The impending Obama administration decision on the Keystone XL Pipeline, which would tap into the Athabasca Oil Sands production of Canada, has given rise to a vigorous grassroots opposition movement, leading to the arrests so far of over a thousand activists. At the very least, the protests have increased awareness of the implications of developing the oil sands deposits. Statements about the pipeline abound.

Jim Hansen has said that if the Athabasca Oil Sands are tapped, it’s “essentially game over” for any hope of achieving a stable climate. The same news article quotes Bill McKibben as saying that the pipeline represents “the fuse to biggest carbon bomb on the planet.” Others say the pipeline is no big deal, and that the brouhaha is sidetracking us from thinking about bigger climate issues. David Keith, energy and climate pundit at Calgary University, expresses that sentiment here, and Andy Revkin says “it’s a distraction from core issues and opportunities on energy and largely insignificant if your concern is averting a disruptive buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere”. There’s something to be said in favor of each point of view, but on the whole, I think Bill McKibben has the better of the argument, with some important qualifications. Let’s do the arithmetic.

Jim Hansen has said that if the Athabasca Oil Sands are tapped, it’s “essentially game over” for any hope of achieving a stable climate. The same news article quotes Bill McKibben as saying that the pipeline represents “the fuse to biggest carbon bomb on the planet.” Others say the pipeline is no big deal, and that the brouhaha is sidetracking us from thinking about bigger climate issues. David Keith, energy and climate pundit at Calgary University, expresses that sentiment here, and Andy Revkin says “it’s a distraction from core issues and opportunities on energy and largely insignificant if your concern is averting a disruptive buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere”. There’s something to be said in favor of each point of view, but on the whole, I think Bill McKibben has the better of the argument, with some important qualifications. Let’s do the arithmetic.

There is no shortage of environmental threats associated with the Keystone XL pipeline. Notably, the route goes through the environmentally sensitive Sandhills region of Nebraska, a decision opposed even by some supporters of the pipeline. One could also keep in mind the vast areas of Alberta that are churned up by the oil sands mining process itself. But here I will take up only the climate impact of the pipeline and associated oil sands exploitation. For that, it is important to first get a feel for what constitutes an “important” amount of carbon.

That part is relatively easy. The kind of climate we wind up with is largely determined by the total amount of carbon we emit into the atmosphere as CO2 in the time before we finally kick the fossil fuel habit (by choice or by virtue of simply running out). The link between cumulative carbon and climate was discussed at RealClimate here when the papers on the subject first came out in Nature. A good introduction to the work can be found in this National Research Council report on Climate Stabilization targets, of which I was a co-author. Here’s all you ever really need to know about CO2 emissions and climate:

- The peak warming is linearly proportional to the cumulative carbon emitted

- It doesn’t matter much how rapidly the carbon is emitted

- The warming you get when you stop emitting carbon is what you are stuck with for the next thousand years

- The climate recovers only slightly over the next ten thousand years

- At the mid-range of IPCC climate sensitivity, a trillion tonnes cumulative carbon gives you about 2C global mean warming above the pre-industrial temperature.

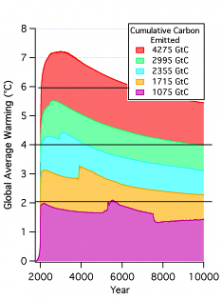

This graph gives you an idea of what the Anthropocene climate looks like as a function of how much carbon we emit before giving up the fossil fuel habit, without even taking into account the possibility of carbon cycle feedbacks leading to a release of stored terrestrial carbon

Proved reserves of conventional oil add up to 139 gigatonnes C (based on data here and the conversion factor in Table 6 here, assuming an average crude oil density of 850 kg per cubic meter). To be specific, that’s 1200 billion barrels times .16 cubic meters per barrel times .85 metric tonnes per cubic meter crude times .85 tonnes carbon per tonne crude. (Some other estimates, e.g. Nehring (2009), put the amount of ultimately recoverable oil in known reserves about 50% higher). To the carbon in conventional petroleum reserves you can add about 100 gigatonnes C from proved natural gas reserves, based on the same sources as I used for oil. If one assumes that these two reserves are so valuable and easily accessible that it’s inevitable they will get burned, that leaves only 261 gigatonnes from all other fossil fuel sources. How does that limit stack up against what’s in the Athabasca oil sands deposit?

The geological literature generally puts the amount of bitumen in-place at 1.7 trillion barrels (e.g. see the numbers and references quoted here). That oil in-place is heavy oil, with a density close to a metric tonne per cubic meter, so the associated carbon adds up to about 230 gigatonnes — essentially enough to close the “game over” gap. But oil-in-place is not the same as economically recoverable oil. That’s a moving target, as oil prices, production prices and technology evolve. At present, it is generally figured that only 10% of the oil-in-place is economically recoverable. However, continued development of in-situ production methods could bump up economically recoverable reserves considerably. For example this working paper (pdf) from the National Petroleum Council estimates that Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage could recover up to 70% of oil-in-place at a cost of below $20 per barrel *.

Aside from the carbon from oil in-place, one needs to figure in the additional carbon emissions from the energy used to extract the oil. For in-situ extraction this increases the carbon footprint by 23% to 41% (as reviewed here ) . Currently, most of the energy used in production comes from natural gas (hence the push for a pipeline to pump Alaskan gas to Canada). So, we need to watch out for double-counting here, because our “game-over” estimate already assumed that the natural gas would be used for one thing or another. A knock-on effect of oil sands development is that it drives up demand for natural gas, displacing its use in electricity generation and making it more likely coal will be burned for such purposes. And if high natural gas prices cause oil sands producers to turn from natural gas to coal for energy, things get even worse, because coal releases more carbon per unit of energy produced — carbon that we have not already counted in our “game-over” estimate.

Are the oil sands really the “biggest carbon bomb on the planet”? As a point of reference, let’s compare its net carbon content with the Gillette Coalfield in the Powder river basin, one of the largest coal deposits in the world. There are 150 billion metric tons left in this deposit, according to the USGS. How much of that is economically recoverable depends on price and technology. The USGS estimates that about half can be economically mined if coal fetches $60 per ton on the market, but let’s assume that all of the Gillette coal can be eventually recovered. Powder River coal is sub-bituminous, and contains only 45% carbon by weight. (Don’t take that as good news, because it has correspondingly lower energy content so you burn more of it as compared to higher carbon coal like Anthracite; Powder River coal is mined largely because of its low sulfur content). Thus, the carbon in the Powder River coal amounts to 67.5 gigatonnes, far below the carbon content of the Athabasca Oil Sands. So yes, the Keystone XL pipeline does tap into a very big carbon bomb indeed.

But comparison of the Athabaska Oil Sands to an individual coal deposit isn’t really fair, since there are only two major oil sands deposits (the other being in Venezuela) while coal deposits are widespread. Nehring (2009) estimates that world economically recoverable coal amounts to 846 gigatonnes, based on 2005 prices and technology. Using a mean carbon ratio of .75 (again from Table 6 here), that’s 634 gigatonnes of carbon, which all by itself is more than enough to bring us well past “game-over.” The accessible carbon pool in coal is sure to rise as prices increase and extraction technology advances, but the real imponderable is how much coal remains to be discovered. But any way you slice it, coal is still the 800-gigatonne gorilla at the carbon party.

Commentators who argue that the Keystone XL pipeline is no big deal tend to focus on the rate at which the pipeline delivers oil to users (and thence as CO2 to the atmosphere). To an extent, they have a point. The pipeline would carry 500,000 barrels per day, and assuming that we’re talking about lighter crude by the time it gets in the pipeline that adds up to a piddling 2 gigatonnes carbon in a hundred years (exercise: Work this out for yourself given the numbers I stated earlier in this post). However, building Keystone XL lets the camel’s nose in the tent. It is more than a little disingenuous to say the carbon in the Athabasca Oil Sands mostly has to be left in the ground, but before we’ll do this, we’ll just use a bit of it. It’s like an alcoholic who says he’ll leave the vodka in the kitchen cupboard, but first just take “one little sip.”

So the pipeline itself is really just a skirmish in the battle to protect climate, and if the pipeline gets built despite Bill McKibben’s dedicated army of protesters, that does not mean in and of itself that it’s “game over” for holding warming to 2C. Further, if we do hit a trillion tonnes, it may be “game-over” for holding warming to 2C (apart from praying for low climate sensitivity), but it’s not “game-over” for avoiding the second trillion tonnes, which would bring the likely warming up to 4C. The fight over Keystone XL may be only a skirmish, but for those (like the fellow in this arresting photo ) who seek to limit global warming, it is an important one. It may be too late to halt existing oil sands projects, but the exploitation of this carbon pool has just barely begun. If the Keystone XL pipeline is built, it surely smooths the way for further expansions of the market for oil sands crude. Turning down XL, in contrast, draws a line in the oil sands, and affirms the principle that this carbon shall not pass into the atmosphere.

* Note added 4/11/2011: Prompted by Andrew Leach’s comment (#50 below), I should clarify that the working paper cited refers to recovery of bitumen-in-place on a per-project basis, and should not be taken as an estimate of the total amount that could be recovered from oil sands as a whole. I cite this only as an example of where the technology is headed.

@raypierre’s response in 19 [Response: The comment about the Chinese is a red herring. …]

Unfortunately raypierre you have it wrong in this case. The real red herring here is XL Pipeline. People are duped into believing that stopping the XL pipeline will make a difference when the real problem is the use of coal generated power plants around the world to meet an unrestrained world demand for electricity.

Seriously? You realize that if it doesn’t go via Keystone, it will be pumped west and go to China and other countries in Asia who are starving for oil. In other words, it won’t remain “in the ground” regardless of whether Keystone is built. Would you rather have it shipped in from the Middle East instead? That is where your argument takes us to.

raypierre,

Is there a reason for the spike in global temperature out at ~4000-6000 yr for the relatively low emission scenarios, after the T anomaly has already begun to decay? It’s only a couple of tenths of a degree, but I imagine there’s a reason for a model produced it.

[Response: Oh, those spikes. Somebody else mentioned it earlier but I didn’t know which graph he was talking about. In the UVic model, they come from flushing events in the southern ocean, which affect ocean heat uptake and release. They haven’t been studied much, and the UVic ocean model is fairly low resolution, so I wouldn’t put a lot of credence in these fluctuations. They are interesting, though, and need to be followed up in full ocean-atmosphere GCM’s. –raypierre]

Those estimates ignore the fact that coal mine productivity has been falling since 2000. 25% in the US and the numbers are even more grim elsewhere.

A single US coal miner produces 12,600 tons of coal per year. His Chinese counterpart produces 505 tons per year.

Nuclear,wind and hydro are already cheaper then burning coal in most of the world. What is lacking is the industrial and human infrastructure required to roll them out quickly and effectively.

The tar sands will be developed and mostly exported to world markets. If Keystone is scrapped, the oil will go to China and other countries. If absolutely necessary, the oil will be refined in Alberta with products exported to the U.S. Possible groundwater contamination is a separate and important issue, but people who think the tar sands will stay in the ground if they protest loud enough are delusional.

An important factor seems to be unappreciated. While it’s probably true that if we nix the pipeline, the tar sands oil will end up shipped elsewhere, there’s still a meaningful social, political, and psychological impact if the U.S. rejects the pipeline because of climate change. It’ll be the very first time the U.S. said “no” in a situation where it really amounted to anything.

The minutemen at Lexington and Concord didn’t make any real dent in the British military dominance of the American colonies — but they did indeed fire the “shot heard round the world.”

Mike H wrote: “If Keystone is scrapped, the oil will go to China and other countries.”

And if Keystone is built, the oil will go to China and other countries. That’s the whole point of building a pipeline to the Gulf Coast where facilities for refining and exporting the oil already exist.

Raypierre is correct that the issue of who ultimately burns the tar sands oil — China, the US or whoever — is irrelevant. It makes absolutely NO difference to the Earth’s climate.

So, those who are offering the argument that “without Keystone XL the oil will go to China” are really arguing that “somebody, somewhere, is going to extract and burn the tar sands oil, no matter what”.

Which may well be true. In which case, I think James Hansen is right — it’s “game over” for any hope of avoiding globally catastrophic warming. Not only because of the direct impacts of Keystone, which this RC article addresses — but because of what that scenario implies for the trajectory of GHG emissions from all fossil fuels over the next decade.

We need to stop burning ALL fossil fuels as quickly as possible. If, instead, we are going to go full tilt into digging up and burning as much of the worst, most destructive, most toxic and polluting fossil fuels as possible, then we can forget about “stabilizing” the atmosphere at the already dangerous levels of CO2 that we have today.

Re #17 response by moderator jim, and #17

As I tried to point out previously, there is a complicated situation to consider.

It would be very helpful to market development of a very efficient car if the oil sands was blocked and coal mining stopped. Prices of both gasoline and electricity would go up and there would be higher demand for the such a car. Electric vehicles such as we now are seeing emerge will be costly to operate without great subsidies, and public tolerance of such subsidies will hit its limit. So if there is to be mobility, it would depend on very efficient forms thereof. And that is a market I could find very profitable.

However, I take no comfort in such foolish prospects. Though it might be a great business climate for Miastrada products, the economy could be so miserable there would be little left of the devoped world life to enjoy.

[Response: Jim, I think you could have your cake and eat it more easily than you think. Sweden has a much lower per-capita carbon emission than the US, their economy is booming and innovative, and if you take a look around Medborgarplatsen on a Saturday night you don’t get much feeling that those people are having a miserable time of it. Denmark also experienced strong economic growth even during periods when they were making progress on carbon emissions, though the recent economic crisis has to some extent put on the brakes. France is a somewhat similar example, in that people seem to be having a grand old time and enjoying life despite their per capita carbon emissions being only a quarter of the US. It’s not as clear cut an example though, since there is high unemployment and some signs of stagnation in their economy. Those who know France, though, know there are lots of other factors at play besides energy policy. –raypierre ]

Despite what some people here and oil company representatives say, if Keystone XL is scrapped it is actually unlikely that the bitumen will instead go to China. The political opposition in British Columbia to the Northern Gateway through Kitimat and expansion of the Kinder Morgan pipeline through Vancouver is much stronger than any opposition to KXL in the US. Native groups oppose the Northern Gateway pipeline and BC voters are firmly opposed to the prospect of 200 supertankers per year through the pristine fjords and islands of BC’s north coast. The Kinder Morgan proposal will involve increased tanker traffic through Vancouver (“Canada’s greenest city” and where the current mayor has expressed opposition to the project) and the Gulf Islands (where Elizabeth May, the leader of the Canadian Green Party was recently elected). See here and here. So, the argument that scrapping Keystone won’t make a difference is simply not true. Bitumen exports from Alberta will be restricted.

To be sure, preventing Keystone won’t shut down bitumen extraction in Alberta but it will slow it down, which is second best.

#10 moderator jim

Yes, the operative word is ‘fantasies’.

It is a question relative to the notion that fossil fuel based energy sources can be stopped by appeals based on climate change threat.

It is also a question relative to the notion that technologies such as solar, wind, and electric vehicles are viable when they require on-going subsidies to support their existence. (Quick start subsidies can be ok — note the distinction from ‘on-going’.)

Things that I fantisize on are first contingent on a prospect of economic merit, at least some hope thereof. Big thinking, especially out-of-the-box big thinking, is easily dismissed as fantasizing.

So what about revisiting the possibility of widespread stimulation of plankton, even though there was an experiment showing some eating of the plankton by zooplankton? (I have no sense of confidence in my spelling here.) The revisiting needs to be with intent to work with the observed realities and still accomplish results. (And by the way, the formation of calcite shelled creatures in warmer waters might not be as well estimated as a CO2 capturing process in general- – and yes, I understand the concern about reduced alkalinity of sea water due to CO2.)

Economic merit here is that such stimulating of plankton sounds like an inexpensive process that could be justified more easily than most endeavors by international agencies. Ensuing growth of fisheries could be a benefit to justify such action.

[Response: There is actually a lot of ongoing work on plankton stimulation by iron fertilization as a means of accelerating ocean uptake of CO2. One of the issues there is that it is very hard to demonstrate that any CO2 that disappears from the upper ocean is actually buried in the deep ocean, rather than at fairly shallow depths where it comes back within decades. There are questions about the effects fertilization would have on ocean ecosystems (the Gulf dead zone being a good example of too much fertilization being a not so good thing), but people are indeed working on it. My personal take is that the area that is underfunded is direct air capture, which would be a real game-changer. There is work on this, but not at the scale that would be justified by its potential importance if it ever becomes possible. Nobody should bet on direct air capture and sequestration to solve the problem, since the technology is so uncertain, but I think it belongs in the portfolio of research since it’s one of the things that could conceivably come through for us (even though it would be foolish to bet the house on that possibility). –raypierre]

[Response: I’m not apriori against any potential solution. However, generalized rule #1 of ecosystem manipulation, learned the hard way from much past experience, is: don’t alter important drivers unless you know exactly what you’re doing, because you will be likely be surprised at what happens, relative to what you thought was going to happen.–Jim]

Jim Bullis wrote: “Electric vehicles such as we now are seeing emerge will be costly to operate without great subsidies”

I see no reason to think that. On the contrary there is every reason to believe that electric cars can be, and will be, dirt cheap to purchase and to operate.

The electric cars “such as we now are seeing” are the first generation. The original 1981 IBM PC (with an 8 Mhz 8-bit processor, 64 Kilobytes of RAM, a single 360 Kilobyte floppy drive and no hard drive, and a monochrome text display!) cost over $7000 in today’s dollars. Look what you can get today for one twentieth of that amount.

As with personal computers, electric cars designed around industry-standard form factors and interfaces, and economies of scale will drive down prices, even without the technological “breakthroughs” (eg. dramatically improved batteries) that are already in development.

The argument that stopping Keystone XL is a variant on an increasingly common argument that since doing anything will not be fully successful immediately (springing from the head of Zeus, so to speak) we should do nothing. People should beware that the many-headed hydra of the fake skeptic PR machine is constantly developing new ways to divert the conversation. Secular Animist (among others) has covered the specifics above but in general getting us all to go down these tempting byways is part of the game. Doing nothing protects massive subsidies to existing profit centers and minimal subsidies to clean energy. I don’t need to mention that the latter is exactly what we need, sooner than soon.

Aside from the physical benefits of not creating a massive and probably dangerous pipeline 1700 miles long to bring extreme fuel to a port where it will be exported worldwide (Canadian firm is already working on “taking” individual properties, thanks to our wonderful Supreme Court who ruled some years ago that it’s OK to use eminent domain for profit.)

Anyone who hasn’t seen it would do well to read Elizabeth Kolbert’s article:

http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/11/12/071112fa_fact_kolbert

It is simply not true that the project is not highly destructive. There were wildfires nearby this year too (Slave Lake). Zooming in on the map you can easily see the scars of the tar sands project.

An important discussion here, but we should broaden it to the larger picture.

Transporting ffs is bad.

Burning ffs is bad.

Extracting ff is bad.

Of course, opening up whole new areas of ever-dirtier ff is particularly bad, but really we have to be marching in earnest in the direction of ever less (and ultimately essentially no) extraction, transport or burning of any sort of ff.

We are already way past the safety zone of 350 ppm (probably itself too high). We need to be planning and enacting ways to cease any more UN-sequestering of stored carbon and working toward effective ways to draw down the current, too-high CO2 levels in the atmosphere.

We should not even have to discuss whether this pipeline is a good idea. Instead, we should be figuring how to very rapidly stop all use of ff in ways that causes very bad negatively effects the fewest people.

But as Gore said long ago, the politics is in a very different place than the science is.

re #58 raypierre inline

I quite appreciate the value of studying other countries ways.

Some key differences though, France does half the CO2 that we do by having undertaken nuclear power on an overwhelming scale. They also embrace far more diesel vehicles, smaller at that than here in the USA. Shorter travel distances exist, and much higher gasoline and diesel prices are clearly wiser government policy. Note that we can’t even manage to cut off the oil depletion allowance, which I see as a far more likely event than anything curtailing oil and coal on a more significant scale.

Could we transition to a way of life as accepting of austerity as the Danes and Swedes seem to accept? Lifestyles there are not unappealing, though I suggest this notion is the greatest fantasy of the day, since it would require erasing of the USA distributed living and working arrangements that most have chosen.

Recently having seen Bergen Norway it was surprising to note that that city moved from a urban system confined by mountains to a suburban system with multiple tunnels through the mountains as soon as big money from oil showed up in the National coffers. My point is that people really choose distributed living when they have the option. So applying this rule to the USA, where the choices were made long ago, it must be seen as a difficult and unlikely notion that this would be reversed.

[Response: You are very misinformed about the Danes and Swedes. I have spent a lot of time living in Sweden, and “austerity” is not a word I would apply to their style of life. (That was partly the point of my remark about Medborgarplatsen, but if you haven’t spent time down in Söder, maybe that remark went past you and a lot of others). Affordable medical care, a transit system that gets you comfortably where you want to go, good livable urban design, great restaurants, countryside in proximity to cities, two months vacation, paid time off for more than a year for child care, widespread ownership of summer cottages, time off at holidays to spend with family, well gee if that’s austerity, I wouldn’t mind a bit more of it. –raypierre]

#62 Susan Actually, despite its name, TransCanada is an American company:

http://creekside1.blogspot.com/2011/10/transcanada-american-company.html

Re: what happens to our quality of life if we remove oil from the energy equation? One man’s real-life experience: I purchased a Nissan Leaf and have PV panels on my roof which provide all my house and Leaf energy (~10K kWh). Given that I needed a new car anyway, I ignore the $350/mo lease for the Leaf. But, I do know that I have an extra $250 to $300/mo in my pocket because I do not pay Costco for gas any more. This $250-300/mo plus the $100/mo I save on my house electric bill has an ROI for the PV in about 3 years. After that I have free energy for the house and car. I kept the ’97 Ford Escort as the back up gas-car, which is rarely used. My financial bottom line is better, my quality of life is at least the same, if not better. Does that translate to your situation? I do not know, but the calculations are a lot easier than those for climate models, that’s for sure!

Andrew Nikiforuk on some of these issues:

“…Environment Canada estimates that total carbon emissions from the oil sands will likely grow from 49 million tonnes today to 92 million tonnes by 2020. At that point the dirty industry will surpass the emissions of Canada’s buildings, agriculture or entire passenger car fleet. It will also exceed the carbon emission of more than half of 50 U.S. states south of the border…”

http://thetyee.ca/Opinion/2011/11/03/Oil-Sands-Ethical-Challenges/

Andrew Leach tends to argue that Nikiforuk gets some things wrong, but I think he has a lot to say that is valuable.

60 raypierre inline

Thanks for info on plankton studies. On that, why does it matter where the calcite from plankton ends up? Deep ocean is great of course, since there it would be out of reach of being digested in acidic stomachs, if that was an issue.

Direct capture of CO2 from air seems hard to imagine on a scale that would matter. And after capture, what? I am aware of an attempted Wind Fuels project that would utilize excess electric energy from wind sources in a process that captured CO2 and turned out motor fuel in the process. I think they would be grabbing more concentrated CO2 from power plant stacks. The CO2 would be returned to the air of course, but the net gain would be in oil not burned. Even here, the net CO2 removal rate is not huge.

#60 jim (moderator) inline:

I quite agree about hazards of tinkering. Here though, I see the various economies of the world, developed and otherwise, as being ecosystems themselves. The question of the day is whether actions that seem intended to cancel the Industrial Revolution are not tinkering of a serious sort also.

Whether there will ever be complete certainty in generalized action, I doubt. But some element of risk is probably necessary for any right action to come about. Finding a balance in judgments about such things is not going to be easy.

61 Secular Animist

Uh, not again, the Moore’s Law for electronics being applied to cars?

Start the Moore counter in 1900 when electric cars were well defined, and not that much different than now. We should be zipping about like space age fantasies like to show it, you know, ‘beam me up Scotty’.

Moore’s law has not even been relevant for power semiconductors, which have also not changed on that scale since the power MOSFETs of 1960s.

Electric motors? Tesla Motors uses the 100 year old Nikolai Tesla invented induction motor. Brushless DC motors utilize power semiconductor switching to make a real improvement, though brushes are not all that bad.

Dirt cheap? Uh, look at the economics of Lithium. In modest quantities it can be produced from a few (maybe two) mountain lakes in Chile-Argentina area. Getting it out of its abundant resting places is vastly more expensive. That is the biggest impediment to dirt cheap. The other is that the moving mass of the car as we know it is costly for many reasons not related to its engine size, or its motor in the electric form.

But the real problem is that fundamental energy required to quickly move the customary bluff body is large, whether it comes from a heat engine carried in the car or a heat engine in a central power plant.

Yes, an electric motor in a vastly different body form has possibilities that could be quite inexpensive – – not ‘dirt cheap’ though.

Re: electric vs gasoline car affordability. I think it is humorous that people who argue that oil-burning cars are less expensive than electric cars manage to exclude the cost of that oil.

Here is the cost to buy gasoline up here in Canada for a fuel sipping Honda Civic:

$15k at 2000 Canada prices

$20k at 2006 Canada prices

$30k at current Canada prices

$50k at current UK prices

$55k at current Netherlands prices

For a big SUV like the kind that clog our streets today, double those numbers to $60k – $110k for gasoline alone. And note that this doesn’t count the cost of the car itself.

So an SUV today runs over $110k for car plus gas and somehow the Leaf is too expensive?

With gas prices heading ever upwards and record oil profits linked to rising oil prices, you don’t need Moore’s Law to see electric cars as the future even if all you care about is lowest cost.

Nice post; I am confused about one thing though. Why does it not matter how fast the Carbon is emitted. Surely, it must matter, because we have soem sinks, including vegetation, soils, and ultimatley the gradual burial of dep sediments. The rate at which carbon is emitted will surely affect the imbalance between emissions and the rate of uptake by the various sinks. Doesn’t a faster rate of emissions ultimately mean faster rise in atmospheric concentration?

[Response: Faster emissions growth does give you a faster temperature increase, but with fixed net emissions, doesn’t much affect the climate you wind up with at the end. Even the effect on rate of temperature increase is somewhat muted by the response time of the ocean. The Journal of Climate paper by Eby et al (cited in the NAS study I linked) has some nice comparisons of instantaneous emission vs. gradual emissions, that make the point well. –raypierre]

“One of the issues there is that it is very hard to demonstrate that any CO2 that disappears from the upper ocean is actually buried in the deep ocean, rather than at fairly shallow depths where it comes back within decades.”

Another issue is depletion of phosphorus and other nutrients in the water… so you fertilize in one region which was iron-limited (but phosphorus rich), see local CO2 uptake, call it quits, and not only does the CO2 that got gobbled up come out decades later, but somewhere dozens of miles downstream, you’re getting reduced plankton growth and reduced uptake because the incoming water is now phosphorus depleted.

Yeah. Messing with ecosystems is all about the unintended consequences.

Thanks Holly Stick, can’t go back and fix it but if I could I would. That’s interesting, but selfish greed is international and lives are being destroyed. I got some stuff from the NYTimes and was too lazy to get the link. I was appalled at the idea that people are already losing their properties – the one I remember was Texas but there were at least a couple of others.

What Tamino said:

@156 3 Nov 2011 at 1:12 PM

I would like to point out (since he is not responding to me directly) that Jim Bullis’ statement:

“It is also a question relative to the notion that technologies such as solar, wind, and electric vehicles are viable when they require on-going subsidies to support their existence. (Quick start subsidies can be ok — note the distinction from ‘on-going’.)”

is based on a hidden fallacy. That fallacy is that the price of carbon-based fuels actually reflects their true costs to human society. As long as people like Jim Bullis deny these costs and don’t support pricing fuels based on the damage they do to the environment, carbon-based fuels will always be cheaper than cleaner technologies. It is a circular argument, so that those companies with huge infrastructure investments in carbon-based fuels can continue to maximize profits while continuing to avoid paying for the damage those fuels cause to the environment.

Which is why it is so important that expensive infrastructure like the Keystone XL pipeline never gets built.

To get a sense of the size of Alberta’s oilsands reserves, they contain five times more carbon than all of Canada’s coal reserves.

That compares what is currently economically recoverable using existing technology for both Alberta oilsands (72 GtCO2) vs Canada’s coal (13 GtCO2).

The oilsands have twice as much carbon that can be recovered using current technology but need a higher oil price to make economic. What is the chance of oil prices going up?

And the head of Shell estimates oilsands could release over 1,000 GtCO2 with new technology.

In 1990 the carbon extracted from the oilsands equalled 3% of the carbon burned in US coal plants. Today the oilsands have exploded to 14% of US coal burning.

The oilsands industry has plans for 10% increase in carbon extraction per year, leading to 6m barrels a day by 2035 which would be over one GtCO2 annual by then just from one carbon source in one part of Alberta. All fossil fuel burning in Canada today is about half that much.

McKibben is exactly right this this is a “carbon bomb” exploding. Hansen is correct that adding a new carbon bomb of that size to the carbon cycle is “game over”.

For all those folks who say Canada won’t allow it all to be sold, all I can say is fine, have Canada set a sane maximum limit on total carbon that will ever be allowed out of the oilsands. The fact they refuse to discuss such a limit tells you everything you need to know about how safe it is to let this project explode any more than it already is.

I’ve got no love for the oil sands and would rather have them stop production from it, largely because the world doesn’t need another source of any scalable oil, not just bitumen-based oil. Having said this, focusing on Keystone as a way to stop oil sands production is probably not the way we should be going about this, for numerous reasons.

1) Far more of the emissions come from burning the gasoline and not the upstream production of the bitumen. This whole Keystone-focused opposition is a very large investment of time and resources for only a small reduction in overall emissions, simply the gap in the market would be filled with oil would originating from somewhere else. This time and effort could probably be far better spent on something else (more later)

2) As has been said elsewhere, the bitumen and synthetic crude oil (SCO) will find another way to a market whether in North America or internationally. Commonly cited is China through ports on the west coast of Canada, with the bitumen getting there via pipelines. Sure, it’s not slam dunk that the pipelines will get approved by the federal regulator (there is tremendous opposition, including from pretty much every First Nation along the pipeline routes and who uses the coastal waters), but should the regulator deny the application because of the opposition, the federal cabinet as the power to overrule the regulator and, currently, is very pro-business. Almost certainly, there will be pipelines to the west coast of Canada. It’s been a growing key message of theirs over the past few years.

Alternatively, the crude can be shipped via rail anywhere in North America, west coast, Gulf Coast, and east coast. And once it gets to the Mississippi River, it can get down to the Gulf Coast via ships.

3) Far more efficient is to simply reduce demand for oil through big-P policy making. How did the world reduce CFC production? By going after individual projects? By targeting infrastructure? No. It simply banned them. Something similar can happen for oil by levying carbon taxes. Make it more expensive to use and the market will sort it out pretty quickly about where we get our oil from.

I should also say that, unless demand is attacked, oil consumption will continue to rise. As we’re finding out with tight oil now in the Bakken, as is being applied across North America and will certainly be applied around the world, there’s no shortage of oil to burn. Big-P policy making can take care of this in one fell swoop, by discouraging the use of any oil. Frankly, this is where we should be spending our time and energy.

[Response: I don’t see the point you are making in #1. My carbon accounting includes both the carbon released by the fuel user plus the upstream production emissions, with most of the focus on the former. –raypierre]

Americans and Europeans should conserve and consume less fossil fuel energy. Demand 60 mpg cars, eat less meat, invest in renewables and cut usage whilst driving up efficiency and even work from

Home if u can

Re #76 Miguelito,

It looks to me like you are correct in your #1. It looks like raypierre is thinking that by stopping the pipeline this will also stop use of oil in the amount that the pipeline would carry, including like oil from elsewhere. Your premise that the oil will simply come from elsewhere is entirely realistic. In raypierre’s words, ‘carbon released by the fuel user’, this is the the constant in the situation.

So yes, it is a practical matter that there must be measures that reduce the demand if any progress is to be expected.

re #77 Pete best

Fantasiast Bullis suggests actually accomplishing the goal for CO2 reduction from vehicles with a goal of 150 MPGE (honest equivalent for electric vehicles) for automobiles. Similar reductions for trucks are also on the Fantasia plan. It is a frightening thing indeed to see how this sort of thing could be accomplsihed at the miastrada web site. You add the dot com part. (Nothing for sale – – it is only a marketing study at this point.)

Re#70 Barry Saxifrage,

I am not sure if you are thinking electricity is free.

But it is really cheap now; guess why, it is because the cost of electricity the world over is pegged by the cost of coal. Electricity from renewables is ‘free’- – of course you know better.

Renewables as a source of electricity do not even figure in the equation since they are not remotely close to being in a position to handle load variations such as would be involved with electric vehicles. Natural gas power generation exists with reserve capacity that can handle this added demand, but only as long as cost of that is very low can governments trick rate payers into paying the extra cost of using such. And we might expect that tolerance for such burdens will diminish as the economy worsens.

So when I see future costs, as long as coal is the cost driver, you are right, electric vehicles will be cheap. So it could be an easy change, and look for plug-in SUVs to be coming soon. (But not until batteries get cheap; that is the real cost impediment for now.)

As far as CO2 goes, this is not a good thing.

I’m curious if you have any concern regarding credibility? You giving so much weight to the opinion of Bill McKibben calls this into question. Professor McKibben is certainly well known and has written extensively on issues related to the environment, but by his own account is an activist not a working scientist.

Were someone with solid academic credentials, like McKibben’s, come out with a report, or statement saying that the potential health and environmental risks of the project were minimal, would you as readily accept that position? To not recognize that a well known environmental activist has as much of an agenda as someone funded by an oil company is in my opinion evidence of either great naivity or reflective of having one’s own agenda.

I also was caught by a reply in the comments section where you refer to high speed trains as found in France. I recall seeing recently in the news that the project in California is way behind schedule and already exceeded budget by 100%. Which is not surprising with even the barest understanding of our nations rail transportation system or for anyone who has ever had to get any sort of infrastructure project built over long distances. Just as with the fuel cell car – where the properties of H2 require a complete rebuilding of the nation’s fuel distribution and supply infrastructure – basic engineering and financial issues exist which will not disappear simply because we manage to stop all carbon combustion.

People who have to deal with supplying the nation’s energy have to deal with these problems. I don’t think McKibben cares. But then he can afford not to care.

[Response: Did you read the post? I have a lot of respect for Bill McKibben’s judgment, but none of the numbers in my post come from Bill McKibben. In fact, I wrote this so as to help people make sense of the various claims being made about the significance of the carbon pool involved. So now you know that yes, the amount of carbon is a big deal indeed for climate, but that there is also a significant question about how much of the pool will prove economically recoverable (but that there is no grounds for a priori dismissing the possibility that most will indeed be recovered). Don’t you find that useful? Your remark about high speed trains just goes to show that some countries know how to handle big engineering projects better than others. It has nothing to do with intrinsic properties of trains as a means of transportation. –raypierre]

Raypierre:

My point is that, by focusing on the small wedge of increased emissions because of mining and in-situ production when compared to more conventional production, we can end up neglecting that most emissions come from the tailpipe. You might save a little bit of CO2 from being emitted by singling out the oil sands, but that oil is going to be replaced by oil from somewhere else not accounted for in proved conventional reserves (either increased reserves in existing fields, undiscovered oil, shale oil, or other sources) and the overall emissions don’t go down by that much.

While I love Realclimate, I don’t think I’m a big fan of this post. Maybe it’s that you guys set a really high standard and I balk when I see something on the unrealistic side. It’s a dubious assumption that this entire resource will be exploited. 50 per cent recovery of the 1.7 trillion barrels of oil in place and producing at 5,000,000 barrels per year would have this resource last for 466 years – how realistic of an assumption is that? At 10,000,000 barrels per day (a real stretch that it will ever get that high), it would be 233 years. Is that any more realistic?

Will we be using it to refine into motor-vehicle fuel for any significant amount even beyond 100 years? Certainly not in any policy driven world, especially as climatic effects of continued fossil-fuel use become apparent. Further, would your assumption make it into a reputable scientific journal? Certainly not in any case except for a high case (disaster scenario), and not as a most likely case. The most likely case would be much, much less.

I’ll repeat, I love this website. But I don’t think the climate community (scientists and policy makers) is being well served by this kind of post. It’s not particularly constructive.

[Response: The wedge is small now, but demand for oil is huge and the pool the wedge taps into is huge and significant. Why should we bet the planet on your gut feeling that production will inevitably stay small? –raypierre]

Sorry, I meant 5,000,000 barrels per day, not per year. 5,000,000 per year would be entirely unrealistic on the low side. Woopsie.

So, Canadian tar sand development, even though it produces considerable damage to the environment, would probably not really add much carbon to our atmosphere because there is just not that much oil commercially available from this source. It is just a drop in the bucket, so let’s do it!

US oil shale is just like tar sands, insignificant, so let’s do it!

Mountain top removal in West Virginia may cause serious damage to the watershed, but population density of the state is low and the total carbon added to the atmosphere is just a drop in the bucket, so let’s do it!

Deep water drilling for oil has the potential for causing serious ecological damage, but there is a lot of technology that will reduce the probability of this from happening, as we have already seen, and burning the oil derived from this source will add only a little to the total amount of carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere. It is just a drop in the bucket. Why not?

Drilling in ecologically sensitive areas, such as in Alaska, can probably be done safely and the amount of oil would produce additional carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that is just a drop in the bucket. So let’s do it!

Just a drop in the bucket? Drip, drip, drip. Steve

Re #80, Jim Bullis, “Renewables as a source of electricity do not even figure in the equation since they are not remotely close to being in a position to handle load variations such as would be involved with electric vehicles.”

I recently had a conversation with the engineer in charge of special projects at Portland General Electric (PGE, not to be confused with California’s PG&E.) They are nearly drooling at the idea of electric cars. He said that they hope to build in the intelligence at the home/car so that they can use these cars as an energy “store-and-forward” system. For them, the great boon is that they wouldn’t have to pay for the capital costs!! They’d just arrange “benefits” that would encourage participation in the longer term. But they’d reap big, at first, not having to lay out capital costs in the front end and they’d control the entire payout scheme so that it works well for them all the way to the bank.

I gathered from listening, and I think this disputes perhaps some of what you are suggesting, that they see these cars as leveling out variations at the generating stations. So on the contrary, reading his excitement during that hour’s discussion with him, it may be the electric cars that put them into a better position, not worse. They seem to have worked the figures out and like what they see.

I do want to partially refute the point about the oil being diverted to China instead of going south being a red herring. I’m not so convinced that oil exports are going to remain as fungible as has historically been the case. Those who buy into the production, via investment likely get access at preferential prices. Also the price varies regionally based upon local supply and demand issues. Note the absurdity of quoting the oil price as the West Texas Intermediate price in Cushing Oklahoma, whereas in almost the entire rest of the world the price is $20 or more higher. This is a case of being on the end of an increasing spigot, caused by increasing production of the Bakken (N Dakota mainly), and some tar sands oil, and limited export capability. Of course the benefit from access to some cheaper oil goes to the corps not the common man. In any case, who owns the means of production and transport, and where they are physically located does matter economically. This may not matter much in terms of net global emissions, but politically it could be signficant. And I fear reactionary forces will take advantage of any hardship that can be plausibly blamed on environmentalists.

I don’t dispute that thre is a dangerous amount of carbon in unconventional sources, and delaying or slowing their production could buy time for alternatives to become competitive.

BTW. shipping oil via train is not very effective, even a medium sized pipeline carries much more volume that a railroad line can handle.

Cost of electric vehicles, is dominated by the batteries. Unless there is a dramatic breakthrough in battery tech, the only path to affordable electric cars, is to downsize the vehicles.

I don’t think this kind of analysis is that helpful. The vast majority of economically recoverable oil is going to be extracted and consumed in the next 100 years. That ship has sailed. Hopefully we save two hundred billion barrels or so for plastics. How much coal is burned and how fast natural gas is consumed are the only remaining questions. Activists should try to focus the minds of policy makers first on levelling the playing field for different energy sources then recovering societal costs (eg health related costs due to coal burning) that are now ignored. The world is not prepared to make large economic sacrifices at this time, and making carbon miners pay their fair share is the low hanging fruit.

[Response: You’re not making sense. If you want to be a defeatist about prospects for climate protection, but if you’re flatly going to say that the vast majority of economically recoverable oil is going to be extracted, you might as well say the same for economically recoverable coal. What’s the difference? All I did in this “analysis” is to point out that the amount of carbon we’re talking about in the reserves tapped by the Keystone pipeline is a very climatically significant amount. If you don’t find that helpful, you have no respect for numbers. –raypierre]

There appears to be an assumption that a global warming of 2 K will somehow be bareable. I seriously doubt that. The changed patterns of drought and rainfall appears likely to put an end to a sizable portion of existing agriculture.

We have around 0.8 K warming so far and the effects upon agriculture (and the distruction of civil structure fro flooding) is already quite apparent. I conclude that even 2 K warming will be horrid.

49 Andrew Leach has a point about why not demonstrate against coal emissions instead. Could somebody clarify why the KXL pipeline was chosen as the thing to demonstrate against?

[There is a lot of coal too. If we could get coal shut down completely……] Is it really numbers or really symbols?

57 SecularAnimist: “We need to stop burning ALL fossil fuels as quickly as possible.”

Agreed. The problem is what do we mean by “as quickly as possible?” To people who own fossil fuel stock, “as quickly as possible” means as soon as the fossil fuels run out in a few centuries. What I mean by that phrase is about 5 years for coal. What Raypierre means is “keep the total under the trillion ton mark.”

As Tamino says, the pipeline is a symbolic thing, not that big in actual size?

Or is it that coal is already common, so coal is harder to stop?

Does winning on the pipeline imply winning on another source of carbon? Is it a political momentum thing? Is the choice arbitrary?

[Response: Protest against coal emissions instead? Why do you assume it’s either or. I can think of at least one notable climate scientist who has the distinction of having been threatened with arrest both in a coal protest and an oil sands protest. There are plenty of protests against coal, so that’s hardly being neglected. The plain fact of the matter is that if we’re to stay short of the trillion tonne limit, almost all of the remaining coal needs to stay in the ground, AND almost all of the nonconventional petroleum needs to stay in the ground. A tall order to leave it there, but there you are, no two ways about it. –raypierre]

Just a general question related to trying to keep global temperature increases under 2C. Considering the paleodata seems to show that when fast and slow feedbacks are considered, at the 400 ppm that we are approaching, we are likely already into mid-Pliocene type warming in a few hundred years at most, which generally is over the 2C of warming. 2C seems already unrealistically low. Maybe 3C or 4C is closer to something we can actually prevent?

[Response: Pliocene warmth is one of the more disturbing indications that climate may be more sensitivity to CO2 than our climate models predict. While it’s possible the geochemical estimates of Pliocene CO2 are off, barring that possibility the Pliocene indicates higher climate sensitivity than the mid-range IPCC models. That may in part be due to slow feedbacks like vegetation change (Carbon cycle feedbacks are not an issue here since it is the estimated CO2 concentration itself that is used as the basis for estimating Pliocene radiative forcing). So yes, my 2C is based on just the middle-range IPCC estimate, and a trillion tonnes could buy you a lot warmer climate, either through slow feedbacks not included in the models, or things like cloud feedbacks coming in at or beyond the high end. A trillion tonnes is not an especially safe place to go, but it’s a lot better than two trillion tonnes. –raypierre]

84, Steve has it right. Each individual decision is just one drip, but there are 7 billion of us making such decisions. Individual producers will produce as long as oil sells for over $10 (mideast) to $30 (tar sands) a barrel, while individual consumers will consume as long as oil is priced less than $150 a barrel. Saying no to an individual project does make a statement, but it won’t change the math. A 400% difference between the highest cost producer’s willing-to-sell price and the average buyer’s willing-to-purchase price is just too large to deny in a free marketplace. Renewables don’t solve much by becoming cheaper than $150/ barrel equivalent. Instead, they have to get cheaper than $30 a barrel, as that’s the threshold where fossil fuel production will start to decline. The alternative is a $100/barrel equivalent carbon tax, which would drive the price of crude to perhaps $40 for the producers while keeping the cost to consumers at $140, thus allowing the market to work its magic. The nice thing is that there isn’t any real cost involved. The $100 doesn’t disappear, and it can be redistributed, much as James Hansen has suggested. A $100/barrel carbon tax phased in over 10 years would make keystone unpalatable economically, and economics is the most efficient way to drive decisions. Of course, the vast majority of the planet would have to agree to implement, and perhaps enforce by embargo, such a drastic scheme. Not likely to happen until people get truly scared about global climate change.

In the meantime, what we can do is prevent the sinking of capital into projects like Keystone. Keystone also represents the enabling of further capital investments in tar sands extraction. Building Keystone is a decision which can’t be undone without the loss of all that capital. And with all the right-of-ways paid for, adding a second larger pipeline would be almost imperative from a profit standpoint as in-situ extraction comes online. Thus, building keystone almost guarantees that tar sand operations will greatly increase in scope and go on for 50 years. That’s 50 years where the US and Canada will have no business telling Venezuela, South Africa, and others to not develop their own little carbon bombs.

Many of you are posting about strategical issues. Tamino’s pithy #56 makes the two central points (namely that this is a political conflict and that it hasn’t started yet). I urge you to read it again and ponder it.

As others have explained, the ultimate amount of fossil C emissions is indeed not going to be decided tommorow or next year. In fact it won’t be decided before we’re all dead. And yes, keeping emissions low enough to avoid a dire catastrophe will most likely require sacrifices people are currently not willing to accept (Ray, the current Swedish emissions level is way too high).

But the marginal political victories which can perhaps be achieved in our lifetimes as well as the large emissions reductions which could be achieved with little effort by the world’s top emitters will shape the future. They would lessen the terrible burden on the next generations and put them in a better position to fight the battles that will decide the climate of the twenty-second century. Yes, people do care about the twenty-second century (see for instance http://www.deltacommissie.com/en/advies ).

[Response: Well, in some sense everybody’s emissions are way too high, in that fossil fuel emissions have to go to essentially zero at some point in order to avoid continued warming. Reducing emissions rates allows more time to figure out how to decarbonize the economy, so it’s useful. Sweden’s per capita emissions are 1.6 tonnes C per person, down from 3.1 tonnes C per person in 1969. US per capita emissions are 5.3 tonnes C per person, down only about 10% from their peak value in 1975. Getting the US down to Sweden’s per capita rate wouldn’t get us all the way to where we need to go eventually, but it sure would help, especially in view of the large and rapidly growing population of the US. –raypierre]

Two relevant posts by Joe Romm;

1. Additional carbon released from peat as permafrost melts not accounted for in Ray’s analysis.http://thinkprogress.org/romm/2011/11/03/360902/peatlands-feedback-drying-wetlands-wildfires-boosts-carbon-release/

2. No sign of global CO2 emission rate decreasing http://thinkprogress.org/romm/2011/11/03/361158/biggest-jump-ever-in-global-warming-pollution-in-2010-chinese-co2-emissions-now-exceed-uss-by-50/

#52: “Seriously? You realize that if it doesn’t go via Keystone, it will be pumped west and go to China and other countries in Asia who are starving for oil.”

Seriously? You think that building Keystone will somehow magically prevent any from being pumped west?

Tar sands distribution needn’t be a binary proposition–unlike the decision whether or not to make a massive investment in a technology we desperately need to wind down.

Here’s a nice summary of the state of play for CO2 air capture.

As it turns out, there are three start-up firms, all with significant funding and impressive scientific talent, currently at the prototype stage (more or less.)

It’s rather more hopeful than one might have thought–though the problem of scale is daunting, to say the least. (Vide “Langley + flight” for one cautionary example–and even if ‘technological scaling’ isn’t too problematic, solving CO2 via air capture would necessitate basically the creation of a whole new infrastructure–parallel at first, then taking over.)

http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/tag/kilimanjaro-energy/

Jim Bullis said: “Renewables as a source of electricity do not even figure in the equation since they are not remotely close to being in a position to handle load variations such as would be involved with electric vehicles.”

This was partially addressed by Jon Kirwan in #85, where he made the point that electric cars can, in principle, have a stabilizing effect on the grid. I’d add that IIRC (and I’m pretty sure I do, in this case) the Danes are experimenting with this as one way of increasing the utility of their wind generation fleet. (No pun intended.)

But what really puzzles me is this: Jim Bullis, weren’t you one of the very people making this “stabilization” argument two or three years back, here on RC? Wasn’t that an advantage of miastrada? Did I dream that, or what?

How about we start by switching all subsidies from fossil fuels to renewables. That would be a start, and fossil fuels has plenty of money without it. As to Solyndragatepocalypse, I saw Fiore commented earlier, and this is both funny and enlightening on the subject.

http://www.markfiore.com/political-cartoons/watch-solyndra-solar-green-tech-obama-stimulus-environment-animated-video-mark-fiore-animation

Huge jump in emissions is new front page news, and I see the MSM is beginning to let up on the hedging about GW/CC. (global warming/climate change – now I see why the new addition to alphabet soup).

Keystone XL is so obviously egregious on so many fronts (company record on spills is appalling) that it seems like mountaintop mining to be a good place to take a stand.

Big Carbon marches on:

http://thinkprogress.org/romm/2011/11/03/361158/biggest-jump-ever-in-global-warming-pollution-in-2010-chinese-co2-emissions-now-exceed-uss-by-50/

Tar Sands Action

http://www.tarsandsaction.org/

had better be just the beginning of the uprise of the humans.

#91–Just so, and well-stated, too!

I see a couple of comments have now pointed to this story in various forms, but just so I don’t completely appear to be a “cock-eyed optimist”:

http://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/story/2011/11/03/carbon-dioxide-atmosphere.html

Deep trouble. . .

The central point of Ray’s great article is that we already know how to economically recover far too much carbon.

We as humans are faced with having to voluntarily say “no” to a gigantic amount of economic carbon energy if we want to avoid thousands of years of extreme weather.

The wealthiest corporations in the history of money are set up in their very nature to oppose leaving any of that economic carbon in the ground.

So far we are failing miserably. The boulder is rolling with huge momentum. It is going to take a fight at every level, from both supply and demand and retail politics and social pressures to slow this beast.

McKibben has been on the front lines of trying to get citizens involved in this fight for a long time. And to his great credit he has figured out a number of ways to engage people around the world to step up and take on some part of the problem in larger numbers than I see almost anywhere else. The focus on Keystone XL is brilliant because it engages thousands in direct action, educates millions more and forces a dialogue with industry and politicians about one of the biggest carbon deposits on earth.

Those folks who think something else should be a focus should go out and do it. It will take all of it and more.