There is a lot of talk around about why science isn’t being done on blogs. It can happen though, and sometimes blog posts can even end up as (part of) a real Science paper. However, the process is non-trivial and the relatively small number of examples of such a transition demonstrate clearly why blog science is not going to replace the peer-reviewed literature any time soon.

Way back in April 2005, I wrote a post on RC on the role of water vapour in the greenhouse effect and why it is considered a feedback and not a forcing in the IPCC sense. It was a basic enough exposition, and in lieu of finding a comprehensive paper on the components of the atmospheric greenhouse effect, I did a few very simple (even simplistic) GCM experiments to show what I was talking about. The bottom line was that CO2 was indeed an important contributor to the present day greenhouse effect, and depending on how you calculated the percentage, could account for between 9 and 26% of the effect.

This proved useful, and soon the page was being quoted quite widely. But the calculations were not very sophisticated and I started to be concerned that they were being given more credibility than they deserved – not that they were necessarily wrong (they weren’t), but because a blog post doesn’t give enough context. For instance, some people incorrectly thought that the range 9-26% was the uncertainty in the calculation, rather than two different conceptual estimates. So I started to look for ‘proper’ references for these kinds of calculations.

I had already seen a few papers that calculated the importance of water vapour, CO2 and clouds for a one-dimensional standard ‘profile’ (Ramanathan and Coakley, 1978 for instance), and I was pointed to a section in Kiehl and Trenberth (1997) that turns out to be the most useful reference. They too had used a single ‘typical’ profile. Both of these references (and a few others – like Ray Pierrehumbert’s 2007 paper which used the NCEP global distribution of water vapour and temperature) generally calculated the importance of CO2 in one of two ways – either by looking at what happened when you removed CO2, or by looking at what happened when only CO2 was operating (though rarely both) (because of the spectral overlaps between the different absorbers, the second number is always larger than the first). Invariably, the treatment of clouds was highly simplified or neglected.

What I didn’t find was any justification in the literature for the most widely quoted ‘contrarian’ view of the issue that CO2 was ‘only 2%’ of the effect. I traced this back to a book review that Lindzen wrote about the first IPCC report, but never found any actual reasoning in support of this.

So in putting together a real paper there were a number of necessary steps that went beyond what was appropriate for a blog post. First, the previous literature had to be collated and their results reported in a consistent way. Second, there were a number of differences between the more serious calculations done for the paper and the calculations done casually for the blog. We used a longer period of time (a full annual cycle rather than a single time step) to avoid a bias towards a particular part of the year. Then we rechecked that the radiation code was still giving good results at very low CO2 levels…. and it turned out that it wasn’t – and so we needed to update the code via comparisons with a more complete line-by-line model so that all the tests we were doing were within the validated range of the radiative-transfer code. Finally, we did many more tests – more combinations, different baselines – to try and ensure that the results were robust.

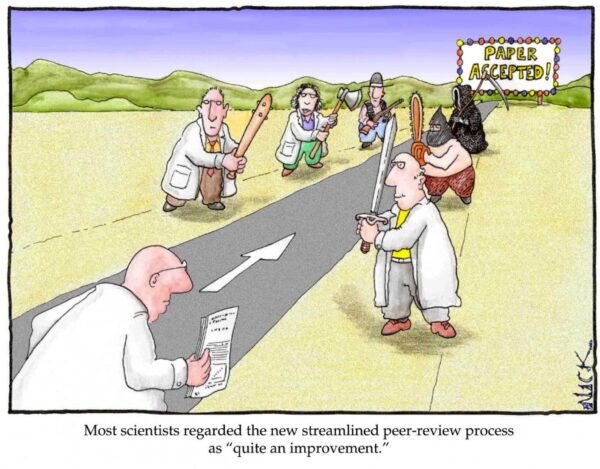

When it came time to submit the paper, we first tried pitching it to BAMS as a popular science piece that would try and explain the concept and clear the air (so to speak). However, for various reasons this didn’t work out (two rounds of unsatisfying reviews). I’d say it was mainly due to the draft not really being pitched at the right level for BAMS. One amusing aspect of the process was that one of the referees initially suggested that our paper wasn’t necessary because it was common knowledge that the attribution to CO2 was between 9 and 26% (sound familiar?). As it turns out, they were reading a page from UCAR which was quoting (without attribution!) from my original blog post.

There was one other interesting (and highly critical) review which objected to the criticism of Lindzen’s 1991 comment, though it is perhaps worth noting that they considered the 1991 comment to be ‘formally incorrect’.

After a period in which I was a little tired of the whole exercise (it happens), we then submitted the paper to JGR, where it had an easier passage. At the same time, the simulations we had done for the paper were also used as part of a broader paper that Andy Lacis wanted to put together for Science. Both these papers appeared in October 2010 – some five years after the initial post, 3 and a half years after the first journal submission, 5 rewrites and 11 reviews.

So why bother to turn ideas from blog posts into real papers? Well, first off, you get to do a much more thorough job. You have the time and space to check multiple variations of the method, and you can take the time to do a proper literature review. And because you have put more effort into it, it is rightly seen as more credible. It’s worth noting that in our case the paper benefited from comments from all reviewers (even the very critical one) – language was tightened up, a broader literature search was done, concepts were clarified and many of the additional issues raised were dealt with.

In turn, the more credible work on the topic forms a stable point around which to craft a critique (if desired), and hopefully provides more of substance to critique (versus a series of blog posts that can be laced with distracting commentary, conceptual errors and moving targets).

To be clear, it is not only the reviews by peers that makes a peer-reviewed paper better than a blog post. Since it is known ahead of time that there is an effort required to get past the peer-review hurdle, the resulting work is usually more reflective, more interesting, more concise and more of a serious contribution – even before it gets to the editor.

Thus when scientists who find themselves criticised in the blogosphere quite often ask their critics to submit their points for peer-review, the point is not to dismiss a critique, but rather to encourage the critics to make the critique as well formulated and a propos as possible. This doesn’t always work of course, but is it nonetheless worthwhile. The alternative, especially for high profile issues, is to try and deal with a multi-headed hydra of critiques that range from the ill-informed to the excellent. Unfortunately, technical commentary does not work well at the ‘speed of blog’ and conversations often take a personal turn (which only rarely happens in the literature).

The many existing critiques of peer review as a system (for instance by Richard Smith, ex-editor of the BMJ, or here, or in the British Academy report), sometimes appear to assume that all papers arrive at the journals fully formed and appropriately written. They don’t. The mere existence of the peer review system elevates the quality of submissions, regardless of who the peer reviewers are or what their biases might be. The evidence for this is in precisely what happens in venues like E&E that have effectively dispensed with substantive peer review for any papers that follow the editor’s political line – you end up with a backwater of poorly presented and incoherent contributions that make no impact on the mainstream scientific literature or conversation. It simply isn’t worth wading through the dross in the hope of finding something interesting.

In the end of course, the science will win out. No single paper is ever the last word on an issue, and there are always new approaches to try and new data to assimilate. But the papers will endure long after the plug has been pulled on a blog. I certainly think that blogs can be of tremendous value in bringing up more context and dispelling the various mis-apprehensions that exist, but as a venue for actually doing science, they cannot replace the peer-reviewed paper – however painful that publishing process might be.

Chris, Raymond #45, the statement is in this video at 47 min 50 sec and on. Lindzen says “approximately two and a half degrees cooler”, presumably Celsius.

Good also to watch Cicerone’s takedown a bit further on… his BS detector is functional.

Ron Taylor, Well, the smart alternative is for people to never place their trust in a single study. Any single study or any single scientist can be and probably will be wrong at some point. However, they will likely be corrected by the next scientist who comes along, or perhaps the one after that. Science is a collective enterprise that produces reliable understanding of the world around us..

I can see Gavin’s arguments on peer review have some sense but would it not be easier if reviewers were not anonymous and we could see their comments more or less as they make them? Then the who said what when arguments could be sidelined.

A further issue concerns the psychological dispositions of reviewed and reviewer. What Gavin calls Science is underpinned with cultural attitudes – this is particularly true in Climate Science. Seeing these hidden discussions will help to this uncover this underpinning (just a little).

But my personal beef is that the brand name “peer review” is a weapon to shut out other views. It becomes a vehicle for what J.K Galbraith called conventional wisdom. I know several peer reviewed articles I distrust but there seems to be little opportunity for the outsider to criticise and have the criticisms answered.

This may be embarrassingly self-centred but, as an outsider, I would like an answer to a question that some may have noticed me ask before: Is the Trillion Tonne Scenario of Allen et. al and Pierrehumbert et.al. seriously flawed because the computer simulations had missing feedbacks? Does this mean that climate change is rather more urgent that even you good guys think?

(See. “Climate change underestimated?” http://www.ccq.org.uk/?p=266)

Gavin,

Thanks for a thoughtful and measured commentary. One thing that I think worth noting is the relatively long time delays in peer review (versus blog exchanges) usually (not always!) give people a chance to calm down before writing something influenced by anger or frustration. “Never write something when you are angry” is I think very prudent advice… but often difficult advice to follow in practice. Things written in anger usually lead to misunderstandings, recrimination, and worse.

“but in non-refereed circles and hearings he never even gives the impression of uncertainty,”

Morgan & Keith published an expert elicitation of climate sensitivity estimates and uncertainty ranges in 1995: Lindzen was among the participants. While the various estimates are not labeled, it is pretty obvious which one is Lindzen’s: “expert 5” had a best guess climate sensitivity of 0.3 with an uncertainty std dev of 0.2: the range of other experts for mean was 1.9 to 4.7, with std. devs of 0.86 to 5.4. So Lindzen, um, “expert 5” had a best guess that was a factor of SIX less than the 2nd lowest estimate, and even worse, had a certainty about his guess a factor of FOUR more certain than the next most certain estimate. Lindzen is certain that he is right and everyone else is wrong to an extent that is (IMO) not appropriate for a scientist.

(Note also that a follow-up study, http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2010/06/24/0908906107.full.pdf, found that the lowest central estimate in the new study was 2.8 degrees. Of the four experts included in both studies, including the former 1.9 that was the lowest of the 1995 estimates outside of expert 5, all increased their central estimate, but their uncertainty bounds largely stayed the same size)

-M

Geoff Beacon,

Science ain’t broke. Don’t try to fix it.

Nobody is excluded. If you have something worth saying, investigate it, learn about it and submit it. If you cannot be bothered to put in the time to learn about it sufficiently to talk about it on equal terms with the professionals, then why should the professionals take you seriously?

It stands to reason that the people who are most interested in a field will have the best understanding of it. Interest is guaged by publication.

> see their comments more or less as they make them?

Because nothing facilitates clear, considered, reflective thinking like having anonymous critics looking over your shoulder blogging their complaints about your progress as you write every word.

You go first. Get one of those virtual network applications and make your machine publicly available.

I don’t think so. Anonymous reviews allow the reviewer to be robust, and avoids the issue that is the defining feature of the O’Donnell nonsense (i.e. a circus of public mischief making). Best to keep the personalities out of the peer review process and allow considered scientific issues to play out, refereed by the editor. “Who said what arguments” are pretty boring, and it’s astonishing how many people feel the need to stick their noses into stuff that isn’t really their business. Imagine the chaos that would ensue if the O’Donnell fuss was multiplied 10,000-fold across the internet as reviewers, reviewees and their assorted cheerleaders engaged in serial hissy-fits. In fact, non-anonymous reviewing is likely to promote the “conventional wisdom” that you remark on.

Since the aim is to promote and facilitate the dissemination and archiving of quality science, the psychological dispositions of the participants are not that interesting (from a scientific point of view, however fascinating from a phil/sci POV). The role of “cultural attitudes” is overestimated in my opinion. The aim is to get quality science into the scientific literature – that’s pretty much what happens, yes? It may not be easy, but why should it be?

I just don’t agree with that. Anything publishable can be published somewhere. It would be easy to list a selection of truly dismal papers in climate science that made it into the peer-reviewed literature. If all else fails and one really feels the need to publish “other views” there are outlets for this (e.g. a journal called Energy and Environment is available for publishing scientifically-deficient “other views” in climate science). If you want to criticise a paper published in the peer-reviewed literature you can always send a critique to the editor. On the other hand if the paper is particularly bad you should check that no-one else has already critiqued it (Google for citations). And if you think it’s bad and no one has bothered to cite it, then it’s really not worth bothering with -you may be observing a sad example of a paper failing post-publication peer review, through scientific disinterest….

For “seeing their comments more or less as they make them”, watch some of the climate related subjects on Wikipedia, including the revert histories and un-hidden “discussion” pages. ;)

Hi Geoff (#50), you bring up a good point that really has to do with the limits of the current state science & tech to do sciene, and the need for scientists to avoid the FALSE POSITIVE of making untrue claims. They cannot afford to be the boy who called wolf when there wasn’t any wolf (even though they know there are wolves out there in the forest); they need to protect their reputation & even the reputation of science itself (as has become so clear in recent years). Hansen has referred to this as “scientific reticence.”

In other words, peer-review is pretty good for spelling out what scientists can quantify and be pretty sure of, but not the unquantifiable variables and their impacts — the known unknowns. We know there’s methane down there in the permafrost & ocean hydrates, which we know is a 23 times more powerful forcing then CO2, and scientists are making ever better estimates about how much there is, and I suppose they could tell how much warming would be entailed if all that methane and CO2 were to be released, even if they cannot easily quantify the varying rates at which it will be released over the next 50 years. Time is really important since CH4 is only in the atmosphere about 10 years — fast release (when the effect is grossly compounded) is much more dangerous than slow release — see https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2005/12/methane-hydrates-and-global-warming . The problem is this is all at a very local spatial frame re the warming in those places(we do know at least that heat melts ice :)) and has to do with time & amount of warming, and amount of release. I’m thinking this is just too difficult (if not impossible) to be quantified for the entire arctic, at least as science goes right now. And if it cannot be quantified & put into some equation in a multivariable dynamic way, it cannot be coupled into the other models that are fairly reliable (tested backwards against existing data).

Another thing that might have to be considered, if and when science can quantify all these variables & put them into an equation, is how global warming might be making more frequent the negative arctic oscillations that bring killing frosts down to my subtropcial garden in S. Texas, while making some areas in the arctic a lot warming (see http://esrl.noaa.gov/psd/map/images/rnl/sfctmpmer_30a.rnl.gif and https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2010/12/cold-winter-in-a-world-of-warming )

I suppose a qualitative article about these known but unquantifiables would be okay, but it would leave too much room for speculation in one direction or the other — which is okay for anthropology (my field), bec who really cares about tribal peoples in some nearly inaccessible jungle. If we did care we wouldn’t be killing them off thru resources extraction, pollution, and global warming. But since some people have very strong stakes (monetary, political, personal, ????) in downplaying and disproving ACC, a qualitative article would be ripped to shreds, if not by legitimate reticent scientists, then by the denialists.

That is why it is also good to read books written by respected scientists who have a long list of peer-reviewed publications, like Hansen and his STORMS OF MY GRANDCHILDREN. Books give a scientist more freedom to address these known unknowns. Hansen has a very good holistic grasp of the issue from a paleoclimatology, geological, current climatology, physics, etc perspective, plus he is an expert on Venus and its history & atmosphere.

We as laypersons and grandparents would be striving to avoid the FALSE NEGATIVE of failing to mitigate a true problem. We don’t need high confidence in a problem to address it….we buy lots of insurance on the remote possibility our home will burn to a crisp. Peer-review seems a tedious and time-wasting process, sometimes taking even 5 years or more, with caveat-filled results that omit the known unknowns. Imagine waiting 5 years going through such a process to buy home insurance. And wouldn’t you know it, the hurricane demolishes the home in 4 years 11 months, a month just before the policy goes into effect.

Ray @50

Good to discuss things with you again.

“Science ain’t broke. Don’t try to fix it.”

Could you mean “The current scientific bureaucracy works very well”?

I’m not discussing Science as such but it would be interesting to know your favourite author on scientific method: Karl Popper, Paul Feyerabend, Thomas Kuhn, RB Braithwaite, Imre Lakatos? You might even consider Ludwig Wittgenstein. I warm to the ideas of Lakatos but Feyerabend was much more fun.

I’m actually interested in how we might have a rational basis for our decisions even if they are self destructive or self serving.

Of course, I don’t know as much climate science as the professionals – although many have been kind enough to meet, talk and correspond with me. I think I know enough to ask the question of the proponents of the Trillion Tonne Scenario “Do you know how much the feedback effects that are missing from the climate models affect the results?” That seems a perfectly understandable question to me. If it can’t be answered we should know because, with the UK Government, it seems to be embedded in their policies.

In what way would you say that my question is misinformed?

Maybe Jim Bouldin should read this, about the alarming increases in tree mortality, written by Dr. Franklin of UW:

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/323/5913/521.abstract

Mortality increases are also verified by PNW. Causes are not known with precision, but logging and ozone could clearly be important factors. Foresters are not professionally or politically equipped to make those determinations.

Gavin and Eric, forestry is not like other disciplines.

[Response: Maybe Mike Roddy would realize, if he read the paper he refers to, and RC, that I wrote an RC article specifically about it two years ago when it came out, that the authors took real pains in their experimental design to exclude exactly the kinds of hand-waving causes that he mentions, and that Jerry Franklin is not the lead author of that paper. Maybe he should also not use the term “alarming” for the small percentage increases in background mortality that the authors detected over a relatively short period of time, disparage the knowledge of professional foresters in one fell swoop, and should realize that this entire subject is off topic and has been thus moved to the open thread.–Jim]

Gavin, thanks for the posting on this subject. With the talk of “post normal science” (or whatever it’s called) I think it doesn’t do any harm explaining more clearly the advantages of peer review.

I wonder if it would be possible to give further examples of how original work has been made clearer or “improved” within the peer-review process. Or, this might be a bit cheeky, work that peer-review caused the author to withdraw the study? As other’s have put more eloquently, peer review seems to produce much higher signal-to-noise information than blogs tend to.

[Response: Sure. I’d say 90% of my papers have been significantly improved by peer-review – there is almost always something that can be made clearer or more convincing or context that can usefully be added. I’ve also had perhaps 1 or 2 papers that got rejected and never got pursued (out of 80 or so published). Perhaps a dozen papers ended up in different journals than the one first submitted to. Examples of all these kinds of things can be seen at the open review journals (ACP, Climates of the Past, Geoscientific Model Development etc.) – papers that get rejected at the discussion stage, useful reviews that made a reasonable paper, a good one etc. – gavin]

Dale, the first clue that an attacker is off-base is the use of ad hominem.

A more general comment: Our public schools need to do a better job of teaching everyone, not just (future) scientists, how to evaluate what they see and read. I encounter people every day who accept propaganda at face value, and who are completely unable to distinguish specious arguments from real science.

I’m indebted to a high school physics teacher who started out telling his physics classes, “Don’t believe anything you read, and only half of what you see.”

Chris @58

We haven’t got the time. Is the editor conservative or liberal? I’ve read research claiming conservatives change their minds too little and liberals too much. And there is more in the background than psychological profile.

I’d like to know if Linzen or Hansen said it

That could be a problem but isn’t the future of the world everybody’s business? There should be a way for me to ask my perfectly reasonable question. Can you or anyone tell me why it is not reasonable?

Is it “quality science” if it cannot respond to simple questions? I have heard a top notch climate scientist categorise fellow scientists as “left” or “right” in their scientific attitude. I reckoned the descriptions were accurate.

I don’t want to publish.

I don’t want a Ph.D. in Climate Science.

I just want a simple question answered.

“Do the authors know how much the feedback effects that are missing from the climate models affect the results of the Trillion Tonne Scenario?”

Hi Lynne (#60)

Good post. I will read it carefully.

M#55,

I believe (not certain, but believe) that Lindzen has suggested a sensitivity of ~0.3 degrees per watt, or equivalent to ~1.15 C per doubling of CO2 concentration. Might there be some confusion about units?

raypierre–

About Richard Lindzen’s quote, Martin Vermeer gave the link I was referring to in his comment #51 starting at about 47 min in.

Lindzen never caveated his number so I’m going to assume he is including feedbacks, but even with just a straight Stefan-Boltzmann sensitivity it’s still a substantial underestimate. No one else really knew the answer though, and it would have been a good point to bring up triggering a snowball.

In any event, for people interested in this stuff, it’s a good set of testimonies overall. Richard Alley gives the best talk and is a good example of how to communicate to different audiences.

The philosophy of science (POS) questions on methodology are interesting. One might say that the side shows of attempted misinformation that accompany areas of science that potentially impact political and economic interests are Fayerabendian in the broad sense that we allow inclusion of that stuff into what we mean by the process of doing science (Fayerabend would probably say we should, and to the extent that the circus does influence a little how scientists in those particular research areas get on with their day jobs, perhaps it’s reasonable to do so).

And there are Fayerabendian elements in the normal progression of scientific knowledge although science is rather structured these days and perhaps Fayerabend’s ideas are a little less useful than in the past.

I like to think that science at the coalface has a strong Furykian element (that’s Jim Furyk)! The analogy equates the publication of a scientific paper with getting the golf club square and moving sweetly through the ball at impact. It doesn’t matter too much what goes before one gets the club there (see Jim Furyk’s golf swing!); likewise it doesn’t matter too much how one arrives at the set of data and its interpretations that constitute the basis of a paper….the bottom line is that the data is correct and the interpretations justifiable to the best abilities of the authors.

In my opinion Kuhn isn’t that useful in considering the progression of contemporary science; if anything the erroneous application of his ideas on paradigms is too often used to attempt point scoring. One of the problems with Kuhn (but not really Kuhn’s problem if you see what I mean) is that one really needs to address Kuhnian POS with an historical perspective. Who’s to say whether at any particular time we are engaging in normal science or are in the process of overturning the prevailing paradigm?

Perhaps Ecclesiastian POS should be brought into the equation too: “…all is vanity…“

“Since it is known ahead of time that there is an effort required to get past the peer-review hurdle, the resulting work is usually more reflective, more interesting, more concise and more of a serious contribution – even before it gets to the editor.”

How true, and how under-appreciated by the promoters of ‘blog science’.

In my view, the two main benefits of peer review are (1) it promotes scholarship, and (2) it provides an authoritative record of scientific effort. The latter is critically important for the working scientist.

So then…

If, in the course of telling someone who disagrees with you to publish their arguments in the peer-review first, is it possible that you may actually find yourself in the position of being asked to review that same rebuttal that’s trying to be published? If so, is it possible that you can recommend the editor reject this same paper?

[Response: Of course. And the editor is free to ignore anything I say – especially if it conflicts with the other reviewers. In dealing with comments on a few of my papers, it has been clear (to me at least) that the comment had nothing very much to add, or was greatly deficient in some way – in those cases, I’ve said so plainly. Some of those comments were published, others were not – but in every case it is the editor’s decision, not the reviewer’s. Editors are not stupid, and they know they need to balance multiple interests at once. On the whole they do it well, but there are clearly some occasions when they lose the ball (the Soon/Baliunas fiasco, a couple of comments James Annan was involved with, etc). – gavin]

Mike Roddy @62 citing van Mantgem et al., suggests that logging and ozone may be important factors in increased tree mortality in the Western U.S. Actually, the authors of that paper observe that “the available evidence is inconsistent with major roles for two possible exogenous causes: forest fragmentation and air pollution.”

[Response: Correct. Thanks for paying attention Rick.–Jim]

Geoff Beacon @64

Come on. We’ve got plenty of time for peer review. Mostly it takes between 3-9 months submission to final acceptance, occasionally there are a few horror stories. But what’s your rush!? The aim is to get good quality science published. The idea that we haven’t got time to “allow considered scientific issues to play out, refereed by the editor”, doesn’t make any sense. Papers are submitted and good stuff get’s published…it seems to work!

The “consevastive”/”liberal” comment is astonishing to me. If an editor(who is usually a subeditor or associate editor) is perceived by a journal to allow political leanings affect his/her integrity then they’ll likely do something about it. The dreary deFreitas case comes to mind.

Nevertheless, I contend that conservative, liberal, communist,7th day adventisit editors notwithstanding, a good paper will always find a good home in the scientific literature.

Not sure what you mean there Geoff. It’s it’s the Trillion Tonne question in your post 53, then ask away. The point I rasied that you responded to doesn’t affect your ability to ask questions one little bit! My point is about people getting worked up about what reviewers and editors might have said during the peer review process. To my mind that doesn’t matter a jot to the outside world. The point is to get a good paper published.

?

No idea what you mean by that – you’re completely drifting off the point in your responses to my statements. Can you clarify please…

Bob Sphaerica @ 46 Excellent, excellent post. I almost dislike the deniers as much for their misappropriation of the term sceptic, as I do for their mangling of the scientific method…

Bob S at 46 Excellent, excellent post. I almost dislike the deniers as much for their misappropriation of the word ‘sceptic’, as I do for their mangling of the scientific method.

> know how much the feedback effects that are missing …?

Geoff, I was a cave guide, long ago. We often got asked “How many miles of unexplored passages are there in this cave?”

What can you tell someone who thinks that’s a perfectly reasonable question?

[Response: Like the rafting customers who ask “who put all those rocks in the river?”, just about anything will do.–Jim]

Pat Cassen #70 I would add a third: peer review ensures that science remains a collaborative effort, and even provides a mechanism by which arch rivals, in the face of outright hostility, may contribute to one anothers work.

“This is the whole point. Lindzen (or a blogger) gets up and makes vague, unsupported statements, and you unquestioningly accept them. You even go beyond that, giving him the benefit of the doubt, defending his position, struggling to find ways to qualify what he said to make his position tenable.”

I am not accepting his unsupported statements. But I AM giving him the benefit of the doubt until such time as I can see he is wrong. If I can see how he *might* be right then until such time as I can see he is definitely wrong I wont write him off.

You should be prepared to do the same. Maybe you’ve seen the quote in full within context and have a better understanding but if you haven’t maybe you need to reconsider your position on judging “blogged” arguments too.

[Response: An observer might conclude that you are being extremely irrational. We have provided you with a whole paper of such calculations, references to half a dozen other works supporting the same conclusion (that CO2 is a significant part of the present day greenhouse effect). Lindzen has provided nothing but a claim (with no backup rationale or theory) and you think that we should give him the benefit of the doubt. Curious. Should he never say anything else on this topic (very likely), one presumes you would therefore support your ‘oh it’s all so uncertain’ refrain forever, regardless of how much other work supports the claim made here. The only explanation of this is that you favor his conclusion for some non-scientific reason, no? At which point, one might ask why you are bothering to discuss this if no amount of actual science is going to convince you even of something as relatively uncontroversial as this. – gavin]

Chris, Feyerabend is less than worthless. He didn’t understand science. He didn’t understand philosophy. He didn’t understand anthropology, and all he cared about was being controversial. I deplore book burning, but in the case of Feyerabend’s work, I’d make an exception.

Geoff Beacon,

Feyerabend was an idiot, as I’ve noted above. Popper has some merit, but his ideas don’t apply in every situation. I think Ed Jaynes Bayesian ideas are quite interesting and useful. Kuhn’s work applies to only a very tiny portion of scientific history. I have no use for Wittgenstein.

Basically, I think you learn the philosophy of science–if you are to learn it at all–by doing science. I think that without the experience of doing science, it can be very difficult for an outsider to fully grasp how the scientific method fits together and why the scientific community functions the way it does.

[Response: Very much agreed–nearly impossible in fact. Lots more to it than meets the eye, and tough to explain.–Jim]

Nobody likes bureaucracy. It’s what you put up with so that you can do science. However, there are very good reasons why science is inherently a conservative methodology. Science cares about being right, but it also cares about how it may be wrong. Some errors are more serious than others. One example is that science prefers to err on the side of the simpler model. If the simplification is seriously wrong, nature has a way of telling us.

I think that the questions you are asking are not so much science as they are at the boundary between science and engineering/risk mitigation. Even the definitions of conservatism are different in these two fields. Don’t mix them up.

Ray Ladbury @79 — Even Wittgenstein had no use for Wittgenstein. He repudiated the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

“An observer might conclude that you are being extremely irrational. We have provided you with a whole paper of such calculations, references to half a dozen other works supporting the same conclusion (that CO2 is a significant part of the present day greenhouse effect). Lindzen has provided nothing but a claim (with no backup rationale or theory)”

You see Gavin, this is the problem and its right on topic. What you have provided is precisely nothing. Another poster provided a one line quote to back up the article’s claim and others have provided clues as to what Lindzen might be thinking from related discussion. Noone has provided the context that the quote was made within.

This is PRECISELY the lesson that MUST be learned here. When you dont have sufficient evidence to properly understand what someone says in a blog posting, then you can have an opinion one way or the other but thats all it is…a private opinion.

If you’re not sure then you should then seek clarification and in this case none has been forthcoming. The result of going off half cocked has been made apparent recently.

You want me to accept what you say at face value with regards the specific quote in question and I simply wont do it. Your assessment of what I believe is way off base and is yet another example of misjudgement but your reasoning for making that discrediting assessment is perfectly clear.

[Response: Huh? I showed you his House testimony. Did you read it? Full context – and no support. The QJMRS reference is unfortunately not freely online but there is no more context in that either (it’s in a book review!). Versus, Schmidt et al (2010), Ramanathan and Coakley (1987), Kiehl and Trenberth (1997), Pierrehumbert et al (2006). I can’t make you read anything, but for you to claim that it’s just my word against Lindzen is idiosyncratic in the extreme. There is no more to Lindzen’s statement – so there is nothing more to show you. – gavin]

> who put all those rocks in the river?

Same answer as “where did all the salmon go” — first hydraulic mining raised the river bed by many feet; bank erosion tumbled boulders in; gravel mining is steadily removing the small stuff lowering the water level; thus the river bed is full of big rocks. Then they dammed the river, withdrew a lot of water, and lowered the flow ….

” I showed you his House testimony. Did you read it?”

Yes I did but its not the context of the quote in his book is it. FYI, I do agree that Lindzen *probably* meant 2% of warming is attributable to ALL the CO2 from the one liner quote but as I said, that’s just an opinion and until I see the context in which it was made I WONT be parading it around for all to see as a blog article.

And if after finding all the facts supported my conclusion, I’d make sure I provided in the article both the quote AND context within which it was made to back up my claim.

As it is Gavin, what you’ve done in your article is exactly why blog postings criticising others can go off the rails.

There are much better examples than this but perhaps not for this thread at this time.

TimTheToolMan @82 — Calm down and take the time to study “The Discovery of Global Warming” by Spencer Weart:

http://www.aip.org/history/climate/index.html

Oh…and NOW I see that you’ve gone back and added a comment to an earlier post that I hadn’t seen.

So with this in mind, THAT is the quote you should have used (not as another poster suggested, the one from the book) and you should have quoted it in your article so there are no misunderstandings and nobody has to take your word at face value.

Reference Enneagram of Personality/Psychology http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enneagram_of_Personality

The university science departments favor type 6 Loyalist over type 5 Investigator scientists. As a 5 with a 4 wing, I want to find the truth, but I have a hard time caring to prove it to you.

Reference Enneagram of Personality http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enneagram_of_Personality

The university physics departments also favor theorists to the exclusion of experimentalists and inventors. [Inventors are not the same as engineers.] There are many experimentalists in universities because experimentalists outnumber theorists greatly.

How much is the peer review system a personality test?

A long way indeed.

http://wattsupwiththat.com/2011/02/13/a-conversation-with-an-infrared-radiation-expert/#comment-599159

The ole infrared thang by an expert without a physical science degree. hey, anyone can do it, and they do on blogs.

[Response: I’m averse to polluting myself by wading into the sewer of pseudoscience over there, but perhaps somebody with more fortitude would do me the favor of going over there and posting a link to my Physics Today article on infrared radiation. (available at http://geosci.uchicago.edu/~rtp1/papers/publist.html ) Maybe then they’d learn something (though I doubt it). –raypierre]

What is a forcing and what is a feedback is a little confusing. There is some treatment of the subject also in 2005 in Hansen et al. (2005), Efficacy of climate forcings, J. Geophys. Res., 110, D18104

I’ve been looking at it because I am still trying to figure out the meaning of fig. 30 in Hansen’s recent book, ‘Storms of my Grandchildren’ Fig. 30 there corresponds to fig. 25 in the paper but with a different scaling. In the paper efficacy is plotted normalized to the behavior of carbon dioxide at present. But, in the book the normalization of 0.453 C/W/m^2 is removed I think. This is what has been making me scratch my head the most. I understand 0.75 C/W/m^2 as a Charney value and I think I would understand say 0.15 C/W/m^2 as a carbon dioxide only value but I’m not getting where 0.463 really comes from. More reading to do.

Since the unforced variations thread is closed, I’ll mention here that raypierre appeared to have given an incorrect answer in #254. The runaway concept was discussed in Hansen et al. (2005) where raypierre claims it was not in any paper. I’d already corrected raypierre in #259 on his misconception that Hansen was only concerned about burning coal. https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2011/02/unforced-variations-feb-2011/comment-page-6/#comment-199705

If anyone gets the 0.463 C/W/m^2 normalization for fig. 25 in Hansen et al. (2005) (Gavin was a co-author) in the context of the current discussion I’d appreciate a hint.

[Response: To a great extent, what is a forcing and what is a feedback depends on the time scale involved, and what you are trying to model explicitly, vs. estimating from observations. Except perhaps for the stratosphere, water vapor and clouds would almost invariably be considered feedbacks, since they adjust so quickly to changes in temperature and winds introduced by various forcings. In other cases, it can go either way, depending on the problem. For example, when we run a GCM without a carbon cycle, and specify the CO2 concentration over the next 200 years (say), then CO2 is a forcing. If, instead, we run a model with a carbon cycle and specify emissions rather than concentrations, then the CO2 taken up or emitted by the land, or the changes in CO2 taken up by the ocean, are all feedbacks on the CO2 emitted by anthropogenic activity (which are the forcing in this case). If we are trying to understand the climate of the Last Glacial Maximum and specify ice sheets to be where geology tells us they actually were, then they are a forcing. If we specify other climate forcings but instead compute the ice sheets using an ice sheet model, then the ice sheets are a feedback. For that matter, in glacial-interglacial cycles, CO2 is a forcing if we specify it using the Vostok record, but it is a feedback on Milankovic forcing if we try to compute it using a carbon cycle model. –raypierre]

[Response: Regarding the runaway, I will look at the 2005 paper and see what Hansen argues about the runaway there, but all the extensive arguments I already gave for a Venus Syndrome still apply so let’s not start that argument over again. Anybody who wants to review that can go look at the Unforced Variations thread. The reference to Hansen’s book in the comment you cite was mostly to address some other commenter’s query about what statement by Hansen was under discussion. And before you get so fussed about correcting my “misconceptions,” as I said before, it doesn’t matter if Hansen is getting his carbon from burning coal, from clathrate releases, or terrestrial carbon cycle feedbacks; you still don’t trigger a runaway greenhouse by increasing atmospheric CO2, so long as you are in an orbit that is getting less than the threshold solar radiation needed to sustain a runaway. –raypierre]

[Response: OK, I had another look at the 2005 paper, which I hadn’t re-read since Hansen started talking about the Venus Syndrome. There is some incidental mention of the runaway greenhouse phenomenon in general here, but Hansen does not demonstrate a runaway in the model. He only shows an increase in the efficacy of forcing (basically the climate sensitivity) at high temperatures, which is not something I have ever disputed. In particular, I do not find any place in the paper where he argues that the Earth could actually succumb to a Venus type runaway. The closest he comes is the statement, “… there is a hint of the runaway greenhouse at 8 XCO2.” but I have no idea what he means by “hint” here. Having a “hint” of a runaway greenhouse would be like being just a little bit pregnant. In fact, the efficacy diagram shows a rather modest increase in climate sensitivity at the high CO2 end, so I don’t even see a “hint” here myself. He mentions that there are numerical problems in the model that prevent exploration of the very warm regime. (That’s strange, because NCAR and FOAM do fine up to 20% CO2 in the atmosphere and show no indication of running away). –raypierre]

> and NOW I see that you’ve gone back and added a comment

TTTMan: right sidebar, under “…With Inline Responses” — that’s how it works.

Ray Ladbury #80 “Basically, I think you learn the philosophy of science–if you are to learn it at all–by doing science. I think that without the experience of doing science, it can be very difficult for an outsider to fully grasp how the scientific method fits together and why the scientific community functions the way it does.

[Response: Very much agreed–nearly impossible in fact. Lots more to it than meets the eye, and tough to explain.–Jim]

“It has to be experienced to be understood” is true of many disciplines, that is why we have teachers. However, isn’t the scientific method a matter of ethics, not experience? Perhaps you could expand on your statements a bit more, Ray or Jim.

[Response: You phrase that very interestingly, in a way that I have strong agreement with, but which I’m not quite sure you meant to imply (or maybe you did, I don’t know). My first response though, is that there is no such thing as “the” scientific method. Scientific approaches/methods vary widely (very widely!) depending on the exact nature of the question at hand–and the exact nature of the question at hand…varies widely! The idea that there is one single method–or even a small set of methods–is a great misunderstanding. I think even Platt in his famous paper (“Strong Inference” ;1964) may have made that mistake–his points are valid but he seems to have little awareness that a huge chunk of science is non-experimental in nature, which creates all kinds of havoc. This is not to say that there are not definite procedures and strategies to follow in order to acquire discriminating information most efficiently–there are. But those vary with the nature of the problem being addressed. To answer your question: anything goes; do whatever it takes to help you get some additional insight into the nature of the question at hand. It may be acquiring additional (or higher quality) observations, it may be the use of better analytical techniques borrowed from another discipline, it may be getting an entirely new perspective on the problem by reading or talking to others. There are in fact very few set rules. It’s not cookbook–it’s creativity. As for the issue of ethics, if that’s what you really meant, Einstein had a bunch of quotes along those lines. It basically boils down, IMO, to caring and honesty. If you don’t have those two things, forget it.–Jim]

OAB, I am convinced that morality has much less to do with it than does methodology or even curiosity. In science, the closest we have to a moral stricture is an agreement to be bound by the evidence. However, this isn’t really much of a restriction. You don’t become a scientist without being passionate about understanding your object of study. And since any deviation from the evidence will decrease our understanding rather than increase it, falsifying or denying evidence is actually a mortal sin to a scientist. And of course, there is the 100% certainty that if you falsify data–especially data with any importance, YOU WILL GET CAUGHT. Nature won’t cover for you. She always gives the same answers when you ask the same questions (properly phrased).

There are some scientists who are right bastards, and pretty much all of us have our moments. In real life, I wouldn’t trust them further than I could throw the. If they said it was sunny, I’d take an umbrella. However, if they are good researchers, I’ll pay attention to what they say in their papers.

The most remarkable thing about the scientific method is not that it somehow makes us better people, but it works with people as they are, with all their flaws to yield reliable understanding of the world around us.

Chris @73

“Had we but time enough and time, dear Chris, were no crime We would sit down, and think which way To Kurl and pass our long love’s day.” Have you seen today’s Arctic sea-ice extent?

Even Bing found me this: Liberal & Conservative Brain Differences?.

But not get an answer.

Here may be learning what each of us means by “quality science” but it’s clearly a valuable brand worth fighting over.

Hank (#76)

Very interesting, exploring caves – but we’re in a dark cave and need the breeze on the candle to show us the way out. We don’t know there is a way out for certain but we must make a good guess. I like what Lynn (#60) said

Somehow “scientific reticence” must be overcome. Answering my question would be a start.

No it won’t. If you can’t make your best guess then you are failing us. If I had my way you would be paid half your salary in Intrade contracts on climate change. You could choose the contracts. Then we might know.

Ray Ladbury @80

I don’t think Feyerabend would have objected to the gist of that but I only attended a couple of his lectures. I bought “Against Method” but didn’t complete it. I find it boring to read people with whom I am in agreement.

“outsider”! What makes an outsider. Have you seen “Never let me go?” yet.

Should we say “Scientists care about how they may be wrong.”? Then we don’t have to ask the question “What is this thing called Science?” (The title of a nice little book by Alan Chalmers.)

Given the current political/intellectual climate, I can sympathise with scientists who are under pressure but if the deniers get answered why can’t I?

Oh yes – “outsider”.

“. . . huge chunk of science is non-experimental in nature. . .”

Yes, this becomes part of the denialist canon in some cases, where the model of experimental physics (laboratory subset) becomes reified as the sum total of ‘true science.’ Thus, the vast body of observational data of what the atmosphere actually does can be, well, denied, since what happens in the lab is [all of] science.

This seldom seems to stop this subspecies of denier from objecting at other times that while lab measurements do show that GHGs act as GHGs, that may not be the case in the atmosphere. . . go figure.

Very nice Geoff, but peer-review progresses with a robust steady beat and quality research pings its way steadily into the scientific literature. Everyone does do their job pretty well (and who would ask for perfection when good enough is fit for purpose.)

Yes, that’s interesting. Does it significantly impact the peer review process in the physical sciences? I doubt it (there are a tiny number of examples where political points of view have affected peer-review (e.g. google DeFreitas/Baliunas/Soon). Ultimately it’s all about the evidence, nd good evidence is difficult to argue against (outside of blogs) (One might imagine that some fields may be more susceptible to reviewers political leanings – e.g. papers on racial differences in cognitive abilities or relationships between societal wealth disparities and adverse social outcomes – that sort of thing!)

Of course one could argue about this at tedious length but the proof is in the pudding – good papers do get published, and even mediocre papers (and sometimes downright dismal papers) find their way into the scientific literature – it works!

Sounds like you’re not trying hard enough then. One can’t expect to call out and expect some kind expert to drop the answer into your lap (an image of an imploring baby bird in its nest with it’s mouth wide open comes to mind!). I don’t know the particular answer to your question…why not email it to someone you think might know…or do a scientific literature search. It depends one one’s level of interest the effort one takes to seek answers to questions-No?

Well you’re certainly learning what I mean by it since I’ve given some insight on that in my posts. It’s not clear in your case.

In fact I think we can make fairly objective assessment of what is and isn’t “quality science”. That’s something we could discuss…

Geoff,

No. Had I meant that scientists care, I would have said so. The scientific method is structured so as to produce more false negatives than false positives. That is, a statement may be true, but science will wait until the evidence is pretty well incontrovertible before accepting it as true. There is a whole vocabulary scientists use in cases like this–words like suggestive, indicative, and the all-purpose perhaps. This isn’t being wishy-washy. It is as far as the evidence will let you go. Your questions on the trillion-tonne scenario are interesting and they are no doubt the subject of active inquiry, but we don’t have any definitive answers just yet. This is one of the things Feyerabend was just flat-assed wrong about: It’s all about method.

That does not change the situation for policy, though. A climate sensitivity of 3 degrees per doubling–the favored value–certainly poses significant enough concerns to warrant immediate, effective action. Even the lower 90% CL bound of 2 degrees per doubling is a concern. It is only on the question of what would be effective that the exact value of sensitivity becomes important. This is where the engineering comes in to ask questions like: “How bad can it be?” “What actions must we take to mitigate the threats if they are that bad?” I hope you can see that this is related to, but different from the science.

The other thing we have to realize is that climate change is merely one of many interrelated and intertwined threats we face–all of which we must resolve if we are to reach the ultimate goal of sustainability. We must reduce population. Key to that is the raising of living standards and promotion of education, especially of women. Key to that is support of international development. We must negotiate the upcoming cresting of global population without irreversibly damaging the carrying capacity of the planet–and that includes its climate. We must develop sustainable energy resources. We must develop an economy that extracts and uses resources more sustainably. And ultimately, we must develop an economy that remains stable despite a declining and so inevitably aging population. If we fail on any of these tasks, human civilization may be at risk, and perhaps ultimately even human survival.

So, Geoff, the only thing that identifies you as an outsider is the fact that you seem to think the lack of an answer relates to something other than the inherent uncertainty of that answer.

raypierre (#89),

Thanks for the response. I think your use of the term runaway and Hansen’s use differ. There are a couple of numbers in Kasting’s abstract: 1.4 and 1.1 times the current solar constant. The first gives a runaway in your sense where the oceans evaporate and remain as the atmosphere for 100 million years. The second leads to a somewhat higher partial pressure of water vapor than at present and a sufficiently damp stratosphere that the oceans would be lost withing 4 billion years. Hansen accepts this later value as a runaway. It is not clear that Venus ever ran away in your sense. If it ever had oceans perhaps it did not and rather followed the path Hansen had in mind. I think you should grant Hansen his use of the term or at least grant him the use of the term Venus Syndrome and meet him on his ground. He may be confusing the two a little, but he has stated what ‘threshold’ he is discussing in his book.

After you left the discussion on Unforced Variations I was able to inventory enough organic carbon to make his argument that the equivalent 1.1 times the current solar constant could be attained through fossil fuel burnings and feedbacks plausible (#307). So, he can get to the point where the Earth’s water is vulnerable to loss. And, that is what he means by runaway so far as I can tell from his book.

That is why I proposed here a couple of years ago and again more recently in the Friday Roundup, that is comes down to a matter of a race between hydrogen loss to space and removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by weathering of silicate rock. Most likely, weathering wins that race. But, you have to follow Hansen a fair distance, I think, before this flaw in his argument becomes apparent. It would be incorrect to dismiss him on semantics alone, or limit organic carbon inventories to coal only. And, it would be good to nail down weathering behavior with more sophisticated models.

[Response: We’ve been through most of this before, but I’m tired of arguing the point with you. You’re still confused about the situation for Earth and AGW, but the quality of your confusion is at least improving. The remarks below, pertaining to the broader questions of true “dry” runaway and planetary evolution, are more pertinent. The question hinges on the time evolution of extreme ultraviolet flux, but also on whether you can get rid of the oxygen produced by photolyzing water vapor. But the broader planetary issues are rather off-topic for the present discussion. What would be on-topic would be the way water vapor tends to increase the climate sensitivity as you go to warmer conditions (e.g. at very high CO2). That is definitely something worth thinking about, even if we leave aside the question of water loss in warm climates. Even for fixed relative humidity, and even without taking clouds into account, the OLR vs temperature slope (reciprocal of climate sensitivity) weakens as you go to higher temperatures, and that is indeed related to the fact that there is a runaway threshold “out there,” even if we don’t have enough solar flux to trigger it. That is essentially what Hansen was saying in the 2005 paper, in a somewhat confusing way, and that remark is essentially correct. But to make full sense of what is going on, you’d need to look at the shape of the OLR vs. T curve at high CO2; in the part of the temperature range where CO2 is competitive with water vapor, the presence of CO2 helps maintain high temperatures with the same solar flux we have now, but it can also increase the slope of the curve. People are certainly tired of hearing about my book but, dare I say, there is an illuminating graph of this sort in the real gas section of Chapter 4. –raypierre]

One interesting outcome of this discussion might be the statement that for stars like the Sun and planets with Earth-like gravity and water endowment, a runaway in the sense you mean is nearly impossible. If Venus was formed very close the KI limit, heat from accretion would have kept water in vapor form and oceans would never have existed. Nothing to runaway from with no condensed reservoir. If oceans did exist, then they could escape through a moist stratosphere long before the Sun brightened enough to cause a ‘true’ runaway. Earth will never see a ‘true’ runaway because Hansen’s path to Venus-like conditions will be followed when the Sun brightens by 10% with oceans present throughout almost all of the period of loss of hydrogen to space.

It would be an interesting question to address to know if there are any stars with sufficiently low UV emission (needed to dissociate water vapor) that escape of hydrogen could be delayed long enough for a ‘true’ runaway to occur ever for an Earth-like planet recalling that main sequence evolution is slower at lower luminosity so that reaching 1.4 times the current solar constant would take longer. It may be that water runaway is only relevant to more massive or more water rich plants. Answering this question may be relevant to choices of instrumentation that will be used to study exo-planets.

Ray (raypierre) — on the charts in your paper, can you relate “wavenumber” to something more familiar in a simple way? I’d asked an astronomer a question about some quite old info on the web and got a reply recommending your paper with the warning that students have had trouble with “wavenumber” reading it.

Geoff, again, see the uncertainties in the IPCC work and watch for more.

You are insisting you want more, and you don’t know how to get more, so someone else has to do it. If you’d work on understanding and explaining what we do know to the politicians, they’d be in a position to ask for more — by funding the work.

See Donella Meadows who’s written on sustainability leverage points. People _most_often_ push the wrong way when they identify a leverage point. You’re at one here now. Think and consider please; you are trying to push the scientists. It’s the wrong direction to push, to get the result you want.

[Response: I use wavenumber in units of 1/cm because it’s what infrared spectroscopists most commonly use. The wavenumber is the reciprocal of the wavelength, and if the wavenumber is being measured in 1/cm, then the reciprocal of the wavenumber is the wavelength in cm. Multiply by 10000, then, to get the wavelength in microns. Thus, a wavenumber of 1000/cm is 10 microns wavelength. Because of the dispersion relation for light wavenumber is really just frequency measured in funny units. The frequency in Hz (cycles per second) is c times the wavenumber, where c is the speed of light measured in cm/s . The spectroscopists use of the term “wavenumber” for this entity is indeed confusing, since the more common mathematical use of the term ” wavenumber” would be 2pi divided by wavelength. –raypierre]