The second part of the new IPCC Report has been approved – as usual after lengthy debates – by government delegations in Yokohama (Japan) and is now public. Perhaps the biggest news is this: the situation is no less serious than it was at the time of the previous report 2007. Nonetheless there is progress in many areas, such as a better understanding of observed impacts worldwide and of the specific situation of many developing countries. There is also a new assessment of “smart” options for adaptation to climate change. The report clearly shows that adaptation is an option only if efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions are strengthened substantially. Without mitigation, the impacts of climate change will be devastating.

Guest post by Wolfgang Cramer

On all continents and across the oceans

Impacts of anthropogenic climatic change are observed worldwide and have been linked to observed climate using rigorous methods. Such impacts have occurred in many ecosystems on land and in the ocean, in glaciers and rivers, and they concern food production and the livelihoods of people in developing countries. Many changes occur in combination with other environmental problems (such as urbanization, air pollution, biodiversity loss), but the role of climate change for them emerges more clearly than before.

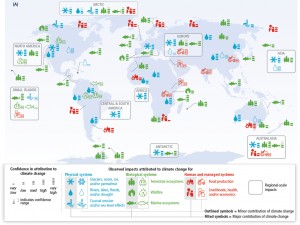

Fig. 1 Observed impacts of climate change during the period since publication of the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report 2007

During the presentation for approval of this map in Yokohama many delegates asked why there are not many more impacts on it. This is because authors only listed those cases where solid scientific analysis allowed attribution. An important implication of this is that absence of icons from the map may well be due to lacking data (such as in parts of Africa) – and certainly does not imply an absence of impacts in reality. Compared to the earlier report in 2007, a new element of these documented findings is that impacts on crop yields are now clearly identified in many regions, also in Europe. Improved irrigation and other technological advances have so far helped to avoid shrinking yields in many cases – but the increase normally expected from technological improvements is leveling off rapidly.

A future of increasing risks

More than previous IPCC reports, the new report deals with future risks. Among other things, it seeks to identify those situations where adaptation could become unfeasible and damages therefore become inevitable. A general finding is that “high” scenarios of climate change (those where global mean temperature reaches four degrees C or more above preindustrial conditions – a situation that is not at all unlikely according to part one of the report) will likely result in catastrophic impacts on most aspects of human life on the planet.

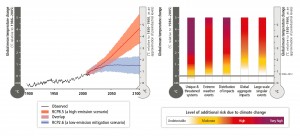

Fig. 2 Risks for various systems with high (blue) or low (red) efforts in climate change mitigation

These risks concern entire ecosystems, notably those of the Arctic and the corals of warm waters around the world (the latter being a crucial resource for fisheries in many developing countries), the global loss of biodiversity, but also the working conditions for many people in agriculture (the report offers many details from various regions). Limiting global warming to 1.5-2.0 degrees C through aggressive emission reductions would not avoid all of these damages, but the risks would be significantly lower (a similar chart has been shown in earlier reports, but the assessment of risks is now, based on the additional scientific knowledge available, more alarming than before, a point that is expressed most prominently by the deep red color in the first bar).

Food security increasingly at risk

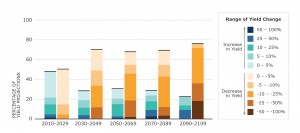

In the short term, warming may improve agricultural yields in some cooler regions, but significant reductions are highly likely to dominate in later decades of the present century, particularly for wheat, rice and maize. The illustration is an example of the assessment of numerous studies in the scientific literature, showing that, from 2030 onwards, significant losses are to be expected. This should be seen in the context of already existing malnutrition in many regions, a growing problem also in the absence of climate change, due to growing populations, increasing economic disparities and the continuing shift of diet towards animal protein.

Fig. 3 Studies indicating increased crop yields (blue) or reduced crop yields (brown), accounting for various scenarios of climate change and technical adaptation

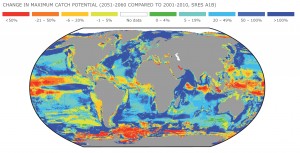

The situation for global fisheries is comparably bleak. While some regions, such as the North Atlantic, might allow larger catches, there is a loss of marine productivity to be expected in nearly all tropical waters, caused by warming and acidification. This affects poor countries in South-East Asia and the Pacific in particular. Many of these countries will also be affected disproportionately by the consequences of sea-level rise for coastal mega-cities.

Fig. 4 Change in maximum fish catch potential 2051-2060 compared to 2001-2010 for the climate change scenario SRES A1B

Urban areas in developing countries particularly affected

Nearly all developing countries experience significant growth in their mega-cities – but it is here that higher temperatures and limited potential for technical adaptation have the largest effect on people. Improved urban planning, focusing on the resilience of residential areas and transport systems of the poor, can deliver important contributions to adaptation. This would also have to include better preparation for the regionally rising risks from typhoons, heat waves and floods.

Conflicts in a warmer climate

It has been pointed out that no direct evidence is available to connect the occurrence of violent conflict to observed climate change. But recent research has shown that it is likely that dry and hot periods may have been contributing factors. Studies also show that the use of violence increases with high temperatures in some countries. The IPCC therefore concludes that enhanced global warming may significantly increase risks of future violent conflict.

Climate change and the economy

Studies estimate the impact of future climate change as around few percent of global income, but these numbers are considered hugely uncertain. More importantly, any economic losses will be most tangible for countries, regions and social groups already disadvantaged compared to others. It is therefore to be expected that economic impacts of climate change will push large additional numbers of people into poverty and the risk of malnutrition, due to various factors including increase in food prices.

Options for adaptation to the impacts of climate change

The report underlines that there is no globally acceptable “one-fits-all” concept for adaptation. Instead, one must seek context-specific solutions. Smart solutions can provide opportunities to enhance the quality of life and local economic development in many regions – this would then also reduce vulnerabilities to climate change. It is important that such measures account for cultural diversity and the interests of indigenous people. It also becomes increasingly clear that policies that reduce emissions of greenhouse gases (e.g., by the application of more sustainable agriculture techniques or the avoidance of deforestation) need not be in conflict with adaptation to climate change. Both can improve significantly the livelihoods of people in developing countries, as well as their resilience to climate change.

It is beyond doubt that unabated climate change will exhaust the potential for adaptation in many regions – particularly for the coastal regions in developing countries where sea-level rise and ocean acidification cause major risks.

—

The summary of the report is found here. Also the entire report with all underlying chapters is online. Further there is a nicely crafted background video.

Wolfgang Cramer is scientific director of the Institut Méditerranéen de Biodiversité et d’Ecologie marine et continentale (IMBE) in Aix-en-Provence one of the authors of the IPCC working group 2 report.

Weblink

Here is our summary of part 1 of the IPCC report.

CORRECTION:

In my most recent comment, I state at one point:

This should have been omitted — as should be my later reference to the same paper. While they are closely related, the issues of the lifetime of CO2 and the lifetime of atmospheric warming are distinct. While CO2 concentrations and thus radiative forcing due to CO2 begin to fall immediately after emissions drop to zero, temperature does not appreciably fall — as the reduction in radiative forcing is balanced by the reduction in heat uptake by the ocean, per:

Chris Dudley #98,

“So, Gavin gave you two links. I think perhaps if you understood that I am speaking of stopping emissions all at once, just as Gavin’s links explore, you would understand my statement better”.

I understand that you want to stop emissions all at once; that has been the focus of my posts on this thread. Gavin provided two links. The first link was – how shall I say it – incomplete. In the second link, Gavin described the first link thusly: “however, as a few people pointed out in the comments, this exclusive focus on CO2 is a little artificial…..Thus, I shouldn’t have neglected to include these other factors in discussions of the climate change commitment.”

I suspect the authors of the Letter did not include aerosols in their analyses. Aerosols are short-lived, and if all fossil fuel combustion were terminated immediately, essentially all the aerosols would precipitate, and their shielding of the sun would vanish, leading to increased temperatures. If one allows the aerosols to remain in the atmosphere under the immediate CO2 cessation case, as I assume the authors of the Letter did, then, yes, the temperature would not increase. What kind of physics would that be? It seems to me you are distorting the science to promote your pre-determined China-bashing agenda.

Timothy (#100),

Nice digging. I think that you would agree with me that all delta function emissions profiles that have ever been examined lead to warming then cooling to a temperature above the initial temperature. Thus my statement that we can construct profiles with this type of behavior is manifestly true. Then the question is, has our initial build up been steep enough to allow this for an immediate cut. But, the actual criteria is not cooling but a lack of warming.

From what you’ve summarized, ending emissions suddenly does not result in a final temperature higher than the current temperature so future greenhouse warming depends on future emissions, not past emissions. Note that the use of the word “final” here is important as it is above, where you feel you see a contradiction that does not exist.

I don’t think we have a disagreement that some climate change is irreversible (modulo capture and sequestration of carbon dioxide through, for example, modified agricultural practices). I do think that AR5 indicates that the irreversible consequence of mass species extinction can be avoided and suggests we can pull back from the current dangerous climate change that we are experiencing as might be expected from Fig. 4 here: http://edoc.gfz-potsdam.de/pik/get/5095/0/0ce498a63b150282a29b729de9615698/5095.pdf

DIOGENES (#102),

I don’t want to stop emissions all at once, I want to know if a WTO case can be made that placing tariffs on Chinese imports to the US is allowed under the GATT without a long time delay. One possible quarrel to eliminate is that China’s emissions don’t matter because inertia from vast historical emissions means that all future warming is our fault. Many people here seem to feel that that is the case. The science does not support it.

Timithy (#100),

Sorry, I missed this: “Effectively (per Matthews and Caldeira), even when the rate of emissions go to zero, what determines future temperatures for the foreseeable future are total cumulative emissions, and as such, a kilogram of CO2 emitted a century ago contributes to future warming just as much as a kilogram of CO2 emitted today or five decades from now.”

If we end emissions now, there won’t be any kilogram emitted 5 decades from now. And the temperature five decades from now would be lower than if we had carries on emitting for five decades. So, it seems that at least some future warming depends on future emissions. Would you not agree with that? After all, future emissions contribute to cumulative emissions as you say, unless there are no future emissions.

Hank (#94),

You seem to have missed a rather important aspect of this situation. The latecomer is being offered the most delightful cake as an alternative owing to research sponsored in the Carter administration. The latecomer does not have to suffer all the horrible drawbacks of the fossil fuel spinach we were forced to eat. They can go directly to the renewable energy desert. The situation is even more generous than the Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard considering that the tardiness was self-inflicted through horrible human rights abuses perpetrated on the educated citizens simply for having an education.

Now, you should really give a few more reads to what I’ve written because you have again put words is my mouth that I did not say. For example, on overshoot, since I continually note that dangerous climate change has come sooner than expected, the essential reason why future emissions growth is intolerable, overshoot is not only acknowledged, it is motivating. I am pleased that RCP2.6 can avoid some of the irreversible consequences of climate change according to AR5. There are various thresholds for overshoot. Perhaps you are thinking that there is just one.

#95–Thanks for the clarifications.

Just a few (though, sadly, somewhat lengthy) comments. I’m going to break them up, largely in an attempt to deal efficiently with the spam filter, which doesn’t like something…

You say:

I think you will look in vain for any Party ‘crying mea culpa’ in the context of negotiations which involve the economic future of their nation. However, the whole structure of Annex I and the rest makes pretty clear that there is (or has been) broad acceptance of the principle that the ‘responsibility’ of developed nations for historical emissions is primary. Moreover, the results of Warsaw suggest a tentative (and rather weasel-worded) acceptance of the idea that rich nations should be responsible for damages from warming:

http://unfccc.int/adaptation/workstreams/loss_and_damage/items/8134.php

Kinda sounds like liability…

“It seems to me you are distorting the science to promote your pre-determined China-bashing agenda.”

And put his WTO argument in a box in the process – if future emissions only are the driver of change, anyone emitting any amount is at fault, not one particular country, regardless of “intentions”.

Comment Part Deux

But I’m not talking primarily about the legalisms. I’m talking about the politics. My perception–for what that is worth–is that thorough-going adoption of the point of view you’ve been expressing would be extremely provocative, and would be tantamount to repudiation of the structure that exists. Frustrating and ineffective as the process has been lately (meaning, ‘at least since 2009’), I think that its complete failure would really be a Bad Thing.

You say:

Well, I must disagree in a couple of ways. I still feel skeptical about the durability of the US emissions decrease–particularly in light of the fact that there was a ‘negative decrease’ last year. But setting that aside, your statement that China is “not growing their energy sector in a way that cuts emissions” is only true if you add the qualification “right now.”

Let’s review: China has built (in a very short time) the largest renewable energy manufacturing sector in the world, and has deployed more renewables than anyone else. She is undertaking the world’s largest expansion of her nuclear generation capacity as well. While new coal generation capacity is also being added, there has been concomitant retirement of old, inefficient coal plants, with the stated aim of reducing reliance on fossil fuel. Oh, and let’s not forget the mandating of energy efficiency measures, including possible criminal proceedings against non-compiant officials:

http://tinyurl.com/ChinaEnergyEffStory

One can’t argue that all this has stopped the rise of emissions, of course. However, it sure does look like a very serious effort to transform the Chinese energy economy. Despite the putative decrease in US emissions, there is nothing like this kind of commitment in the US. Indeed, some (not necessarily me!) argue that America is locking in yet more reliance upon fossil fuels with current investment decisions:

http://tinyurl.com/ECChinaRenewablesTrajectory

That’s an analysis well worth reading, IMO. “The official target from the NDRC in China is for this proportion to rise to 30% by 2020 – a target that shows every likelihood of being reached.” (Yes, given that the renewable target for the current five year plan (2011-2015) was reached three years early.) Compare also this (Australian) business report, especially Figure 1, which illustrates the EC analysis better than their own graphics.

http://tinyurl.com/BizSpecAUCleantechStory

Comment Part Trois

It’s not clear to me when the increasing proportion of renewables and nuclear is going to result in dropping emissions. Indeed, I doubt it’s clear to anyone–for one thing, no-one seems to have expected the slowdown in Chinese economic growth seen over the last couple of years. But I’m pretty sure it will be well before the 2038 peak shown in the EIA analysis we were talking about above.

Some interesting speculation from the “Energy Collective” analysis above:

Sounds plausible to me–and it raises a larger question. While I’ve argued sort of an “A for effort”–or maybe a “B+”–thesis above, you, Diogenes, and just about everybody else here are of course correct that what we really need form a purely climatic point of view is for emissions to just stop, right now. Not possible, of course–but what is possible for China? How much more could she be doing? I don’t think a thorough-going answer is possible, but it is possible to consider some of the constraints.

First and foremost is political stability. The regime is authoritarian, and deeply inconsistent from an ideological point of view. That means that pragmatic success in handling the economy and social issues becomes paramount, because that’s what lets everyone look the other way with regard to the political justification of the status quo. (Including the quasi-kleptocratic nature of the Chinese elite. Or should that have been “crypto-kleptocratic?” Anyway…)

If your choice were climate disaster in, say, 2050, versus political disaster in 2020 (possibly culminating in your execution at the hands of revolutionaries), what would you choose? The former may be worse for the planet, but the latter would definitely be worse for the ruling elite–many of whom would be dead by 2050, anyway. So there’s clearly a limit there, somewhere.

I do think it’s possible to get China to do more yet, and who knows? A GATT threat might be a useful bargaining chip. But it would be a heck of a lot more useful if the US were less vulnerable to all manner of countercharges (not to mention retaliatory GATT or other trade actions on other grounds–which could probably be cobbled up, if past precedents are worth anything.) And chief among the measures reducing vulnerability would be a US national emissions policy really worthy of the name–one, that is, that had solid Congressional public support. That, in turn, requires a whole lot of organization, education, and political activism, and it requires it ASAP.

Which, FWIW, is what I’m trying to do, despite all the distractions and requirements of quotidian living.

Methodological comment on spam-filter

It was the links in my ‘Part Deux.’ Though they didn’t seem objectionable WRT what the spam message said, that evidently was the issue.

So, if your comment, too, should fall afoul of the filter, you might consider using the tinyurl workaround I used–it was quick and easy. Website here:

http://tinyurl.com

Timothy (#100),

One other question that might help illuminate things: Would you agree that future emissions don’t affect past warming? I ask because if you do agree, then you would seem to be asking for a symmetry for the future that you would not allow for the past.

Diogenes writes in 102:

Actually, as I point out in comment 100, the paper:

… “takes aerosols into account” and shows temperatures rise briefly when emissions are abruptly brought to an end only to quickly fall below what they had been prior to emissions being brought to an end. The real problem with the paper is that it is making use of an unrealistic climate model. It uses a shallow ocean of low heat capacity.

Using a more realistic model, we find that warming due to CO2 is effectively irreversible on the time scale of several centuries. If we consider what this means in terms the warming masked by aerosols, we see that the additional warming that results from past emissions once the aerosols are removed will be with us for centuries — regardless of whether there are future CO2 emissions.

What does this mean in terms of Chris Dudley’s argument?

The conclusion he has been trying to reach is stated in 89:

In terms of the physics, his argument fails spectacularly once one takes into account both the presence of aerosols and the heat capacity of a realistic ocean. Aerosols mask warming due to past CO2 emissions. Remove that mask and that warming that aerosols were masking shows up. But far more importantly, that warming doesn’t disappear any time soon. It is effectively irreversible.

As such, physically, there is little reason to distinguish between past and future emissions. Whether a given amount of CO2 is emitted before or after the cessation of masking due to aerosols, it will be responsible for essentially the same degree warming and this warming will be irreversible on human timescales.

We have known that aerosols mask warming at least since the 1970s. As such we have known that removing the aerosols would result in more warming than we are already seeing. Furthermore, more than half of the CO2 emissions since 1750 were emitted since the mid-1970s. Chris Dudley wrote earlier that “… emissions prior to known damage were innocent if we were surprised by the onset of of dangerous climate change, which we were.” But were we as developed nations actually so surprised? Apparently not, at least not any more than the drunk driver who gets into a car and winds up committing manslaughter. As such I do not find his argument regarding culpability convincing.

However, I believe the issue of irreversibility is far more important than that of culpability. Warming due to CO2 emissions is effectively irreversible. It will be with us for centuries. Moreover, aerosols have masked some of the warming due to CO2 emissions. Once that mask is removed we will see additional warming, and that warming will likewise be with us for centuries.

Contrary to Hare and Meinshausen (2006), warming is effectively irreversible. If we care about future generations we need to bring emissions under control as quickly as possible. They cannot afford the legacy we are creating.

Timothy at #105: “In terms of the physics, his argument fails spectacularly once one takes into account both the presence of aerosols and the heat capacity of a realistic ocean. ”

Thanks for that clear evaluation. You do a good job of discussing the aerosol situation. Could you elaborate a bit more on what you mean by “the heat capacity of a realistic ocean” and the role it is likely to play in future warming?

Do you just mean the heat itself coming back to bite us (as it seems more and more likely to do soon with El Nino seeming to develop in the next few months)?

Or do you mean that a hotter ocean will be ever less able to absorb CO2? Are there any recent estimates of when that point will come (when the ocean becomes too hot to absorb CO2 and start emitting it), given the path we’re on?

http://keelingcurve.ucsd.edu/how-much-co2-can-the-oceans-take-up/

Ask, and ye shall receive! Thanks for the great link, Hank (@#115). For those of you who have made the grievous error of not clicking on and reading all of Hank’s posted links, here are a few choice, relevant points:

“…although the oceans presently take up about one-fourth of the excess CO2 human activities put into the air, that fraction was significantly larger at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. That’s for a number of reasons, starting with the simple one that as one dissolves CO2 into a given volume of seawater, there is a growing resistance to adding still more CO2…”

“in the absence of such warming, ocean mixing would normally be expected to be constantly refreshing the water at the ocean’s surface, the place where it meets with air and dissolves CO2. Instead global warming leaves surface water in place to an increasing degree thus slowing down the transfer of CO2 from the ocean surface deeper into the ocean. It’s as if the pump removing CO2 from the atmosphere into the surface water and then on deeper into the ocean had slowed down.

This slowing of ocean mixing may have another effect. It stifles the transport of nutrients such as nitrate and phosphate from deeper waters to the surface, which diminishes the growth of phytoplankton, which store carbon in their tissue as a product of photosynthesis. The sinking tissue takes the carbon with it to the deep ocean when the organisms die. It’s another way that carbon can be removed from the ocean surface.”

Kevin (In three parts),

Yes, that is thoughtful. I would say that I am interested in the immediate cessation of emissions in order too understand what causes future warming. It is a “How does it work?” question. I’m pushing for RCP2.6 as described in AR5 because it is consistent with the goals of 350.org. The 350.org goals are based on a paper about what the target carbon dioxide concentration should be to avoid problems like losing big parts of the WAIS and the GIS. It is now a world organization that grew out of an effort to get the US to commit (without negotiations) to an 80% cut in emissions by 2050. We did not get it from Congress but this administration has made it a goal at least. The people-tech involved in this has probably influenced the outcome of some elections as well. In any case, RCP2.6 still has another 270 GtC of emissions to go. It does not end emissions all at once.

So, you ask the question on which RCP2.6 hinges: “but what is possible for China? How much more could she be doing?”

And, from the GATT perspective, the answer is easy: how much less could China be doing? Does such a vast amount of trade serve us well if it increases emissions? It does not, so use tariffs to reduce the volume of trade until China reassess its policies. Just reducing the trade cuts emissions. If reduced trade threatens the political viability of the leadership, then new leadership can fix the emissions problem. They may be hard to find; China keeps massacring it bravest souls. But somewhere there must be someone like Sun Yat Sen who believes China must be China and not some sad imitation of a defunct prison state.

Well, in terms of rapid climate action, we need to work with what we have. GATT seems like a strong tool.

Is folly in the filter?

wili wrote in 113:

Heat capacity is simply a measure of the amount of energy required to raise the temperature of an something by a given amount. Matthews and Caldeira state:

This is similar to what Tamino dealt with in Spencer’s Folly, parts I through III, accessible from here. In Tamino’s case, he was examining what happens when the forcing is held constant, e.g., where CO2 concentrations are increased from the original value that the system had when it was in equilibrium to a higher value. This differs somewhat from Matthews and Caldeira, in that they allow atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide to fall naturally as carbon dioxide is absorbed by various sinks, but otherwise things are much the same.

In this context Tamino asks essentially how quickly the system approaches a new equilibrium temperature in response to the constant forcing. The answer is… it depends: how deep is the ocean? The deeper the ocean the longer it takes for the ocean to reach a state of thermal equilibrium. The forcing is measured in watts per meter squared per degree Kelvin. That remains the same regardless of how deep the ocean is. But the deeper the ocean the greater the amount of water that is included in a meter squared column, thus the more slowly the system approaches equilibrium.

The difference between current temperature and final temperature falls as an exponential function of time according to a characteristic time scale. For each period of time equal to the characteristic time scale the temperature difference drops by 63% = 0.63, which is 1-(1/e). In essence this is a form of exponential decay. The characteristic time scale is itself proportional to the inverse of the ocean depth. As Tamino calculates it, the characteristic time scale for 50 meters is roughly 1.6 years but for 1000 meters the characteristic time scale becomes 32 years.

However, things get a bit more complicated for Matthews and Caldeira. Not only are they allowing carbon dioxide to be absorbed by a carbon sinks or “pools” but they are allowing for different functions that govern the rates at which carbon moves from one pool to another. The physics of the system determines those rates. They are also allowing for not just 1 but 19 different layers to the ocean, letting physics determine the rate at which each layer warms. They are allowing for ocean circulation. And they are allowing for the fact that the warmer the ocean is the more slowly it will absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Perhaps the biggest element they are missing is the mineralization of ocean carbon, but for the time period they are considering this has little effect:

Importantly, Matthews and Caldeira did not just consider the scenario in which emissions were made as a single pulse (or “slug” as it is sometimes called) and then drops to zero, but as they state, according to:

The results?

This was in agreement with earlier research

Unfortunately, Matthews and Caldiera is paywalled, but:

… obtains similar results and brings in additional aspects, including glaciers, ice sheets, sea level rise, and changes to precipitation.

111 Kevin McKinney, well done with your series of comments!

I recommend http://goo.gl/ for shorter links, as they are ‘persistent’, and they have some other benefits over tinyurl.

113 (and others) Timothy, thank you very much for your contribution here. Well done.

RE: “As such I do not find his (ChrisDs) argument regarding culpability convincing.”

You’re too kind. I find it fraudulent and emotionally driven being not based on the whole of the science nor known related facts.

RE “However, I believe the issue of irreversibility is far more important than that of culpability.”

100% agree. The issue is the “climate” not anything else, and that includes the spurious suggestions that the current form of the global and national economies are more important. My hope is that enough shit will hit the fan regarding both extreme climate responses and a fracturing global economy before the 2015 Paris meeting rocks around so the “myths” can be put aside and the issues dealt with honestly and openly for a change at the UNFCCC etc.

Not holding my breath. But sooner or later the reality will hit home to all. Best.

Timothy (113),

You seem to be imprecise when you mix greenhouse and non-greenhouse forcings there. And the University of Victoria model you relied on earlier is known to be at the high end of lingering warmth. http://www.atmos-chem-phys.net/13/2793/2013/acp-13-2793-2013.pdf

But, even so, it does not keep getting warmer once emissions stop. It stabilizes. If you want more warming you need more emissions. Notice, for example, how the 500 GtC curve immediately departs horizontally from the the 2000 GtC curve in the bottom panel of fig. 2 in Matthews and Calderia. That happens exactly when the emissions cut off, no delayed rise etc… So, all the warming from the 500 GtC is immediately what you get. No inertia etc… If you want more warming, you are going to need more emissions.

To say it again: the science says that if you stop greenhouse gas emissions, the warming stops, so past greenhouse gas emissions are not the reason for future greenhouse warming, future greenhouse gas emissions are.

BTW, there may be an inconsistency in Hare and Meinshausen in the version I looked at, they claim that they set aerosols to zero as well for the constant forcing case, but it seems to have lower forcing than the immediate cessation of emissions case. Just at the point of cessation then, the forcing should be identical if both have aerosols turned off. Interestingly, an emission profiles that gives you constant carbon dioxide it the sort that would probably involve converting coal power to gas power, cutting aerosol emissions. So their intention seems to have foundation, but it is not clear that the execution came off as intended.

flxible (#108),

Regarding the WTO and GATT, intentions are the most important thing. You have to have a domestic environmental law on the books to be able to invoke the environmental exception and apply tariffs to imports from a country that is lacking a law and causing environmental damage. If you are trying to fix the problem yourself, you can use tariffs, if you are not, you can’t. Intent is the deciding factor.

Chris Dudley writes in 103:

I misunderstood you then. My apologies.

You continue:

Omitting aerosols, yes, this is correct. However, if we include aerosols (that due to their cooling effects mask the warming that will result from greenhouse gas emissions once those aerosols are removed) in our analysis, then the final temperature will most certainly be above the current temperature. And over human time scales the warming that results when emissions, including reflective aerosols, are brought to an abrupt end, the rise in temperature that takes place afterwards will be effectively irreversible.

You continue:

Only to the extent that the warming that will be due to past emissions is already included in current temperatures. To the extent that aerosols have masked the warming effect of past emissions such that temperatures initially rise when all emissions (including carbon dioxide and reflective aerosols) abruptly end, the warming that results will be effectively irreversible on the timescale of centuries.

As I stated (113) in response to Diogenes (102), the paper that you directed him to:

… “takes aerosols into account”, showing temperatures rise briefly when emissions are abruptly brought to an end. However, they make your move of simply omitting aerosols from the analysis seem reasonable since according to their analysis the warming due to the cessation of aerosols that appears after emissions are abruptly brought to an end vanishes almost as abruptly as it appears.

However, given a more realistic model, this move of omitting aerosols from the analysis is no longer reasonable. If, as the authors of that paper calculate, the temperature initially rises after the cessation of emissions due to the cessation of the cooling effects of reflective aerosols, then (according to a more realistic model that takes into account the heat capacity of the deep ocean) the warming that takes place at that point will be effectively irreversible:

As I point out, if that warming is dangerous then past emissions are responsible for such dangerous warming.

Now with regard to the issue of culpability which is evidently your paramount consideration, I summarize as follows:

But as I point out in my response to Diogenes, I believe the issue of irreversibility is far more important than culpability. The warming that takes place after the cooling mask of aerosols is removed will be more or less with us for centuries.

Tomothy Chase #113,

When I mentioned the Letter in my post, I was referring to the Matthews and Weaver ‘Committed Climate Warming’ Letter that Hank Roberts referenced in post #8, not the Meinshausen paper. There are really two issues here, and they need to be discussed separately. There is a short-term issue and a long-term issue. We need to overcome the short-term issue so there will be a long-term to address. The short term issue is the temperature pulse due to precipitation of the aerosols if fossil fuel combustion is terminated rapidly. If that pulse is higher than we expect, and given the uncertainties in aerosol forcing it could very well be, it could trigger some of the carbon feedbacks to unacceptable levels, and perhaps put them on autopilot. Geo-engineering that would temporarily replace the aerosols under such conditions might be required.

You are correct about the long-term issue; it needs to be taken into consideration seriously.

DIOGENES (#125),

Because the anthropogenic sulphate aerosols are pretty localized owing to their brief residence time in the atmosphere. So, the warming owing to their elimination will be mainly a local phenomenon. The feedbacks would need to be geographically associated with unsophisticated industrial areas which lack sulfur control. I think we might be mainly worried about increased methane outgassing from warmer rice patties if the wild fire danger is not increased. Permafrost may not be affected at all, being geographically remote.

It it worth noting though that for rice growing regions, the apparent resilience of that crop to warming may have less of a cushion than anticipated since the warming could be stronger than the global average regionally if aerosols are presently locally dense. RCP4.5 may have unaffordable yield impacts for countries where arable land is nearly fully exploited, even to the point where encroachment on bamboo forest habitat for endangered megafauna that are crucially important to a national image has already been an issue.

“Is folly in the filter?” Almost certainly… ;-)

(Especially the Borehole.)

Timothy(#124),

“However, if we include aerosols (that due to their cooling effects mask the warming that will result from greenhouse gas emissions once those aerosols are removed) in our analysis, then the final temperature will most certainly be above the current temperature.”

I wonder if that is really true, or if the front ending of ocean heat uptake in the deeper ocean model might end up compensating somewhat.

There are really two things of interest here: what does the science say about the effect of emissions, and then how does that feed into the liability question that a WTO mediated trade dispute would need to address.

That latter part goes might go like this:

USA to China: China you are not controlling your emissions and we are controlling ours. We are suffering from climate damage from your actions and so we are putting a tariff on your imports to cover our costs. Attribution science has shown that we are paying extra costs in our federal crop insurance and flood insurance programs owing to recent dangerous climate change. Our tariff will cover those extra costs.

China to WTO: Whah Pielke, Whah Christy.

WTO to China: Got to do better than that, the tariff stays.

China to WTO: Whah historic emissions.

WTO to USA: WTF inertia? You can impose a tariff but you have to cover some costs yourself.

USA to WTO: Greenhouse warming is wysiwyg. Here’s why….

WTO to USA: Oh, we’d heard of inertia, but it turns out you are correct. Keep your tariff at its current level.

China to WTO: Whah aerosols: not wysiwig.

WTO to USA: Hey, you fooled us. Lower your tariff.

USA to WTO: We did not fool you, we said “greenhouse warming.”

WTO to USA: Still caused by historic emissions, lower you tariff.

USA to WTO: Not for us. We have an environmental law controlling sulfur emissions that has been on the books for a while. Damage we are suffering is owing to recent greenhouse gas emissions which we are also controlling. Regarding our damages, warming is wysiwig. China may experience a bump from failing to control sulfur emissions and extra damage, but they will have to recover those damages from India not us. We are not liable for historic emissions since we are already controlling current emissions (safe harbor).

WTO to USA: Oh, OK, maybe you have a point, oh wait, China is cutting emissions, end your tariff. We have to hear the India v China case now.

So, the science feeds into this, but the liability issue is more about how GATT is written. You can only sue if you are doing something about the problem yourself, and if you are, you can only sue parties that are not doing something. Sue is not the right word since it would be China, not the US that first approaches the WTO. We’d start by imposing a tariff unilaterally. The compensation starts before the case is decided.

But, that is the idea anyway.

Walter (#121),

Hoping for disaster is not an attitude that is going end up contributing to solutions.

Timothy (#124) asks again: “But were we as developed nations actually so surprised?” regarding the early onset of dangerous climate change.

Yes we were. Politicians like Olympia Snowe had enough scientists tell her that a 2 C rise was the limit at which dangerous climate change started, that she was ready to defy her party and go to bat for action to limit warming to below 2 C. A scientist who has warned about reticence also urged a target of 350 ppm but said that excursions above that could be tolerated if brief enough. Finally he realized empirically that heatwaves, as examples of extremes, have probability distribution tail effects that bring dangerous climate change into our lives much sooner than that scientifically supported 2 C limit. Empirically! Not forecast. The forecast was for 2 C.

So, yes, we were very much surprised by the advent of dangerous climate change. We thought it was still far off.

No, read the opening summary by Stefan again.

You are ignoring the impacts of climate change.

Read the cautions as set out by the IPCC.

That’s the topic here — the damage in the pipeline.

The ocean will keep rising for centuries to come.

Greenland will melt.

Physics doesn’t change based on intent.

Laws change. People change them.

Timothy Chase wrote (#124): “But were we as developed nations actually so surprised? Apparently not …”

Certainly not.

In the Nixon Libary, there is a September 1969 memo from Daniel P. Moynihan to John Ehrlichman which discusses “the carbon dioxide problem” in terms of “apocalyptic change”. Moynihan succinctly describes the problem:

He then goes on to describe some potential impacts:

He then states, “it is possible to conceive fairly mammoth man-made efforts to countervail the C02 rise. (E.g., stop burning fossil fuels.)”

And he concludes by noting that “The Environmental Pollution Panel of the President’s Science Advisory Committee reported at length on the subject in 1965.”

The Watergate investigators addressed the question of culpability thus: what did the president know, and when did he know it?

Clearly, US presidents have been well informed about the “carbon dioxide problem” and the need for “mammoth efforts” to avert “apocalyptic change” for at least 50 years.

Hank (#128),

GATT is a body of law relevant to the course of climate change. Without it, the largest emitter of greenhouse gases would have much less access to foreign markets and would have much lower emissions now. Without it, Sandy might have been avoided. In law, intent often matters. So, it is pretty relevant.

SA (#132),

It is not a question of did people know about the greenhouse effect in 1965. They did not know much about it, and not enough to say that a 2 C warming is the onset of dangerous climate change. So, back is 2006, RealClimate was interested is technical aspects of doing the 2 C limit. https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2006/01/can-2c-warming-be-avoided/ but did not see the limit as an issue. I 2009 it got called “almost cavalier.” https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2009/07/two-degrees/ Tough on the politicians who thought they had a number. There were attribution studies of individual events https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2011/02/going-to-extremes/ and a start at statistical detection of damaging climate change effects as can be seen that 2011 article. But it was the next year where we saw why we should expect problems now rather than at some 2 C limit. J. Hansen, M. Sato, and R. Ruedy, “Perception of climate change”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 109, pp. E2415-E2423, 2012

A lot happened in six years from 2006 to 2012 regarding our understanding that dangerous climate change is now among us (fig. 1 above).

#135–Yes. One landmark not mentioned is “Six Degrees,” which was mentioned by many here at the time.

http://doc-snow.hubpages.com/hub/Mark-Lynass-Six-Degrees-A-Summary-Review

Kevin (#135),

And you can see the heatwave issue is associated with 2 C there, rather than 0.8 C as we now understand it to be. My guess is that the distribution tail phenomenon gives a non-negligible chance of consecutive crop yield wrecking heatwaves in world breadbasket regions that completely deplete our carryover grain stocks at 2 C. A bit of bad luck could lead to unrelivable famine years. Bad luck becomes destiny if we stay for long near 2 C. So, our understanding has certainly evolved since 2008.

134…Talk about not being able to read. From SA @ 132:

“It is now pretty clearly agreed that the C02 content will rise 25% by 2000. This could increase the average temperature near the earth’s surface by 7 degrees Fahrenheit. This in turn could raise the level of the sea by 10 feet. Goodbye New York. Goodbye Washington, for that matter.”

Indeed, who knew? Bet one of your savvy attorneys specializing in liability would have a field day with that document.

Walter (#137),

Look at those numbers. That indicates a climate transient response of 7 C per doubling. Naive speculation is occurring there.

CD, that said 7F, not C; that was not a bad guesstimate in 1969 compared to current climate sensitivity estimates, and the lag time for sea level to rise was understood — the damage was understood to be in the pipeline.

Chris Dudley wrote in 104

I may be somewhat out of the loop with regard to the politics, but from what I have seen, typically developing countries argue that the developed world owes much its development to its use of fossil fuels and it would be unfair to expect developing countries to match the cuts in fossil fuel use that the developed world should make when this would result in developing countries remaining poor. As such it isn’t tied to the sort of “climate inertia” argument you are arguing against. Another related argument is that even now developed countries are responsible for considerably more emissions than developing countries on a per capita basis. In 2010 the average US citizen produced 17.6 tons of CO2 but the average Chinese citizen produced 6.2. No doubt this has changed in the past four years, but I strongly doubt it has reached parity. These are I believe the two most common arguments. Neither relies on a “geophysical commitment” to future warming once emissions have ceased.

Chris Dudley continued:

Informal logic does not support arguing issues of physics based on their political implications. You seem to be quick to dismiss the results of more recent papers based on relatively advanced climate models in favor of an older paper which, by the admission of its own authors is based on a “simple model.”

Regardless, I don’t think the question of responsibility on a national or per capita basis should be regarded as the central issue. We should be primarily concerned with reducing future emissions, preferably without reducing living standards or opportunity. And there are several major steps we could take in this direction.

One of course is a carbon tax, perhaps the least controversial of which would be revenue neutral, entirely offset by reductions to other taxes according to an “across the board” (ATB) approach. Others might argue for keeping the revenue for the purpose of subsidizing the development of renewable energy or else a revenue neutral “fee-and-dividend” model (FAD) where revenue is given back to citizens on a per capita basis. While I might sympathize with the intents behind the other approaches I would prefer not to see the other issues linked in this fashion. In particular, the latter might strike some as a form of social engineering. And as long as one is taking an ATB approach it is likely that a fairly high carbon tax could be implimented on a state-by-state basis without putting those states (or for that matter, those countries) that impliment it first at a disadvantage.

For more on this, please see:

… and the economic study linked to in the first paragraph of the article. A carbon tax could later be married to tariffs on those governments that have not implemented their own domestic carbon taxes until such time as they implement such a tax. However, even without tariffs it would move the developing world forward to the extent that domestic innovation and economy of scale make renewable energy more affordable internationally.

A second step would be various forms of legislation that support distributed renewable energy, much of which has interestingly enough found support among Libertarian and Tea Party groups.

Please see for example:

A third step would be to eliminate subsidies to fossil fuel.

These are quite substantial on both a global basis and at considerable cost:

Those interested in persuing this issue in the United States may wish to see:

Incidentally, the recommendations I have given above should be acceptable to most conservative groups except to the extent that those organizations place vested fossil fuel interests ahead of those of their rank and file, but this does not mean that I am opposed to other approaches.

Hank (@139),

Do the math. 1965 Keeling Curve: 318 ppm. 25% more: 397 ppm (actual value about 366 ppm so over estimated which is fine). Ratio to preindustrial: 1.41. ln(1.41)/ln(2)=0.5 so half the temperature effect of a doubling. Doubling implies 14 F transient response so 7.7 C transient response in more familiar units. A fast feedback sensitivity of 11 C per doubling or higher might correspond to that. This was a naive first pass at looking at the issue, not solid knowledge that a conspiracy has been hiding ever since.

PS My tons per capita for China and the United States comes from:

I do not know, however, whether this is calculated by attributing the carbon dioxide to the source (producer) or destination (consumer). The latter would seem to be the correct approach — and would take care of the problem of reducing domestic emissions by outsourcing carbon-intensive production.

#136–Yes. Lynas in fact devotes large amounts of space in the book to the 2003 heatwave. It’s primarily associated with the 2 degree world because that’s roughly the amount by which the norm was exceeded during that disaster. (Note, BTW, that ‘we are living in the 1-degree world’ now, according to Lynas’ scheme of things–and in fact, the 2003 heatwave is the subject of a section in the 1-degree world, Danger in the Alps.)

http://doc-snow.hubpages.com/hub/The-One-Degree-World

http://doc-snow.hubpages.com/hub/The-Two-Degree-World

No argument that understanding has evolved.

CD@141…Better put that attorney on retainer. In 1979, JASON produced its report, The Long Term Impact of Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide on Climate. Hardly naive, and the highest level of the U.S. government had the information to make informed decisions.

Knowing the cumulative impacts, only a dedicated Chinaphobe would fail to assign culpability to the one nation that had the facts for decades yet until recently was the single largest CO2 emitter.

> do the math

No, read the quote, from 1969:

“C02 content will rise 25% by 2000. This could increase the average temperature near the earth’s surface by 7 degrees Fahrenheit.”

What’s between the quotation marks is what they wrote: “will rise” by a specific time, and “could increase” — as a consequence.

Not a bad guesstimate — understanding that the consequences are not immediate. As we do.

Timothy (#140),

You might be please by this news. http://news.ninemsn.com.au/world/2014/04/12/08/01/imf-world-bank-push-for-price-on-carbon “The IMF and World Bank have urged finance ministers to impose a price on carbon, warning that time is running out for the planet to avoid worst-case climate change.”

Tariffs on Chinese imports would essentially be a price on carbon. I think though for internal emissions, we’ll use regulation since that is how we handle pollution. There is a cap-and-trade program in sulfur emissions, which has been considered innovative and which has been applied to greenhouse gas emissions in Europe. But with regulations coming that will close nearly all coal plants, the sulfur issue may be left well under the cap.

Walter (#144),

I just wonder how the Jasons got so far out ahead of people like Gavin that he is only just catching up now. We could have just skipped FAR, SAR, TAR, FAR, AR5 and gone right on to AR6. What a waste of effort all that has been.

Walter (#144),

I’m rather fond of the government in Taiwan which, with out lengthy negotiations, and always under heavy military threat, is cutting emissions now and has a plan for cuts out to 2050. http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/03/16/idUSTOE62F04M

You may be unaware the the atrocious human rights record of the government on the Mainland. They massacre peaceful student protesters there, not like Kent State, but with rolling tanks. I sat stunned and saddened with friends and family in Taipei as this atrocity unfolded. Perhaps you should not assume quite so much when you call people names.

140, Dear Tim re “Another related argument is that even now developed countries are responsible for considerably more emissions than developing countries on a per capita basis.”

More than that “per capita basis” Tim, the total quantity in GtC emissions is still clearly very much higher now (2013/14) for all developed nations versus developing countries, even if you include China in the latter. See various figures from IEA, EIA, Hansen et al, my refs in comments here recently, IMF, OECD, ad nauseum. Plus Non-Hydro renewable energy capacity is still floating somewhere between 1 and 2 % globally. Sorry no time to repeat sources.

Currently this BAU status is physically, scientifically impossible for said renewables, plus Hydro, plus planned Nuclear expansion more than doubling, to meet the reduction of Carbon energy supply to be below ~78% of total global energy use by 2040. 2012 carbon energy was 83% of the total. Found your website long ago, good to see you here sharing your astute knowledge and experience, Best.

142 Tim, ” whether this is calculated by attributing the carbon dioxide to the source (producer) ” it is always attributed to the producer of said CO2e emissions when it is “burnt and emitted”.

Not the consumer, and not the mining source nation either — except for fugitive emissions of CO2/CH4 etc from coal mines and Gas exploitation at the source etc. and the mechanisation that is fossil fueled, ie trucks diggers transportation to the Ports for export etc.