Eric Steig & Ray Pierrehumbert

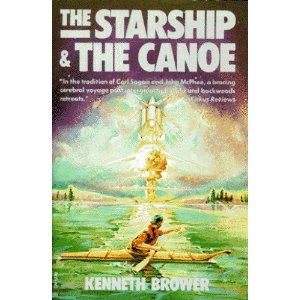

One of my (Eric’s) favorite old books is The Starship and the Canoe by Kenneth Brower It’s a 1970s book about a father (Freeman Dyson, theoretical physicist living in Princeton) and son (George Dyson, hippy kayaker living 90 ft up in a fir tree in British Columbia) that couldn’t be more different, yet are strikingly similar in their originality and brilliance. I started out my career heading into astrophysics, and I’m also an avid sea kayaker and I grew up with the B.C. rainforest out my back door. So I think I have a sense of what drives these guys. Yet I’ve never understood how Freeman Dyson became such a climate contrarian and advocate for off-the-wall biogeoengineering solutions like carbon-eating trees, something we’ve written about before.

One of my (Eric’s) favorite old books is The Starship and the Canoe by Kenneth Brower It’s a 1970s book about a father (Freeman Dyson, theoretical physicist living in Princeton) and son (George Dyson, hippy kayaker living 90 ft up in a fir tree in British Columbia) that couldn’t be more different, yet are strikingly similar in their originality and brilliance. I started out my career heading into astrophysics, and I’m also an avid sea kayaker and I grew up with the B.C. rainforest out my back door. So I think I have a sense of what drives these guys. Yet I’ve never understood how Freeman Dyson became such a climate contrarian and advocate for off-the-wall biogeoengineering solutions like carbon-eating trees, something we’ve written about before.

It turns out that Brower has wondered the same thing, and in a recent article in The Atlantic, he speculates on the answer. “How could someone as smart as Freeman Dyson,” writes Brower, “be so wrong about climate change and other environmental concerns..?”

Brower goes through a number of possible explanations for the Dyson paradox, some easily dismissed (senility; he’s a theoretician with no sense of practicality) some not so easily dismissed (he’s only joking, don’t take it seriously, he doesn’t take it all that seriously himself). But in the end, for Brower, it seems to come down to two conspiring things about Dyson. The first is that Dyson has an abiding faith in the ability of technology to do anything we want it to. It’s not surprising, then, that Dyson thinks we can ‘fix climate’ as well. That, in itself, makes Dyson not so much a “global warming skeptic” as an extreme techno-optimist. In fact, even leaving technology aside, he has a touching faith that whatever humans may do to the environment, it usually turns out for the best. In this essay, he writes:

“The natural ecology of England was uninterrupted and rather boring forest. Humans replaced the forest with an artificial landscape of grassland and moorland, fields and farms, with a much richer variety of plant and animal species. Quite recently, only about a thousand years ago, we introduced rabbits, a non-native species which had a profound effect on the ecology. Rabbits opened glades in the forest where flowering plants now flourish.”

We daresay that the Australians have a somewhat less benign view of rabbits (as the New Zealanders do of possums). And that maybe Dyson has a thing or two to learn about the biodiversity of unmanaged ecosystems.

Second, Dyson’s obsession has always been the stars, not the earth: he spent many years working on the design of a spaceship (hence the title of Brower’s 30-year old book) that would take him there. It’s not so much that he doesn’t care about our home planet — he must have learned something about ‘spaceship earth’ from son George over the years. Rather, he is simply very confident that we can always get off if we have to. “What the secular faith of Dysonism offers,” Brower writes” is, first, a hypertrophied version of the technological fix, and second, the fantasy that, should the fix fail, we have someplace else to go.” Dyson has stated in many places, and in various ways, that he thinks global warming is not a big problem, and that its importance has been exaggerated. To put things in perspective, though, Dyson doesn’t particularly think that the extirpation of all life other than human would be a particularly big deal “We are moving rapidly into the post-Darwinian era, when species other than our own will no longer exist, and the rules of Open Source sharing will be extended from the exchange of software to the exchange of genes,” he is quoted as saying in Brower’s article. Dyson’s idea of what constitutes a “big problem” may be, well, just a bit different from what most of the rest of us might have in mind.

Brower’s conclusions sound right on the mark to us, but don’t fully explain Dyson. Perhaps Brower is being gentle, since he is an old friend, or perhaps he simply isn’t aware of it, but one issue he does not touch on in his article is is how deceptive (apparently deliberately) Dyson can be.

The problem is that Dyson says demonstrably wrong things about global warming, and doesn’t seem to care so long as they support his notion of human destiny. Brower reports that Dyson doesn’t consider himself an expert on climate change, has no interest in arguing the details with experts, and yet somehow knows that the experts don’t have any answers worth listening to. That doesn’t stop Dyson from making sweeping pronouncements, many of them so egregiously wrong that it would hardly have taken an expert to set him straight.

The examples of this are legion. In the essay “Heretical thoughts about science and society” (excerpted here) Dyson says that CO2 only acts to make cold places (like the arctic) warmer and doesn’t make hot places hotter, because only cold places are dry enough for CO2 to compete with water vapor opacity. But in jumping to this conclusion, he has neglected to take into account that even in the hot tropics, the air aloft is cold and dry, so CO2 nonetheless exerts a potent warming effect there. Dyson has fallen into the same saturation fallacy that bedeviled Ångström a century earlier.

And then there are those carbon-eating trees. He likes this one so much he put it in both the Heresy essay and in his piece in NY Review of Books. He points out that the annual fossil fuel emissions of carbon correspond to a hundredth of an inch of extra biomass per year over half the Earth’s surface, and suggests that it shouldn’t be hard to tweak the biosphere in such a way as to sequester all the fossil fuel carbon we want to in this way. Dyson could well ask himself why we don’t have kilometers-thick layers of organic carbon right now at the surface, resulting from a few billion years of outgassing of volcanic CO2. The answer is that bacteria have had about two billion years to evolve so as to get very, very good at combining any available organic carbon with oxygen. It is in fact extremely hard to put organic carbon in a form or place where it doesn’t get oxidized back into CO2 (Mother Nature thought she had done that trick with fossil fuels but we sure fooled her!) And if you did somehow coopt ten to twenty percent of the worldwide biosphere’s photosynthetic capacity to take up carbon and turn it into a form that couldn’t rot ever, you’d have to sort of worry about how nutrients would ever get back into the ecosystem. And also maybe whether the carbon-eating trees might get out of control and suck out so much CO2 you wound up in a Snowball Earth.

Dyson espouses a generic disdain for climate models and climate modellers: ” Here I am opposing the holy brotherhood of climate model experts and the crowd of deluded citizens who believe the numbers predicted by the computer models.” Like most of us, he has little confidence in the modelling of clouds. But with great ignorance of the nature of the modelling enterprise, he declares: “It is much easier for a scientist to sit in an air-conditioned building and run computer models, than to put on winter clothes and measure what is really happening outside in the swamps and the clouds” Actually, those of us who go to Antarctica to drill ice cores certainly put on winter clothes, and paleoclimatologists are out in the swamps and ocean muck all the time. And there are plenty of scientists flying around in the clouds, trying to gauge their effects. The mainstream estimate that the climate sensitivity is around 3°C for a doubling of CO2 does not simply comes from computer models. Study of the Last Glacial Maximum, the Pliocene and the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum all rule out the idea that there is a strongly stabilizing cloud feedback. Ahe fact that we cannot precisely quantify cloud feedbacks also means that there is a lot of risk, that cloud feedbacks could make a doubled-CO2 world much hotter, not much cooler. Dyson’s writings conveniently ignore this two-directional implication of uncertainty, and they they also ignore the implications of the long atmospheric lifetime of CO2, which means if we wait and see how hot it gets and find we don’t like it, there’s nothing much to be done (unless, of course, we can simply go somewhere else).

Finally, there is the familiar examples of Dyson attacking the style of the debate, rather than its substance. Reporting on written debate between Richard Lindzen and Stefan Rahmstorf, in the New York Review of Books New York Times book review, Dyson juxtaposes Lindzen’s claim that “observations suggest that the sensitivity of the real climate is much less than that found in computer models” with Stefan calling this “simply ludicrous”. Dyson gives the impression that rational arguments from skeptics are met with “open contempt” by the majority. But he fails to mention that Stefan showed in detail why Lindzen’s claim is wrong: Lindzen ignored ocean thermal inertia when comparing observed warming with the equilibrium climate sensitivity. Any physicist should be able to judge that Stefan is right and Lindzen is wrong on this point. He also failed to mention that Stefan used the word “ludicrous” only in a “personal postscript” to a completely sober scientific article, referring to Lindzen’s claims that a vast conspiracy of thousands of climatologists worldwide is misleading the public for personal gain. Dyson’s account of the Lindzen-Rahmstorf exchange neither fairly covers the substance of the argument, nor is it a fair portrayal of its style – Dyson seems to have twisted it as much as he could to score a political point.

In the Heresy essay, Dyson repeatedly gives himself a way out by claiming he is only tossing out ideas that should be thought about; he at times emphasizes that he does not know the answers, only the questions that should be raised. However, that does not stop him from making confident claims that he has a broader view than others, as in this interview with Mike Lemonick, and somehow Dyson never gets around to thinking about what the consequences are if we continue inaction on CO2 emissions and he turns out to be wrong. More importantly, all of the things Dyson argues “heretically” should be looked at — e.g. land carbon sequestration or the lessons from the Altithermal period around 8000 years ago — are in fact already being intensively investigated and are not turning up any silver bullets to allay concern about climate change. When push comes to shove, Dyson is really only offering warmed-over standard contrarian talking points. Heresy, or more broadly an outsider’s viewpoint, can be a good thing when it shakes loose new ideas. But surely, we have a right to expect a more original form of heresy from the architect of Dyson spheres and nuclear starships.

In short, it’s not so simple as the ‘self delusion’ Brower talks about. Dyson is not doing science, but he is deluding others under the guise of science. Given’s Dyson’s evident love of science (and expertise in it), that’s the part that we still don’t get.

Dyson’s hypothesis (that limitless technological inginuity can overcome any obstacle) actually leads to the paradoxal conclusion that we should be very, very careful with what we do on and with this planet.

I’d like to designate this reasoning as the “Dyson Paradox”, and it goes like this :

If human technological ingenuity will eventually enable interstellar travel and build Dyson spheres (or the more practicle Dyson ‘swarm’s) around our sun and nearby stars, then one small step beyond that we would transform and colonise the entire Galaxy, and this would surely be observable.

Since we still see stars at night, and no alien species has (in the past) crunched up our planets and turned them into space habitats, so other species has apparently succeeded in colonizing the entire Galaxy before us. So either the lifetime of all technological civilisations in this Galaxy is limited and technology dies out at some point, or we are an extremely unique in the Galaxy.

If we have limited lifetime, then technological ingenuity apparently has hard upper limits, or technology itself causes civilisations like our to end. And if we are extremely unique in the Galaxy, then, being the only intelligent lifeform in the Galaxy should give us some real prespective on how precious life really is.

Either way, it seems that should be very, very careful with our planet and all it’s life splendor and diversity of species.

And that conclusion is opposite from the hypothesis that we started with. Thus Dyson’s belief is either emperically disproven or it leads to a paradox. Dyson’s paradox.

Lesson learned from the stars : Earth is all we have and likely all we ever will have. Be careful with her.

Rob, your “Dyson’s Paradox” is a restatement of Fermi’s Paradox. And in any case, Dyson’s vision is basically a hallucination. He ignores the fact that we would be bombarded by a constant flux of about 6 cosmic ray particles per square cm per second. These cannot be practically shielded and over a period of months to years would kill us.

Dyson has a talent for ignoring details.

Leonard Weinstein: “The third possibility is that Dyson is correct.”

The Fermi Paradox says otherwise.

Ken, indeed. I have sometimes proposed this for bringing OTEC generated energy from the tropical oceans to consumers.

You have to consider of course that the main selling point of space based solar is that you’re in sunlight 24/7. On the Earth surface, not so. Whether that’s enough of a selling point, given the cost of putting stuff in orbit, is a legitimate point of discussion.

“… CO2 extraction from the air may seem like a small engineering problem in comparison.”

Of course, the engineering is a snap. Paying for it is the problem. There Dyson isn’t faced with Man controlling Nature. There we’re faced with Man v Man.

Hand waving and pontificating don’t work.

Ken Fabos at #148 graphically points out a sobering reality that I haven’t seen pointed out much elsewhere: yes, if we are unable to survive here together on our basically friendly planet, we certainly won’t manage to survive in space settlements, where the skill set required is pretty much the same, only much more so.

I am reminded of a story by Asimov (?):

Q: it rains and you’re sheltering under a tree. The rain goes on and on and the tree starts leaking through. What do you do?

A: Find another, still unused tree.

Fred Hoyle spent his later years being very successful at diminishing

my respect for him. So when I read a commentary on Hoyle by Dyson, I

expected, if not condemnation, at least some evidence that Dyson had

standards. I was disappointed: Dyson gave Hoyle a free pass. I assumed

at the time that he did it because they were friends. However, now that

my respect for Dyson is going down, I see some sort of pattern.

Fun fact / Trivia

Spaceship Earth (1982)

A dark ride in EPCOT that takes you through the amazing story of human

communication. From the prehistoric times and the development of language to present

day and future technology this ride accompanied by a wonderful score by Edo Guidotti

that will truly make you feel at the happiest place on Earth..

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0111251/

Survival of Spaceship Earth (1972)

Earth’s environmental crisis–brought about by uncontrolled technological

progress–is endangering life on a global scale. At the core of the threats to the

planet – wars, overpopulation, pollution, and the depletion of natural resources –

is the inadequacy of the nation state to come to terms with the surmounting problems

of twentieth century living. What is urgently needed is the kind of international

cooperation where nation states relinquish part of their sovereignty to a world body

entrusted with the management of mankind’s future.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0278756/

Jim Dukelow #150: precisely what don’t you know? There is pertinent info here

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space-based_solar_power

and links therein. Basically you are using a rectenna with a power density in the centre of 23 mw/cm^2 in the middle, 10 mW/cm^2 at the edge, and considerably less outside the beam. These intensities have been tested on animals without obvious bad effects. Humans wouldn’t be affected at all, because they would be inside aircraft (if these would be allowed to fly through the beam; unlikely).

(rules for allowable exposure are a bit of a jungle… I found this

http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/cfr_2004/octqtr/47cfr1.1310.htm

where Table 1B seems to say that at 2.45 GHz, 1.0 mW/cm^2 is acceptable for the general population, meaning the rectenna would have to be in a somewhat remote location with nobody living nearby.)

About the local climatic effects, they would be considerably less than those of an equivalent conventional power plant, as the conversion efficiency is around 85% as against 40% or so for conventional. The effect on the ionosphere could be potentially more serious and has not been studied much to my knowledge.

Here is my attempt at the pressure in a rotating Dyson sphere problem. The acceleration g is cylindrically symmetric, varying linearly as the distance from the axis of rotation, r*cos(theta), and the potential therefore goes as (r*cos(theta))^2

taking R to be the radius of the sphere, and h to be the radial altitude (R-r)

i eventually get an exponential atmosphere that goes as

constant*exp[(h*cos(theta))^2-(R*sin(theta))^2], the constant being an exponential in the square of the angular frequency of rotation of the sphere, divided by the temperature with the usual mass and Boltzman constants

Jim Dukelow (#150):

The idea of collecting solar power in space and transmitting as microwave to the earth is studied as a down-to-earth technology (not a Dysonian dream) in Japan, e.g. [A web page in JAXA], [A web page in Kyoto University]. I heard that they study such questions about the cost and safety as you raised, and that they design to have an optimum energy flux density high enough to be useful and low enough to be harmless. But I have not got yet details.

114, SecularAnimist:What Einstein objected to was the idea that concepts like indeterminacy, uncertainty, nonlocality and complementarity were not just aspects of the abstract models but of physical reality itself.

You might be right.

It depends on the degree to which the “model” is presented as “the reality”, or the epistemology as the metaphysics (or ontology), in the presentations of the science. That is a very short sentence for a complex dependency; please forgive me. But even Newton’s first law is ambiguous in this regard: no object moving uniformly in the absence of external force has ever been observed, but the law is for sure a part of an excellent model. So to take the model (which is excellent) as the reality (despite the absence of an object in uniform motion having ever been observed) requires a leap of faith.

I don’t think Einstein was successful at persuading the scientific community that what he meant was what you wrote on his behalf. I think that modern readers mostly consider his work on the subject (such as the EPR paper) either hopelessly obscure or demonstrably wrong.

I don’t really think he should be lumped with Dyson. Dyson is willfully wrong about some empirical facts which he could check.

Having read the entire thread to #154 I’ve picked out the most interesting (to me) comments and add some of my own:

“Extirpation can work many ways, and one of them is to wipe out the fruits of four billion years of natural selection and replace it with continents covered with hybridized gengineered corn and bananas.” I too fume at the kind of arrogant, calloused “so what!” attitude whenever I read about some hotel or parking lot being proposed on that which is home to a threatened or endangered species.

“Or perhaps because he [Dyson] treats the prospect of human suffering as a phenomena to be observed in the context of the grand sweep of history, rather than something to try and prevent”. Mengele had the same cold philosophy. The end justifies the means (just so long as I’M not one of those made to suffer).

“It often makes me wonder if we’re not confused, if there aren’t two intermingled but separate species of sapient beings on this planet, both of which look identical, even to an extreme similarity in DNA, but which simply have to be different species. There must be some obscure, brief genetic sequence that distinguishes homo sapiens from homo scurra.” I’ve often wondered the same thing. Maybe we are an extension of the strange differences between regular thuggish chimpanzees and the bonobos…

“The chances of colonists surviving long term off earth are nil.” Yep. The technologists, though, like to come back and say “hey, people used to say that man would never fly or travel to the moon but we did” as a way to squelch dissent from the all powerful techno fix.

“It would set us Free of the Earth”. “Free”, if you consider earth to be a prison. What the technological cornucopians willfully fail to realize is the very high level of our dependence upon this planet that we have co-evolved with. We-ARE-the-earth and all it’s species. We are so adapted to it that denied any one of many precise qualities for long and we would begin to suffer and die. Are we going to terraform another planet that thoroughly anytime in the near or even distant future? Highly doubtful. Would anyone really want to trade life on earth for the prison of a Dyson sphere or ringworld?

“The real world of our future is totally dependent on the level of greed of a continually expanding human population exploiting continually declining material resources.” Yep. “To reverse it, I do not believe that any of our global political systems have the capability. External events will be the drivers.” It’s looking that way.

“I should state that I have a great deal of hope for a biotech solution to mop-up carbon dioxide.” I certainly do not. So far all it’s been about is lots of glowing promises, an ever expanding class of super weeds and suicides (in India), and money in the bank for the likes of Monsanto.

“If you average together Dyson and Lovelock, their foibles and craziness will cancel out.” Not by my reckoning. Lovelock say that the earth behaves like a single organism, something that his protege, the respected Lynn Margulis also says. I happen to wonder if the earth may have also evolved a “world mind”. That’s just speculation though.

Comments by Michael K — 9 Feb 2011 @ 1:39 PM. Right. People do tend to get full of themselves, and protective of their “legacy” when that legacy has achieved them adulation. And no one does cheap adulation like the funders of professional skeptics, whether that’s in the field of climate change or creationism.

“(Though geo-engineering seems particularly prone to the grandiose.)” It sure does. It’s like a big game to those who would play around with systems which have co-evolved to a nice working balance.

Comments by Ken Fabos — 11 Feb 2011 @ 4:44 PM. Exactly. I read a sci-fi book once called Voice of the Planet that, if I remember right drew this idea out.

Comments by Kevin McKinney — 11 Feb 2011 @ 9:15 PM. Right.

Comments by Ken Fabos — 11 Feb 2011 @ 11:49 PM. “Anyone imagining that there would be less regulation and more individual freedom within a space habitat is seriously kidding themselves”. That’s one thing you can count on. Any habitat with smaller dimensions and less fragile than the earth will have much more regulation.

“Designing credible, believable castles in the air is a skill. Living in them — isn’t something to count on.” I think we would discover that pretty quickly.

“Either way, it seems that should be very, very careful with our planet and all it’s life splendor and diversity of species…. Lesson learned from the stars : Earth is all we have and likely all we ever will have. Be careful with her.” Well and wisely said.

Dyson is actually his own nemesis. By trying to protect the dirty energy industry he is saying that he doesn’t think that we CAN build a better world technologically than that which is based on fossil fuels. And I thought he was supposed to be the optimist.

On second thought maybe he knows we can, it’s just that he’s getting something out of things staying the same. Hmmm.

Thanks RC for catching my comments. I thought I’d lost them with the captcha issue. Sorry for the multiple posts.

Here’s something else to mull over for those wondering what makes the Dysons tick. Anybody with children will tell you how hazardous it is to try to make any judgment about the parents from what the children are like, but since Brower brought up the interesting Freeman/George dynamic, it is interesting to look at how BOTH Dyson kids in some way simulataneously fell near to and far from the tree. Apropos of that, everybody likes to talk about George, because he lived in a tree and now builds kayaks, but how come we hear so little about Esther? In my view, she may be the most interesting (and almost certainly the most influential) Dyson at all. Check out her activities at http://www.edventure.com/ . And don’t let the name of the site fool you into thinking she does something like arranging kayak adventures.

I’d like to add one more thing; something that perhaps would be evident to evolutionary biologists. The only way we could survive in space or on another planet for long would be to become something other than homo sapiens, so intimately are we physiologically and psychologically connected to this planet. And since the natural process of evolution would be too slow and clumsy in the short term we would have to be engineered in labs to adapt

What then would we be?

#166–

. . .not that there’s anything wrong with kayak adventures, of course!

Thanks for the pointer!

167 Ron R said, “The only way we could survive in space or on another planet for long would be to become something other than homo sapiens, so intimately are we physiologically and psychologically connected to this planet.”

I disagree. A space ark or station would have to be huge in order to incorporate enough shielding to protect enough people to make it worthwhile. Only desirable species would exist and the weather would be perfect, making it easy for people to do what people do, which is adapt to the circumstances.

> Only desirable species would exist

Oy.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMe020092

I believe the physicist Murray Gell-Mann (elementary particles, Nobel Prize) once remarked that there is a variety of British physicist that would rather be “clever” than right.

Maybe Dyson has a touch of this.

Richard C., It would take 13 cm of aluminum to sheild out half of the galactic cosmic rays. I’d LOVE to see the rocket that launches that bird!

Keep in mind also that all materials eventually degrade in a radiation environment. Also keep in mind the bone loss that occurs in low-gravity environments. Star Trek is science FICTION for a reason.

From an evolutionary perspective, we absolutely have to eventually get off this planet and colonize other worlds. Otherwise, in the long term, we are extinct with 100% probability, and not going extinct seems to be the only purpose of out existence.

That, of course, does not mean that it is possible to do so; right now, it looks like it isn’t, but if it is, for all the reasons listed above and many others, it will require knowledge and mastery of the laws of physics and technologies derived from such understanding that are unimaginable right now. We are very far off from such level, and, again, we will likely never reach it as may simply not exist.

But we have to try, and in order to do that, we need time and resources. We are never going to have those if the current civilization collapses, because whatever fraction of humanity survives, will have to live in a ruined world (that may even become completely uninhabitable, depending on how stupid our behavior is in the next decades) with depleted resources and most of the knowledge we have accumulated during the last few centuries gone. And because the resources that allow humans to build the kind of civilizations that build particle accelerators will have been exhausted/dissipated into the environment, that knowledge will never be regenerated, cutting whatever chances we had of leaving the planet.

So the only sane strategy is drastically and urgently reducing the environmental impact and resource consumption to a level that does not make the scenario described above an inevitability, and investing everything into research, with the full realization that that research may take many centuries or even millenia and may never succeed.

The techno-optimists and techno-fixers seem to drastically underestimate all three basic components of the situation – the physical possibility of the proposed technofixes (no amount of ingenuity can get you around the Second law), the amount of effort it will take to make them happen when they are realistically possible, and the speed at which we’re driving towards the cliff. Why extremely smart highly educated people fail to appreciate any of that is a mystery indeed

That nails it quite well. However, it also reminds me how superficial the discussion about AGW usually is, even when coming from people on the correct side of the fence. AGW is only one part of our global sustainability crisis, with resource depletion (fossil fuels, phosphorus, other minerals and metal ores, fossil aquifers, topsoil, etc.) and ecosystem collapse being just as serious, and all of them being very closely interconnected with each other. So we have to look at the whole picture, not just at one of those problems, and while AGW is a very serious problem on its own, it is actually counterproductive to focus exclusively on it, as “solutions” targeted at only one aspect of the crisis often aren’t really solutions at all when the whole is considered. And the whole picture is much much scarier than even the direst climate change scenarios for the future on their own.

But even then, we would be missing a very essential piece of the puzzle which is our view of our own place in the world, which is the root of our inability to do anything about all of those things listed above. And that has very deep cultural and religious roots, and those are too sacred cows for the vast majority of people to touch on. Until we stop seeing ourselves as “special” and appreciate what our place in the world is and how fragile our existence really is, we have absolutely no chance of adequately addressing those issues. I know that people don’t like to discuss it, but the “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth” sentence is what is at the root of the conservative’s opposition to AGW. And that applies to the thinking of many people who aren’t even religious, simply because our culture is so deeply permeated with that attitude. Now given what the response from the religious fanatics and right wing is to even the feeblest of proposals for AGW legislation and how any adequate measures to prevent global societal collapse are going to be orders of magnitude more drastic, there is absolutely no hope of ever making that happen unless those sociocultural attitudes are thoroughly eradicated. Which is a simply impossible task given how little time there is, but is made even more impossible by the fact that so few people dare to talk about it…

Georgi Marinov 13 Feb 2011 at 12:11 PM, nice post.

Ray Ladbury: “It would take 13 cm of aluminum to sheild out half of the galactic cosmic rays. I’d LOVE to see the rocket that launches that bird!”

And think of the natural resources it would take to just to build a sizable Dyson Prison, er, Sphere (I prefer living in open systems to closed ones myself).

I am not against space travel at all. I do hope that we find a way to travel to the stars, or at least to the other planets in our solar system. I’d love to visit them myself if I could. I just have real doubts about long term space travel and it’s effects on us. Maybe this is our future…

http://www.hyper.net/ufo/pics/alien.jpg

I also happen to think (silly me) that it’s, well, kind of crazy to write the earth off when it’s clearly all we have and if simply taken care of it is so well suited to life. Our first priority ought to be earth’s preservation (why does this obvious fact even need defending? Why am I embarrassed to mention it? Why has the idea of conservation changed from a virtue to a vice in the minds of so many?). Anyway, after securing a future for our home planet we can go to the stars. But it simply should not be an either/or situation.

Let’s get our heads out of the sand and tackle overpopulation, resource depletion, habitat destruction, species extinction, air/water/ground pollution and climate change head on. It’s unfortunate that to date no one in any real official capacity seems to even want to talk about these issues (which by itself would go a long way toward fixing things, kind of like an alcoholic admitting he/she actually has a problem), fearing the tea party like backlash of the corporatists and capitalists.

And so we march on like lemmings toward the cliff.

Ron R.@163 says “Lovelock say that the earth behaves like a single organism, something that his protege, the respected Lynn Margulis also says.”

Respected or not, Margulis is hardly the ideal referee when it comes to judging the scientific sanity of a position – some of her opinions are also pretty much ‘out there’…

RE # 173

Georgi, you said, “From an evolutionary perspective, we absolutely have to eventually get off this planet and colonize other worlds. Otherwise, in the long term, we are extinct with 100% probability, and not going extinct seems to be the only purpose of out existence.”

Matthew said:

Matthew 19:30 But many who are first will be last, and many who are last will be first.

Where are you, in the line. Would you let the poorest get to the head of the line? Or, only the richest?

Anyway, it is a part of the absurdity of human nature to think we will ever leave this planet except in our dreams. Get back to work.

John McCormick

I don’t see what what I said has to do with who’s rich and who’s poor? I was talking about the species.

I think I clearly stated that space travel Star Trek-style is most likely a physical impossibility. But we are not sure that it is impossible, and that we are obliged to at least try. That means research and lots of it, for which to happen we must absolutely not collapse now because there will be no second chance.

I have had this debate numerous times with various people and for some mysterious to me reason it very often devolves into accusations of elitist bias, putting the rich in front of the poor in the line, etc., even racism, things that are completely irrelevant to the discussion and that simply can not be part of any society that follows from the lines of thought I present anyway. That can only mean that people simply don’t get it all even when you say it as directly as possible.

Which is very sad and discouraging…

Gerry Quinn, no doubt there is controversy (what else is new?) and she may be a bit of a scientific maverick (her cooperation vs the traditional competition only ideas as movers in evolution; e.g. plants trade genetic material rather freely).

While I don’t really want to get into a debate about her personally, I think you are being a bit too hard on her. She’s no Velikovsky.

http://www.geo.umass.edu/faculty/margulis/

A much more compelling statement before July 16, 1969.

Interesting thread, with books, bunnies and boats. While I enjoyed the Starship and the Canoe, I’d go nuts in space. Why has no one pointed out how nice kayaks are? My wife and I had a lovely sea kayaking day last weekend here in Trinidad, West Indies. For most environmental scientists, likely preferable to living in a starship. Perhaps Freeman should get out more. But then he would see our increasing temperatures, extreme weather events, acidifying ocean and dying coral, decreasing biodiversity, and the nasty bits of floating oil and garbage we have to paddle the kayak around. Bummer.

I am a psychologist (motivation and personality is my field), and while I have hardly done an in depth study of Freeman Dyson, I can offer a few other inputs. I agree that being a fan of technology is a contributing factor; he also likes big, sweeping human actions. But fundamentally I suspect a key driver is his obviously quite strong influence motive. (The literature refers to it — overly negatively — as Power motive.) Dyson is clearly driven by the desire to have an impact on or influence on others — hence his highly public statements and numerous books, some of which are clearly for the general public rather than colleagues. (Cf. David McClelland, if you want to know more about the Three Social Motives; Dyson also shows signs of significant Achievement motive.) I found in my own research that published writers in the popular realm tended to be quite strong in this nonconscious, emotional drive (See my book on writing). These days, you can join the vast numbers of people supporting AGW and join in the research, much of which appears from the outside to be incrementalist and collective rather than dramatic and individualistic, or you can be a contrarian and make a splash and get lots of visibility with no work at all. Please note that I have no brief for this view; I think excitement is wherever you find it. I think Dyson, however, may feel this way: no room for big, exciting experiments or theories where you have to blow something up or do something cosmic to fix the problem — just careful, calculated actions that must be kept in check lest we tilt the balance the wrong way.

And hey, he’s in his eighties. I doubt he really cares to do the serious reading it would take to have an informed opinion. The sad thing is that he probably knows this and doesn’t admit it or want to take a more nuanced view.

I admit to getting a thrill from the idea of colonising space but I think the reality is going to be uncomfortable and confining as well as very difficult, extremely expensive and facing some serious problems with sustainability; the lessons needed to be learned are probably the ones we face right now here on Earth. And as others have pointed out, failure here over the next few decades will leave us unable to engage in such an exercise into the future.

We currently have economies that can support complex research and development, a population that produces brilliant thinkers and innovators in significant numbers and the social and educational opportunities that means many of them can flourish. There may be lower limits for populations, economic size and resilience and minimum diversity of skills and opportunities that space habitats will struggle to reach or maintain; they may be able to retain a vast amount of stored knowledge and may begin with a good number of the brightest and best but they may risk longer term stasis or decay without something like a global economy underpinning them. Smaller, more easily regulated populations with a strong sense of their vulnerability may avoid some of the disunity and disputation over doing the minimum that’s necessary but there will be costs to longer term viability.

For the next few hundred thousand years when faced with possible human extinction I also suspect that the advantages of space habitats over Dr Strangelove style bunkers could also be debatable.

Isn’t it better to take our existing biosphere’s sustainability much more seriously and at least make an all out effort to avoid permanently messing up what is still, even now, by far the best real estate around?

#183–

My, Ken, how you persist in saying sensible things!

These considerations may not be the last word, but IMO they are definitely worth pondering, if we take the subject seriously.

Not that there aren’t already enough good reasons to take sustainability seriously.

It is not an either/or question and that’s not the argument – the argument is that we have to do absolutely everything possible not to destroy the Earth so that we have some non-zero chance to leave it by the time it becomes uninhabitable for us for natural reasons.

Values are not to be found in outer space but inner space. The mess we find ourselves in is a question of values, not technology nor science. Neither technology nor the physical sciences can tell us anything meaningful about values (Heisenberg, Schroedinger, Einstein, De Broglie, Jeans, Planck, Pauli and Eddington all understood this and none had a materialistic worldview.) The evidence all around us, however, is that science and technology is being, and has been, used by the few to exploit the planet’s limited resources for self-centered material gain and power (i.e. economic development) with scant regard for human development. The value drivers for this behavior? Anger, greed, stupidity, desire, jealousy and pride. The antidote is practices that lead to discovering the wisdom and compassion (and capacity for genuine happiness)inherent in all of us.

Actually I think that’s a misguided way of looking at things. Physical sciences can and do tell us a lot about values – they tell us that values are an artificial human construct that has absolutely no meaning in the real world, where what matters is whether you survive or not. The drivers of our behavior are the same evolutionary factors that drive the behavior of most other organisms on this planet – the urge to maximize one’s reproductive success is the major one and it is the direct cause of all the greed, jealousy, etc. you mention.

The reason it is counterproductive to think in terms of those things you mentioned and not in terms of basic biobehavioral terms is that they move the conversation into a completely different plane that pushes us towards different (and invariably inadequate) “solutions” to the problems. All utopian social systems that have been proposed and tried in practice have failed and that was usually because they were designed around a rosy picture of human nature that had little to do with reality.

[Response: There’s a whole bunch of things wrong with your arguments here frankly. The idea that the physical sciences “tell us that values are an artificial human construct that has [sic] absolutely no meaning in the real world” is utter nonsense. Values of all kinds have a definite and strong biological basis. Secondly, your view of human nature is distressingly bleak and offers really no hope for anything except constant warfare. Thirdly, Hugh was not talking about building any “utopian social systems”–big straw man there on your part. He was simply mentioning some basic changes in human attitudes that are open to everyone. Fourth, most human societies are way beyond the “red in tooth and claw” survival mode you discuss. Human nature and human society are just a tad more complex than you seem to recognize–Jim]

#187 Georgi

“values are an artificial human construct” True. There’s nothing either good or bad but thinking makes is so – Shakespeare”

Science is also a “human construct”

“Your” whole reality is “constructed” (i.e. interpreted and given meaning) in “your” mind.

“Your” response is a “human construct”.

“All utopian social systems that have been proposed and tried in practice have failed and that was usually because they were designed around a rosy picture of human nature that had little to do with reality.”

Examples? But I agree that utopia is impossible – it presupposes common values of what constitutes utopia and the conditions that satisfy such common values.

“where what matters is whether you survive or not” Why does survival matter to you? Why do you value survival above all else (this is what you are implying)? This is the lowest level of Maslow’s heirarchy of needs. The fact that you posted a response to my post logically contradicts that statement of yours. Do you not also want some sort of recognition (social esteem need) for your ideas (ideas – human constructs, and hence your post?

Suggested reading “Quantum Questions” ed Ken Wilber; the mystical writings of the world’s greatest Physicists (the list given in my original post). They understood the limitations of science. Biophysical reality is defined as that which can be measured (using SI units of measurement – agreed upon by convention). You, the measurer (consciousness), exclude yourself from that biophysical reality and it is within your consciousness that a model/image/idea of that reality is constructed. This is true for all our experiences.

All I wanted to point out is that the materialistic worldview is not supported by modern physics. In his essay “In defense of mysticism” Eddington wrote “It will perhaps be said that teh conclusion to be drawn from modern science is that religion first became possible for a reasonable scientific man about the year 1927. If we must consider that tiresome person, the constantly reasonable man, we point out that not merely religion but most ordinary aspects of life first became possible for him in that year. Certain common activities (e,g, falling in love) are, I fancy, still forbidden him. If our expectation should prove well founded that 1927 has seen the final overthrow of strict causality by Heisenberg, Rhor, Born and others, the year will certainly rank as one of the greatest epochs in the development of scientific philosophy. The [apparent conflict between science and religion]will not be averted unless both sides confine themselves to their proper domain, and a discussion which enables us to reach a better understanding as to the boundary should be a contribution towards a state of peace.”

In summary, and very simplistically; human actions are causing climate change; human actions are driven by human intentions; human intentions are directed by human values; it’s a value judgement to regard human caused climate change as “bad” or “good”; even the most base level (survival needs) of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, (a limited psychological model, but one that seems to have found favor in business courses on organisational behavior) says it’s bad; the present economic system is disconnected from biophysical reality and in essence is driven by the values of greed and fear (as will be readily admitted by those who speculate professionally on the stock market).

#186-188, including inline response–

My take would be that:

1) Values are a human construct, but

2) Human beings are NOT tabulae rasae (‘blank slates’) as posited by some philosophers, since

3) Human perception and cognition are built on biological foundations which significantly condition whatever ethical edifices we may construct for ourselves.

That would imply that human values are limited with respect to ‘artificiality’–as Georgi’s very next sentence implies:

Since reproductive success is said to drive human behavior, that’s clearly the operative value–and yet it’s shared with most of rest of the animate realm. NOT so ‘artificial!’

On the other hand, I’m not sure what Eddington et al. have to do with this portion of the argument. If our values–and, BTW, are “Anger, greed, stupidity, desire, jealousy and pride” listed by Hugh as ‘anti-values’ or what? I’m not too clear what the full implications of the term “value driver” are–if our values are a product of rationality based upon biology, then surely the question becomes one of harmonizing contradictions?

Thus, for example, the moralistic condemnation of greed may be more usefully reframed as an imperative to manage the desire for material security–which I take to be the value underlying the sin of greed–in such a way that it does not become self-defeating via a tragedy of the commons, or some (roughly) parallel mechanism. Basically, this line of thought brings us back to enlightened self-interest–though I’m not sure it needs to be *Enlightened* self interest, if you know what I mean.

The imperative to correctly price GHG emissions would presumably fall under this heading writ large: we want to enjoy the benefits of wealth, but not at the price of fouling our own nest irrevocably. So we create (or at least I sure hope we will) a mechanism that harmonizes/balances/mediates the two.

Ron R.@179

I didn’t say Margulis was a Velikovsky. However on at least one occasion she has endorsed and promoted research which is generally considered to be somewhat Velikovskian. (I refer to Donald Williamson’s proposal that butterflies arise from the hybridisation of insects and worms.)

Lovelock’s ideas, like everyone else’s, should in any case stand or fall on their own merits. I merely point out that endorsement by Lynn Margulis may not lend them quite the cachet her fame would suggest…

What you’re saying does not goes exactly against what I said – I said that “values”, in whatever way you define them, reside on a more superficial level than the purely biological drivers of behavior do, therefore it is more useful to focus on the biological part than on the sociological/ideological. That’s true whether values are derived from biological instincts or not, and I by no means agree that all of them they are

Human history for the most part consists of constant warfare, doesn’t it?

It’s not a straw man at all, I didn’t wrote that with the intention to rebut him as if he was having any utopia in mind, I just wanted to point out that the overtly rosy view of human nature can lead to disaster if people try to build social systems as if it was true. In fact, it is leading to disaster right as we speak.

Depends on what you mean by “beyond the “red in tooth and claw””. Violence (in time of official peace at least) has greatly decreased with the increase in societal complexity, that’s true. But that hasn’t happened as a result of some deep biological change, it has been all social and cultural factors – people were living in much more violent societies mere centuries ago.

But “red in tooth and claw” does not have to be understood only in terms of physical violence – it still drives our behavior even when we’re dressed in expensive suits in corporate boardrooms. Reproductive success in humans has a lot to do with status, so we seek to maximize it; and we also seek to obtain possession of as much resources as possible now in case there aren’t any available in the future. That’s where greed comes from, that’s where social inequality comes from, that’s where our self-destructive behavior comes from. Yes, society is very complex, human beings are very complex, and there are a great many other factors behind their behavior layered on top of the above, but that doesn’t mean that it is not true. All I am saying is that it does nobody any good to keep denying those unpleasant truths about ourselves. I am by no means advocating (and here’s where many people get it completely wrong when one opens this discussion) continuing or escalating that behavior just because it is what we do, I am pointing out that because it is something very maladaptive in the long run, we have to design our social systems so that it is restrained as much as possible, and the first prerequisite for this to happen is recognizing the existence of the problem.

> insects and worms

Well, not quite “worms” (fascinating digression, thank you).

A “velvet worm” isn’t a worm, like a “velvet ant” isn’t an ant.

SciAm laughed:

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=national-academy-as-national-enquirer

“Velvet worms, which fall between worms and insects on the tree of life, have soft-bodies and superficially resemble caterpillars, particularly the larvae of an early butterfly relative known as Micropterix. Velvet worms have evolved a variety of elaborate fertilization procedures….”

But the mechanism suggested is credible, given how they do transfer gametes. Ewww!

“… velvet worms are lost in a mysterious fog in terms of their exact place in phylogeny with respect to arthropods. Apparently worms with legs, Onychophora are an evolutionary nightmare. Treated for years as a missing link between annelids and arthropods, new research from 2006 reveals a closer association to the latter, particularly Chelicerates….”

http://harkerbio.blogspot.com/2009/03/velvet-worms-evolutionary-enigma.html

Margulis published a suggestion that the idea might be worth looking into (an odd idea, but look at how they reproduce; the mechanism is credible, the idea was testable). I see no parallel to Velikovsky; there’s no way to test Velikovsky. The idea has now been looked into, and hasn’t held up.

http://www.pnas.org/content/106/47/19906.full

So that one notion wasn’t right. Some good work got done. The results may yet be useful toward sorting out the “mysterious fog in terms of their exact place in phylogeny” — negative result, perhaps useful work nevertheless.

Why did I poke at this so much? Well, up above RichardC says that in “A space ark or station …. Only desirable species would exist ….”

So I vote for taking Onychophora with us in the space ark.

Georgi #173: “From an evolutionary perspective, we absolutely have to eventually get off this planet and colonize other worlds. Otherwise, in the long term, we are extinct with 100% probability, and not going extinct seems to be the only purpose of out existence.”

I would not call this “not going extinct” the “purpose of our existence”, since eventually everything goes anyway. The sun will consume Earth some 4 billion years from now, and the last star in the Universe will fade away some 1000 billion years from now IIRC (Scientific American did an article about the fate of the Universe last year, which project unavoidable doom in the very distant future).

But your point is correct. If we do not get off this planet, we will go extict much sooner than the end of the Universe. That could be by natural phenomena or a self-inflicted catastrophy or stupidity. For natural causes, There are massive meteors and comets out there that can and will eliminate ‘higher’ lifeforms on this planet, or solar burb or nearby super novas or eruptions of super vulcanos. From these natural causes, the super-vulcano eruptions are interesting, since they seem to occur frequently (Yellowstone erupts every 100,000 years or so, and is long overdue). If Yellowstone blows, you can say bye bye to the USA and Canada, and it is likely that only a few homo sapiens would survive the massive global changes it causes. At best it will set us back 10’s of thousands of years, and life as we know it is gone. But it is interesting to note that there are very few, if any, other natural causes that could seriously damage or eliminate our existence on a shorter timeframe than that.

So, if we do not cause our own demise, then we have some 100,000 years to build self-sustainable colonies in space. That means that Nature’s catastrophy tricks are not going to be our main concern in the short term when it comes to ‘survival’ or ‘getting off this planet’.

That leaves self-inflicted extinction, and within the topic of this thread, the AGW argument comes to mind. And there, again, the timeframe is important. Techno-believers like Dyson would argue that the 3 C increase in global temperature over a century is not a problem. We are used to 10 C differences between day and night, we live in places averaging -20 C to +30 C so we can handle some changes in temps. Also, if AGW causes the Greenland ice sheet to melt over the next 1000 years, then we may experience a rise in sea levels of some 7 mm/yr. We are used to tectonic plate movements larger than that, so surely we can adjust without getting extict. And for other AGW effects (such as agricultural stress caused by profound droughts and rainfall/flooding) these can all be accomodated by improving irrigation systems and flood control. At worst, it would increase insurance rates, but surely it would be hard to argue that our species would go extict because of such changes (which also would happen slowly, over decades and centuries).

In short, techno’s (such as Dyson) reason that if we don’t kill each other in some fluke nuclear war or other self-inflicted immediate catastrophy, there is very little reason to assume that homo sapiens would go extinct on the short term. AGW simply moves too slow in their opinion (even in the ‘business as usual’ scenario) too loose sleep over.

That’s why Dyson is not concerned about AGW.

Hank Roberts — 16 Feb 2011 @ 2:48PM

http://www.istockphoto.com/file_thumbview_approve/4796726/2/istockphoto_4796726-thumbs-up-icon.jpg

The scientific mavericks (not, of course, industry hacks like Patrick Michaels) do take a big risk when coming up with unconventional ideas. The attacks can be withering. I’m reminded of Andrew Wakefield here (which is not to say that I necessarily agree with him). Sometimes though the mavericks turn out to be right as in Igancio Chapela and David Quist’s case. Heck, we could throw in Charles Darwin here and maybe every other original thinker.

Interesting thing is Dyson has been a supporter of Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis/theory. It definitely has merit. Many papers have been written in support of it.

I’m not too fond though of Lovelocks’ suggestion that we should just stop trying since there’s nothing we can do to fix things.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_8594000/8594561.stm

Dyson has an interesting exchange of emails with Steve Connor of the Independent here http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/climate-change/letters-to-a-heretic-an-email-conversation-with-climate-change-sceptic-professor-freeman-dyson-2224912.html#disqus_thread

The difference between Dyson and true innovators like Darwin is that for Darwin, inspiration was only the beginning of the problem. He then went on to search laboriously for evidence that might contradict his ideas. Thus, Darwin looked at some of the most persistent problems for evolution long before any of his critics–the evolution of the eye, altruism in social insects…

Dyson is interested in making provocative statements and leaving the heavy lifting to others. Moreover, if someone raises an objection to his “vision,” he is intereste only to the extent he can rationalize it away. Darwin built an edifice that has grown into the foundation of modern biology. Dyson is content with castles in the air.

Andrew Jackson,

That was disappointing. Dyson has simply lost it.

Interesting that the so-called brilliant heretic, when questioned carefully and respectfully about his views, can do no better than to regurgitate several of the usual tired whines.

[Response: That is the real surprise. Why is someone so smart not making an intellectually worthy critique? It’s like he’s simply dialing his heresy in. – gavin]

I’m currently reviewing “Gin & Tonic” (and yes, I carefully wash my hand afterwards.) I was struck that they quoted Dyson:

It’s ironic for Dyson, as I think was mentioned above–but even more so for G & T, who deal with no climate paper more recent than Callendar, and don’t deign to take notice of the numerous measurements of the very back-radiation that they claim “can’t” exist.

Dyson + climate – is this applicable?