The impending Obama administration decision on the Keystone XL Pipeline, which would tap into the Athabasca Oil Sands production of Canada, has given rise to a vigorous grassroots opposition movement, leading to the arrests so far of over a thousand activists. At the very least, the protests have increased awareness of the implications of developing the oil sands deposits. Statements about the pipeline abound.

There is no shortage of environmental threats associated with the Keystone XL pipeline. Notably, the route goes through the environmentally sensitive Sandhills region of Nebraska, a decision opposed even by some supporters of the pipeline. One could also keep in mind the vast areas of Alberta that are churned up by the oil sands mining process itself. But here I will take up only the climate impact of the pipeline and associated oil sands exploitation. For that, it is important to first get a feel for what constitutes an “important” amount of carbon.

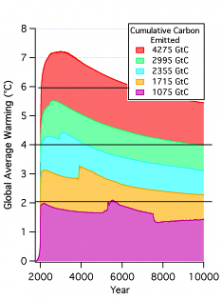

That part is relatively easy. The kind of climate we wind up with is largely determined by the total amount of carbon we emit into the atmosphere as CO2 in the time before we finally kick the fossil fuel habit (by choice or by virtue of simply running out). The link between cumulative carbon and climate was discussed at RealClimate here when the papers on the subject first came out in Nature. A good introduction to the work can be found in this National Research Council report on Climate Stabilization targets, of which I was a co-author. Here’s all you ever really need to know about CO2 emissions and climate:

- The peak warming is linearly proportional to the cumulative carbon emitted

- It doesn’t matter much how rapidly the carbon is emitted

- The warming you get when you stop emitting carbon is what you are stuck with for the next thousand years

- The climate recovers only slightly over the next ten thousand years

- At the mid-range of IPCC climate sensitivity, a trillion tonnes cumulative carbon gives you about 2C global mean warming above the pre-industrial temperature.

This graph gives you an idea of what the Anthropocene climate looks like as a function of how much carbon we emit before giving up the fossil fuel habit, without even taking into account the possibility of carbon cycle feedbacks leading to a release of stored terrestrial carbon

Proved reserves of conventional oil add up to 139 gigatonnes C (based on data here and the conversion factor in Table 6 here, assuming an average crude oil density of 850 kg per cubic meter). To be specific, that’s 1200 billion barrels times .16 cubic meters per barrel times .85 metric tonnes per cubic meter crude times .85 tonnes carbon per tonne crude. (Some other estimates, e.g. Nehring (2009), put the amount of ultimately recoverable oil in known reserves about 50% higher). To the carbon in conventional petroleum reserves you can add about 100 gigatonnes C from proved natural gas reserves, based on the same sources as I used for oil. If one assumes that these two reserves are so valuable and easily accessible that it’s inevitable they will get burned, that leaves only 261 gigatonnes from all other fossil fuel sources. How does that limit stack up against what’s in the Athabasca oil sands deposit?

The geological literature generally puts the amount of bitumen in-place at 1.7 trillion barrels (e.g. see the numbers and references quoted here). That oil in-place is heavy oil, with a density close to a metric tonne per cubic meter, so the associated carbon adds up to about 230 gigatonnes — essentially enough to close the “game over” gap. But oil-in-place is not the same as economically recoverable oil. That’s a moving target, as oil prices, production prices and technology evolve. At present, it is generally figured that only 10% of the oil-in-place is economically recoverable. However, continued development of in-situ production methods could bump up economically recoverable reserves considerably. For example this working paper (pdf) from the National Petroleum Council estimates that Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage could recover up to 70% of oil-in-place at a cost of below $20 per barrel *.

Aside from the carbon from oil in-place, one needs to figure in the additional carbon emissions from the energy used to extract the oil. For in-situ extraction this increases the carbon footprint by 23% to 41% (as reviewed here ) . Currently, most of the energy used in production comes from natural gas (hence the push for a pipeline to pump Alaskan gas to Canada). So, we need to watch out for double-counting here, because our “game-over” estimate already assumed that the natural gas would be used for one thing or another. A knock-on effect of oil sands development is that it drives up demand for natural gas, displacing its use in electricity generation and making it more likely coal will be burned for such purposes. And if high natural gas prices cause oil sands producers to turn from natural gas to coal for energy, things get even worse, because coal releases more carbon per unit of energy produced — carbon that we have not already counted in our “game-over” estimate.

Are the oil sands really the “biggest carbon bomb on the planet”? As a point of reference, let’s compare its net carbon content with the Gillette Coalfield in the Powder river basin, one of the largest coal deposits in the world. There are 150 billion metric tons left in this deposit, according to the USGS. How much of that is economically recoverable depends on price and technology. The USGS estimates that about half can be economically mined if coal fetches $60 per ton on the market, but let’s assume that all of the Gillette coal can be eventually recovered. Powder River coal is sub-bituminous, and contains only 45% carbon by weight. (Don’t take that as good news, because it has correspondingly lower energy content so you burn more of it as compared to higher carbon coal like Anthracite; Powder River coal is mined largely because of its low sulfur content). Thus, the carbon in the Powder River coal amounts to 67.5 gigatonnes, far below the carbon content of the Athabasca Oil Sands. So yes, the Keystone XL pipeline does tap into a very big carbon bomb indeed.

But comparison of the Athabaska Oil Sands to an individual coal deposit isn’t really fair, since there are only two major oil sands deposits (the other being in Venezuela) while coal deposits are widespread. Nehring (2009) estimates that world economically recoverable coal amounts to 846 gigatonnes, based on 2005 prices and technology. Using a mean carbon ratio of .75 (again from Table 6 here), that’s 634 gigatonnes of carbon, which all by itself is more than enough to bring us well past “game-over.” The accessible carbon pool in coal is sure to rise as prices increase and extraction technology advances, but the real imponderable is how much coal remains to be discovered. But any way you slice it, coal is still the 800-gigatonne gorilla at the carbon party.

Commentators who argue that the Keystone XL pipeline is no big deal tend to focus on the rate at which the pipeline delivers oil to users (and thence as CO2 to the atmosphere). To an extent, they have a point. The pipeline would carry 500,000 barrels per day, and assuming that we’re talking about lighter crude by the time it gets in the pipeline that adds up to a piddling 2 gigatonnes carbon in a hundred years (exercise: Work this out for yourself given the numbers I stated earlier in this post). However, building Keystone XL lets the camel’s nose in the tent. It is more than a little disingenuous to say the carbon in the Athabasca Oil Sands mostly has to be left in the ground, but before we’ll do this, we’ll just use a bit of it. It’s like an alcoholic who says he’ll leave the vodka in the kitchen cupboard, but first just take “one little sip.”

So the pipeline itself is really just a skirmish in the battle to protect climate, and if the pipeline gets built despite Bill McKibben’s dedicated army of protesters, that does not mean in and of itself that it’s “game over” for holding warming to 2C. Further, if we do hit a trillion tonnes, it may be “game-over” for holding warming to 2C (apart from praying for low climate sensitivity), but it’s not “game-over” for avoiding the second trillion tonnes, which would bring the likely warming up to 4C. The fight over Keystone XL may be only a skirmish, but for those (like the fellow in this arresting photo ) who seek to limit global warming, it is an important one. It may be too late to halt existing oil sands projects, but the exploitation of this carbon pool has just barely begun. If the Keystone XL pipeline is built, it surely smooths the way for further expansions of the market for oil sands crude. Turning down XL, in contrast, draws a line in the oil sands, and affirms the principle that this carbon shall not pass into the atmosphere.

* Note added 4/11/2011: Prompted by Andrew Leach’s comment (#50 below), I should clarify that the working paper cited refers to recovery of bitumen-in-place on a per-project basis, and should not be taken as an estimate of the total amount that could be recovered from oil sands as a whole. I cite this only as an example of where the technology is headed.

I apologize if this question has been answered upthread, but the article basically makes a 2C warming level the definition of defeat. I haven’t seen that point asserted so starkly before. (Note: I’m a layman, so a lot of what you folks talk about here gets past me. So be gentle.) I’m convinced of the science behind AGW, and I am disappointed at the way the issue has been portrayed in the popular press. But what is the significance of the 2C number? Most of what I read about trying to match particular outcomes to particular temperature increases has stressed the uncertainties.

So, simply put: what is the current thinking about how the Earth would be different with a 2C global tempo rise?

[Response: In the last paragraph, I try to make clear that there is no one number that magically denotes “defeat.” 2C is not a magic threshold. I quote it because it more or less corresponds to the target the EU settled on, by some mix of what seemed practical and at what level of warming the effects start to look scary (a subjective judgment). Think of it like a speed limit. If you go over 100km/h, you’re not guaranteed to get in an accident, and you’re not guaranteed safe below it either. But the faster you go, the more likely it is that something will go wrong, and the worse the consequences. You can get an idea of the rise in damages ‘by degrees’ by reading the executive summary of the NRC report on Climate Stabilization Targets, linked in the post. –raypierre]

Re#85 Jon Kirwan,

Yes, the utilities are happy to utilize storage from wherever, and if free from car batteries that is fine with them. There are some issues with that, but it could work out ok. And if cheap in the end it could make wind and solar a little less awkward to utilize, thus bringing the effective cost of these down somewhat. But this is about storage, not basic electric energy production.

Production of electricity still will come from fossil fuels, and these type of generating capacities stand ready to fill new loads. Renewable sources are instantly tapped out in most cases, and there is no reason to expect brighter sun, stronger winds, or more rain to jack up the renewable apparatus when the aggregate of new electric vehicles gets plugged in. We can expect more coal to be shoveled.

[Response: I think the discussion of electric vehicles has run its course, and seems to be degenerating into speculation and statement of personal opinions without much information content on either side. Enough, please. –raypierre]

From the article: “A knock-on effect of oil sands development is that it drives up demand for natural gas, displacing its use in electricity generation and making it more likely coal will be burned for such purposes.”

I note that this effect is similar as that resulting from California’s proud action to ban coal fired generation.

All involved are quick to deny that the elimination of numerous coal facilities put California in a precarious position with power, hence a trivial accident brought 6 million people to a screeching halt for about a day, on a hot day last September in Southern California.

re #102 raypierre,

Please note that logically supported statements are characterized as speculation and personal opinion when they run critical of the sacred electric vehicle.

Enough ok, but I do make a last appeal to those striving to be scientific to look at the EPA formula for MPGE for electric vehicles. It is not a personal opinion that this is an insult to science by denying the laws of thermodynamics by denying the effect of the heat engine that makes the electricity for the electric vehicles.

Raypierre,

With regard to the question “Did I read the post?” – I stopped soon after the part where you stated Bill McKibben has the better argument. This is the point of my question concerning credibility. McKibben is an activist with an agenda. Tying him into the subject is introducting politics into it. When the objective is to provide people with the science behind climate change, I would suggest this is something you would want to avoid. I have not paid much attention to the Keystome debate and seeing a post about it offered me the opportunity to increase my knowledge. Unfortunately, no matter how good your piece may be, I stopped reading because it was, at least in my opinion, contaminated. Your respecting Bill McKibben is fine. Whether one agrees with him or not, he has an impressive list of accomplishments. That you agree with his position on Keystone is fine as well. I am simply suggesting that it might have been better if you would have put forth your points and, at the end, said for these reasons I find McKibben’s argument carries more weight.

As for the train bit – a) I was not questioning the intrinsic value of trains and b) No, it does not show that some countries are better than others at managing big engineering projects. What the comment on high speed trains and fuel cell cars – just two of many supposed means to lower the carbon footprint – was addressing is the point that waving one’s hands and saying we don’t need fossil fuel energy because we have all of these better alternatives indicates either a lack of understanding of the true challenges, costs and hurdles associated with these alternatives or some underlying agenda. The belief that our society can be forced off of fossil fuels is false, unless one thinks that the majority of people are willing to make significant, even dramatic changes to their lifestyles. That won’t happen unless there is demonstratable proof that they are at grave risk if they don’t or someone scares them enough to think the risk exists.

Which brings me to where I am today – questioning whether or not I am on the right train. I work for a utility which relys primarily on hydro generation but is also one of the biggest developers of wind generation. We are switching our fleet to hybrid and all electric vehicles. I make my home in a city that is not only pedestrian friendly but has one of the best light rail systems in the country. I’m even working on getting back to biking like I used to. Are these a result of climate change concerns? With the possible exception of developing wind turbine generation – which is largely driving by tax incentives and a state mandate for renewables – no. But even the wind power part is justifiable on the basis of energy independence and the knowledge that fossil fuels are not inexhaustable. But now I see policies based on the arguments of catastrophic impacts due to climate change that could have a significant impact to me. An impact I would not consider favorable. So when the people I’ve been believing in start supporting this, without backing up the claims of catastrophic impact, and alaigning themselves with people having a clearly stated agenda (like Bill McKibben) which I am not all that in agreement with, I start thinking it may be time to get off at the next stop.

To summarize, you can side with McKibben all you want. Just don’t be surprised if the people you are trying to reach start wondering about you.

[Response: People have been “wondering about me” since I was two years old, maybe longer. I think I’ll manage. But I do appreciate your — concern. –raypierre]

#60 raypierre.

I wonder if you are referring to establishing standing forests as ‘direct air capture’?

If so, that could indeed function at a significant scale. I see 30,000 square miles, mostly on federal lands, as significant for capture area. Greatly enhanced agricultural productivity could make this a politically feasible project.

I did not get very far with discussing this here last year. But it still is a real concept. Much hostility erupted with the inclusion of the idea of water distribution on a continental basis in North America. But I did offer to let Canada do the oil sands if they would divert some of the fresh water southward, that they now dump into the salt oceans.

[Response: The problem with standing forests and similar agricultural carbon sequestration schemes is that they store carbon in a fairly labile form near the surface. It’s not at all clear how long that carbon will be sequestered. –raypierre]

I guess the line in the sand is really about whether low EROEI carbon energy sources will be tapped – at least when easily accessible and high efficiency oil/natural gas/coal that is easily accessible and converted to energy, the high value of burning these fuels at least probably means that even if we could factor in the generally unaccounted for climate and environmental impacts, mankind is likely still better off as a whole (although of course we might be even better off using a renewable energy source to achieve the same thing). If we start using these more marginal energy sources, with commensurately larger externalities per net unit of energy, it could quickly become the case that for every gallon burned of such oil overall everyone is worse off due to the lack of accounting for the externalities makes it still economically viable for the companies/individuals involved to do so.

Campaigners against Keystone might do well to give a serious read of: http://ecocentric.blogs.time.com/2011/04/25/battling-over-the-climate-war/

Then look again at the comparison of environmental damage of the mining itself and running a pipeline over environmentally sensitive Nebraska(?). There are, of course, a few more people around in Nebraska that might be bothered. But not many.

It is not really that hard to control what leaks from a pipeline. Of course, someone has to pay attention.

Raypierre,

I did go back and read the entire post. And have this question –

If one were to assume that the 500,000 barrels a day from Athabasca were to replace imported oil, isn’t that a good argument in favor of it?

Your point about energy requirements to recover and refine the oil is a good one and I can see that increasing energy usage may not be seen as a concern to the producers if the overall cost is less than recovering over fuel sources. In that sense, one can view the tar sands development as a move in the wrong direction on the basis of it’s adding to rather than lowering the amount of CO2 being generated.

[Response: No, it wouldn’t be a good thing, not so far as climate is concerned. The imported oil isn’t ‘replaced,’ it’s just burned somewhere else. That oil coming in over Keystone is oil that would be better off being left in the ground, so far as climate is concerned. but remember, its not the 500,000 barrels itself that’s the big deal. It’s the possible effect of that flow leading the way to more extraction of oil sands carbon. –raypierre]

I don’t know if this has already been linked to, but earlier in the comments Raypierre refers to Armour & Roe’s GRL paper “Climate commitment in an uncertain world”. There’s a pre-print available here, and a very imformative pdf of slides from Gerard Roe here.

Thanks for the main article, IMO it’s one of the most alarming and important pieces RC has published.

raypierre’s comment @31:

“One pipeline doubles the oil flowing to US refineries, generates more market, generates more capital to develop more oil sands, then demand for more pipelines and … well you get the picture. ”

I am not sure Andrew Leach would agree wholeheartedly with that scenario.

‘http://andrewleach.ca/oilsands/keystone-xl-and-us-energy-security-you-cant-have-it-both-ways/#more-818’

‘http://andrewleach.ca/oilsands/new-york-times-editorial-on-keystone-details-matter/’

Tar sands oil is already moving into the US. The goal of the pipeline seems to be to get more of that oil into the US South. If it does not go into the US it will go to Asia. But either way, the oil is going to be exported.

Re #101

The origin of the 2C limit is described by RealClimate here.

It is estimated that the 2C rise corresponds to a CO2 level of 400 ppm. The CO2 level is currently 392 ppm and increasing by 2 ppm per year.

Jim Hansen, shown in the arresting photo, reckons that 350 ppm is the maximum safe level, which means that we are already in the danger zone. He is probably correct because there is now no way to stop the Arctic sea ice disappearing and, unless we reduce CO2 levels, the Greenland ice sheet will continue to melt too. Moreover, without the Arctic sea ice, the Greenland ice sheet may melt even faster.

Reply to raypierre’s response @90:

I agree completely keeping it to 1 trillion tonnes vs. 2 trillion is important, and I do oppose the Keystone XL pipeline for several reasons. But I think a strong case can be made that 2C is already “baked into the cake” so to speak at the near 400 ppm, and the probability is probably higher that we will see both 560 ppm and at least 3C, and so we ought to take a stand to prevent going over that, because we can be more realistic about what kinds of preparations we are going to need to make for a world of at least 3C. How much more, for example, might the ocean levels rise in a 3C world versus a 2C? I doubt this is linear, and that difference could be huge for coastal cities. Make no mistake, getting off our carbon fuel addiction is certainly paramount, but, if we take this to the analogy of a junkie, we have to realistic about how much damage has already been done and is already in the pipeline to the system, as we ween the junkie off his carbon-fix. I think 2C is already there, and so putting our defenses up at 3C might be a better tactic.

Jim Bullis, if you think you can waste your own water on the assumption that you can import more from Canada, you are going to die of thirst.

Get it through your head: You can’t have our water. You can’t have our water. You can’t have our water.

Not even the water contaminated by the tar sands which is producing a higher rate of rare cancers among the people living there, as well as deformed fish.

#109 timg56 Canada is not part of the US. If you imported more tar sands oil, it would still be imported oil.

115 Holly Stick,

I get it that you would rather dump water into the salt-water oceans than share it. And you know, it is really hard to get it back after that.

You might not be right in assuming that water would be wasted. Of course it is in some places, but that needs to stop.

We do share the Great Lakes, last I looked. Hmm. But I was hoping for rational negotiations, and even some mutually beneficial arrangements of water distribution systems. Even Canadian farmers could benefit from some water distribution improvements.

Do you represent Canada?

raypierre and moderator jim,

Thanks for the conversation.

[Response: A pleasure, Jim. Keep coming back! –raypierre]

115 Holly Stick,

I left off my main point which is that perhaps the majority of Canadians are interested in solving global warming sufficiently to be willing to share water that could be important to achieve that end.

R. Gates (#114),

The trouble is that “we” have no effective defenses against aggregate global emissions to put up yet. Stopping a particular project here or there, maybe that could be done. In fact it needs to be done as part as building the defenses.

But any talk of drawing a line in the sand with respect to CO2 concentration or global temperatures before the fight has even started in earnest is mere political rhetoric. If it’s effective organizational rhetoric like 350.org, great.

Since 350 is already well in the rear-view mirror, I think it’s a good choice in that no one is going to be misled into actually trying to defend that line or into panicking because it’s been crossed.

Certainly it would be prudent for the bodies in charge to plan for a sea-level rise congruent with a long-term increase in average temperature of 3C or more.

But there are even more uncertainties as to the effect of a given rise in average temperature. Keep in mind that the major problem for many coastal cities is going to be the management of rivers rather than the sea level as such.

Check my link above to see how such early planning could look like. This 2008 report acknowledges the possibility of >6C by 2100 (implying more warming later) as per the relevant IPCC scenarios and models so I don’t think you should be overly concerned about planners assuming warming will be stopped at 2C. One doesn’t only plan for the best-case scenario.

I’d be more concerned about the planning for which no one is responsible yet.

Cornell Report Busts Myth of Keystone XL Job Creation

Pipe Dreams? Jobs gained, jobs lost by the construction of Keystone XL: A report by Cornell University Global Labor Institute (PDF)

http://www.skepticalscience.com/detailed-look-at-renewable-baseload-energy.html

From the skepticism on this subject about renewable energy, there is more education needed. It is difficult to jump into something you don’t know especially if you don’t believe in it.

From skeptical science there is an article to address 100% renewable energy. One of the important points to get to is that can we refine the different high temperature processes to make it beyond oil and coal that have done it so well in the past.

Fortunately we are headed in peak oil now and peak coal is soon to arrive. That is working for us economically. Some people here also read climate progress and there are now several articles showing that solar is decreasing in cost.

Another interesting point is that tar sands have an EROEI of 3, 5 to 1.

Solar single crystal is 9 to 1 from Home Power and thin film is 17 to 1.

Wind is 18 to 1. Oil which use to be 100 to 1 now varies around 10 or 20 to 1. I’m scratching my head wondering how they got tar sands down to $20/barrel when it used to be $60/barrel. They must be getting some pretty cheap natural gas to get their work done.

From the Oil Drum, there is quite a bit of conversation around the cost of oil creating recessions. The timing the price of oil during the Arab Spring and our last dip in the economy seems to hold true. As the costs go up, the United States groans because we are built on the price of cheap energy. What used to be our economic strength is now raising its ugly head.

Richard @112,

If Keystone XL is not built, how then does the oil get to Asia? Via existing routes? But can these routes handle the increased load? Or do you mean Enbridge’s proposed Gateway line to Kitimat, B.C? Or their propsed Monarch line from Chicago to the Gulf Coast. But is either one of these a sure thing? I don’t think so, not with more and more people waking up to the dangers of global warming.

It would be much worse to leave oil sands in the ground because the result would be coal to liquid fuels production(synfuel or methanol) on a massive scale. Compare the impact of electric blackouts to an oil embargo. If the US stopped coal consumption, US electric production would fall by 50% but reducing oil production by more than a few percentages and the world would collapse over night. At present consumption, conventional oil will last about 40 years and there is no alternative to petroleum (or bitumen) for the next 40 years at least. Unconventional oil at least will reduce the dangerous hold conventional oil has over the world.

“I left off my main point which is that perhaps the majority of Canadians are interested in solving global warming sufficiently to be willing to share water that could be important to achieve that end.”

What a load of passive aggressive BS. If you greedy so and sos have wasted your water while at the same time having caused global warming, don’t expect any other country to bail you out. I fail to see how you stealing our water would in any way solve global warming.

Water is necessary for life. There are no rational negotiations for giving that away.

The genie is out of the bottle. If they don’t send it south, they will find a way to sell it to Europe or China. Use it and tax it. These protesters should be focusing on getting a carbon tax. But that is out because it would lower our precious standard of living and force conservation.

Steve Funk (#125),

British Columbia already have a carbon tax. It’s world-famous actually. Other places have carbon taxes as well. Existing carbon taxes are poorly structured and are way too low but their existence demonstrates that this “no new taxes” mindset is plain denialism.

Raising taxes is also possible. It happened in the past and we know in general terms how to do it in a representative democracy: the taxes need to benefit a large constituency as well as to appear righteous according to the value system of that constituency.

Carbon taxes need not lower “our” standard of living. Maybe they would lower yours but definitely not everyone else’s.

Educate yourself first and only then move on to tell others what’s possible and what they should be doing. Some of the protesters you’re talking about are quite smart and well-informed, you know.

Apparently, there’s a law that every fuel, no matter how polluting, will be touted as an “alternative” to an even more polluting one.

What will jd (#123) and others come up with when it’s time to sell liquid coal?

Actually, no, you don’t have to do cocaine just because heroin is worse.

We can go on digging ourselves deeper into the hole we’re in, scraping the bottom of the oil barrel, replacing each exhausted non-renewable fossil fuel with an even dirtier one, until there is no longer anything to dig up and burn, or we are too hot and too hungry to bother, whichever comes first. Or we can work on real alternatives that might leave us with both energy and a planet to spend it on.

Cue Agent Smith, saying: “One of these lives has a future.”

The economic problem is that right now, those oil sands have a “value” that depends on the cost of extraction. All fossil fuel resources are “valued” the same way, with the costs for extraction and utilization accounted for, but the costs of CO2 mitigation not accounted for.

All of the fossil fuel resources that have such a “value” cannot be extracted and burned without putting unacceptable quantities of CO2 into the atmosphere. The “value” that those deposits have is a fiction, a fiction based on the delusion that all that carbon can be burned to CO2 and put in the atmosphere while the rest of the Earth and the rest of the economy remains unchanged.

The problem is the fictitious “value” that these fossil fuel deposits have. Because they have a “value”, they can be used as collateral to borrow cash, either as debt, or by selling stock. That borrowed cash can be used to buy things, like other companies, other investments. But if the “value” of the collateral falls, because the lenders realize that the carbon that is in the ground has to stay in the ground, then the whole house of cards collapses.

What is the “value” of 1.7 trillion barrels of oil sand oil while it is still in the ground? If we say it is only $20 per barrel, then 1.7 trillion barrels is worth $34 trillion. If only 0.1 trillion barrels can be extracted, then it is only worth $2 trillion. Who lost the $32 trillion asset?

This is the problem, the people who “own” the deposit or the rights to the deposit have an asset which they have borrowed money on and which they (and those they borrowed money from) think is a real asset.

What people who care about the future environment of this planet need to do is find some way of destroying the “value” of an “asset” of fossil fuel in the ground such that it cannot be used as collateral to borrow money either by selling stock or by taking on debt. Carbon taxes is one way of doing so.

123 jd: Yes we must prevent coal to liquid fuels production and coal to gas production.

127 CM: Roger that as well.

119 Anonymous Coward: 6 degrees C is the extinction point for Homo Sap.

350.org isn’t big enough to do it all. Strategy please?

daedalus@128. The arithmetic of potential gain is really compelling. What if the oil can be produced for $100/barrel below the market clearing price? Thats not hard to imagine: with increasing demand, and decreasing volumes available on the export market, prices in excess of $200/barrel are not beyond the pale, but quite possible. If $trillions are possible, and the population it could be shared with is only several million, greed is hard to defeat. It could litterally make an entire province wealthy. Hard to get local people to give that up for a global (and future) good.

Might need to look into that closer – the royalties paid to the province are minimal until capitol costs are recaptured, only then does income tax kick in – also the cost of living in the “oil patch” is out of reach for even most oil company workers. The only folks getting rich off the environmental rape there are the oil company executives and share holders, so “the population it could be shared with” is waaay less than “several million”.

I find a lot of narrow-mindedness in a discussion about transferring water willy-nilly around the North American continent that fails to acknowledge the needs of an entire ecosystem for ample water, and not just the needs of humans. To imply that allowing water to flow into the salty ocean is somehow a waste of water is completely denying the value of brackish water estuaries to the planetary ecosystems, just for starters. And since anthropogenic global climate change (AGCC) will actually increase the earth’s capacity to draw fresh water out of the salty ocean and dump it on the land, might this interpretation the water problems of a warmer planet be way over-simplified? I think we would be far better off concentrating more on the problem at hand: let’s all reduce our carbon footprint NOW, both from a personal point of view and through national political action, such as keeping tar sands carbon in the ground. Water conservation is another serious issue that AGCC, coupled with population growth, is going to compound enormously.

I’ll bet that I have better than halved my own personal carbon footprint over the past few years without reducing my quality of life in the least, and I’m just getting started! I have also significantly reduced my use of water at the same time. Change is possible, and it starts in the individual mind. Human thoughts are creative, which means that if you think you can’t, then you can’t. Science provides the light that will shine down any path we chose to take, whether it is the right one or not. But with a little light, it just might be possible to see ahead far enough to notice that some paths run right off the cliff!

Thomas,

People tend to overestimate the value that accrues to the population of a region from a windfall of natural resources. This is especially true for petroleum. What usually winds up happening is that a few individuals accrue tremendous wealth, while the region as a whole tends to benefit little, and perhaps be even worse off than before (viz. the Niger delta). People look at the wealth of Saudi Arabia, but fail to realize that what they are seeing is the wealth of the Saudi royal family and whatever crumbs they choose to brush off to the masses below. For small nations, the resulting demand for currency can inflate its value and strangle other industries (the so-called Dutch disease).

And then when the resources are depleted, the economy is left with no industry, no jobs, and the wealthy move on.

Ray, overestimation of benefits is a major problem. But, when we are dealing with human decisionmaking, it is perceptions rather than history that tends to drive things. A rich well governed province like Alberta probably thinks it will avoid those mistakes. The wealth in Saudi Arabia has been well enough distributed that its population has exploded severalfold. That is actually pretty frightening, if you consider what sort of population that land would support without massive oil revenues to pay for imported food.

“If Keystone XL is not built, how then does the oil get to Asia? ”

If the demand is there, the oil will get to Asia. Yes there are a number of alternative pipelines in the proposal stage; demand and price will be the determining factors in whether they go forward – both Alberta and Canada are addicted to the resulting revenues. It would be wiser to reduce demand thru a hefty carbon tax.

106 raypierre,

re standing forests, your ‘not clear how long it will last”, thanks for commment.

I did not get into details here about a forest and water project, but the fundamental rule is that the forest must be made to last. I imagine tying agriculture to forests, and making water available to growers, contingent on continuation of the forests.

After looking hard at orchards in the California Central Valley, I have been thinking that standing orchards could work also, if on aggregate there is a long term standing wood mass. That way orchards can be retired and replanted, but the net mass just has to continue forward.

The same rules could be used for managing mature forests.

The good thing about forests is that we know they work on a large scale, and they are a natural solution, albeit vastly expanded on lands hitherto unforested.

Special interest is currently appropriate since this could be a way to provide employment and generate positive foreign money exchange by sale of agricultural products.

Curiously, this has led to a new endeavor which is to build tools that make agricultural work more attractive, with the intention of enticing unemployed Americans to the ‘field’, including the incentive of increased productivity to encourage the growers to hire such folk.

Anyone advocating not building the Keystone XL is going to have to explain how we can create the vast infrastructure a renewable society requires without tapping every last drop of oil that is economically feasible. At least if they want to be taken seriously by serious people.

There are 2 curves that have relevancy in this conversation. The first is the change in price of fossil energy over time. The second is the change in price of renewables over time . Currently, the price of fossil energy is getting higher. The curve is sloping up. Renewables are going in the other direction. At some point in time the curves will cross. When they do, no force on this planet will be able to stop the mass adoption of renewables. By the same token, until the lines cross, the is no govt subsidy large enough or green protest massive enough to make adoption of renewables happen before the technology is ready to support our society.

I, for one, would like to hasten the day when those 2 curves crossover. Since the development of any and all technology is dependent on the availability of resources, it is quite *nonsensical* to believe that reducing the availability of the resources required (eg not developing the tar sands) will result in a quicker, more thorough adoption of renewables. It won’t. It will, in the simplest point of fact, delay the date at which the curves cross. Delaying this curve crossing date, even if it is to limit carbon uptake into our atmosphere will *without a doubt* cause more harm than good.

Let me put to you all this way-

Society is on a horse. The horse is fueled with carbon. A few days travel away is another food the horse can run on (renewables). What is going to happen if we stop feeding the horse before it has made its way to the new food? If the horse starves to death before it reaches its destination, it will *never* be able to eat the new food. Like it or not, if we want to get to the new food, we have to flog this carbon fueled horse for all its are worth until we crest that hill the renewables are hiding behind in the distance.

[Response: This “carbon flogging” is like the alcoholic who says he needs a drink to calm his nerves enough to get a job so he can relieve the stress that causes his drinking problem. There’s already enough enconomically recoverable fossil fuel (including the coal) to bring cumulative emissions well over a trillion tonnes. If you are going to say all that has to be flogged in order to make enough money to do renewables, you’re saying basically the game is lost before it’s even hardly begun. If we’re going to make the transition before hitting a trillion tonnes, some pathway needs to be found to do it, that allows almost all of the remaining coal and unconventional oil to remain in the ground. I’m not offering any easy solutions, but implementing a good number of carbon stabilization wedges would slow down emissions growth enough that we can figure out what to do. Andy Revkin is also right that a lot more investment in energy technology is needed. You’re not going to solve the problem by just burning more and more fossil fuels and hoping that the wealth created will just magically call the solutions into being. –raypierre]

Omni – I said this before, and I will say it again: The amount we are currently paying for carbon fuels does not reflect the true cost of those fuels to human civilization and world ecosystems. That cost is getting passed on to future generations, and, boy, are they going to be pissed at us when they get the bill.

So let me put it to you this way:

Society is on a horse. The horse will only eat carbon, although there are other fuels currently available that the horse could eat, but does not want to because he thinks they are “too expensive.” The carbon fuel is rapidly making him sick (which he denies), but if he keeps on eating carbon, he will die. So maybe the human rider, who controls his horse, and who we assume is actually smarter than a horse, might try changing the horses diet?

Science is clearly telling us what we need to do. We just need the courage (and that means positive thinking) to do it.

Greetings all. I want to start by saying Hi to everyone and say that as a first-time poster I am glad to find this particular discussion. I was raised in the town of Fort McMurray, which is where the oilsands are, my father worked at one of the main plants (Syncrude) until he retired and I worked for 1.5 years at the other (Suncor). Having been raised there I am always interested when the subject comes up although there really aren’t many forums where you can have an on-going thoughtful discussion about the subject.

Now despite having worked there, I am in 100% agreement with the goals of reducing emissions, limiting our use of fossil fuels and being very careful in general with making changes to the environment that we can neither control afterwards nor accurately anticipate consequences. The first thing I want to do is clear up, as best I can, some of what I perceive are mistaken notions about the oilsands development as I think it is critical to know what the battle is that we face if we have any hope of succeeding.

First I want to talk about the idea that production of the oilsands is related to this Keystone pipeline. The idea is, in my opinion, entirely false. The only thing that this pipeline affects is distribution, not production. Suncor went online around 1978 and Syncrude went online about 2 years later and the necessary pipelines to get their products to market were already in place at that time. By the 90’s they were combining to produce 500k barrels per day and today they have improved that somewhat to 600k to 700k barrels per day. The Keystone pipeline adds another possible destination, but there are already numerous ways this oil is getting into the US market. I believe, in fact, that the majority of it already makes its’ way into the US. It makes diesel, gas, naptha, kerosne and even plastics and if you have been driving for any length of time in the US I am fairly certain you have already burned some of the tarsand oil in your car. So you can oppose the pipeline for a lot of different reasons, but the notion that opposing it will somehow prevent the oilsands from being exploited is simply untrue. At the very best it may prevent the oilsands plants that exist from expanding, but even that claim is dubious.

Second I would like to talk about the ability of the Canadian government to affect anything here. Syncrude is largely owned by Exxon and they have taken a much more active management role in recent years. Suncor is owned by Sunoco. There is also a plant owned by Shell and then some small plants owned by China, Japan and possibly others (I do not live there anymore so I am not aware of all the plants anymore). The bulk of the production is Suncor and Syncrude though and the rest are mostly bit players in comparison. There are no Canadian plants that I am aware of. Although the Canadian government has always had an open door policy for anyone wanting to exploit our resources, NAFTA essentially codified our obeisance to foreign industry to the point that we are no longer allowed to say “No” to American companies that want to exploit our resources without subjecting ourselves to huge penalties, lawsuits, fines, etc. Granted the Canadian government was all too happy to enter into such bondage with the Americans but at this point, as far as power goes, the Canadian government has little more than token control over the land. The Albertan government has also shown enthusiasm for any approach that pulled more oil out of the sands and a reluctance for regulation and accountability that would probably please Ron Paul. So by choice and by law the Canadian government will make little difference in the outcome. Whatever business and foreign corporations want to do, it will be supported.

The third issue I would like to mention is the nature of the process and the product that is released. The process is roughly like this: It takes 2 tonnes of sand to make one barrel of oil. That sand, which looks like a big pile of dirt, is then put in the Primary Separation Vessel where it is given essentially a hot soapy bath. The main difference is that in this case it is the resulting bathwater that is desired. It is sent to a vertical centrifuge where it is spun fast enough to increase the force of gravity 300 times and, since the oil is lighter than the sand and water particles, the oil can be siphoned off to a horizontal centrifuge that repeats that process only on a horizontal axis rather than a verticle one. Then it is “cracked” or evaporated with high heat and re-condensed at a variety of temperatures to produce the various types of products. By this point we have a product very similar to what you are used to however it has a few difficulties that require some further refining. At Syncrude the resulting product is then blasted with hydrogen to remove the sulfer content (you should see the pyramid-sized mountain of sulfur they have onsite) and that is known as Syncrude Sweet Blend. Both Suncors and Syncrudes products are pretty well refined at this point and raw bitumen is definitely not being exported out of Fort Mac. (This makes no difference from an environmental stand-point I know but it a personal quibble I have since I always cringe whenever I read an article that says the bitumen is sent down the pipeline for refining). Now the tarsands that have been mined for the last 30 years is about 60 feet in height and thousands of square kilometers. It is right near the surface so the open-pit mines that extract it do not have to dig too deep. The machinery that is used is incredible. The extraction problem that they are facing today is that the tarsands are deeper and deeper the further north they go until, by the time they get to Lake Athabasca, the oil is about 2km down under a huge lake and a giant piece of bedrock known as the Canadian shield. That oil, even if the price were essentially infinite, could not be recovered by any process we know of today. The steam injection method where they drill into the sand inject steam and then pump the resulting water out for extraction (colloquially known as “Huff-and-Puff”) is still experimental and has lots of technical hurdles that prevent it from being all that effective (at least the last I heard anyway).

So, after all of that, my only remaining comment is that if you are concerned about the Carbon Bomb, as Bill McKibbon has put it, or the Game Over scenario as James Hansen as described it, I fail to see how the fate of the Keystone pipeline will make any difference at all. My own prediction is that every last barrel of recoverable oil is going to be pulled out of the sand and then that expertise is going to go down to Venezuela where they have an even larger oilsand field to make money on. I wish the climate warriors all the best in their fight, however. Take care.

89 raypierre: You are correct.

I receive emails that ask me to sign petitions or letters to congress. Some ask me to call congress or go to a local congressman’s office or write a letter to the editor. There is a web site that is a petition generator.

http://signon.org/

If I generate petitions, I think nothing will happen. Nothing is what happened with my Whitehouse petition. This conversation is so frustrating. It keeps going around in circles. [Will it or won’t it take another route.] Trying to run for the US congress was also frustrating. It seems like there is very little we can do, but my son tells me we are gaining.

http://www.credoaction.com has a lot of petitions.

The Occupy Wall Street started at http://ampedstatus.org/

350.org is the group protesting the pipeline.

Moveon.org starts a lot of petitions.

Since RealClimate wants to stick to science, I hope those other groups read RealClimate.

You’re not going to solve the problem by just burning more and more fossil fuels and hoping that the wealth created will just magically call the solutions into being. –raypierre]

I am not really saying (remember I didn’t say all the oil, I said just what oil is economically viable and don’t forget viability is a moving target!!! a target defined by 2 price curves, not just one like the analysis of 1 or 2 trillion tons you are using assumes) that and am most certainly not meaning to imply it either! Not saying we shouldn’t adopt all reasonable (reasonable=eroei return greater than whatever the current carbon based eroei is) measures to push the day of no return farther away. We *should* adopt all measures that show energetic viability. Not saying that directed investment in R and D is a bad idea either. It isn’t.

What I *am* saying is that the horse we are riding needs to be fed *every* day. Not feeding the horse results in hobbling the horse or in severe circumstances, death. If the horse is hobbled, reaching the destination(destination=carbon neutrality) takes longer, and even more carbon will be consumed in that extended, longer process! In the worst case scenario of premature fossil disinvestment, the carbon fed horse actually dies before we reach our destination and our destination will not be reached. This event is to be avoided at all costs. Do not put your applecart before this horse.

Discontinuing the investment in the old infrastructure before the new infrastructure is ready is a horrible error. How are we to smelt the steel and copper for the wind turbines? How will we create the silicon for the solar panels? How will we refine the the rare earths and lithium needed for viable electric cars? If you truly believe we can bring forward the day carbon neutrality arrives by hamstringing the industry that is required to achieve it, you’re just flat out wrong!

Also, on a side note, the link between wealth and technological growth is *most* assuredly not magical in the least. Technology creates wealth and in turn more wealth creates more technology. Again, in simple point of fact, this positive feedback loop is what got us to where we are today. By saying this process is “magical” you are saying what? That our technology and the resulting wealth don’t actually exist? Or are you saying this process is somehow broken and scientists are no longer smart and engineers are no longer clever? Are you saying entrepreneurs are no longer greedy? What exactly do you mean when you imply technological advancement is somehow *magical* and not the natural result of an intelligent creature interacting with its environment?

Also, I am not saying we shouldn’t do everything we can to mitigate climate and energy issues in our personal lives. I ride a scooter in the summer and I drive a hybrid. My tires are always aired up my main mission when I drive somewhere is to use as little fuel as possible in that process. My home is also well insulated.

Also, the alcohol/addiction analogy is quite tired and was never particularly apt to begin with. Again in simple point of fact, energy is required for life, alcohol is not. Are you addicted to eating? Are you addicted to sleeping? Can you explain to me how I can sleep in my house if it is not heated in the winter? Can you explain how I am going to be able to eat if the farmer who made my food can’t get diesel for his tractor or fertilizer for his fields?

Also, saying “some pathway must be found” and then declaring a couple sentences later that I use magical thinking isn’t a very convincing debating choice, to say the least!

Best hopes for a climate stable future for our children!!!

Omnivorous Rex

PS-Sorry about the length of this response. Wanted to answer all your points.

[Response: And can you explain to me how we’re going to eat in 2100 when the coal runs out and we’re trying to grow food in the heat you get from 5000 gigatonnes cumulative emissions? Could happen sooner (though with proportionately lower temperatures) if there’s less coal than that. Wouldn’t it be prudent to have policies that nudge things in the direction of doing without fossil fuels without waiting for the day the hard landing is practically upon us? I’m no better than anybody else at predicting what kind of nudge would work, and won’t go into that here, but there are plenty of ideas around. –raypierre]

Thomas #134 [off-topic],

I don’t want to start an OT discussion on this, but 1) data on wealth distribution in Saudi Arabia are generally “not available” (which in itself is rather telling), and 2) there are no grounds for assuming that high population growth reflects equality in the distribution of wealth (incidentally, nearly one third of S. Ar.’s population are migrant workers). The absolute monarchy’s bid to trade some oil wealth for social and political peace by keeping much of its native population so to speak on welfare is not just ecologically unsustainable; the social cracks are showing, too.

omni #127,

In your model there are two curves which represent price over time. Prices are affected by supply and demand so measures which affect supply or demand (like the Arab oil embargo) alter the curves. If you alter one curve, their crossing point changes. That’s very simple math you’re arguing against!

#137–Moreover, increasing the (effective) supply of fossil fuels is *not* the way to “hasten the day when those 2 curves crossover,” since presumably doing so would have the effect of lowering FF prices.

The comment as a whole seems to argue that relative prices are sensitive to technological factors and nothing else–which is certainly not true. And in the real world, the “govt subsidy” of renewables via a FIT has had very large and obvious effects on the deployment of renewables already–as in many billions of dollars of investment, the establishment of renewables technology as a viable industrial sector globally, and over a hundred gigawatts of installed generation capacity.

Finally, the throwaway clause, “before the technology is ready to support our society,” seems to me both unsupported and tendentious. I think the technology is basically ready NOW, and that the transition is underway.

(For clarity, when I say “basically ready,” I don’t exclude that practical developments are still needed for the technology to qualify as fully mature–but looking at history, I don’t think any significant technology ever fully matured “on the shelf.” Operational experience, technical refinement and economic integration happen as a consequence of projects existing in the real world, not on the drawing board–however interactive and sophisticated the “drawing board” may now be.)

“Discontinuing the investment in the old infrastructure before the new infrastructure is ready is a horrible error.”

And it’s a “probability zero” scenario, too. Can’t and won’t happen, both due to economics and common sense. But that doesn’t mean that policy choices–say, an internationally-coordinated carbon tax–can’t nudge those curves in a desirable direction.

I think the key insight some commenters might be lacking is how huge the scale of current fossil fuel consumption is.

A commenter above referred to the fuel used by the tractor used to grow his food. Relatively, that’s a very small amount. You could offset such amounts with Jim Bullis’ standing forests (I did the math last year: his proposal could unfortunately not possibly offset the current consumption) or similar carbon sequestration projects.

From the point of view of what’s technically possible today and regardless of one’s opinion about the potential of renewables (I’m not as optimistic as most), most of today’s fossil fuel consumption is a waste. It’s a tragic waste not only because of the pollution but because it’s a vital limited resource which is being depleted senselessly.

With the current price structure, the waste makes sense for individual agents trying to make a quick buck. That’s why the price structure needs to be changed. And that’s not a technical issue. It’s a political issue.

A couple of reactions to this post; one from Michael Levi, an economist who tends to agree with Andrew Leach (or vice versa):

http://blogs.cfr.org/levi/2011/11/06/keystone-xl-jamaica/

And Keith Kloor, with some pretty good discussion in the comments:

http://www.collide-a-scape.com/2011/11/07/the-big-picture-2/

146 Anonymous,

Your statement that ‘my’ standing forests could not possibly offset the current consumption might assume too much about the bounds of ‘my’ forest, and also limit it to whatevery type of tree, root structure assumptions and such that you would have made. It also mis-represents my initial premise which posed the notion of standing forests to compete with ‘carbon capture and sequestration’ of the sort being discussed by the EPA to be applied to new coal fired generation – – not offset current consumption.

But thanks for doing the math. That could be useful in working on the concept. Yes, something that big would need to go further than my initial premise. But there is much flexibility in the extent it could be undertaken. Involving both massive forests and greatly expanded agriculture still looks possible as a major new economic system.

146 AC

To your noting the ‘tragic waste’, that also has to be fixed. No, forests can not balance gluttony of the sort we practice.

Political issues are handled by lobbyists and public markets for fashionable products. No hope can be held for changing things here.

I see more chance for change when there are new choices. Here is where there might be possibilities for new thinking. Here though, real progress in motor vehicles is snubbed off by false thinking about electric vehicles.

OK, this is by way of a cruel oversimplification, but something like this needs to be said.

Raypierre says we need to leave huge amounts of carbon in the ground to avoid gargantuan risks.

Omni says we probably won’t get very far very fast with renewable infrastructure without big investments that spend FF energy.

They are both right.

No one should take omni’s point to mean that BAU is OK. We’ve done that for 30 years, and it is working badly. Ray’s point (#141 inline answer) about policies to nudge things away from FFs is steering in the right direction. I would express the point with something stronger than “nudge”.

The best path is more like triage amidst loss than shiny solutions that all will applaud.

Omni, you should pay more attention to your own arguments. It is true (lately) that FF costs generally increase and renewables decrease. A rosy assumption that all will be well when the curves cross ignores the fact that the curves so far have existed in an environment of plentiful FF. We know rather little about costs of renewable infrastructure in a world of drastically constrained FF use. What we are sure of is that today we don’t build renewable infrastructure without cheap FF.