producing very fine and sheer robes for the emperor is what these people have in mind. However, from where I sit, the emperor’s buttocks are not a very appealing sight!

Fred (#11),

Economic growth is to be expected in an energy transition. There is new stuff to make, sell and buy. If you care at all about the climate, you should certainly hope for substantial economic growth.

In these discussions, BAU has the meaning of continued growth in greenhouse gas emissions. It does not refer to economic growth alone, but the associated emissions. This report indicates that cutting emissions can be associate with economic growth so I think you are going to need to dig into the details and show where they are wrong. But, I don’t think you’ll find them down there below the emperor’s outhouse. There is a practical reason he is not wearing pants when you are looking up from there.

mememine69 @~ 13

Bore Hole worthy gibberish?

Michael (#12),

GDP turns out to be a slippery measure for disaster loss. The economic activity of disaster recovery can lead to a GDP gain. http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2011/09/01-disasters-stimulus-baily

I really don’t understand why the IPCC is coming with reports like this. They are worse than useless because the core issue is completely ignored, which means that we are focusing on irrelevant questions. And the core issue is growth itself.

You cannot have infinite growth in a finite system. It’s a simple as that and it does not matter whether it is fossil-fuel based or based on something else:

1. Perpetual motion machines are a physical impossibility.

2. There is the famous Liebig’s law of the minimum, i.e. that the growth of a system is limited by the vital resource that is in least abundance relative to the requirements of that growth.

The whole vast enterprise of the IPCC and all the highly politically charged discussion of climate change is focused on JUST ONE vitally important resource – in this case the capacity of the planet’s atmosphere to absorb our waste. But there are dozens of others the limits of which we are on a head-on collision course with – somewhat ironically, fossil fuels themselves, fertile soil, fresh water, a long list of mineral resources, we are completely wrecking the biodiversity and the ecosystems of the planet, and so on and so on.

These are all just different symptoms of the same problem and have the same solution. The problem is that we have a socioeconomic system that is founded on the assumption of infinite growth, and requires it for its continued existence, and the solution is to dismantle that system and replace with a steady state system (of much smaller absolute size). Otherwise there can be only one outcome and it is only a question of which resource limit (or combination of) will cause the collapse of civilization first.

So why is the IPCC talking about how it is going to be cheap to tackle climate change on the scale of the projected future economic growth when they should be talking about how that growth should never happen in the first place? It will not happen anyway – the system will collapse long before the economy grows tenfold relative to its current size, the resources simply aren’t there. There are hard physical limits to efficiency – it takes a minimum amount of energy to move an object from point A to point B – while economic growth is exponential and never ending.

I understand the political situation – if the IPCC did in fact come out with a “end economic growth” message, that would be completely politically unacceptable and will only feed into the anti-science propaganda on the other side. But by not doing that, the outcome is not going to be any good either – at least try to start the conversation…

In many ways, I wish the IPCC would not succumb to the urge to address issues e.g. the law, governance or ethics, because it usually does a bad job, as it did here. There’s an incredible wealth of literature that has developed around this topic, and the IPCC manages to distill very little of it. and not very well. Stick to your core mission, IPCC, unless your heart is really in it, in which case, you need to bring in a broader swath of stakeholders to prepare sections of this genus.

Killian says:

17 Apr 2014 at 3:03 PM

(Looking for, but cannot find, a recent article in which a climate scientist talks about massively reduced consumption.)

Unfortunately, it is not just consumption, there is also population, an even less popular topic…

Gavin, a very highly moderated thread could help maintain focus here.

Dr. Knopf, thank you, please stay with us.

One question that occurred to me on first reading your first posted draft was about Greenland — you wrote “risks with low probability but high impacts (e.g. melting of Greenland ice-sheet)”

I see that on your rewrite a few minutes later you instead use low lying islands as the example for that kind of risk.

I’m guessing sea level rise seems more predictable over the next few centuries and part of the larger report.

Is Greenland not a good example for low probability high impact because the eventual impact, even if more probable in the long term, falls beyond the time horizon considered in this report?

I recall

http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v2/n6/abs/nclimate1449.htmlhas some time estimates.From the main post: “Many models could not achieve atmospheric concentration levels of about 450 ppm CO2eq by 2100…”

Aren’t we already close to 450 ppm CO2eq already?

Do these models include any carbon feedbacks?

11 Chris Dudley: Nuclear power is off topic.

@Killian, Kevin Anderson of Tyndall Centre and University of Manchester has written and spoken about the need for massive demand-side reductions many times, often with his colleague, Alice Bows. See https://vimeo.com/62871951. There are probably others.

@5, @6, @16 on cost metrics:

Anybody who is interested to learn more about the different cost concepts used for mitigation, e.g. about the difference between GDP and consumption, here is a very good overview of cost concepts for climate change mitigation by MIT and IPCC author Paltsev et al.:

http://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/10.1142/S2010007813400034

Comment by mememine69

Liberty University Grad?

Brigitte (and others),

Thanks for the response. From what you say, it sounds as though when people like Lomborg (for example) quote some numbers out of WGII and then compare then with some numbers out of WGIII, they are – at best – making comparisons that don’t really make sense. Is that a fair conclusion?

@23

Concerning your question on 450ppm CO2eq. We are today at a concentration of about 400ppm CO2 only, but not CO2-eq (equivalent).

In the SPM WGIII they give a reference for 2011:

“For comparison, the CO2eq concentration in 2011 is estimated to be 430 ppm (uncertainty

range 340–520 ppm) footnote13.

Footnote 13: This is based on the assessment of total anthropogenic radiative forcing for 2011 relative to 1750 in WGI, i.e. 2.3 W m‐2, uncertainty range 1.1 to 3.3 W m‐2. [WGI AR5 Figure SPM.5, WGI 8.5, WGI 12.3]” (SPM WGIII).

@28

I cannot comment on what Lomborg says or compares. But indeed many non-experts who are comparing the numbers of WGII and WGIII are comparing apples with pears. There is no direct comparison possible with the numbers and the metrics given in both reports.

@22

The first post was by accident, so it didn’t mean that melting of the Greenland Ice-sheet is not a big risk, indeed it is. But examples like Santa Lucia or the Maldives are very prominent in this respect, also in the UNFCCC negotiations, because how much do you weight the risk that hundreds of people lose their homes?

From the main post: “Probably not everyone likes to hear that CCS is a very important technology for keeping to the 2-degree limit and the report itself cautions that CCS and BECCS are not yet available at a large scale and also involve some risks.”

So if the projections that say we can easily stay below 2 degrees all require massive deployment of technologies that, generously stated “are not yet available at a large scale,” how much are such plans different than relying pixie dust?

The whole program strikes me as shockingly disingenuous. I would dearly like to hear what the site administrators here thing of it. Did they post it because the judge it to be a valid assessment of the real possibilities? Or just because it was put out by the IPCC, is widely reported on, and so is worthy of discussion?

Georgi (#19),

Growth at 2% for 35 years doubles the economy, which is far short of a ten-fold increase. Surely, you would not begrudge the economic prosperity that under-girds demographic models of stabilized world population?

Edward (#24),

Look at Table SPM 2. It appears to be on topic.

[edit – no. Nuclear is always off topic here. It never goes anywhere and no-one leaves any the wiser. Take your discussions on that to Barry Brooks site.]

An excellent layperson’s introduction to the issues involved here – to integrated assessment models, cost-benefit analyses, discount rates, carbon prices and so forth – is William Nordhaus’ The Climate Ca#ino. There are a lot of popular books on the science and politics of global warming, but not so many on the economics. (Note, I’ve had to misspell a word in the title and use tinyurl to get this past the spam filter.)

Edward Greisch wrote (#24): “Chris Dudley: Nuclear power is off topic.”

But, Edward — just a few comments earlier, you linked to a lengthy article from the pro-nuclear advocacy site, Brave New Climate, which critized the WG III report for an alleged “double standard in how IPCC depicts problems with nuclear versus renewable energy”.

But then when Chris Dudley posts a comment addressing that very topic — a comment which is skeptical of the point of view you linked to earlier and may well have been prompted by that link — you declare that “nuclear power is off topic”.

Which seems like a bit of a double standard.

Perhaps you should say what you have to say about the WG III report, and leave it to the moderators to say what’s off-topic and what’s not.

Brigtte (#26),

Thanks for the link. I notice this statement: “Decarbonization of power generation implies higher costs per unit of output compared to a base case, as carbon-free generation is more expensive than conventional generation.”

Interestingly, Germany in particular, has noticed that economies of scale have not yet been fully exploited for “carbon-free generation” and thus there is room to cut costs. Thankfully, owing in part to their efforts to prime the pump on this, the statement in your link no longer seems to be valid. http://cleantechnica.com/2014/03/13/solar-sold-less-5%C2%A2kwh-austin-texas/

Costs are anticipated to fall further.

On a pedantic note, fossil fuel costs have rarely been lower than hydro electric costs so in one sense carbon-free generation has generally been less expensive than conventional generation.

Editor @33,

I thought is was the jawboning about unconventional nuclear technologies that was considered pointless. More up-to-date costs estimates than available to the IPCC for the technologies they considered would seem to be an important aspect in evaluating the present report since that is the big take-away from it. If the sixth entry in Table SPM 2. has the wrong sign, that may have policy consequences. Relative costs of energy sources seems to be one of the core topic of this post.

And, it is brought forward by the author as well: “…the costs are not only shown for the case when all technologies are available, but also how the costs increase if, for example, we would dispense with nuclear power worldwide or if solar and wind energy remain more expensive than expected.”

Present market information, such as Austin Power’s purchase of solar power for less that $0.05/kWh and Excelon statements about plant closures owing to competition from wind energy suggest that these features of the report may not be helpful. http://www.platts.com/latest-news/electric-power/lasvegas/power-price-recovery-may-be-too-late-to-aid-its-21452315

It has been noted frequently that IPCC reports are necessarily out-of-date in some areas owing to rapidly evolving research not matching their deliberative timescale. Markets also have momentum, and are shifting more rapidly where innovation is involved. Bringing to light areas where the deliberative process may be impeding presenting the most complete picture possible (absent such time delays) would seem to be a very important function of this type of discussion.

Brigtte (#30),

The IPCC has been issuing more frequent interim reports. Do you think an methods reconciliation between WG II and WG III on this point might be forthcoming in a year or two?

2 Davos:

As with “skeptic”, anybody can call themselves an environmentalist, and nobody owns the word. FWIW, if I’m up against a wall I say I’m a Conservationist, because Homo sapiens isn’t the only species occupying the Earth.

IMO the threat posed by climate change doesn’t justify ignoring the externalities associated with renewable energy production. Political labels notwithstanding, if “environmentalism” means anything, it means acknowledging that all the costs of economic prosperity are paid by someone, somewhere in the biosphere, at some time. Does anyone here (excepting the troll-bot ‘nymed mememine69, perhaps) really want to argue with that?

Since the growing world economy is such a major contributor to the release of greenhouse gases, should it mean that production of those products that release carbon emissions be slowed down or completely terminated, or should the cost of these products increase as a result of the implementation of so-called new eco-friendly methods of production?

Note, the inline comments usually have a green font that is missing at #33, so — mentioning that’s there.

Chris Dudley says:

18 Apr 2014 at 9:05 AM

Georgi (#19),

Growth at 2% for 35 years doubles the economy, which is far short of a ten-fold increase. Surely, you would not begrudge the economic prosperity that under-girds demographic models of stabilized world population?

1) 2% growth is not something economists would be very happy about

2) 3% growth increases the size of the economy 13-fold between now and 2100

3) How much growth is sufficient? At some point you have to stop, do you disagree with that (again, perpetual motion machines do not exits)? If you don’t, then when is that point? And do you see the current system as being capable of saying “enough”? I don’t – it is founded and dependent on perpetual expansion.

4) The demographic projections that have the world’s population stabilizing are founded on the completely false assumption that people will get rich and then have fewer kids. People are not going to get rich because the resources for that to happen are not there. Conventional oil production has already peaked, for example. You can therefore throw away those projections as largely meaningless.

5) The current world population is completely unsustainable as it is, and so is the economy. That it might stop growing at 10 billion is of absolutely no comfort when we are already deeply unsustainable at 7.

George Marinov @19

“I really don’t understand why the IPCC is coming with reports like this. They are worse than useless because the core issue is completely ignored, which means that we are focusing on irrelevant questions. And the core issue is growth itself.

You cannot have infinite growth in a finite system. It’s a simple as that and it does not matter whether it is fossil-fuel based or based on something else …”

The IPCC is operating within a long established economic framework, that is, growth economies. Were they to exceed that bound and introduce the idea of a steady-state or no growth) form of economy, they would be risking any acceptance of their scientific findings and widespread an very serious criticism for doing so.

Advocating a steady-state form of economy is indeed a legitimate advocacy to undertake and more of us should be doing so, there seems to be little doubt about it. The now defunct British Sustainability Commission did a good job of this and published an excellent report in 2009, “Prosperity without Growth,” which you can find on the web using Google.

But it’s an idea whose time has not yet come, and it might well get swamped in the sure-to-come uproar over the next few years about reducing emissions, which is most likely to make what we’ve seen so far pale in comparison. This may be hrd to imagine, but when the beast’s back is put up against the wall, it’s probably going to react in wildly unexpected and severe ways.

Don’t put the cart before the horse, and don’t worry too much about how reports such as are the topic here get in the way of the debate we really need to be having. If nothing else, they’ll reveal the futility of trying to squeeze modern science into an antiquated and quite obsolete 17th century economic paradigm.

When staring at an edifice that’s as entrenched as growth economics, patience is called for. It’ll go soon enough and a steady-state economic schema will likely be at the center of any successful effort to bring emissions down to a level the world can live with.

The status quo proves daily it isn’t a viable vehicle through which we can achieve the desired outcome. The sooner we admit this the better. But we’ve not quite arrived at that point yet. Give it another five or eight years, it’ll become the talk of the town and climate science will be heaving an enormous sigh of relief.

Seems to me that the IPCC reports remain highly politicized (and therefore unrealistic), presumably to increase acceptability.

To effectively wean the world off fossil fuel by, say, 2080 would require 6% per year reductions in carbon emissions beginning immediately. In the absence of safe effective carbon dioxide sequestration or assimilation technologies, this implies abandoning fossil fuels at a rate up to 6% yr. Obviously, to maintain current levels of energy supply this, in turn, implies the substitution of viable alternative energy sources at a corresponding rate.

Unfortunately, available renewable energy sources (excluding hydro) are inadequate substitutes for many uses of fossil fuel and, at present, they barely supply energy equivalent to the (mostly fossil) energy consumed in producing the alternative technologies themselves. Indeed, according to some comprehensive life-cycle analyses, certain sources of biomass energy are net energy sinks (and sources of carbon emissions). This is one reason why renewable alternatives currently make up less than 3% of the global energy budget and most analyses don’t see them reaching much more than 6% by 2030 (Hydro makes up another 6%, leaving us over 85% dependent on fossil fuels or nuclear ).

In any case, in the real world, fossil fuel use and carbon emissions continue to increase at 2-3% per year.

In this light, doesn’t the IPCC cost-of-mitigation/adaptation estimate of just a .6% loss in GDP growth seem just a tad naive? Is there any politically acceptable scenario by which the world can hold the line at just two Celsius degrees of warming (which, according to some analysts, should actually be just one degree) without significant reductions in gross energy consumption and the massive economic reconstruction (chaos?) and geopolitical tension this implies?

Of course, if there isn’t such a scenario, then we are condemned to escalating climate disruption (chaos again).

This is an archetypal case of being ‘between a rock and a hard place’. It suggests that the world should be contemplating the possibility that the short-lived fossil fuel-funded era of growth is over and planning a deliberate contraction toward a smaller, more equitable, steady-state economy within the means of nature.

Perhaps the next IPCC assessment report will take this on.

I am a reasonably intelligent person, probably better educated than most local and state politicians. I find the sheer complexity of the IPCC reports to be daunting. Even in discussions with like minded (concerned “believers” in AGW) people, there is incredibly wide variation in understanding of the science behind climate change and the nature and timing of potential consequences.

In my US state (red/coal) 95% of our energy is coal fired, nuclear is not allowed, and growth and development is based on conventional business models.

“…scientists are mapmakers that will help policymakers to navigate through this difficult terrain in this highly political issue of climate change. And this without being policy prescriptive about which pathway should be taken or which is the “correct” one. This requirement has been fulfilled and the map is now available. It remains to be seen where the policymakers are heading in the future.”

Policy in my state will not change significantly in the next 20 years barring some catastrophe. My state is not unique. It is therefore up to the federal government to make policy. What’s the chance of action there? IPCC needs to prepare AR5 for dummies.

Georgi (#39),

You are a doomer. And, oil is the thing on which you are hinging that position. All I can say is don’t worry, be happy! http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/d-brief/2014/04/08/u-s-navy-can-convert-seawater-fuel/

It may be that economic growth cannot carry on indefinitely, though with more and more of it happening in a virtual world, that is not at all clear. But, your demarcation of where it must stop seems disproved by it already having happened passed that point.

Let’s hope that everyone in the world can find sufficient freedom from want to allow them to let their daughters and sons to be educated.

William E. Rees wrote: “… available renewable energy sources (excluding hydro) are inadequate substitutes for many uses of fossil fuel and, at present, they barely supply energy equivalent to the (mostly fossil) energy consumed in producing the alternative technologies themselves”

Neither of those statements are true.

Far from being “inadequate” compared to fossil fuels, the solar energy alone that we receive in one year — every year — is orders of magnitude greater than ALL the energy containted in all the fossil fuels and uranium on Earth. Likewise the energy available from wind every year is far greater than the energy contained in all the world’s supplies of fossil fuels and uranium.

And the payback time on energy invested in building and deploying renewable energy technologies (e.g. solar panels and wind turbines) is a fraction of their productive lifetime.

William E. Rees wrote: “… renewable alternatives currently make up less than 3% of the global energy budget and most analyses don’t see them reaching much more than 6% by 2030.”

Again, this is incorrect. According to the International Energy Agency’s very conservative projection:

I recommend reading “Renewables 2013 Global Status Report” (PDF download) from The Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (REN21).

Humanity does indeed face some daunting and perhaps insurmountable challenges, but obtaining an abundant and endless supply of clean energy is not one of them.

William (#41),

I think there is a problem with you’re numbers. A chunk of about 1.5% of present fossil fuel use must be cut each year to get to zero emissions by 2080, not 6%. Perhaps the year is a typo?

And, beyond that, your logic is a bit circular. If you complain that we must replace a large energy source with an alternative, but all the alternatives are small, might they not be small just because of the way you’ve posed the problem? I mean, if we had to replace horses with oil and the only oil came from whales, would that really be a reason to panic?

William E. Rees @41

“Seems to me that the IPCC reports remain highly politicized (and therefore unrealistic), presumably to increase acceptability.”

Anything that needs the signatures of 199 countries to be approved for publication will probably have to be rather conservative in nature and in the case of climate science this means understating the case.

While I presume there would be a grain of truth in an interpretation that characterized this as being “highly politicized” it would only be a grain, certainly not the whole truth.

“To effectively wean the world off fossil fuel by, say, 2080 would require 6% per year reductions in carbon emissions beginning immediately. In the absence of safe effective carbon dioxide sequestration or assimilation technologies, this implies abandoning fossil fuels at a rate up to 6% yr. Obviously, to maintain current levels of energy supply this, in turn, implies the substitution of viable alternative energy sources at a corresponding rate.”

In early 1942, the Congress enacted legislation that was known as “Total Conscription,” which conscripted nearly the entire economy to the war effort. Economic activity that didn’t contribute to the war effort was effectively made illegal.

Now, movies were made and major league sports were played and Broadway plays were produced, which hardly would seem to be contributory to a “war effort.”

However, there was a rationale, these activities were deemed to be supportive of both the public’s and the armed force’s morale; but just try to do economic activity that could not be so rationalized and which didn’t contribute to the war effort in some direct or tangible way, and it was no dice, you could be prosecuted, and some were.

This was done because the nation faced an unprecedented threat, one that our leaders of the day knew would require every last ounce of productivity the nation could muster if it hoped to defeat the threat the country faced.

Fast forward to sometime in the 2020s when the country will be facing yet another unprecedented threat, that of a deteriorating climate, with a continuing string of insidious and damaging weather events, extended periods of record setting drought, periods of inundation from way above normal rainfall and the floods that attend, and heat waves that will make Texas 2010-2011 look like a Sunday picnic … and prognostications that it’s all only going to keep getting worse, and you have a situation that’s eerily and worryingly analogous to January, 1942.

What happens then?

UN SECGEN Ban ki Moon said it a couple of years ago, “we’ll have to go to a war footing.”

After more than 25 years of trying to get emissions reduced in what amounts to an utterly uncontrolled and uncontrollable economy and coming up empty, we may wake up to find ourselves facing a war footing as the only means left to reduce emissions to levels that won’t push Earth’s mean annual average temp over 3 or 4C above the preindustrial norm.

This point is lost on most of us today; we can’t imagine what it will be like when we’re finally forced to face the music, forced by physics and atmospheric dynamics and behavior. Few people in November, 1941 thought for a moment that global war was going to erupt and change their lives forever. It was unthinkable. Total conscription? Bah humbug.

But it happened anyway. Sometimes the unthinkable is what we have to do; we simply cannot allow our world’s temperature to increase beyond “X” level and sacrifice civilization on the alter of growth economies. Especially when there are better ways, ways that will be brought into the sunlight when we find our backs against the wall and it has become a truly do or die situation.

Extraordinary circumstances require extraordinary action.

“In any case, in the real world, fossil fuel use and carbon emissions continue to increase at 2-3% per year.

In this light, doesn’t the IPCC cost-of-mitigation/adaptation estimate of just a .6% loss in GDP growth seem just a tad naive? Is there any politically acceptable scenario by which the world can hold the line at just two Celsius degrees of warming (which, according to some analysts, should actually be just one degree) without significant reductions in gross energy consumption and the massive economic reconstruction (chaos?) and geopolitical tension this implies?”

It’s only implied when you think inside the box.

“Of course, if there isn’t such a scenario, then we are condemned to escalating climate disruption (chaos again).”

The question is, will the world tolerate chaos, or chose a more enlightened way?

“This is an archetypal case of being ‘between a rock and a hard place’. It suggests that the world should be contemplating the possibility that the short-lived fossil fuel-funded era of growth is over and planning a deliberate contraction toward a smaller, more equitable, steady-state economy within the means of nature.”

A steady-state economy would result in an enormous reduction in the consumption of resources (by eliminating the enormous wastes that are inherent in a growth economy. i.e., a consumer-driven economy), with a corresponding increase in standards of living. Quality instead of quantity.

“Perhaps the next IPCC assessment report will take this on.”

Or, more likely, some other body will.

We need not be too concerned about China or India or Brazil, they’ll be freaking out too and will most likely follow our lead.

None of us should discount what can be done when the handwriting’s emblazoned on the wall in stark neon colors. Besides, it’s time we got rid of our antiquated form of economy anyway. It certainly isn’t serving us very well, now, is it? No, it isn’t.