Eric Steig & Ray Pierrehumbert

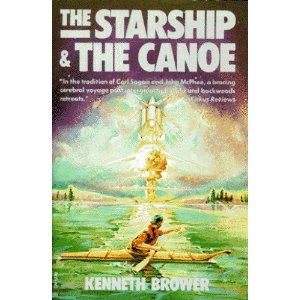

One of my (Eric’s) favorite old books is The Starship and the Canoe by Kenneth Brower It’s a 1970s book about a father (Freeman Dyson, theoretical physicist living in Princeton) and son (George Dyson, hippy kayaker living 90 ft up in a fir tree in British Columbia) that couldn’t be more different, yet are strikingly similar in their originality and brilliance. I started out my career heading into astrophysics, and I’m also an avid sea kayaker and I grew up with the B.C. rainforest out my back door. So I think I have a sense of what drives these guys. Yet I’ve never understood how Freeman Dyson became such a climate contrarian and advocate for off-the-wall biogeoengineering solutions like carbon-eating trees, something we’ve written about before.

One of my (Eric’s) favorite old books is The Starship and the Canoe by Kenneth Brower It’s a 1970s book about a father (Freeman Dyson, theoretical physicist living in Princeton) and son (George Dyson, hippy kayaker living 90 ft up in a fir tree in British Columbia) that couldn’t be more different, yet are strikingly similar in their originality and brilliance. I started out my career heading into astrophysics, and I’m also an avid sea kayaker and I grew up with the B.C. rainforest out my back door. So I think I have a sense of what drives these guys. Yet I’ve never understood how Freeman Dyson became such a climate contrarian and advocate for off-the-wall biogeoengineering solutions like carbon-eating trees, something we’ve written about before.

It turns out that Brower has wondered the same thing, and in a recent article in The Atlantic, he speculates on the answer. “How could someone as smart as Freeman Dyson,” writes Brower, “be so wrong about climate change and other environmental concerns..?”

Brower goes through a number of possible explanations for the Dyson paradox, some easily dismissed (senility; he’s a theoretician with no sense of practicality) some not so easily dismissed (he’s only joking, don’t take it seriously, he doesn’t take it all that seriously himself). But in the end, for Brower, it seems to come down to two conspiring things about Dyson. The first is that Dyson has an abiding faith in the ability of technology to do anything we want it to. It’s not surprising, then, that Dyson thinks we can ‘fix climate’ as well. That, in itself, makes Dyson not so much a “global warming skeptic” as an extreme techno-optimist. In fact, even leaving technology aside, he has a touching faith that whatever humans may do to the environment, it usually turns out for the best. In this essay, he writes:

“The natural ecology of England was uninterrupted and rather boring forest. Humans replaced the forest with an artificial landscape of grassland and moorland, fields and farms, with a much richer variety of plant and animal species. Quite recently, only about a thousand years ago, we introduced rabbits, a non-native species which had a profound effect on the ecology. Rabbits opened glades in the forest where flowering plants now flourish.”

We daresay that the Australians have a somewhat less benign view of rabbits (as the New Zealanders do of possums). And that maybe Dyson has a thing or two to learn about the biodiversity of unmanaged ecosystems.

Second, Dyson’s obsession has always been the stars, not the earth: he spent many years working on the design of a spaceship (hence the title of Brower’s 30-year old book) that would take him there. It’s not so much that he doesn’t care about our home planet — he must have learned something about ‘spaceship earth’ from son George over the years. Rather, he is simply very confident that we can always get off if we have to. “What the secular faith of Dysonism offers,” Brower writes” is, first, a hypertrophied version of the technological fix, and second, the fantasy that, should the fix fail, we have someplace else to go.” Dyson has stated in many places, and in various ways, that he thinks global warming is not a big problem, and that its importance has been exaggerated. To put things in perspective, though, Dyson doesn’t particularly think that the extirpation of all life other than human would be a particularly big deal “We are moving rapidly into the post-Darwinian era, when species other than our own will no longer exist, and the rules of Open Source sharing will be extended from the exchange of software to the exchange of genes,” he is quoted as saying in Brower’s article. Dyson’s idea of what constitutes a “big problem” may be, well, just a bit different from what most of the rest of us might have in mind.

Brower’s conclusions sound right on the mark to us, but don’t fully explain Dyson. Perhaps Brower is being gentle, since he is an old friend, or perhaps he simply isn’t aware of it, but one issue he does not touch on in his article is is how deceptive (apparently deliberately) Dyson can be.

The problem is that Dyson says demonstrably wrong things about global warming, and doesn’t seem to care so long as they support his notion of human destiny. Brower reports that Dyson doesn’t consider himself an expert on climate change, has no interest in arguing the details with experts, and yet somehow knows that the experts don’t have any answers worth listening to. That doesn’t stop Dyson from making sweeping pronouncements, many of them so egregiously wrong that it would hardly have taken an expert to set him straight.

The examples of this are legion. In the essay “Heretical thoughts about science and society” (excerpted here) Dyson says that CO2 only acts to make cold places (like the arctic) warmer and doesn’t make hot places hotter, because only cold places are dry enough for CO2 to compete with water vapor opacity. But in jumping to this conclusion, he has neglected to take into account that even in the hot tropics, the air aloft is cold and dry, so CO2 nonetheless exerts a potent warming effect there. Dyson has fallen into the same saturation fallacy that bedeviled Ångström a century earlier.

And then there are those carbon-eating trees. He likes this one so much he put it in both the Heresy essay and in his piece in NY Review of Books. He points out that the annual fossil fuel emissions of carbon correspond to a hundredth of an inch of extra biomass per year over half the Earth’s surface, and suggests that it shouldn’t be hard to tweak the biosphere in such a way as to sequester all the fossil fuel carbon we want to in this way. Dyson could well ask himself why we don’t have kilometers-thick layers of organic carbon right now at the surface, resulting from a few billion years of outgassing of volcanic CO2. The answer is that bacteria have had about two billion years to evolve so as to get very, very good at combining any available organic carbon with oxygen. It is in fact extremely hard to put organic carbon in a form or place where it doesn’t get oxidized back into CO2 (Mother Nature thought she had done that trick with fossil fuels but we sure fooled her!) And if you did somehow coopt ten to twenty percent of the worldwide biosphere’s photosynthetic capacity to take up carbon and turn it into a form that couldn’t rot ever, you’d have to sort of worry about how nutrients would ever get back into the ecosystem. And also maybe whether the carbon-eating trees might get out of control and suck out so much CO2 you wound up in a Snowball Earth.

Dyson espouses a generic disdain for climate models and climate modellers: ” Here I am opposing the holy brotherhood of climate model experts and the crowd of deluded citizens who believe the numbers predicted by the computer models.” Like most of us, he has little confidence in the modelling of clouds. But with great ignorance of the nature of the modelling enterprise, he declares: “It is much easier for a scientist to sit in an air-conditioned building and run computer models, than to put on winter clothes and measure what is really happening outside in the swamps and the clouds” Actually, those of us who go to Antarctica to drill ice cores certainly put on winter clothes, and paleoclimatologists are out in the swamps and ocean muck all the time. And there are plenty of scientists flying around in the clouds, trying to gauge their effects. The mainstream estimate that the climate sensitivity is around 3°C for a doubling of CO2 does not simply comes from computer models. Study of the Last Glacial Maximum, the Pliocene and the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum all rule out the idea that there is a strongly stabilizing cloud feedback. Ahe fact that we cannot precisely quantify cloud feedbacks also means that there is a lot of risk, that cloud feedbacks could make a doubled-CO2 world much hotter, not much cooler. Dyson’s writings conveniently ignore this two-directional implication of uncertainty, and they they also ignore the implications of the long atmospheric lifetime of CO2, which means if we wait and see how hot it gets and find we don’t like it, there’s nothing much to be done (unless, of course, we can simply go somewhere else).

Finally, there is the familiar examples of Dyson attacking the style of the debate, rather than its substance. Reporting on written debate between Richard Lindzen and Stefan Rahmstorf, in the New York Review of Books New York Times book review, Dyson juxtaposes Lindzen’s claim that “observations suggest that the sensitivity of the real climate is much less than that found in computer models” with Stefan calling this “simply ludicrous”. Dyson gives the impression that rational arguments from skeptics are met with “open contempt” by the majority. But he fails to mention that Stefan showed in detail why Lindzen’s claim is wrong: Lindzen ignored ocean thermal inertia when comparing observed warming with the equilibrium climate sensitivity. Any physicist should be able to judge that Stefan is right and Lindzen is wrong on this point. He also failed to mention that Stefan used the word “ludicrous” only in a “personal postscript” to a completely sober scientific article, referring to Lindzen’s claims that a vast conspiracy of thousands of climatologists worldwide is misleading the public for personal gain. Dyson’s account of the Lindzen-Rahmstorf exchange neither fairly covers the substance of the argument, nor is it a fair portrayal of its style – Dyson seems to have twisted it as much as he could to score a political point.

In the Heresy essay, Dyson repeatedly gives himself a way out by claiming he is only tossing out ideas that should be thought about; he at times emphasizes that he does not know the answers, only the questions that should be raised. However, that does not stop him from making confident claims that he has a broader view than others, as in this interview with Mike Lemonick, and somehow Dyson never gets around to thinking about what the consequences are if we continue inaction on CO2 emissions and he turns out to be wrong. More importantly, all of the things Dyson argues “heretically” should be looked at — e.g. land carbon sequestration or the lessons from the Altithermal period around 8000 years ago — are in fact already being intensively investigated and are not turning up any silver bullets to allay concern about climate change. When push comes to shove, Dyson is really only offering warmed-over standard contrarian talking points. Heresy, or more broadly an outsider’s viewpoint, can be a good thing when it shakes loose new ideas. But surely, we have a right to expect a more original form of heresy from the architect of Dyson spheres and nuclear starships.

In short, it’s not so simple as the ‘self delusion’ Brower talks about. Dyson is not doing science, but he is deluding others under the guise of science. Given’s Dyson’s evident love of science (and expertise in it), that’s the part that we still don’t get.

#77–“But think of the really cool bonus… the Moon’d look like the Death Star!”

Yeah, and if we got disgruntled Lunar colonists a la Moon Is A Harsh Mistress the Moon could really BE a Death Star if equipped with 10,000 13 GW microwave beams!

#77–J Bowers–

And if we got disgruntled Lunar colonists, as in The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress, those 10,000 13 GW microwave beams could actually MAKE the moon a Death Star, too!

Or should I be referencing another literary trope here, and saying that your take on the idea is that it is “mostly harmless?”

@Brian Dodge

Hello Brian. I read the articles you linked to and I didn’t find any mention of the medieval warm period.

[Response: I said, Discussions of MWP are off topic on this thread. Take it somewhere else. –raypierre]

Off the top of my head, rabbits were introduced to England by the invading Romans in 56bc, not 1000 years ago. And though the British Isles were, indeed, once heavily forested, the pre-Roman inhabitants had cleared so much forest that the Roman commentators remarked on it.

Shorter Russell Seitz @ 97

Stupidity should rule

Jim wrote: “… what can be achieved, and what behavioral actions we need to implement in order to do that …”

Russell Seitz replied: “… your enthusiasm for social engineering is not universally shared …”

So building wind turbines is “social engineering” … and building coal-fired power plants is what, exactly?

Insulating your attic is “social engineering” … and wasting money and energy to heat a poorly insulated house is what, exactly?

Two of the last three years have seen extraordinary prices for food due to crop failures.

As an opening to any future discussion of consequences due to AGW, that’s a good place to start since I don’t think the heavy stuff will come down for a while. Let the likes of Dyson go hungry two out of three years and see if they’re still convinced it’s no big deal.

Because someone is talented in one area of science, it doesn’t automatically follow that they will be talented in other scientific areas.

Also, ideology, one’s system of beliefs, often, if not always, trump objective reality. What one believes is usually more powerful and closer to one’s heart, than what one knows.

But the basis of science is seeing clearly regardless of one’s own beliefs, or the beliefs of others.

98, deconvoluter: Isn’t that comparison between late Einstein and Dyson unfair to the former? Being wrong on occasions is not the same as being serially superficial about a big topic.

I agree. Einstein is more profoundly difficult to understand (I think) because he was originally a pioneer in the probabilistic modeling of micro phenomena (photo-electric effect, Brownian motion and diffusion, Bose-Einstein statistics), before he revolted against his own approach; and he was persistently (“serially”) resistant to the advances in probabilistic modeling for approximately the last 4 decades of his life. His stated reasons (“God does not play at dice”, “This does not bring us closer to The Old One”) are seemingly irrelevant to all his other work, and unusually arrogant to believe that he know the mind of God. He also ignored the accumulating record of success in quantum mechanics.

The only general principle that they both illustrate (along with Newton, Kepler, and others) is that the motivations and thought processes of other people are exceedingly difficult to understand.

Kevin (#101-2),

but then, they’d be in a position to drop rocks down our gravity well anyway…

BTW, Dyson really should have taken a cue from Heinlein’s heroes in Moon is a Harsh Mistress, who fought their revolution to stave off the imminent ecological collapse of their world as foretold by computer modeling.

\Yet, they still managed to drive the moa to extinction, and perhaps the North American megafauna also.\ – raypierre

In fact, everywhere outside Africa, the arrival of Home sapiens sapiens was closely followed by mass extinctions of megafauna.

Russell Seitz,

What exactly is supposed to be wrong with “social engineering”? Every time a law is passed, an firm or political party or pressure group or charity is founded, an advertising campaign is launched, a book advocating some proposal or idea is published – that’s social engineering. The right-wing use of the term as a sneer is ridiculous (and is, of course, an example of social engineering).

Edward Greisch, I think you are assuming that everything you don’t understand must be easy. There is more to good legislation than technical content. People must be able to live within the strictures of the law without rebelling against it. If they cannot do so, the law will be voted out with the next election. In some cases the endangered species act has actually hurt rare species because landowners kill them off before they can be discovered by regulators.

Septic Matthew: “Einstein … was originally a pioneer in the probabilistic modeling of micro phenomena … before he revolted against his own approach; and he was … resistant to the advances in probabilistic modeling for approximately the last 4 decades of his life.”

I think that’s not really right. Einstein didn’t have a problem with probabilistic modeling and he certainly appreciated the fact that quantum physics “worked” (e.g. the mathematics successfully predicted the results of observations).

What Einstein objected to was the idea that concepts like indeterminacy, uncertainty, nonlocality and complementarity were not just aspects of the abstract models but of physical reality itself.

112 Ray Ladbury: “I think you are assuming that everything you don’t understand must be easy.”

NO. But I am saying that non-scientists do NOT have some kind of intelligence that scientists lack.

[Response:That depends on what you mean by intelligence. I prefer the word “understanding”. We need the perspective that much of the humanities brings. Technical information alone ain’t going to get it done.–Jim]

““Brower reports that Dyson doesn’t consider himself an expert on climate change, has no interest in arguing the details with experts, and yet somehow knows that the experts don’t have any answers worth listening to. … “,

I don’t know how true that is of Dyson, but if we take it at face value i.e. that Brower’s assessment is broadly correct, then it means Dyson has just closed his mind to any serious, informed discussion of the subject. Just goes to show how a great scientist can be as easily mistaken about a topic as anyone else when they are not prepared to read up about it and want to ignore inconvenient facts. I find the dismissal of models and modelling particularly irksome: where the hell would we be in most of our engineering and science if we didn’t have people prepared to try to build good models and use them?”

I think you are missing the point. No doubt modelers have important stuff to pass around and sell to other modelers and climate scientists. But the state of the science has little to offer to the general public. One can have a learned opinion based upon the details but still the opinion needs to be put to a carefully calculated cost/benefit analysis and the guy with the least proficiency in doing that is the guy most heavily invested.

The primary sign of a lack of useful product is when you see commodities finding a market such as upside down proxies, single trees in some Siberian forest, covering up declines, one decade going on about how end of snowy winters is nigh and the following decade attributing snowy winters to what was predicted. There would be no market for any of this if what was being delivered to the general public was useful. Saying the devil is in the details is like a long winded talk, the only reason it is long winded is usually the guy giving the talk really has very little to say and he is hoping if he keeps talking something worthwhile will arise from it.

[Response: This is the second time I’ve heard meaningless and gratuitous insults from you regarding “upside down proxies” etc. Getting pretty boring. –raypierre]

104: ( et seq.)

“Shorter Russell Seitz @ 97

Stupidity should rule”

Eli, social engineering and universal suffrage all too often combine to that end, but we digress .

Dyson made material contributions to solid state theory, and helped kick start computational hydro codes

#110 “In fact, everywhere outside Africa, the arrival of Home sapiens sapiens was closely followed by mass extinctions of megafauna”.

Apart from islands like New Zealand the extinction of the megafaunas were, ironically, more likely due to climate change.

[Response: The jury’s still out on that. Read for example Paul Martin’s work. Over-hunting is a definite possibility in places such as N America.–Jim]

I always like to think of denialists as diprotodonts queuing at a rapidly-drying water hole.

Professor Pierrehumbert: Regarding part 2 of your Dyson sphere question: “If you tried to put an atmosphere on the inside (livable) surface of a Dyson sphere, where would it go?”

I’ve enjoyed contemplating this and I appeal to everyone’s forgiveness for my making a back of the envelope guess while out of my field…

And assuming this is a one-walled Dyson sphere rotating to simulate 1 gravity, and that the atmosphere is inserted quickly and has the angular momentum of the sphere…

I think the atmosphere will experience two forces: one a tendancy to collect at the equator from the angular momentum, and two, a tendancy to escape along the sphere to higher latitudes. As the gas encounters lower simuluted gravity at higher latitudes it would rise into cones over the north and south pole and spiral into to star.

??

I’ll check my guess as I study Chapter 2.

jg

[Response: You’re certainly on the right track. I didn’t put this in Chapter 2 because it does involve some stuff about centrifugal force and gravity I didn’t really discuss explicitly, but with some knowledge of those two things plus the thermo (esp. hydrostatics) in Ch. 2. you can get the answer. I won’t spoil the fun here. Does everybody understand why you need to spin the sphere to simulate 1 gravity? And why you don’t wind up getting 1g everywhere? –raypierre]

I suspect that a lot of the action is about to wander over to the Odonnelgate thread, but before I lose your attention entirely, I want to say a few words about the intent of our Dyson article.

Some have taken this as an invitation to dump on Dyson, but that wasn’t really the point. Dyson is not Dr. Strangelove, and he’s certainly not a manipulative self-aggrandizing egotist like Claude Allegre. He ia a thoroughly agreeable and affably dotty academic who has a lot of interesting things to say but is not especially well informed about climate or most of the other things he writes about. So, one shouldn’t take home the message that, “Dyson is a great physicist and says there’s something wrong with our approach to global warming, so that should carry a lot of weight.” As we’ve argued, he is not well informed and has not thought these things through any better than the pronouncements on bioengineering he has made. What makes Dyson interesting is not his insights about the scientific aspects of what he is talking about. That is shallow, and often wrong. What makes him interesting is his philosophy, in particular his views of the destiny of humanity. This philosophy is defined by the dichotomy (false, I think) he sets up between “environmentalism” and “humanism.” In this he has a lot in common with Teilhard de Chardin. The comments here have raised enough interesting points about the place of humans in nature that I decided it is worth writing a separate post exploring these ideas. Stay tuned!

Bill Hunter, OK, let’s talk about probabilistic risk assessment. What’s step one, Bill? Why, bounding the risk. Do you know of a single study that has convincingly bounded risk for climate science? I don’t and it is not for lack of searching. Even if you look just at the CO2 sensitivity PDFs, the admittedly small probability that S is greater than 4.5 degrees per doubling dominates risk, because the consequences are so much more grave. So, Bill, what is a risk mitigation professional to do when confronted with a threat that carries unbounded risk and the potential for unlimited loss? The only acceptable answer is to avoid the threat, and the only way to do that is to limit CO2 emissions.

There is a reason for the classic joke about physicists that starts with “Postulate a spherical chicken … ” and Dyson is a good example.

JBowers @52 – I’ve often wondered why, if cost effective energy transmission is feasible, why this couldn’t be the basis of a global energy grid? Hell of a lot easier (probably cheaper too) to have solar farms across the world’s deserts than in orbit or on the moon, even if they don’t run 24/7 (in orbit) or 14 days per 28 (on the moon). If the energy can be sent from where it’s sunny to where it’s needed.

I don’t have problems with Big Ideas wherever they come from (Dyson has thrown out a few) but we have real constraints including environmental ones. A global grid is one Big Idea, one I think probably does deserve some consideration. And it looks more achievable than solar farms on the moon. But I’d rather not place all our bets on it when it looks like it gets less serious R&D than boiler efficiency in coal power plants.

I was making models of the actual sinks for a project, and his statement that they were all around the same size was off by orders of magnitude. He also said there was a perfect system of negative feedbacks. I don’t think you need that much expertise, really. He says stuff that would get you a solid reputation as a crank anywhere, anytime.

“Does everybody understand why you need to spin the sphere to simulate 1 gravity? And why you don’t wind up getting 1g everywhere?”

That would be the consequence of the (nowhere near as salacious as it sounds) hairy ball theorem. It’s impossible to rotate a sphere in such a way that you won’t have at least one point where the velocity is zero.

If such an enormous undertaking were possible (“mammoth” doesn’t even begin to describe the scale of the task), ring worlds a la Halo would be where it’s at.

[Response: That’s half the answer. As for the other half, here’s a hint. What’s the gravity field within the space enclosed by a shell of matter? –raypierre]

RE # 36

Ray, I followed your suggestion and read Dyson’s essay published in NYBR to which you provided a link.

The part I found most defines his thought process is in the following:

Imagine a child playing in a woodland stream, poking a stick into an eddy in the flowing current, thereby disrupting it. But the eddy quickly reforms. The child disperses it again. Again it reforms, and the fascinating game goes on. There you have it! Organisms are resilient patterns in a turbulent flow—patterns in an energy flow…. It is becoming increasingly clear that to understand living systems in any deep sense, we must come to see them not materialistically, as machines, but as stable, complex, dynamic organization.

This from a man who spent a great part of his life understanding, accepting and then utilizing quantum electrodynamics. He will never see an electron but he has a working knowledge of its 13.7 billion years of never failing to do what it was designed to do. Just as that flowing current can be affected but not changed by an intermittent poking of a stick.

He cannot accept AGW because it defies the order of a planet he suspects but is only vaguely familiar. He has no answers to provide on how, if AGW is the greatest challenge to have ever faced humanity, it might be contained.

One will have the same kind of reaction from Larry Summers if he was challenged to offer a fix of America’s economy if China and other central banks refuse to buy our debt.

Brilliant people have the convictions of their beliefs when they are in control of the facts. Neither Dyson nor Summers have the knowledge of the complete workings of the systems they have devoted their lives trying to understand. In other words, their comfort level demands they always be in command of their point of view. That is why he is reluctant or refuses to debate honest scientists. He has no tolerance, in his thinking, for being proven he is wrong.

Regarding the atmosphere in a Dyson sphere problem, I have to ask: should I assume 1) the Dyson sphere has an Earthlike IR reradiation but inward from the inner surface; or 2) the sphere is converting all solar energy to other forms and is therefore IR neutral on the inside; or

3) the sphere was constructed to be an inverted globe in how much it radiates IR on the inside, so that the equator emits the most IR inward and IR reduces as you climb to higher latitudes (a lot like inverted insolation on a globe).

(Am I barking up the wrong tree? Am I barking up A tree?)

thanks,

jg

[Response: Well that’s where the fun begins — it’s your Dyson sphere, so you can design it any way you want (compatible with sound radiation physics). But regarding your question on insolation and latitude, you are getting a bit confused about the geometry. It’s high noon all the time everywhere on the inside surface of the sphere. There’s no differential solar heating, though variations in the material properties of the sphere or the atmosphere could still give you a temperature gradient. Regarding conversion of absorbed solar to IR — that’s fully determined by energy balance and the physics of blackbody radiation. You don’t have any choice there, UNLESS you harvest a significant part of the energy using photovoltaics or something like that, and use the energy to do something that doesn’t give back all the energy harvested as heat locally. For example, you might use the photovoltaics to drive a laser beacon to other stars, in an effort to touch base with other civilizations. –raypierre]

Bill Hunter:

Information isn’t a commodity. I wouldn’t go so far as to say your whole world-view is wrong, since I really don’t know what your world-view is. But you have some odd ideas!

I think normal evolution has done quite well so far, except that it has managed to evolve a species whose technological capabilities have far outstripped the development of a moral compass that would allow that species to use its capabilities wisely. –raypierre Very philosofical, can I use that?

[Response: Be my guest! You are most welcome to use my bon mot. –raypierre]

Oops, sorry – forgot to address that part. Yes, inside any homogenous spherical shell, the net gravitational force due to that shell is zero at all points. So you need to spin your construct to get artificial gravity.

Just how *fast* you need to spin it is also interesting. To get an outwards force of 1g at Earth’s orbit, you’d need to speed up the orbit to just nine days. With a tangential velocity of ~1200 km/s.

Yeah… Now imagine what would happen if it developed a crack.

[Response: … which is no doubt why we are seeing so many disk-like infrared emitters out there in the galaxy. –raypierre]

In case no one has mentioned it, let me suggest that the phenomenon of emeritus physics professors pretending to be experts on subjects that are not their own, and making a complete hash of it, is not exactly uncommon.

I don’t think a more complicated explanation is really necessary. Good old fashioned egotism is enough.

Raypierre,

The Dyson sphere discussion is fun, as it reminds me of discussions I had on sci.astro.seti (in the time that it was still buzzing with creative and scientific people alike).

For now, I have a more mondaine question.

The main post states :

“Study of the Last Glacial Maximum, the Pliocene and the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum all rule out the idea that there is a strongly stabilizing cloud feedback.”

and in post #34, you comment :

“The PETM in fact tends to support climate sensitivity at or somewhat above the top”

When I debate with ‘skeptics’ and AGW deniers, the issue of climate sensitivity and paleo-evidence for CO2 causing warming often comes up, and I would like a reference to the studies that you refer to here, so I can use it during in arguments.

Specifically, I’m looking for a study that confirms that changing levels of CO2 must have contributed to the temperature swings between glacials and inter-glacials. Since Milankovitch cycles create 50-80 W/m^2 irradiance swings between the Hemisphere’s, it is not easy to validate that CO2’s forcings swings (presumably in the range of 2-4 W/^2) could have much of any influence.

Note that this is one level below the ‘climate sensitivity’ discussion, since climate sensitivity is already assuming that CO2 at least caused a part of the glacial-interglacial temperature swings.

Any good source for studies done in this area would be appreciated.

Thank you.

P.S. A logistical suggestion for the RC comment section design : The number of comments on RC posts is typically in the hundreds, and with the single list of comments (also broken into pages with 50 comments each) the comment section is void of structure and context. Hence people need write RE # notes to refer to other comments, which are in turn hard to find back.

Is there a chance that RC could possibly provide a ‘thread-based’ comment section, rather than the single heap we now work with ?

That (thread-based comment section) is actually something I like from the climateaudit site (sorry!).

As an example of why a thread-based comment section is helpfull, here

http://climateaudit.org/2011/02/07/eric-steigs-trick/#comment-253866

is my latest post there which still stands with the responses nicely organized (and still unanswered by O’Donnell et al :o)

Rob @132 — Your question is OT on this thread. I’ll provide a patial answer on this month’s Unforced Variations thread.

[Response: I declared the pointless MWP trolling off-topic, but please do feel free to respond to Rob on this thread. I think it’s on topic here, because it relates to issues I raised in the post and in my comments. As for my two bits, you can get some idea of the implications of the Pliocene from Lunt et al in Nature Geoscience, and for the PETM from the nice perspectives piece in Science by Pagani et al. The LGM is trickier, because there are a lot of forcings involved, but Milankovic isn’t much of an issue because in the Southern Hemisphere the ocean averages out a lot of the seasonal variation and what’s more during the LGM itself, the insolation wasn’t incredibly different. There is some review of the LGM implications in the Knutti and Hegerl paper on climate sensitivity in Nature Geosciences, but the LGM example is one of the trickier ones — but still, a strongly stabilizing cloud feedback would have made it hard for the Southern Hemisphere midlatitudes to cool by 4C, largely in response to the CO2 reduction. I’ll need to dig up links to the specific papers to make things easier for our readers, and hopefully will get to that later. Meanwhile, I’d be interested in your take on this. If I had to pick one thing that really scares me, it’s the Pliocene, which was a very different world even though (as Mark Pagani assures me) nobody has a credible estimate for Pliocene CO2 higher than 450 ppmv. –raypierre]

Rob (from another thread) — Rather than glacial cycling, let’s go back to the mid-Pliocene when CO2 levels were comperable to today’s and, as a consequence, there was very little ice anywhere:

Earth system sensitivity inferred from Pliocene modelling and data

Daniel J. Lunt, Alan M. Haywood, Gavin A. Schmidt, Ulrich Salzmann, Paul J. Valdes & Harry J. Dowsett

Nature Geoscience 3, 60 – 64 (2010)

http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/v3/n1/full/ngeo706.html

In addition, Tamino has two recent threads on galcial cycling which may answer some of your questions:

http://tamino.wordpress.com/2011/01/29/glacial-cycles-part-2/

More generally, you should study “The Discovery of Global Warming” by Spencer Weart:

http://www.aip.org/history/climate/index.html

(if you haven’t already).

[Response: I took the liberty of moving this back to the Dyson thread. Thanks for the sensitivity to being OT, but I think it’s OK here, since I raised the issue myself. –raypierre]

It’s strange to see scientists behave like Neanderthals when confronted with evidence that they don’t like. My guess about Mr Dyson is that he is a Libertarian of the Julian Simonesque, Michael Chrichton and CATO variety. He just sounds like one to me.

Libertarians, as a party, don’t seem to have much regard for the planet that produced them and continues to give them life. They are much more at home in white, sterile rooms then sunny, green meadows. Their irrational (almost fundamentalist) feeling is that the earth exists solely for our use, and thus we should use it up and then discard it like any other rubbish. They are all big believers in the notion that technology will be (and should be) our savior. They regularly fall for the delusion that we can easily find other habitable planets (or spheres) to emigrate to (or build) because they’re simply itchin to get off this one. And so they find environmentalists, which call for earth’s conservation, Highly annoying. If they can speed up the transition off this planet and to outer space by monkey wrenching environmentalism then they are all for it.

Some people just seem to have, as Muir put it, “a perfect contempt for nature”. A perfectly insane contempt for nature that is.

[Response: “No dogma taught by the present civilization seems to form so insuperable an obstacle in the way of a right understanding of the relations which culture sustains to wildness as that which regards the world as made especially for the uses of man…Yet it is taught from century to century as something ever new and precious, and in the resulting darkness the enormous conceit is allowed to go unchallenged.” John Muir.—Jim]

I did a google scholar search on “f dyson”. of the first 45 hits only 6 had co-authors. (5 of the first 50 were KHF, BF, or FW dysons)

I think he’s used to being an independent thinker, and just assumes that he knows enough about all aspects of any problem that catches his interest that he rarely needs to involve others.

Doing a search for ga schmidt, the stats are reversed – only 4 single author papers, the rest collaborations (and a few random hits).

Raypierre, David,

Thank you for all the good refences. I’ll read up on these and see to which extend they would ‘close’ the loopholes used by critics.

There is bell curve of levels of denial and skepticism out there, and even though the scientific case for AGW is very strong, as scientists, we need to make sure that every possible alternative to this planet’s warming trend is at least quantified and provide evidence for it’s significance. Otherwise we would be overstretching our conclusions and that leaves climate science volnerable to (in that case ligitimate) criticism of the smarter part of the bell curve. So evidence in the form of scientific studies on all aspects of climate science are important for every statement made by anyone arguing in the name of science (and here on RC specifically).

AGW skeptics (at least the smart ones) are very good in finding error with others, but their weak spot is scientific evidence, and sometimes you have to go very far to disprove their argument. For example, when somebody pointed me at Lindzen and Choi as proof of strong cloud feedback, I had to go all the way to find and point out the mistake in Lindzen’s paper, and then post that on contrarian web sites.

http://motls.blogspot.com/2009/11/spencer-on-lindzen-choi.html

Ultimately that caused Spencer to criticise Lindzen on scientific grounds. Trenberth 2010 knocked out any credibility of Lindzen and Choi eventually, and Lindzen to admit the mistakes, but for me this excercize showed that if you have your science right (every avenue closed), and do not overstretch arguments, that you can stand up to any ‘skeptic’ or ‘denier’ and come out stronger, as well as be relentless in your responses.

But every detail of what we write has to be sustained by (scientific) evidence. Leave no room for error.

That is why the argument for the influence of CO2 on our climate has to be shown way beyond ‘reasonable doubt’. Not just to show that ‘skeptics’ have no case, but much more to show the world that we have undisputable evidence of CO2’s infuence on past climates, and that we have significant evidence of the timeframe that effects of warming will play out.

In that respect, I truely appreciate that you ask my opinion on the Pliocene.

The best evidence we have is that the Pliocene was some 2-3 C higher than today and sea level was 20m higher. But if paleo climate science cannot show a higher resolution than say 4000 years, then we cannot prove more than 5mm/year sea level rise and thus it would be hard to argue that CO2’s influence will be more significant than plate tectonics, which also change by the same order of magnitude. I know, I know, there is a ‘risk’ that it will go much faster than that, but if we cannot quantify the rate of change, or even that risk, then we are not talking scientifically.

And then, how do we know how much of that 2-3 C was caused by the higher CO2 concentration and not by, say, a change in ocean currents (which could very easily distribute heat across the planet more evenly than what happens today).

Sorry if this response was more than you asked for, but I wanted to show you what kind of arguments I am dealing with I stick my head into these contrarian web sites and argue with AGW skeptics on news groups.

“Apart from islands like New Zealand the extinction of the megafaunas were, ironically, more likely due to climate change.” – calyptorhynchus

Then why didn’t such mass extinctions happen on previous occasions of similar climate change? Why did the continental mass extinctions happen sooner in Australia than in the Americas, and in both case, the evidence suggests, largely soon after human arrival? (These are the clearest continental cases, as modern humans were the first hominids to arrive, and spread very rapidly: in Eurasia, there was a considerably slower northward spread as cold-weather technology improved.) Why, when the cases of New Zealand, Madagascar and numerous smaller islands in more recent times are clearly due to human arrival, should the same processes not have operated on a larger scale?

“I don’t have problems with Big Ideas wherever they come from (Dyson has thrown out a few) but we have real constraints including environmental ones. A global grid is one Big Idea, one I think probably does deserve some consideration. . .”

Personally, I’ve developed a hearty distrust of Big Ideas. It’s not that I don’t appreciate or enjoy them, nor that I’m insensitive to their appeal. It’s rather that they appeal too much–providing a clarity and simplicity that is altogether too seductive, for me and (if history is a guide) to many others. If “the devil is in the details,” then a Big Idea at first blush looks like the ultimate exorcism.

But of course, each Big Idea then breeds its own complement of details–and worse, since no Big Idea is actually Big enough to encompass the entire Universe in all its richness (however much its advocates may delude themselves otherwise), a vast crowd of “secondary” details arises from what we might call “interface issues.”

And those are the really dangerous ones, since a really bad case of Big Idea-itis tends to lead to denial that those interface issues even exist. I’d say we’ve seen a few examples of that here on RC, and in the wider discussion about AGW-related policy too–both for mitigation and for geo-engineering. (Though geo-engineering seems particularly prone to the grandiose.)

All of which is a long-winded way of saying that I think the “stabilization wedges” concept, which envisions flexible combinations of smaller-scale mitigation measures, is more likely to be helpful than any one “Big Idea” for mitigation.

About the Dyson sphere, I always understood it to be meant to consist of independent particles, like the rings of Saturn. So, a collection of free-floating space colonies orbiting a central star. I remember seeing such visions already in the space literature of the fifties (Willy Ley?)

One problem with a solid Dyson sphere, or a Niven-Pournelle ringworld, is that it would eventually crash on the central star if it were rigid. Some sort of active control is necessary, like also for the ring of shadow squares inside it. This quite apart from the minor problem of finding a material strong enough to resist the centrifugal force if it spins to generate gravity… a problem the authors solved by just postulating such a material :-)

[Response: Making a dense sphere of free-orbiting O’Neill habitats is not so easy. You’d have to have a bunch of orbits at different inclinations and probably slightly different orbital radii, but then the traffic control problem to prevent collisions would be pretty severe. Still, a configuration like that would be far less problematic than a rigid Dyson sphere rotating to produce gravity — especially because of the material strength difficulties, the stability problem, and the fact that (barring invention of gravity generators of some sort) almost all of your atmosphere would congregate around the equator of the sphere. (Exercise for the reader: compute the density of an O2/N2 atmosphere as a function of latitude on the sphere and altitude above the inner surface. You may assume the temperature of the atmosphere to be isothermal, or on the dry adiabat, to keep things simple. ). –raypierre]

Above all else, the “Starship and the Canoe” is about two very different philosophies.

One philosophy is about “living with nature” (eg, George Dyson living in a tree-house, building sea kayaks and paddling around the Pacific Northwest coast).

The other philosophy is basically about the “control of nature.”

Freeman Dyson has spent his entire life embracing the latter philosophy: dreaming up ideas of genetically engineered “tree factories” (to produce chemicals and suck CO2 out of he air), bopping around the stars in nuclear powered star-ships, and the penultimate “control of nature”, producing atom and hydrogen bombs (though he was not directly involved), harnessing the power of a black hole.

Dyson’s faith in the power of humans to control the physical world stems from a system of beliefs and values (an ideology) that has been around for a long time — but which really came to the fore under Newton and reached its pinnacle with the production of the atomic and hydrogen bombs.

It’s really no surprise, then that Dyson would see no real problem with “controlling” our way out of any issue with too much CO2. After all, to someone like Dyson who witnessed the development of the atomic and hydrogen bombs, CO2 extraction from the air may seem like a small engineering problem in comparison.

> paleo climate science … resolution … 4000 years

Sez who, Rob?

Kevin @ 139, I wasn’t proposing we throw all our resources into one Big Idea and neglect what we know we can do right now. I don’t oppose efforts to develop Integral Fast Reactors or even ongoing R&D into Fusion ones but not as an excuse to fail to do what we can now. Improving long distance energy transmission via HVDC or (Big Idea) superconductors – or whatever might be made to do the job – deserve some effort too. There are lots of constraints besides the technological and direct environmental ones such as limits on time and money. But the biggest limit of all is the limit of willingness to actually commit to serious policy on climate and energy.

Still, I have yet to get a response from the proposers of space based solar (I ask this whenever I encounter them) for why, if energy can be beamed down successfully, this technology could not be used to beam up, over and back down.

Kevin, can I add that I suspect the primary motivation of space power proponents is not the solving of problems down here on Earth but to enable the colonisation of space – something Dyson has been a proponent of. I also suspect an element of doomism; Earth being somehow beyond human abilities to manage sustainably and sending off an elite selection of superior humans into space will somehow sustain our species beyond the use by date of our planet.

#143, 144–

I wasn’t criticizing your ideas, Ken; more just going off on a semi-related tangent. FWIW, I suspect your suspicions in #144 may have some justification.

Although I’d love to see space exploration–I want to say “take off,” but that would be bad–flourish, for that to happen at the cost of this world would be a fool’s bargain indeed. But I don’t think it’s either/or, if we can get through our current sustainability crisis.

In some ways, the Dyson sphere is sorta silly. Since you have to spin it to maintain gravity, there’s only a relatively small percentage of it that’s livable. As you go further from the circle that’s perpendicular to the axis of the spin, the apparent gravity would be at an angle to the ground under your feet. For this reason alone, I prefer the ring world. Not that this preference has much bearing on my life, as no-one has invited me to live on either kind of habitat. HINT, HINT, HINT….

The third possibility is that Dyson is correct.

Kevin, oddly enough I think space habitats would require closer and more regulated attention to environmental issues than anything seen to date on Earth. Anyone imagining that there would be less regulation and more individual freedom within a space habitat is seriously kidding themselves; workaholic perfectionists willing to follow plans and procedures, fanatic recyclers more concerned about air and water contamination than the most extreme Greens and completely dependent on the resources and most advanced products of Earth for the foreseeable future. And I suppose the people of Earth would be expected to pay for the whole exercise. But human nature, with all it’s messiness would still go wherever humans go. Selection for superior intellect doesn’t guarantee anything; imagine a thousand Dysons trying to agree on anything! And their kids may not find following in Daddy’s footsteps their idea of a fulfilling life even if the fine line between life and hard vacuum is strong incentive to try their best.

> third possibility

And we all fervently things work out that he is somehow correct.

Designing credible, believable castles in the air is a skill.

Living in them — isn’t something to count on.

Re 52,72,77,82,101, and 102:

I first heard the idea of off-planet solar power beamed back to earth with focused microwaves, offered by an emeritus professor of chemistry during a Teach-in at University of Kansas on the first Earth Day so many years ago.

I asked about what seemed like obvious problems for which the professor had no real response. I have been paying attention (off-and-on) ever since and have still not heard reasonable answers.

Briefly: If you are bringing 130 terawatts or 20 terawatts down through the atmosphere to one or ten thousand antenna(e), how big do the antennae need to be (which will determine the photon flux density coming through the atmosphere)? As the photon flux density decreases, the cost of the antennae increase. How will the birds, bats, and people flying through the beam feel about it? Will the microwaves interact with moisture (or other components of the atmosphere)? What will be the meteorological consequences of steady state heating of one or ten thousands columns of atmosphere — dust devils, standing or wandering tornadoes, something else? If you move the antennae to the polar regions to minimize heating of water vapor in the atmosphere, how will the antennae and the transmission grid feel about solar storms and what sort of transmission network would you need to move the electricity to where it is needed?

Perhaps other RC readers can point me toward sensible answers to these questions.

Best regards.

Jim Dukelow