There are two interesting pieces of news on the global temperature evolution.

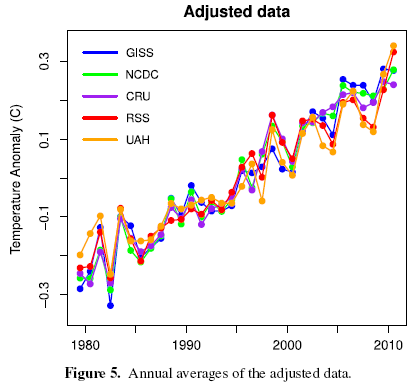

First, today a paper by Grant Foster and Stefan Rahmstorf was published by Environmental Research Letters, providing a new analysis of the five available global (land+ocean) temperature time series. Foster and Rahmstorf tease out and remove the short-term variability due to ENSO, solar cycles and volcanic eruptions and find that after this adjustment all five time series match much more closely than before (see graph). That’s because the variability differs between the series, for example El Niño events show up about twice as strongly in the satellite data as compared to the surface temperatures. In all five adjusted series, 2009 and 2010 are the two warmest years on record. For details have a look over at Tamino’s Open Mind.

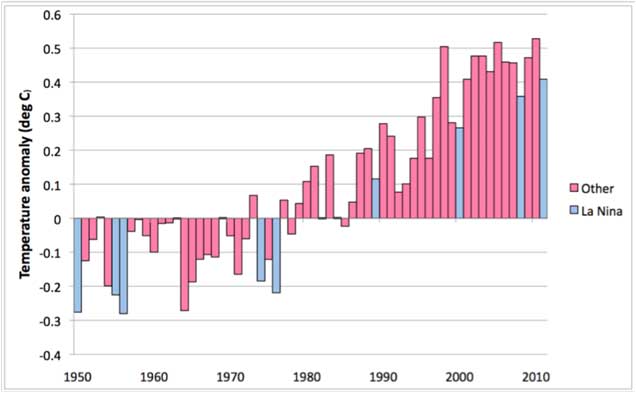

Meanwhile, the World Meteorological Organisation has recently come out with a Provisional Statement on the Status of the Global Climate for 2011. In addition to a discussion of some of the extreme events of 2011 this also comes with a first estimate of the 2011 global temperature, see their graph below:

They find – pretty much in line with the Foster and Rahmstorf analysis – that La Niña conditions have made 2011 a relatively cool year – relatively, because they predict it will still rank amongst the 10 hottest years on record. They further predict it will be the warmest La Niña year on record (those are the blue years in the bar graph above).

References

- G. Foster, and S. Rahmstorf, "Global temperature evolution 1979–2010", Environmental Research Letters, vol. 6, pp. 044022, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/044022

Richard C,

I don’t think the study says anything about long-term cycles. The reference period is only ~30 years so any longer term effects will simply be part of the apparent trend.

There was a large volcanic episode in early-1982 followed by an extreme El Nino in 1983 (comparable to 1998). I imagine these large overlapping competing factors, at that point and elsewhere, played havoc with calibration of the model which leaves the adjustments being useful but less than perfect.

RichardC,

Depends on what you mean by “long-term” here. Have you heard of Milankovitch Cycles?

@10 – No global LIA? Surely you jest?

climate.envsci.rutgers.edu/pdf/FreeRobock1999JD900233.pdf

RichardC asks:”What’s interesting to me is the linearity of the results using just solar variability, ENSO, and volcanoes. Does this study suggest that there are no long-term cycles of any significance?”

Pretty much, for a 30 year period. There may be some cycles on decades or century timescales, but with low amplitude (i.e. significant impact). Longer term cycles would be too slowly changing over 30 years.

I also wonder what happened in 1981-2-3. What caused the gyration in all the data sets?”

Mt. Pinatubo.

You’re pointing out that analyses of different things show different things? OK, then. That wouldn’t seem to justify your insinuation that there’s something untoward about the Foster and Rahmstorf analysis. It’s almost as if you don’t have anything of substance to say.

PKT, short time spans don’t allow detection of a trend.

You don’t like the picture.

That doesn’t mean the authors are trying to fool you with it.

You don’t like seeing the pointy bit on the right higher than the flattish bits on the left. OK, we get that.

You think the whole line looks too steep.

You found a less steep one in Zeke’s article — OK, we get it.

But you’re fooling yourself focusing on the appearance of the picture while ignoring the data behind the chart.

You can’t understand climate just looking at pictures of charts.

Yes, people can be fooled by them. We know that. But — you can’t force all the charts to use the same scale or time span. They’re _pictures_ of data.

Take any climate science question. Test it for yourself.

Put it into Google, then into Scholar, then into Google Images.

Google gets you a dog’s breakfast of information.

Scholar gets you mostly science, with a smattering of, er, other stuff.

Image search gets you — invariably — mostly denial/PR blogs.

Why?

The pictures impress people who don’t understand the arithmetic.

OK. That’s your point, we get that. But you can’t fix the _pictures_.

People who point to pictures _without_ explaining them can’t be trusted.

Don’t assume you know the motivations of the authors.

Read the text. Read the captions.

You’re arguing against a picture because you don’t like the picture.

Instead, try to understand it.

I’m writing today as less of a comment and more of a call for help. I have a very strong science background (mostly in the biological sciences) but I have to admit I’m very much lacking knowledge in climate science. So much so that I don’t even feel comfortable commenting on it.

I’ll turn myself over to you experts. Can you all recommend any good sites where I can learn the truth from the ground up? I have a science based website and I’m sure the topic will come up some day.

Thanks in advance for your assistance.

–Guy McCardle

The Inconvenient Truth

As I said at Tamino’s blog, I have done a very similar analysis (but far less sophisticated) to that in Foster/Rahmstorf using nothing but Excel and manually tuning the magnitude and lag of the ENSO, AOD, and solar forcings. It’s quite easy to do, and while it isn’t worthy of publication by any means, anyone with Excel and a small amount of statistical knowledge can verify Foster & Rahmstorf’s basic conclusions for themselves.

In fact, the more I think about it, the more I think that doing the basic analysis is so easy that it ought to be required of anyone who wants to be taken seriously in a discussion of climate in which math, data, and science are involved. I don’t know how anyone could comes away from their own analysis still thinking “it’s all natural variability” or anything similar. And these days, nearly everyone’s got Excel or something similar.

LIA was mostly a European and possibly a northen hemisphere cooling. The notion of sychronous global cooling during LIA has been dismissed ( Bradley & Jones 1993, Jones at al. 1998, Mann 1999 etc. etc.)

PKthinks, to paraphrase Crocodile Dundee: *that’s* not scaling axes, *this* is:

Denial Depot takes on arctic sea ice extent

(too bad that site’s gone a bit stale. The post complaining about the thickness of pencils used to draw graphs was priceless)

Guy McCardle @57 — There is the start here at the top of the page. That will, in part, direct you to “The Discovery of Global Warming” by Spencer Weart which is also linked (first) in the science section of the sidebar.

@ Guy McCardle

In addition to the sage advice from David B. Benson above, I also suggest that interested people go to Skeptical Science for over 4,700 different threads discussing the various nuts&bolts (and controversies) of climate science. There is an immense amount of reference material discussed there and it can be a bit difficult at first to find an answer to your questions. That’s why it’s recommended to peruse the Newcomers, Start Here thread first followed by The Big Picture thread.

I also recommend watching this video on why CO2 is the biggest climate control knob in Earth’s history.

Further general questions can usually be be answered by first using the Search function in the upper left of every Skeptical Science page to see if there is already a post on it (odds are, there is). If you still have questions, use the Search function located in the upper left of every page here at Skeptical Science and post your question on the most pertinent thread.

Remember to frame your questions in compliance with the Comments Policy and lastly, to use the Preview function below the comment box to ensure that any html tags you’re using work properly.

Guy (#57)

Depends on what you want to learn. If you’re looking for general assessments of climate change, the IPCC 2007 report is probably the most comprehensive single source, and while there’s been good progress since then on a number of topics, not thehing in “big picture” has really changed. The National Academies also has several online reports on the subject, as does USCCP, depending on your interests (the recent 2010 Climate Stabilization report is a great read).

For a more general climate physics background, textbooks are probably the only good route. “Global Warming: The Complete Briefing” by Houghton, as well as David Archer’s “Understanding the Forecast” are great as a qualitative (or some algebra at the most) based introduction that covers many of the big topics needed to start discussing the issue. These might actually be something good to read before the IPCC report.

For more climate physics, Dennis Hartmann’s is good, less based on climate change than climate dynamics in general, and a bit more mathematically rigorous. Ray Pierrehumbert’s is one of the more thorough, although might have a lot of information you’re not interested in, and while it gives you all the tools to think about climate change, is not a “climate change” book per se.

First paragraph– “…nothing in the “big picture” has really changed”

Guy McCardle @ 57, by all means start with Spencer Weart as recommended. You can order the book right now. It doesn’t cost much. I think all the contents are also online but it is best to read an actual book offline for some longer things (not too long in this case).

While waiting for the book to arrive you can start learning about Fourier, de Saussure and others:

http://hubpages.com/hub/The-Science-Of-Global-Warming-In-The-Age-Of-Napoleon

http://hubpages.com/hub/Global-Warming-Science-In-The-Age-Of-Queen-Victoria

http://media.wiley.com/product_data/excerpt/73/14051961/1405196173-38.pdf

http://geosci.uchicago.edu/~rtp1/papers/NatureFourier.pdf

…

By and by plan on learning the Stefan-Boltzman law (with a consequence often referred to as the Planck feedback) and the “bare rock approximation.”

On grasping that our environment is much warmer than the bare rock approximation you will not be mystified that global warming occurs….

After a planet’s basic heat balance, planetary physics is also about all the consequences of the constant energy flux through the environment. Then there is paleoclimatology and more.

#60 SM very good, I still think F+R win that prize

#65–

Thanks for linking those, Pete.

Also, and a tad less familiarly–a (fairly) quick historical survey of the observational study of radiation in and above the atmosphere–or at least a few of its high points:

http://doc-snow.hubpages.com/hub/Fire-From-Heaven-Climate-Science-And-The-Element-Of-Life-Part-One-Fire-By-Day

http://doc-snow.hubpages.com/hub/Fire-From-Heaven-Climate-Science-And-The-Element-Of-Life-Part-Two-The-Cloud-By-Night

Perhaps you could articulate a coherent reason for thinking that.

Guy McCardle, if you are still “here”, I’m going to partly disagree with Chris Colose. This would generally be considered absurd since he is way ahead of me in climatology, but of course you will know what works for you.

If you start with Skeptical Science (which is greatly appreciated by the reality oriented community) what you find is one argument after another after another with no end in sight. On the other hand if you start with fundamental science then the argument over the big picture ended some time in the past. Chris probably agrees and was too modest to mention this.

Skeptical Science example: in one of their recent posts they counter someone who has a convoluted argument that sea level is not rising. Well, is it or isn’t it?

First, as a known physical fact it is.

Second, there are basic physical reasons like conservation of matter that make it rise.

1) thermal expansion of the oceans: measured ocean heat content keeps increasing and this causes the ocean to expand.

2) loss of land based ice: both land based observations (Glacier National Park for instance) and satellite gravity measurements make it clear that land based ice is decreasing.

So where is the water? Is it in the air? In a warmer world there is more evaporation (and precipitation) and more water is in the air. I have seen this estimated as about the volume of Lake Superior so far. This is no match for 1 and 2 above. Is it in the earth? In fact when there is a year of heavy flooding, drainage can’t keep up and sea level drops, but this variation is superimposed on the long term trend of rising seas. Over long time periods the amount of water within the earth’s crust can vary, but we are depleting aquifers (partly countered by building reservoirs). So by conservation of water, sea level must be rising. Of course scientists check and check and compare measurements against each other. But they don’t really suspect water is vanishing from the planet and neither should you.

In short: I suggest getting a handle on the physical basics, and linking people to sites like Skeptical Science if they insist on arguing. At least initially, and permanently for most people, all the details at Skeptical Science (eg of individual arguments against physical realities) are a distraction. It is nevertheless very valuable to have a site like Skeptical Science on hand.

Looking at the bottom graph, or perhaps in general. Shouldn’t one say “in a time-scale DOMINATED by non-La Nina episodes, La Nina seems to not be very influential”? Although I like how you frame this otherwise from your point of view, I think the above statement would be more correct, no?

Guy @ 57 (climatology resources)

I’ll weigh in on this a bit. You asked specifically for “sites” – I presuming that you want something you can read on the web. I strongly suggest that you consider other sources, particularly in the form of textbooks for undergraduate (or perhaps graduate) university courses. What university or college libraries are close at hand? Or a university bookstore? Nearly any introductory physical geography text will have a decent section on descriptive climatology, and this will be a starting point for the basics. (The only exception I can think of offhand would be the one that has Tim Ball as a co-author.) If you can’t sign the books out, one of these would probably make an easy afternoon’s quick read in the library, based on your description of your science background. Don’t expect there to be much math – but that will make it easy to get your head around the basic concepts.

Next step would be to peruse the library stacks for more advanced undergraduate texts. I used to use Henderson-Sellers and Robinson’s “Contemporary Climatology” – back when it was in a first edition. I see it’s now in a second edition, but even that is only from 1999. Expect some more math and detail, but still a fairly easy read. Not an afternoon, but a couple of weekends might do. There are probably lots of similar books (a search for “climatology” at Amazon yields over 8,000 books), and going with what is available locally is simplest. Again, if you don’t have borrowing rights at the local U, try an interlibrary loan through a municipal library. Or, if they have a decent book in the local university bookstore, you may want to buy yourself a copy. Now may be a good time if they are bringing in texts for the second term. [Side note: they still do use textbooks at universities, don’t they??? Jeez, I feel old…]

When I was an undergrad, we used Sellers “Physical Climatology”. That’s clearly dated now (printed in the 1960s), but is a classic. Covers earth-sun relationships, radiation and energy balances, microclimatology, and includes some math. Shows up for $7.98 (used) on Amazon. I’ve also heard that Hidore’s book is not too bad, but I have no direct experience with it. It’s the first hit in Amazon’s “climatology” search.

Once you get going with some basics, you can focus in on which part of the subject you want to learn more about. At that point, come back here with a description of what you have learned and what you want to learn, and get more suggestions. If you start with something too specific or advanced, you’ll find that sources may assume more than you already know.

…and as things progress, come back and post and tell us what you’ve done and how things are going…

A plea:

The picture at the top — used to illustrate the original post — is a composite, without spaces between the pieces, and if you just look at the picture without finding the description, you’ll boggle when you read the numbers along the Y axis.

It’s a composite of four different charts — with overlapping temperature span — but the four are stacked so it looks like one big X/Y chart.

I know, “don’t do that” — but a lot of visitors you might think of as ‘readers’ are in practice ‘viewers’ — so better pictures would better serve those who come here to look and go away after looking.)

All the originals are available where that comes from.

Any chance someone with a connection to the work could do a graphic illustration that works for this?

Pick pictures and write simple captions to explain what’s being published?

http://www.pmodwrc.ch/tsi/composite/pics/

Thanks so much to everyone who gave me advice on how to get educated about climate science. I know I said sites, but I’ll be reading good old fashioned books as well. Someone asked what colleges/universities I live near. Fortunately I live fairly close to Penn State University. They have a good meteorology program. I even used to read forcasts for Accu-Weather in State College a long time ago….but I digress.

I’m ready to dig in and learn. You guys have all been nice and very helpful. Thanks again.

–Guy

The Inconvenient Truth

54 t_p_hamilton,

Pinatubo erupted in 1991. Did you mean El Chichón, which erupted in 1982?

I think this is neat, that is Foster and Rahmstorf.

Does anyone know what causes the few large fluctuations that remain, e.g. 1982, 1983, 1984? I’m guessing “no” or else it would have been removed.

Is there an implicit or explicit claim that this linear trend (plus identifiable disturbances) will continue into the future? Can you decompose this into a part due to CO2 and a part due to whatever produced the rest of the increase since the 19th century?

51, Paul S: There was a large volcanic episode in early-1982 followed by an extreme El Nino in 1983 (comparable to 1998). I imagine these large overlapping competing factors, at that point and elsewhere, played havoc with calibration of the model which leaves the adjustments being useful but less than perfect.

Anyone else have an idea?

Foster and Rahmstorf (Figure 7) display the estimates of the effects of the MEI, AOD and TSI, but not the MEI, AOD, and TSI themselves, so you can’t determine from their paper whether a misfit to one or more of them is responsible for the swings that remain.

I don’t mean that as a criticism: I like what they did.

SM, in the paper you’re not-criticizing you say they did not include in the journal “the MEI, AOD, and TSI themselves, so you can’t determine from their paper ….”

What field did say you’re in?

How do they publish databases in your field?

On page 2 you’ll find “Section 2. Data” listing how to get what you’re not-complaining about not-having.

Guy McCardle, the (somewhat long) lecture series of D. Archer is notably informative of the basics, you probably find much of this familiar, but assuming you’re a biologist or of the medical sciences, you may find much of it new or at least something not normally thought of. Starting at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uHXpkoE0G3A&feature=relmfu

Also for SM — https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/data-sources/

75. Septic,

Tamino also tested an index based on pressure, but it didn’t change the results.

Here’s a graph with all three components. There is a disparity between the El Nino index and smoothed temperature after large eruptions, as it should.

#76 et seq–

The principal author said that there should be residual effects remaining, since the correction factor is a single value, applied across the entire data set. Hence extremes–such as the 1998 El Nino, for example–will be under-corrected.

The phrasing is mine, so any errors are not the fault of said author. . .

77, Hank Roberts,

That was really only a minor comment about Figure 7 and the relevance to guesses above about the remaining swings in figure 5 reproduced above. I didn’t say the data were unavailable, only that the answer to the question (was it the El Chichon eruption in 1982?) isn’t in the paper.

The links to the data sources, along with this and the Appendix permit someone to reproduce their procedure:

In fact for some of the data sets, the annual cycle in temperature during the time span under analysis has changed noticeably relative to that during its baseline period. Hence there is a residual annual cycle. This is greater for the data sets whose baseline period is distinctly different from the time period analyzed in this study. For example, Fourier analysis of residuals from a linear fit to GISS data during the period January 1979–December 2010 shows clear peaks at

frequencies 1 and 2 cycles yr1. To allow for a residual annual cycle in the data, we included in the multiple regression a second-order Fourier series fit to model an annual cycle, i.e., trigonometric functions with frequencies 1 and 2 yr1. This effectively transforms the adjusted data to anomalies with

respect to the entire time span, by adjusting the annual cycle to match its average over that period. Therefore the multiple regression includes a linear time trend, MEI, AOD, TSI and a second-order Fourier series with period 1 yr.

The influence of exogenous factors can have a delayed

effect on global temperature. Therefore for each of the three factors we tested all lag values from 0 to 24 months, then selected the lag values which gave the best fit to the data.

I don’t know why that goes in and out of italics.

So, what do you think about the possibility that the El Chichon eruption was responsible for the residual big swing in 1982, 1983, 1984? Nothing?

1980-1984? Doesn’t matter what I think, let’s look for some science. Well, where would you look?

I tried http://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=1980-1984+climate+cooling

From the first page, one paper looking at that span:

Are global cloud albedo and climate controlled by marine phytoplankton?

[PDF] SE Schwartz – Nature, 1988

http://www.ecd.bnl.gov/steve/pubs/Nature1988MarinePhytoplank.pdf

(Cited by 159 subsequent papers)

I like the way this reverses the rather bizarre logic of McLean et al 2009 who subtracted the linear trend then said, hey, presto, there’s only ENSO left. At least this is a real result, and one that includes some clear graphs that aid the nontechnical audience. Over here in COP-out-17 land, I’ve used this in what I hope is a clear presentation to the uninitiated. Comments and corrections there welcome.

One good leverage multiplier to have in ones logical toolkit when confronting deniers, is the very fact that those of us who had at least some education in geophysics of oceanography back in the 1970s’, all learned – and correctly so! – that the Earth was headed into another Great Ice Age!

This may sound like giving support to the denialist brou-haa-haa, but it actually drives home the Fact that the Full Impact of Human Climate Modification is actually staving off that very Ice Age – providing, of course, that we don’t turn off the Atlantic Conveyor……..I hear there’s some nice towns in Uruguay where the people speak Norwegian…..

Love Ya All.

Congratulations on a fine research paper. I think its very important to try to reconcile and unify the models to get as much agreement as possible. Even though the adjustments may no turn out exactly right, it puts a stake in the ground to explain at least one way agreement could be reached.

“I thought the 70’s-cooling mole had been well whacked, but no.”

http://scienceblogs.com/stoat/2011/09/global_cooling_again.php

84, Hank Roberts, you are correct: we should look at all omitted covariates; the paper only shows that the temperature series discrepancies can be reconciled, not that this is the correct or best way to do it. The authors used lagged versions of the regressor variables in their analysis, so in principal we should not ignore the possibility that the 1982-1983-1984 inflection was driven by an event that occurred in 1980.

It’s still a good paper.

Very stark reading indeed. What I find very singificant is the CO2 concentration rate leading up to the last interglacial period. By using ice core analysis and other means we are certain that in the lead up 130KY ago CO2 was increasing at an average of 0.0001ppm/y. Wait for it!…we are currently pushing the rate at 2.0000ppm/y a 20000 fold increase. This rate must surely set a paleoclimatic record. We are definately in uncharted waters as even Prof. James Hansen would attest to. The big difference between the last intergalcial period and now is that now the air/ocean temp is rising year round forced inextricably by the relentless pressure of CO2. 130000 years ago it was the change in juxtaposition between the earth and the sun that caused the polar regions to heat up (still only by 0.7C warmer that today)and then that caused CO2 to increase. The situation now is the reverse of what is was then. We are literally in greenhouse conditions now and this is causing a 24/7/365 positive feedback juggernaut. In the last I.G.P flora and fauna at least has a fighting chance to adapt and evolve..not this time. A 20000 times faster onset now is a stupendously massive shock to the earth’s climate and it’s ecology. Personally I’m not sure how useful any future predictions of global climate based on the last IGP can be simply due to the unprecedented speed of today’s onset. Do known and well documented physical processes still operate and behave as they are supposed to under today’s rate of change?

Perhaps I missed it while reading the paper, or I am simply to dense to have understood, but how did the authors weight the different forcings in order to adjust the data? To put things in my own elementary banter: When the TSI, aerosols or ESNO effect increased, the temperature values in the raw data sets were decreased, in order to modulate correct for the bias caused from that particular forcing, correct?.. Were the data sets treated on an individualistic basis, as the algorithms used to correct the initial raw data were different?

Does this result suggest, since in the paper for the last decade stratospheric aerosols are low/flat, and since TSI is relatively flat and has small effect, that the recent fluctuation of global temperatures is mostly ENSO related?

[Response: Short term (year-to-year) variability in global mean temperature is predominantly ENSO related at all times, and that impacts decadal trends as well. I don’t think that this is unique to this decade (though at each period the attribution would be a little different). – gavin]

Thanks, I guess from all that people talk about the last decade I thought it would have been something more dramatic!

Back when the seeds of this paper were being explored on Tamino’s ‘Open Mind’ blog I asked (under my pseudonym of ‘Ken Fabos’) –

Tamino’s answer was he didn’t know but the question should be put to ‘genuine’ climate scientists. (As if his own contributions are mere adjunct to the work of others!).

So, to the genuine climate scientists, looking at the peer-reviewed paper that resulted, is there an answer to that question?

[Response: Short term (year-to-year) variability in global mean temperature is predominantly ENSO related at all times, and that impacts decadal trends as well. I don’t think that this is unique to this decade (though at each period the attribution would be a little different). – gavin

Is there an estimate of total variability which is attributed to the parameters, how much is likely other causes, and how much is likely error?

And I kid you not, Captcha says “Richard otedxt”. I’ve never otedxted before.