A new study by British and Canadian researchers shows that the global temperature rise of the past 15 years has been greatly underestimated. The reason is the data gaps in the weather station network, especially in the Arctic. If you fill these data gaps using satellite measurements, the warming trend is more than doubled in the widely used HadCRUT4 data, and the much-discussed “warming pause” has virtually disappeared.

Obtaining the globally averaged temperature from weather station data has a well-known problem: there are some gaps in the data, especially in the polar regions and in parts of Africa. As long as the regions not covered warm up like the rest of the world, that does not change the global temperature curve.

But errors in global temperature trends arise if these areas evolve differently from the global mean. That’s been the case over the last 15 years in the Arctic, which has warmed exceptionally fast, as shown by satellite and reanalysis data and by the massive sea ice loss there. This problem was analysed for the first time by Rasmus in 2008 at RealClimate, and it was later confirmed by other authors in the scientific literature.

The “Arctic hole” is the main reason for the difference between the NASA GISS data and the other two data sets of near-surface temperature, HadCRUT and NOAA. I have always preferred the GISS data because NASA fills the data gaps by interpolation from the edges, which is certainly better than not filling them at all.

A new gap filler

Now Kevin Cowtan (University of York) and Robert Way (University of Ottawa) have developed a new method to fill the data gaps using satellite data.

It sounds obvious and simple, but it’s not. Firstly, the satellites cannot measure the near-surface temperatures but only those overhead at a certain altitude range in the troposphere. And secondly, there are a few question marks about the long-term stability of these measurements (temporal drift).

Cowtan and Way circumvent both problems by using an established geostatistical interpolation method called kriging – but they do not apply it to the temperature data itself (which would be similar to what GISS does), but to the difference between satellite and ground data. So they produce a hybrid temperature field. This consists of the surface data where they exist. But in the data gaps, it consists of satellite data that have been converted to near-surface temperatures, where the difference between the two is determined by a kriging interpolation from the edges. As this is redone for each new month, a possible drift of the satellite data is no longer an issue.

Prerequisite for success is, of course, that this difference is sufficiently smooth, i.e. has no strong small-scale structure. This can be tested on artificially generated data gaps, in places where one knows the actual surface temperature values but holds them back in the calculation. Cowtan and Way perform extensive validation tests, which demonstrate that their hybrid method provides significantly better results than a normal interpolation on the surface data as done by GISS.

The surprising result

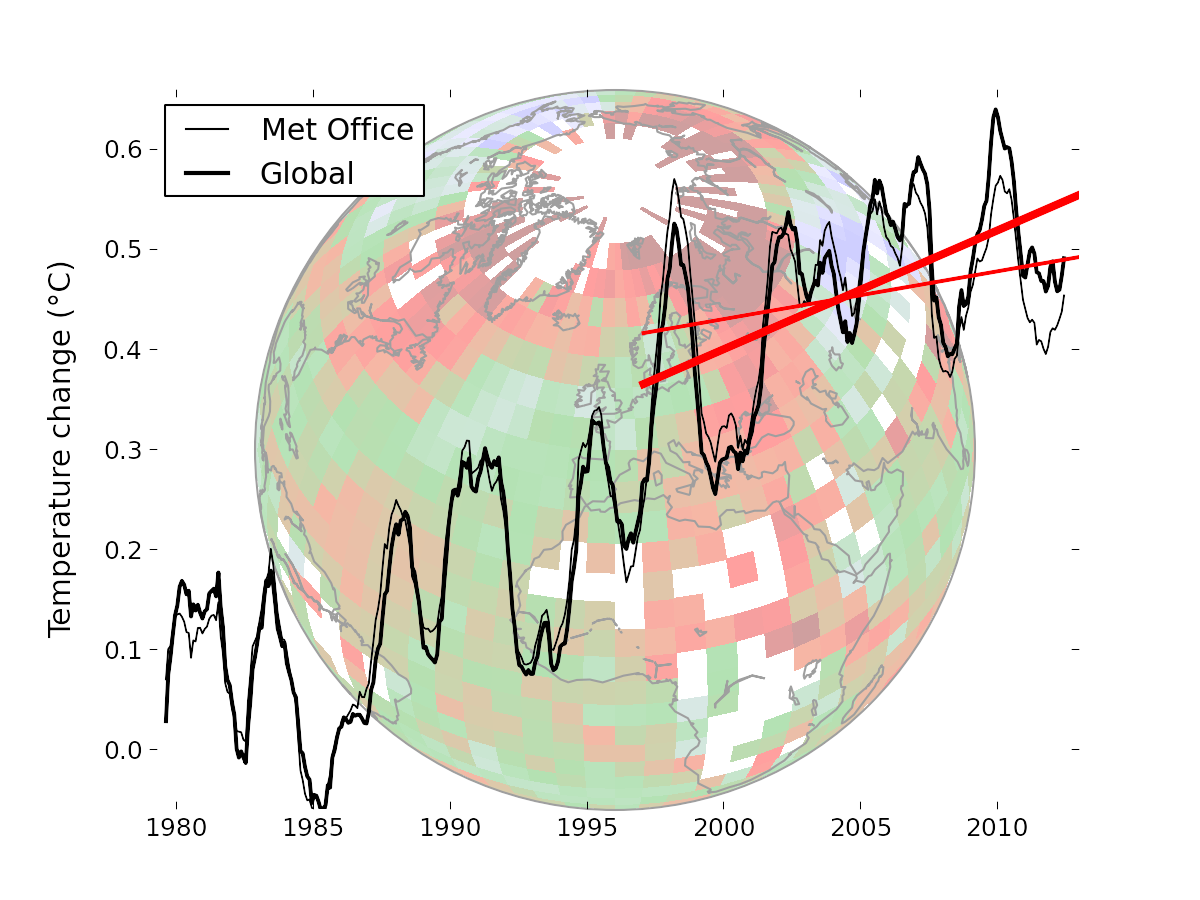

Cowtan and Way apply their method to the HadCRUT4 data, which are state-of-the-art except for their treatment of data gaps. For 1997-2012 these data show a relatively small warming trend of only 0.05 °C per decade – which has often been misleadingly called a “warming pause”. The new IPCC report writes:

Due to natural variability, trends based on short records are very sensitive to the beginning and end dates and do not in general reflect long-term climate trends. As one example, the rate of warming over the past 15 years (1998–2012; 0.05 [–0.05 to +0.15] °C per decade), which begins with a strong El Niño, is smaller than the rate calculated since 1951 (1951–2012; 0.12 [0.08 to 0.14] °C per decade).

But after filling the data gaps this trend is 0.12 °C per decade and thus exactly equal to the long-term trend mentioned by the IPCC.

The corrected data (bold lines) are shown in the graph compared to the uncorrected ones (thin lines). The temperatures of the last three years have become a little warmer, the year 1998 a little cooler.

The trend of 0.12 °C is at first surprising, because one would have perhaps expected that the trend after gap filling has a value close to the GISS data, i.e. 0.08 °C per decade. Cowtan and Way also investigated that difference. It is due to the fact that NASA has not yet implemented an improvement of sea surface temperature data which was introduced last year in the HadCRUT data (that was the transition from the HadSST2 the HadSST3 data – the details can be found e.g. here and here). The authors explain this in more detail in their extensive background material. Applying the correction of ocean temperatures to the NASA data, their trend becomes 0.10 °C per decade, very close to the new optimal reconstruction.

Conclusion

The authors write in their introduction:

While short term trends are generally treated with a suitable level of caution by specialists in the field, they feature significantly in the public discourse on climate change.

This is all too true. A media analysis has shown that at least in the U.S., about half of all reports about the new IPCC report mention the issue of a “warming pause”, even though it plays a very minor role in the conclusions of the IPCC. Often the tenor was that the alleged “pause” raises some doubts about global warming and the warnings of the IPCC. We knew about the study of Cowtan & Way for a long time, and in the face of such media reporting it is sometimes not easy for researchers to keep such information to themselves. But I respect the attitude of the authors to only go public with their results once they’ve been published in the scientific literature. This is a good principle that I have followed with my own work as well.

The public debate about the alleged “warming pause” was misguided from the outset, because far too much was read into a cherry-picked short-term trend. Now this debate has become completely baseless, because the trend of the last 15 or 16 years is nothing unusual – even despite the record El Niño year at the beginning of the period. It is still a quarter less than the warming trend since 1980, which is 0.16 °C per decade. But that’s not surprising when one starts with an extreme El Niño and ends with persistent La Niña conditions, and is also running through a particularly deep and prolonged solar minimum in the second half. As we often said, all this is within the usual variability around the long-term global warming trend and no cause for excited over-interpretation.

Look again at the RC topic from 2004, where this was pretty thoroughly gone over. Link and quote about the AMO involvement there posted just above at 5 Dec 2013 at 4:12 PM — the bit quoted begins

Nobody’s ignoring that. It’s history.

Look at in recent papers, e.g. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924796313002236?np=y

Do you see something new others haven’t published or discussed here since 2004, and earlier? This has really been gone into over and over.

MARodger,

> Bar a 25 year period 1940-65, the Arctic temperatures are rising over the entire record. Is this your basis for arguing for a hypothetical 70-year Arctic cycle?

Also add some indirect evidence for previous cycles. But I’m glad you recognise the warming, bar the middle period. I trust that no one here will claim that all the warming since 1880 in that graph is due to AGW with an offset that built up from 1940-1970 and stayed due to soot, volcanos, etc.

Et al.,

If it helps, I’ll happily make some semantic adaptations. To describe the observations in the Arctic I’ve spoken of a possible cycle (or quasi-cycle since the periodicity and amplitude might vary somewhat as I’ve argued) of about 70 years. I can just as well use the term Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillion instead and speak of its local effects in the Arctic, and if it’s bad to hint that AMO could sometimes have a larger swing up every 70 years roughly, I can refrain from that for now. I do not think there exists an independent Arctic cycle. Everything is of course interconnected, and the Arctic is directly influenced by the Atlanic.

So, if we can agree that AMO is exists with or without AGW and that it influences the Arctic, possibly causing greater variability there than elsewhere, I can rephrase the original question: what if the recent Arctic warming has been amplified by AMO, isn’t that weakening the “no AGW hiatus” argument, assuming that AMO is not a consequence of AGW?

Steinar Midtskogen @253.

I fear you will have you work cut out trying to present any AMO causation for substantial parts of Arctic warming since 1880 because, unlike the Artic temperature record (as per GISS), the AMO index since 1880 has shown far more than a single period of non-warming.

And be warned that the AMO is well-trampled ground. There are quite a few who have tried to suggest that the AMO is the cause of the ‘hiatus’ as it must surely be in the process of dipping by now, it being an oscillation and all and that is what oscillations do when their time is due. Or in fact overdue. As of October 2013, the AMO stubbornly refuses to cooperate.

Steinar,

We have no problem calling the solar cycle a cycle, despite its deviations from strict periodicity, because we understand the physical processes underlying it. One cannot say the same of your putative 70-year cycle. And since we do not know the underlying physics, we cannot say if it is independent of the warming trend or whether it exists at all. Again, you are getting very excited by very weak evidence.

MARodger,

> “I fear you will have you work cut out trying to present any AMO causation for substantial parts of Arctic warming since 1880 because, unlike the Artic temperature record (as per GISS), the AMO index since 1880 has shown far more than a single period of non-warming.”

Since it’s apparently not kosher to speak of cycles with variable amplitude, possibly variable period, for which direct measurements aren’t yet long enough to do proper statistical analysis, unless it has an 3 or 4 letter abbreviation, I’m stuck with the AMO. AMO is not Arctic surface temperature, and correlation is not causation, but it takes some effort to disregard the signs of correlation. Again, I remind you that AMO surely isn’t the only thing controlling Arctic temperature, but if you assume an AMO correlation and add a global warming trend, we seem to get a bit closer.

What is your time window for saying “far more than a single period of non-warming”? As I’ve clearly stated, I’ve been using the standard climatic 30y average. If you do that on the AMO data that you provided, you get the same apparent ~70 year periodicity that I’ve been suggesting, but to avoid further discussions on the periodicity and whether the 30y AMO and corresponding Arctic temperatures in the 2030’s will show a turn around now, the main point is the turn at the beginning of the satellite measurements, precisely as in the Arctic temperature record. That coincidence could be a problem for the study unless it deals with it somehow (by denying an AMO-Arctic temperature link, for instance).

Steinar Midtskogen @256.

When I say “far more than a single period of non-warming” you capture the issue well with the graph of AMO you link to @256. The GISS Arctic temperature record (graphed red here) shows but one period of falling temperature 1940s-1960s. (You might also squeeze a second tiny one in around 1910.) Otherwise, the only way is up! Yet the Enfield AMO record in your graph presents a big meaty oscillation peaking in the 1870s & the 1940s. How then can the AMO present itself as a significant feature of Arctic temperature? Where are you “signs of correlation” that you say “takes some effort to disregard”? I am finding it an effort to see them.

I would add that you should not be reluctant to consider cycles/oscillations. If there is data to demonstrate a wobble, there is a wobble. The AMO appeared within the analysis that gave us the hockey stick graph. Since then a lot of work has shown evidence of some sort of AMO wobble back through time although it doesn’t exhibit itself in the ways you would consider obvious, like say a massive signal on say the Central England Temperature record. Likewise, it appears, the Arctic.

MARodger,

> “The GISS Arctic temperature record (graphed red here) shows but one period of falling temperature 1940s-1960s.”

We can only expect one period of falling temperatures in the instrumental temperature record of the Arctic simply because we don’t have sufficient instrumental data going back to the 1850’s. Data becomes scarce going back more than 100 years, and your GISS graph shows a 10y average. If you had used the standard 30y average, your plot would only go back to 1895 and you would simply see a bottom between 1895 and 1906, and even that period would be somewhat uncertain, so I would hesitate to call it inconsistent with the AMO bottom in the early 1910’s. We can’t pinpoint a certain year within a decade for bottoms and peaks anyway, which heavily depend on the kind of smoothing used. Moving averages certainly shift that if the edges are not symmetrical, which we cannot expect if the periodicity and amplitudes are indeed somewhat variable.

> “Where are you “signs of correlation” that you say “takes some effort to disregard”? I am finding it an effort to see them.”

So if we don’t have good instrumental evidence for a warm period from around 1850 to 1870, nor the direct evidence for the contrary, can we then be sure of an AMO and Arctic temperature link? No, but I believe there is enough to keep an eye or two open for that possibility. We have one period of warming, which was before any large scale emission of CO2, we had one cooling period, and the another warming period, all very well timed with the AMO turns. In a couple of decades we’ll know if this holds a fourth time in a row.

But let’s return to the study again. It picks 1979 as it’s starting year. Then look at the AMO graph above. And some Arctic temperature records (from GISS, picking a few going long back):

Nuuk, Reykjavík, Ostrov Dikson

Let’s disregard all discussions on AMO-Arctic temperature links, causes and periodicity. Can we just agree that something happened in those 30y trends ca. 1979? Is it really no concern whatsoever to introduce an inhomogeneity for Arctic temperature at that point by shifting to satellite measurements from 1979?

Errr…Steinar, last time I checked GISTEMP (which is also shown in MARodger’s graph) doesn’t use satellites. So, considering the land-based measurements follow the same trend as the satellite record, perhaps the concern that there may be an inhomogeneity for Arctic temperature by shifting to satellite measurements is, like, unnecessary?

Steinar Midtskogen @258.

I find little of merit in what you present here.

If a 30-year rolling average were used on the GISS Arctic temperatures you would not see a “a bottom between 1895 and 1906.” You would see it rising steeply from the off. The only way is up!!

I cannot countenance any of the objections you raise which allow you to “hesitate to call it inconsistent with the AMO bottom in the early 1910′s.” A significant AMO signature is absent, pure and simple, from the GISS Arctic temperature record.

Thus things cannot very be auspicious for your reply to my second quote from ‘@257’.

Indeed, I insist that you are dismissing “direct evidence for the contrary.” The inflections in the temperature records in the 1940s and 1970s are present globally and in many places regionally. Many see a prior inflection in the records in the 1910s as having the same status although this 1910s version is absent in the Arctic record. (The three inflections are enough to prompt some to speculate forcefully that AMO runs through the whole world. Note this; many apparently find this an attractive prospect but their analyses are flawed nonetheless.)

Particular to the Arctic, these two Arctic inflections are certainly not enough reason to wait in anticipation for “a couple of decades” for a 4th inflection. It is not even enough to wait in anticipation a couple of years for the 3rd!

The study (I assume you refer to Cowtan & Way 2013) cannot extend back prior to the satellite era for obvious reasons. To suggest that their start-date was “picked” is disingenuous. And of course any study using satellite data will suffer “inhomogeneity” at 1979. Beyond regret that them there satellites weren’t launched earlier, I am not sure where any “concern” would lead. A grassy knoll? Rosewell Area 51? I am not inclined to be lead in such directions!

Marco,

You misunderstand. I do not claim there is an inhomogeneity in GISS. Rather, that an inhomogeneity arises if you talk about 20th century GW and use satellites for the Arctic since 1979, and that it could make a difference because of the turn in AMO around 1979.

Haven’t been following this in detail, but that graph sure looks like a trend plus variability (which COULD, but need not be, in the form of one cycle of an oscillation) to me.

The graph gives annual, as well as smoothed, values. I think that a 30-year smooth would not change the picture, except to the extent that it would ‘smooth over’ information. And “+1” for Marco’s comment.

MARodger,

Their “pick” of 1979 marks of course the start of available satellite data. Purely coincidental, that time also marks the turn of the AMO when looked through 30y glasses. And the turn of Arctic temperatures also seen through 30y glasses. One can think there is an AMO or Arctic temperature link, or one might find an ad hoc explanation for every correlation. In the latter case 1979 might not matter much, but if you do not rule out such a connection, some care must be taken. The study could then also argue that the global cooling from 1940 to 1980 has been underestimated.