Interesting news this weekend. Apparently everything we’ve done in our entire careers is a “MASSIVE lie” (sic) because all of radiative physics, climate history, the instrumental record, modeling and satellite observations turn out to be based on 12 trees in an obscure part of Siberia. Who knew?

Indeed, according to both the National Review and the Daily Telegraph (and who would not trust these sources?), even Al Gore’s use of the stair lift in An Inconvenient Truth was done to highlight cherry-picked tree rings, instead of what everyone thought was the rise in CO2 concentrations in the last 200 years.

Who should we believe? Al Gore with his “facts” and “peer reviewed science” or the practioners of “Blog Science“? Surely, the choice is clear….

More seriously, many of you will have noticed yet more blogarrhea about tree rings this week. The target de jour is a particular compilation of trees (called a chronology in dendro-climatology) that was first put together by two Russians, Hantemirov and Shiyatov, in the late 1990s (and published in 2002). This multi-millennial chronology from Yamal (in northwestern Siberia) was painstakingly collected from hundreds of sub-fossil trees buried in sediment in the river deltas. They used a subset of the 224 trees they found to be long enough and sensitive enough (based on the interannual variability) supplemented by 17 living tree cores to create a “Yamal” climate record.

More seriously, many of you will have noticed yet more blogarrhea about tree rings this week. The target de jour is a particular compilation of trees (called a chronology in dendro-climatology) that was first put together by two Russians, Hantemirov and Shiyatov, in the late 1990s (and published in 2002). This multi-millennial chronology from Yamal (in northwestern Siberia) was painstakingly collected from hundreds of sub-fossil trees buried in sediment in the river deltas. They used a subset of the 224 trees they found to be long enough and sensitive enough (based on the interannual variability) supplemented by 17 living tree cores to create a “Yamal” climate record.

A preliminary set of this data had also been used by Keith Briffa in 2000 (pdf) (processed using a different algorithm than used by H&S for consistency with two other northern high latitude series), to create another “Yamal” record that was designed to improve the representation of long-term climate variability.

Since long climate records with annual resolution are few and far between, it is unsurprising that they get used in climate reconstructions. Different reconstructions have used different methods and have made different selections of source data depending on what was being attempted. The best studies tend to test the robustness of their conclusions by dropping various subsets of data or by excluding whole classes of data (such as tree-rings) in order to see what difference they make so you won’t generally find that too much rides on any one proxy record (despite what you might read elsewhere).

****

So along comes Steve McIntyre, self-styled slayer of hockey sticks, who declares without any evidence whatsoever that Briffa didn’t just reprocess the data from the Russians, but instead supposedly picked through it to give him the signal he wanted. These allegations have been made without any evidence whatsoever.

McIntyre has based his ‘critique’ on a test conducted by randomly adding in one set of data from another location in Yamal that he found on the internet. People have written theses about how to construct tree ring chronologies in order to avoid end-member effects and preserve as much of the climate signal as possible. Curiously no-one has ever suggested simply grabbing one set of data, deleting the trees you have a political objection to and replacing them with another set that you found lying around on the web.

The statement from Keith Briffa clearly describes the background to these studies and categorically refutes McIntyre’s accusations. Does that mean that the existing Yamal chronology is sacrosanct? Not at all – all of the these proxy records are subject to revision with the addition of new (relevant) data and whether the records change significantly as a function of that isn’t going to be clear until it’s done.

What is clear however, is that there is a very predictable pattern to the reaction to these blog posts that has been discussed many times. As we said last time there was such a kerfuffle:

However, there is clearly a latent and deeply felt wish in some sectors for the whole problem of global warming to be reduced to a statistical quirk or a mistake. This led to some truly death-defying leaping to conclusions when this issue hit the blogosphere.

Plus ça change…

The timeline for these mini-blogstorms is always similar. An unverified accusation of malfeasance is made based on nothing, and it is instantly ‘telegraphed’ across the denial-o-sphere while being embellished along the way to apply to anything ‘hockey-stick’ shaped and any and all scientists, even those not even tangentially related. The usual suspects become hysterical with glee that finally the ‘hoax’ has been revealed and congratulations are handed out all round. After a while it is clear that no scientific edifice has collapsed and the search goes on for the ‘real’ problem which is no doubt just waiting to be found. Every so often the story pops up again because some columnist or blogger doesn’t want to, or care to, do their homework. Net effect on lay people? Confusion. Net effect on science? Zip.

Having said that, it does appear that McIntyre did not directly instigate any of the ludicrous extrapolations of his supposed findings highlighted above, though he clearly set the ball rolling. No doubt he has written to the National Review and the Telegraph and Anthony Watts to clarify their mistakes and we’re confident that the corrections will appear any day now…. Oh yes.

But can it be true that all Hockey Sticks are made in Siberia? A RealClimate exclusive investigation follows:

We start with the original MBH hockey stick as replicated by Wahl and Ammann:

Hmmm… neither of the Yamal chronologies anywhere in there. And what about the hockey stick that Oerlemans derived from glacier retreat since 1600?

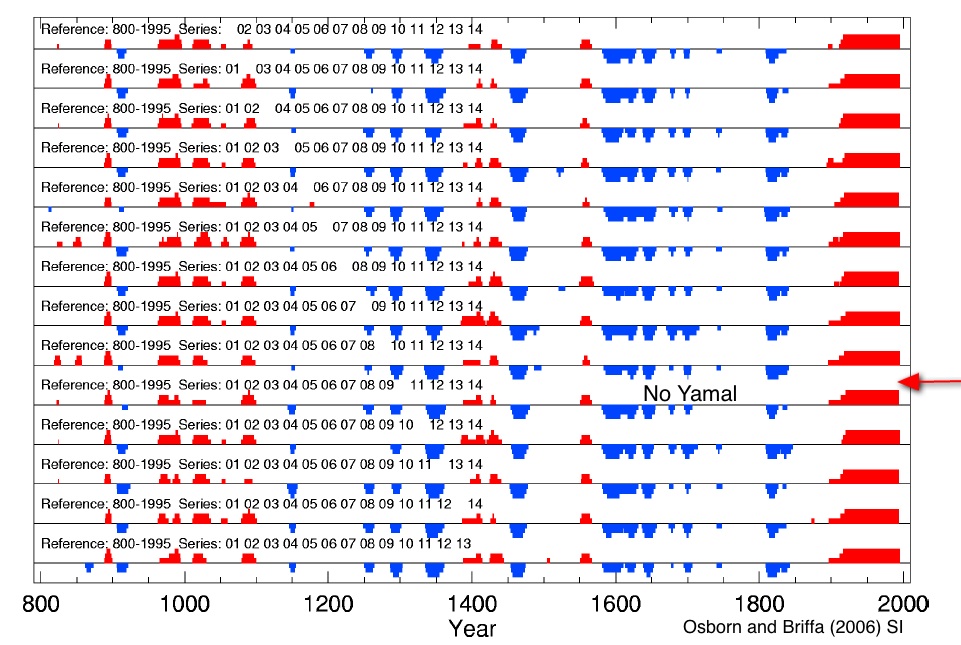

Nope, no Yamal record in there either. How about Osborn and Briffa’s results which were robust even when you removed any three of the records?

Or there. The hockey stick from borehole temperature reconstructions perhaps?

No. How about the hockey stick of CO2 concentrations from ice cores and direct measurements?

Err… not even close. What about the the impact on the Kaufman et al 2009 Arctic reconstruction when you take out Yamal?

Oh. The hockey stick you get when you don’t use tree-rings at all (blue curve)?

No. Well what about the hockey stick blade from the instrumental record itself?

And again, no. But wait, maybe there is something (Update: Original idea by Lucia)….

Nah….

One would think that some things go without saying, but apparently people still get a key issue wrong so let us be extremely clear. Science is made up of people challenging assumptions and other peoples’ results with the overall desire of getting closer to the ‘truth’. There is nothing wrong with people putting together new chronologies of tree rings or testing the robustness of previous results to updated data or new methodologies. Or even thinking about what would happen if it was all wrong. What is objectionable is the conflation of technical criticism with unsupported, unjustified and unverified accusations of scientific misconduct. Steve McIntyre keeps insisting that he should be treated like a professional. But how professional is it to continue to slander scientists with vague insinuations and spin made-up tales of perfidy out of the whole cloth instead of submitting his work for peer-review? He continues to take absolutely no responsibility for the ridiculous fantasies and exaggerations that his supporters broadcast, apparently being happy to bask in their acclaim rather than correct any of the misrepresentations he has engendered. If he wants to make a change, he has a clear choice; to continue to play Don Quixote for the peanut gallery or to produce something constructive that is actually worthy of publication.

Peer-review is nothing sinister and not part of some global conspiracy, but instead it is the process by which people are forced to match their rhetoric to their actual results. You can’t generally get away with imprecise suggestions that something might matter for the bigger picture without actually showing that it does. It does matter whether something ‘matters’, otherwise you might as well be correcting spelling mistakes for all the impact it will have.

So go on Steve, surprise us.

Update: Briffa and colleagues have now responded with an extensive (and in our view, rather convincing) rebuttal.

#698

Mark P,

First of all, I don’t think “live” vs “dead” trees is the correct distinction. Rather the crucial distinction for your question appears to be that between sub-fossils (which have generally been moved from the original site by alluvial processes) and live or dead trees at a specific site. Almost half of the Schweingruber Khadyta River tree series were from dead trees.

Having said that, I see site selection as important for choosing locations where variations in tree growth are more likely to be constrained by temperature than, say, moisture. In fact, some of the sites in ITRDB are specifically marked as “moisture sites”. But I’m not sure how one could decide if a site or an individual tree had enhanced sensitivity in advance of sampling. As far as I can see, H&S don’t explicitly say that their living trees were screened for sensitivity the same way as the sub-fossils, but it would make intuitive sense.

For me, the bottom line is as yet we don’t know enough about the purpose and methodology of Schweingruber’s Khadyta site to judge if that set of samples is a valid addition to the H&S chronology as is without further screening. That’s in addition to the weighting problem and inconsistent deletions and substitutions already noted above.

One way to resolve this would be to ask the scientists themselves directly. I’ve done that before in other situations (e.g. Mojib Latif’s so-called cooling prediction), and will do it again in this case when I have time.

Asking the right questions to the right people. What a concept!

Re 701, thanks DC

I think that’s the crux of it:- H&S explicitly say how they selected the dead (sub fossil) trees but not how they selected the living trees. The living trees are crucial to the correlation with instrumental temperature. I’m not worried about Schweingruber’s trees – so far I don’t understand how the Briffa (2000) tree set was established in an unbiased way.

The problem I have is that the H&S selection criteria seem to be:-

dead trees:- random plus inter-annual variability (random because as Jim says alluvial processes will have scrambled any location info)

live trees:- Mk 1 eyeball of skilled dendros possibly plus inter-annual variability, if used not stated (???)

unless the live trees were truly selected blindfold, and then subject to the same inter-annual variability filter, there’s a change in sampling between live and dead trees and a potential temperature bias.

Mark

PS You’re not supposed to ask questions of the right people, you’re supposed to jump up and down and say U R WRONG, BIG LIE!!!!!! :)

#703 Mark P

Also note this passage from the Hantemirov email (which was forwarded to McIntyre by an anonymous correspondent, and which I quoted in my “Backpedalling” post).

This suggests:

a) They didn’t have a lot of living trees to choose from, and

b) They selected the samples by the same criteria (although admittedly Hantemirov doesn’t say so explicitly).

Also don’t forget that the vast majority of sub-fossils came from trees along the river. In H&S 2002, the authors describe the typical sub-fossil sample this way:

So even though the exact site is not known, it would be reasonable to suppose sites of live trees “growing along the river terraces” should be roughly equivalent to the sites that gave rise to the sub-fossils in the first place.

Mark P (#699, I think),

I don’t see why. Assume that you get it right for the most recent trees in the chronology: these are selected for high inter-annual ring variability, and this variability indeed reflects sensitivity to temperature. So far so good. But once you have your recent trees, you go on to add older trees to the daisy chain. I assume you are fitting them in by determining, from the patterns of ring variability they share with younger trees, what part of their lifetime overlapped. If so, I assume you select the older trees into the chronology based not so much on the magnitude of the variability, per se, as based on the shared pattern of variability. (But the pattern happens to be one of high magnitude, both because that was what you looked for in the first trees, and because it makes the pattern stand out better).

In your example of the trees that had experienced a local flood (or perhaps grew in a flood-prone locality — not one event but several): these will show pronounced year-on-year variation around the flood year(s). But the pattern will not be a good match to that on your more recent, overlapping trees, trees that were also alive in the flood year but did not experience the flood because they grew elsewhere. So any tendency to select these trees for their apparent but spurious temperature sensitivity (an artifact of the flooding) would be countered by a tendency to deselect them because they don’t match neatly into the overlapping patterns in the chronology.

Did that make any sense? And could it actually be right? I’m just thinking out loud and know next to nothing about this subject — a treacherous combination…

You guys should spend some time reading about the use of tree rings as temperature proxies.

It’s interesting.

One thing the denialsphere keeps harping on is whether or not you can differentiate between variability due to changing temperature vs. other limiting growth factors. The reference I link about says …

People, especially McI et al, seem blind to the fact that we know anything at all about tree physiology, or that folks like Briffa use known facts about tree physiology as part of their selection criteria. For a really crazy example take a look at Lucia’s latest post (or, maybe not, you’ll gag, I’m sure).

Anyway, there’s a lot more to all this than the denialist camp is making it seem to be – it’s not just statistics thrown at datasets chosen by arbitrary selection criteria. The selection criteria is based on physiology, including one of the most basic things of all, the fact that growth is typically limited mostly by a single factor and that trees at their northern or altitudinal limits tend to be limited by temperature.

Not precip? Well, yeah, in arid ranges (this is a problem for bristlecone pines), but soil moisture remains high in many northern and high-altitude stands during the growing season – they’re deep in snow through late spring and water just isn’t a problem. LIkewise soil nutrients vary over the landscape but vary year-to-year in one spot (remember, trees don’t walk)? Typically, no. You might find individual trees that have sprouted in an inconvenient place (crack in a boulder, that might be nutrient limited) but you’ll find many that aren’t.

Also at northern and altitudinal limits stands tend to be open, thus limiting variation due to “forest dynamics” (as my reference puts it) – shading by other trees, competition for nutrients by other trees, complications due to structural complexity as you find in lower-elevation, old forests, etc.

Anyway … I think it’s safe to say that Briffa and the like know far more about their profession than people like McI and Lucia (or any of us) … and the whole naive meme that they just run around picking trees they think will show a hockey stick is crap.

“. . . the whole naive meme that they just run around picking trees they think will show a hockey stick is crap.”

Well, naive might be kind; if bad will on the part of investigators is assumed ab initio, then it is going to be easy to “debunk” the results. Which is why we see so much of this assumption in certain corners.

Good post by “delayed oscillator” on Yamal issues …

dhogaza #705

Easily available (and readable) tree-ring references I have found helpful:

* Principles of Dendrochronolgy, summary from Henri D. Grissino-Mayer’s Ultimate Tree-Ring Web Pages

http://web.utk.edu/~grissino/principles.htm

* Chapter 10 of Bradley, Paleoclimatology: Reconstructing Climates of the Quaternary (Keith Briffa). Available at Keith Briffa’s web page:

http://www.cru.uea.ac.uk/cru/people/briffa/

Also the new paper by Esper et al 2009 in Climate Change Biology, which goes a long way to resolving false detection of “divergence” in Siberian tree networks.

http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/122374111/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=1

That study examines seven “clusters” of sites in Siberia and uses a much larger set of live trees up to 2000 than previously available. Over the coming months, I would expect publication of more robust reconstructions based on enlarged data sets, use of RCS for detrending/standardization, and more careful calibration with temperature record.

Thank you for posting that link dhogaza. I was pleased to see that I understood what Briffa was talking about w/regards to replication and that McIntyre didn’t get it. I even understood the bit about “modern sample bias”, something that Steveie Mac never mentioned, and which might have affected his chronology by increasing the number of modern samples from 17 to 39 (out of 241).

BTW, the chapter he points to on RCS is quite good and provides and excellent discussion of the strengths and pitfalls of the RCS methodology.

“So any tendency to select these trees for their apparent but spurious temperature sensitivity (an artifact of the flooding) would be countered by a tendency to deselect them because they don’t match neatly into the overlapping patterns in the chronology.”

I believe that is what’s being relied upon and why you have to have more trees than just one that goes from year a to year b another going from b to c, another from c to…

And then the distribution of CO2 growth can be self-validated by other tree sensitivities over a long overlapping period AND you can deselect those that go haywire under the supposition that they’re not representative.

Finding the connection between the tree record then becomes a case of putting a jigsaw together. The overlap becomes the key to say whether you have the right piece.

It also shows why McI’s attempt is bogus: there would be no key and no self-validation. It becomes impossibly easy to make a match then, just like in a jigsaw where you’re doing the sky and all bits are the same shade of blue (or near enough). You can find out later that the piece you have put there doesn’t fit because getting more pieces out there and fitting shows that it has the wrong shape elsewhere.

McI doesn’t do jigsaws, obviously.

Re 704

CM, yes that’s what I thought they meant, and that’s what Jim alluded to in 674. The concept is that your recent trees correlate well with temperature, and you can assume that older trees which correlate well with the newer trees also correlate well with temperature. You can identify responder trees in the past using a daisy chain to the present responder trees. (I think this approach has its own problems – see below).

But that doesn’t seem to be what H&S do. Instead H&S explicitly say that they selected the trees with the largest inter-annual variability. They selected the “best” trees before any correlation took place. That is definitely not the same as selecting older trees which correlate well with newer trees, which would be selection based upon the correlation output.

There’s more on this at your post 526, Jim’s reply at 598, and at Jim’s helpful post on CA which you linked to. Jim says on that post http://www.climateaudit.org/?p=7278#comment-359804 “Those that vary the most strongly are the most sensitive to the environment”. That’s where I think the hidden assumption comes in:- this is true only if the environment varies strongly during that period. That’s making some a priori assumptions about past climate. If past climate was quite stable, H&S’s algorithm will select for trees which are responding to factors other than climate. Jim does then go on to talk about a spatial test as well. But I don’t see that in H&S. Even if there were, I don’t think it solves the problem of a priori assumptions about climate.

In a nutshell:- if climate was very stable for a period, H&S’s result won’t show it. Instead their output graph will show a variable climate during that period, which would not be correct. A simple average across all samples in the set for that period would show a result which better reflects the true (stable) climate during that period, because it will include more responder trees than H&S’s algorithm. Regardless of H&S’s (undoubted) skill as dendros, their selection algorithm seems to make a priori assumptions about climate being highly variable.

Regarding the idea of daisy-chaining trees together as you and I both thought. Sounds plausible, the problem I can see is that your correlation between generations will be imperfect, so your confidence that you have selected the climate-sensitive trees in the past will be lower than in the present. As you extend the daisy chain back your confidence will be lower and lower. You’ll start to bring more non-responding trees into the average and lower the temperature sensitivity of your tree-mometer. You’d need to correct for this in some way which my brain can’t cope with.

I still don’t get how, having spent ages gathering cores and turning them into wiggly lines, it’s a good idea to reject a large part of the data sample simply because the lines aren’t wiggly enough. Surely the wiggles are the wiggles, and unless there is some external metadata which gives you good cause for not using them, all the wiggles should be included??!

Mark

dhogaza: your link states “MXD in northern conifers is very strongly related to summer temperatures”.

Grudd (Clim. Dyn. 2008) updated the Tornetrask MXD data to 2004. Grudd’s conclusions were:

“Tornetrask MXD does not show this ‘‘divergence problem’’and hence produces robust estimates of summer temperature variation on annual to multi-century timescales.

The late-twentieth century is not exceptionally warm in the new Tornetrask record: On decadal-to-century timescales, periods around AD 750, 1000, 1400, and 1750 were all equally warm, or warmer. The warmest summers in this new reconstruction occur in a 200-year period centred on AD 1000. A ‘‘Medieval Warm Period’’ is supported by other paleoclimate evidence from northern Fennoscandia, although the new tree-ring evidence from Tornetrask suggests that this period was much warmer than previously recognised.”

The late-twentieth century temperatures in northern Fennoscandia seem to be perfectly normal, no hockey stick there.

“I still don’t get how, having spent ages gathering cores and turning them into wiggly lines, it’s a good idea to reject a large part of the data sample simply because the lines aren’t wiggly enough. Surely the wiggles are the wiggles, and unless there is some external metadata which gives you good cause for not using them, all the wiggles should be included??!

Mark”

But you don’t get the wiggliest jigsaw piece and slam it in the jigsaw, do you.

It has to fit with all the other pieces else you won’t get the real picture.

Well, let’s see, if temperature and precipitation are stable, what will those other factors be? Again, it’s not as though we know nothing of tree physiology, right, and they’re not looking at raw ring width but at a kind of growth known to correlate well with summer temps.

Thanks, Jari, now, if RCS analysis on MXD data from tree ring chronologies work well in Northern Fennoscandinavia, is there any reason for us to believe that these techniques don’t work well on the Yamal pennisula in Siberia or the other areas where “hockey stick” reconstructions have been made?

Or are you suggesting that since one regional reconstruction doesn’t show a pronounced “hockey stick”, then all the other regional reconstructions using the same techniques must be wrong?

Re 695, 713

I’ve got it – we’re arguing violently about two completely different things! I think there is a strong distinction here between dendroCHRONOlogy and dendroCLIMATology and how the sampling should work in each case.

dendroCHRONology is about looking for extreme trees. The more extreme a tree’s growth pattern, the easier and better you can reconstruct a chronology. DendroCLIMATology is (or should be) about looking at average trees, because in a region with localised non-climate events, only widespread averages can give you a proper climate signal.

In dendroCHRONology you are NOT interested in what caused a change in ring width. In particular you are not interested in how spatially widespread the change in ring width is. You are only interested in building the cross dating jigsaw, and you are looking for a few long lived trees with “distinctive patterns” of growth. In this case selecting the small number of trees with the widest inter-annual variation makes perfect sense:- it gives you the most distinctive pattern and the most accurate cross dating.

In dendroCLIMATology you are ONLY interested in what caused the change in ring width. You want to detect changes caused by climate and reject changes caused by localised events. The way to do this is to measure how spatially widespread the change in ring width is. For a random sample set like H&S you need to measure how widespread it is across the sample set. The more widespread the change, the more likely the effect was caused by climate as opposed to localised non-climate things. The more samples you use, the better able you are to distinguish climate effects from localised effects.

It looks to me like H&S have performed a very valid dendroCHRONological assessment:- they have taken 2000+ samples, and selected the 200+ longest lived with the highest inter-annual variation (“most distinctive growth pattern”). This will give them a highly accurate dendroCHRONOlogical reconstruction.

But for a dendroCLIMATological reconstruction we need to look for ring width changes that are widespread among the sample set. That’s much harder to do from the small set of post-selection samples than it is from the large set of pre-selection samples. Particularly since the selection algorithm was targeted at dendroCHRONOlogy and might not always select the “best” climate responders.

At any given time in history (say AD 1500), H&S rejected of the order of 90% of their data set to build their chronology. But when it comes to reconstructing climate, the reconstruction suffers very badly from sampling error:- they (or Briffa) are trying to estimate wide-area climate signals from just the 10% of selected trees, rather than from the 100% of the whole sample set. And given that that 10% of trees have been selected by a non-random algorithm (as, possibly, have the living trees) there is the potential for systematic bias. In low signal to noise studies like these, bias is deadly.

That explains why we are at cross purposes. Your position is that you can build a very accurate dendroCHRONOlogical reconstruction from a handful of trees, and I fully agree with that.

But as far as dendroCLIMATology goes, my two original questions still stand:-

1 – “how can you infer anything about climate from a handful of trees?”. Specifically, how can you infer anything with confidence about the climate in the Russian forest at AD 1500 from examining a few tens of trees

2 – “don’t H&S’s selection criteria introduce a temperature bias into the deep past climate reconstruction?”. This comes in two parts:- how they selected the living trees vs selecting the dead trees; and how they selected the ~10% and rejected the ~90% of dead trees in the deep past reconstruction.

And the answers I’ve been getting are (1) yes you can and (2) it doesn’t matter. But those answers I think are referring to dendroCHRONology in which case I agree entirely.

Hope this makes some sense.

A much more flippant answer:-

At a given time in the past, say the 15th century, you have 100 randomly selected tree samples.

– 90 of them show a very similar variation in ring width over that period, say a slow increase

– 10 of them show much larger variations over the period, the variations significantly different from tree to tree.

Which set “best represents climate”….

(a) the 90?

(b) the 10?

(c) the 100?

A: it has to be (c) doesn’t it?? You have no information with which to say some of these randomly selected trees are better than others. You can’t select the 10 more variable over the 90 less variable without making the a priori assumption that climate was highly variable during the 15th century. You can’t select the 90 rather than the 10 for the same reason. You have to use the 100 and infer climate from what the majority of trees were doing with appropriate confidence statistics.

Sorry for the flippancy, it’s getting to beer time.

Not really, sorry to disappoint. You could start by reading some of the references that have been posted. I learned a lot by doing so. I humbly suggest that learning how things are done is more sensible than, say, building your own strawman version to shoot down.

#713, #716

As was already pointed out the “more wiggly” lines are easier to crossdate precisely, besides containing more climatic signal. And presumably the selection is for interannual variation relative to other trees of the same era.

Also note that H&S say:

So in this case, the main limiting criterion was the length of the tree series. As I noted in some detail at my blog, though, a forthcoming Yamal study from Hantemirov uses RCS and includes shorter series, and many more live tree series. That reconstruction is still similar to Briffa et al 2008.

I agree that the selection of live trees is not 100% clear, but we do know they were selected for age as well. Crossdating is not an issue, so there may or may not have been selection for sensitivity. To what extent the age was determined pre- or post-sampling (i.e. to what extent they could determine age and not bother sampling younger trees) is unknown. But this is probably not relevant considering that Hantemirov has now boosted its live tree set to 200 series.

I also note that most of your questions could be answered by reading the paper. For those interested, here it is:

A continuous multimillennial ring-width chronology in Yamal, northwestern

Siberia, Rashit M. Hantemirov* and Stepan G. Shiyatov, The Holocene 12,6 (2002) pp. 717–726

http://www.nosams.whoi.edu/PDFs/papers/Holocene_v12a.pdf

To me the crucial point is this: A lot of the “analyses” out there imply or even state that any regional reconstruction showing a hockey stick is simply the result of “cherrypicking” the subset of noisy data that happens to correlate with temperature in the modern era. That’s simply not so.

#712

Something that has been lost in the shuffle is that Briffa et al 2008 also covers Fennoscandia, and Avam-Taymir, not just Yamal. It is thus a super-regional reconstruction of temperatures in Norhwest Eurasia.

Full text PDF available at:

http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/363/1501/2269.full.pdf

Of the three regions, Fennoscandia shows the least variation. The smoothed reconstructions (Fig. 3) shows 20th century and MWP have roughly equivalent peaks, although a 200-year filter might well show more sustained warming for the MWP. Overall for the three regions, Briffa et al do show 20th century above MWP.

A final thought: For me, the point of temperature reconstructions is not so much the exact relative warmth of MWP and current era globally, although previous Eurocentric notions of a much stronger MWP are almost certainly erroneous. But the real take away is the unprecedented rate of current global warming relative to the last two millenia.

Deep and Dhogaza, thanks for the reading list. I promise at least to get through it before extemporizing on tree rings again!

Mark P, just a couple of last thoughts that shouldn’t depend much on physiology:

I’m not convinced your account of their method is quite adequate, but even if it were, I don’t think this would follow. High *overall* interannual variability in a series is compatible with the series showing *relatively* less variability over a period of relatively stable weather. (And *climate*, by definition, is something you get by *averaging out* interannual variation.)

To all of you for being civil and educational, and to Mark P for raising interesting questions, thanks; it’s been a glimpse of the RC comments section as it could be.

I notice a lot of ad hominem here, and a lot of “kill the messenger” as well.

I have to say that I see very little of that at Climate Audit, especially from Steve McIntyre, who couches his observations in extremely careful language.

I’m not persuaded by noise, and I read a lot of noise here.

—————————————————————–

RE #488: “Don’t be obtuse! Gavin is alluding to the fact that a sensitivity >2 has >2.5 million years of evidence in favor of it, while Lindzen’s “analysis” has… well, none. See the difference?”

You are wrong Ray. It is very difficult to get published with no evidence in favor of your position. I suggest you read Lindzen’s paper: http://www.drroyspencer.com/Lindzen-and-Choi-GRL-2009.pdf

[I am not claiming Lindzen’s sensitivity estimate is the correct one, just that Gavin’s ground for dismissal are not reasonable.]

[Response: Sorry, but I disagree. If someone claims to have made a perpetual motion machine I don’t need to read up to page 10 to know that they haven’t. The ice ages could not have happened if sensitivity was as low as 0.5 deg C/2*co2. Therefore there is something wrong with an analysis that says it is. -gavin]

——————————————————————–

This might be THE most important paper this decade and you won’t even read it?? And please tell us why the ice age could not happen with a sensitivity at 0.5 C/2*co2. If you follow your line of thougth this result would be in line with the abolishment of the medieval warm period and the little ice age in the various hockeystick grafs.

[Response: Of course I read it. The issue with the ice age is that we have reasonable estimates of the forcings and reasonable estimates of the temperature changes and they imply that sensitivity is around 3 deg C. If sensitivity is only 0.5 deg C, then we would have had to have made an error of a factor of six in temperatures – i.e. it was only 1 deg C colder instead of 6 deg C colder, or that we have underestimated the forcings by a factor of six – i.e. a forcing of -48 W/m2 instead of -8 W/m2. Doesn’t sound very likely. The same goes for the Little Ice Age – you’d have to find 6 times the forcing that we think was happening. Thus it is highly likely that Lindzen’s paper will not turn out to be a robust analysis – time will tell! – gavin]

[edit]

Re 719

Thanks for the link, it didn’t answer any of my questions, but it is very interesting. Having read it, I can boil my criticism and all previous questions down three words:- no error analysis.

H&S Figure 8 has no error bars. It’s a statistical study; in a low signal to noise regime. It must have error bars. where are they? Even more, H&S contains no section called “error analysis”. It contains no instance of the word “error”, or of the word “confidence”.

With respect to the climate reconstruction, the error analysis section should cover….

– errors due to the selection methodology for living and dead trees

– errors due to the imperfect chronology reconstruction

– errors due to the imperfect instrumental record

– errors in confidence due to the imperfect correlation with the instrumental record

– errors due to the low number of samples in the climatic reconstruction set

– errors due to H&S’s choice of that site vs other sites in the area

– loads of other stuff that would occur to a smart statistician or dendro.

But there’s not a mention of the word “error” in the whole paper.

It’s impossible to draw any conclusions about the science in Figure 8 without error analysis.

To be absolutely clear “error” does not mean “we got it wrong”. It means “Mother Nature is a b***h, but we’ve taken account of that, and our result is still valid”.

:)

I had no inkling that H&S did not show a hockey stick in their reconstruction (Fig 7)! But Briffa (2000) uses the same data set, and a different methodology, and derives a humungous hockey stick in its RCS reconstruction.

The methodology is simply a way of extracting the signal from the data set. Does the data set contain a hockey stick shaped growth signal or not?

If yes, then H&S’s methodology is not sensitive enough to detect it. H&S’s error bars on Fig 7 need to be large enough to accommodate the idea that there might be a hockey stick signal, but the methodology can’t find it.

If no, then Briffa (2000)’s hockey stick is an artefact of the methodology. Briffa (2000)’s error bars need to reflect the fact that the hockey stick might be an artefact, not a real signal.

In summary, the error bars on H&S and Briffa (2000) should overlap. If they don’t, at least one of the analyses is wrong.

[Response: H&S remove any possibility of capturing century scale variability because of their standardisation method. Briffa (2000) does not. Therefore the century scale trends cannot be expected to overlap – it’s like comparing high frequency variability in the temperature and demanding that the error bars include the global warming signal. Not appropriate. – gavin]

Mark (693):

I think some wires got crossed somewhere from the difficulty of explanation. I’ll back up and try again, but since you have a real interest here, and there are numerous issues, you will need to wade into the literature. Fortunately all the online stuff like (especially) ALL the old TRB issues, the stuff at e.g. LTRR, Lamont-Doherty, Birmensdorff and Henri Grissino-Mayer’s web-site, Tom Melvin’s dissertation linked to here, etc., can get you a long way. If you can get hold of a copy of Hal Fritts’ bible, Tree Rings and Climate, DO IT.

Two things are absolutely required:

(1) The ability to cross-date the samples and

(2) Responsiveness of ring variables to temp

1. Living trees are selected based primarily on taxon and site characteristics, as informed by previous observations/samples informing of the general response of such to some limiting climate factor. The higher you can make the s:n ratio, by constraining the site factors (and hence the influence of other environ. factors), the better. But once defined, you then sample +/- randomly within that environmental space, with the constraint that you are also trying to get the oldest specimens, to carry the chron. back as far as possible before having to resort to dead wood. Unless you have legitimate reason (e.g. strong ring complacency combined with frequent missing rings, making cross-dating very tenuous to impossible), you do NOT bias the sample by the observed ring patterns of given trees, once collected; you do not artificially lower the variance by choosing only the ones that correlate most strongly with the instr. recod. When I said that having working thermometers is criterion #1, I meant within these constraints. Thus, as I also said, sampling is based on site and taxon stratification, as informed by previous understanding of response to climate, and NOT by the characteristics of the rings of particular trees post facto.

2. All of your sampling of any dead wood is then constrained to be within the same strata as the live trees are. This is straightforward in most dendro studies, but is complicated in the Yamal work by the fact that for some fraction of the trees, you do not know where they grew. But you do know they most likely grew in the riparian zone, and can thus sample the living trees in that same zone.

3. HS’ use of inter-annual variability as a selection criterion for the buried trees is necessary for cross-dating the samples. It also inceases the odds that the trees are responding to some environmental influence.

4. Evidence for the possibility that something other than temp was operational in the past is provided by examining the spatio-temporal patterns, and magnitudes, of ring variations. If these are similar to current, you have a very hard time arguing that some other factor was primary, and absolutely no way to prove it. Hydrologic effects on tree growth typically operate at very different (generally smaller) spatial scales than temperature effects do, even in relatively flat and wet terrain like the tundra, where you might not expect this. How does the snow deposit?, where does it melt out first?, how dry does the rooting zone of hummocks get in mid summer?, where is the flood plain and what’s the flooding pattern?, etc. etc. These points are critical, and are but examples of why I said before–and will say again, and then again, and again–that the on-the-ground understanding of someone like Shiyatov (whom I note in correction, has been studying Siberian larch since at least 1965), of the response of a given taxon to the fine-scale spatio-temporal climatic patterns of the region, is utterly invaluable. You cannot imagine how much working knowledge about tree growth and tree rings is held by people like H&S, Briffa, and Schweingruber. The latter two, as far as I can tell, know as much about tree rings, and their analysis as env. proxies, as any two people on the planet probably ever have. They are the experts; I’m a hacker (but I do try hard).

I see there has been a bunch more comments, but I have not had the time to read them. I will try to do so and give my view as time allows.

“Which set “best represents climate”….

(a) the 90?

(b) the 10?

(c) the 100?

A: it has to be (c) doesn’t it??”

Not really, if

(a) 90 good numbers

(b) 10 bad numbers

(c) 100 made up numbers

Worse, H&S want to use the 10.

Jim, thanks for your detailed post, very informative …

I’m finding it very frustrating that the McI crowd seems to think that researchers shouldn’t apply their knowledge of tree physiology (response to changes in various environmental factors), site attributes, etc when doing such studies. They seem to think all trees are created equal, and that either every tree responds mostly to temperature changes or none do, regardless of site considerations.

It boggles the mind dhog. Dendroclimatology critiques of world experts, via the web, sans knowledge of tree behavior or intentions of the data collectors.

#724

I linked to the H&S paper so you could understand methodology and see how and why samples were selected, including rates of retention based on ability to crossdate.

Briffa took the same data and applied RCS, which permits analysis of multi-decadal and centennial trends of interest (as Gavin said).

#725

Jim, thanks for weighing in again – much appreciated. The one question still outstanding for me is whether H&S applied the same criteria of sensitivity to living tree samples as buried ones, even though it’s not strictly necessary for cross-dating. So far, the answer seems to be that one would have to ask Hantemirov directly, which I still intend to do when I have the time to formulate my questions (now that his DSc session is out of the way)!

It would be bad enough if it were just a question of sloppy analysis accompanied by what appears to be a complete lack of domain knowledge. That the “analysis” is conflated with implicit and explicit accusations of scientific misconduct makes it even worse.

#721

I had to reread that a couple of times to make sure that wasn’t a joke. Here’s what you really find at ClimateAudit:

* Constant referrals to cherrypicking. 913 ClimateAudit posts refer to this somewhere in the post itself or in comments. I’m sure they’ll reach the 1000 mark some time next year. WUWT is only at 765; clearly Watts and co need to step their game. (Hmmm – I’m getting a good idea for a future DC post).

* Regular explicit and implicit accusations of plagiarism and other scientific misconduct.

* Comparison of Yamal (in at least three different posts) to “crack cocaine” for multi-proxy studies.

Those are the facts – please don’t shoot this messenger.

Gavin, re your 724,

>> “H&S remove any possibility of capturing century scale variability because of their standardisation method. Briffa (2000) does not. Therefore the century scale trends cannot be expected to overlap – it’s like comparing high frequency variability in the temperature and demanding that the error bars include the global warming signal. Not appropriate.”

thanks for pointing this out, you are absolutely correct, the H&S text says “However, fluctuations of summer temperatures on annual , decadal and part-century timescales are discernible.”. The question is, of course, what does “part century” mean?

Overall it’s a very helpful example of what I mean in 723 re “Errors in the imperfect chronology reconstruction”. We can’t understand what H&S can and can’t detect without a detailed error analysis, particularly the impact of their standardisation method on Figures 8 through 11.

The text makes a couple of statements which and seem to contradict your 724 and certainly confuse me. With reference to Fig 11a H&S state:

“… other, longer, cool periods included 500 to 280 BC (perhaps even to 190 BC), and AD 1600–1750.” and “The long warm period that lasted from about 10 BC to AD 160 is also a remarkable feature of the reconstruction”. These time periods are, respectively, 220 years (perhaps 310 years); 150 years and 170 years.

– How can H&S make these statements with confidence if the methodology is only sensitive to part-century timescales?

– If they can detect with confidence two-century long changes, how come they didn’t detect the hockey stick in any shape or form?

This is exactly what I mean by error analysis:- H&S themselves seem to be confused about what their methodology can and can’t detect; if they can detect 220 year long periods, why didn’t they detect the hockey stick?

[Response: It’s a function of what is called the ‘segment length curse’ (look it up) – you generally have longer-lived trees further back in the chronology. However, since I am not H or S, nor am I any kind of dendroclimatologist, nor do I have any special insight into how or why they wrote this paper the way they did, I’m afraid I can’t answer any questions about that. Why don’t you email them to ask? – gavin]

In his helpful post 725 above, Jim Bouldin refers to (2) “the responsiveness of ring variables to temperature”, but then (so far as I could see anyhow) doesn’t discuss it.

Being a gardener, planting and nurturing quite a few trees over the past few years, I can’t help but notice that trees do best when temperature and moisture conditions are optimal (and when other factors such as soil type, availability of nutrients, degree of compaction, surrounding weed control etc are supportive).

I have two questions (which no doubt have been answered many times at this site).

1. When temperatures are too low, trees don’t thrive. When temperatures are too high, trees don’t thrive. This means that the tree has an inverse quadratic response to temperature. Narrow rings can represent either temperatures that are too low or too high. Thick rings represent temperatures that are “just right”. In my readings on dendroclimatology, it appears that the assumption is made that thicker tree rings mean higher temperatures. How does this work?

2. When moisture is too low (or too high), trees don’t thrive even if temperatures are optimal. How does dendroclimatology take moisture variations from season to season into account.

I did google “inverse quadratic response of tree rings to temperature” and noted numerous references including from C Loehle and Fritts 1976 that seem to support my observations, but none from names that I recognise as being associated with this site.

Thank you.

Remember, they’re selecting climate-stressed trees to start with. Trees near their northern latitudinal and altitudinal treelines, where the growing season is short. It’s knowledge of tree physiology that tells them that near the treeline, the temperature during the very short summer growing season is the dominant factor controlling growth. They’re also looking for a tissue type that is known (through studies into tree physiology, one presumes) to be sensitive to late growing season temps.

These claims aren’t made for *all* trees in *all* circumstances. Just *some* trees in *specific* circumstances.

Jim talks about it above. Please re-read the #4 section of his post.

I don’t get how McIntyre can say such things about experience scientists. His armchair dendro work is not useful in any way. Perhaps he should get out of his basement, and read some actual papers and he might understand how things actually operate in that field of science.

Here’s a hint. Esper, another accomplished dendroclimatologist, has explained why sample levels might be low.

“However as we mentioned earlier on the subject of biological growth populations, this does not mean that one could not improve a chronology by reducing the number of series used if the purpose of removing samples is to enhance a desired signal. The ability to pick and choose which samples to use is an advantage unique to dendroclimatology.”

Journeyman,

Steve doesn’t need to read actual papers, he needs to take a few actual undergraduate classes in plant biology and some lower level grad classes in dendrochronology and dendroclimatology.

BTW, he has another post up about how he likes Polar Urals better than Yamal. Both seem fairly consistent with each other until about 1000 AD. at which point Polar Urals shows a substantially higher value than Yamal. Steve pushes using Polar Urals (updated, I think, but it is hard to tell just from reading his turgid prose) since Polar Urals is more “highly replicated”. While this is true during the instrumental period, Yamal has consistently the same or more cores going back in time. During the period of interest, Polar Urals has about 1/2 the number of cores that Yamal has.

Since I posted this at CA, I have my asbestos suit on. However I will maintain, as Steve often does, that more data is better than less data. My guess is that Polar Urals (updated) suffers from modern sample bias which is why Rob Wilson didn’t trust the RCS results for Polar Urals (updated).

From 699:

“What H&S have done seems to involve a hidden assumption:- that the inter-annual temperature variation was high at all times in the past. I can’t see any justification for this assumption, without a-priori knowledge of inter-annual temperature variations in the past.

During periods when inter-annual temperature variation is low, the trees which best represent temperature will be those with low inter-annual variability. But H&S’s algorithm in such periods will select the wrong trees:- ones which have suffered from small-scale events which were spatially inhomogeneous.

So for example if there was a long period of stable temperature, but during that time there was a localised event affecting part of the region (eg a flood), H&S’s algorithm will select the trees in the flooded region, because they show a larger inter-annual variation. But that variation was a result of the flood, not temperature changes. This won’t affect the chronology, but it will affect the temperature reconstruction.”

Mark, you are stuck on this point and getting it wrong, and it is because you are making too much of HS’ statement about employing interannual variability in choosing their buried samples. They do not assume that inter-annual variation was high at all times in the past, and I have no idea where you got that idea. Let’s go step by step.

Many of their samples could not be cross-dated–about 65% of those under 100 years, some unstated % between 100 and 150 years, and 20% of those over 150 years. If you cannot cross-date your samples, pack up your bags, see what you can get for your borers, and start scanning the want ads, because you CANNOT construct a chronology. Therefore, their emphasis on longer series (which also helps cut sample prep time), and, in general, those series whose high freq variability is highest…so that you can cross-date them.

To cross date, you do not need consistently high sensitivity (high freq variability) throughout your various series. You just need enough so that you can readily, visually identify diagnostic “pointer” years, or groups of years, in what are known as skeleton plots–plots of unique and identifiable years of high or low growth, or groups of consecutive years with a certain pattern that you can look for across your full set of ring series. In between these pointer years you may well have little or no variability for some time, depending on the climate patterns, and if that even-ness also recurs across multiple samples, it also becomes a pointer and you know you’re onto something–some type of common environmental signal across your trees in a defined time and space domain. There are also computer programs that do this same thing, but they require that you’ve got the ring measurements first, whereas skeleton plotting does not (thus potentially saving a lot of potentially needless, and tedious, ring measurements).

The very nice thing about this, is that, as I’ve already stated, the fact that you can cross-date trees across a big space (many miles in this case) MEANS, NECESSARILY that you have a common environmental driver forcing those patterns. There are far too many rings involved for this to occur by chance. Why are you not getting this?

So the cross-dating kills two birds with one stone–it lines up the cambial years according to their calendar year, and provides spatio-temporal information on some external driver of ring widths (or density or what have you).

As a sort of larger, general point, I think in some respects you are making one of the same mistakes that McIntyre makes, which is to assume that all the issues involved here are strictly statistical and strictly explicit, with no allowance for the fact that there might be a whole body of subtle, discipline-specific knowledge that comes into play, but which is not always explicitly stated by people writing for their peers in a space limited publication. There’s more to it than meets the eye, as is almost always the case with anything.

m, I’ve finally got it! Thanks for your patience. I don’t think we’ll ever agree about whether or not “largest inter-annual variability” is a good criterion or not. But I fully understand and agree with your point “The fact that you can cross-date trees across a big space (many miles in this case)MEANS, NECESSARILY that you have a common environmental driver forcing those patterns”

So the most important selection criterion for trees in the climate reconstruction seems to be good spatial diversity (trees from across a big space). Without a good spatial diversity, the climate reconstruction fails, because you might be looking at localised events. Got it. Thanks.

Can you help me find that criterion mentioned in H&S (20002)? I’ve been through it again and again, particularly the chronology and climatic reconstruction sections, and I can’t find any mention of a spatial selection criterion. The start of the corridor standardisation section explicitly states “224 individual series of subfossil larches were selected. These were the longest and most sensitive series, where sensitivity is measured by the magnitude of inter-annual variability”

As far as I can see, only two selection criteria are mentioned:- age and variability. Is there a third, much more important spatial selection criterion which is not mentioned in the paper? What is the precise nature of that criterion (kilometres, metres?)

Given H&S’s earlier statement that” Living trees, growing along the river terraces, are undermined and often fall into the running water (Figure 2). This occurs mainly in spring and early summer, when water level and stream velocities are high” and your helpful explanation in 674 that “many of [the trees] may have been moved from their growing location by alluvial processes” what kind of spatial criterion can H&S apply? It would have to be very carefully designed to avoid spurious capture of trees which were in close proximity during life but have been spatially separated in death.

Of course, the validity and impact of such a key selection criterion would also have to be very carefully assessed during H&S (2002)’s error analysis……..

Re 737 Mark P

“So the most important selection criterion for trees in the climate reconstruction seems to be good spatial diversity”

No, that’s not what Jim said at all.

The most important thing in constructing the chronology is that you can cross-date the overlapping cores.

Say you have a living tree that goes back to 1800. The first 20 rings in that tree are (W is wide, N is narrow): WNWWNWNWNWWNWNWWWWWW. If you have a dead core which also contains the sequence WNWWNWNWNWWNWNWWWWWW, you can be pretty confident that the dead core overlaps the period 1800-1820.

Now, I have only used two categories of ring-width, wide and narrow, whereas in reality the widths are all over the place – what you are looking for is the relative widths of the rings within each sequence.

A tree which expresses high inter-annual variability will make it much easier to detect these kinds of patterns, especially as we are talking about measurements of a small number of millimetres.

Take these two sequences of numbers, and assign them to W/N:

11-12-11-11-12

11-18-9-12-19

You could say that both are N-W-N-N-W. But it is equally valid to say that the first one is N-N-N-N-N, given that all of its values are within the band you have assigned to N in the second sample. The first sample may or may not be responding the same way as the living tree you are trying to match it to, but there is no way to be sure, so it will be rejected.

The second sample can be matched against your reference sample with much higher confidence. If it matches, then it must have been responding to temperature for at least the period where it matches the living tree, and is almost certainly a good thermometer.

On the other hand, if you can’t cross-date the second sample to another known core, then you cannot use it, even though it has large inter-annual variance. The variance alone is not the criterion for whether or not it ends up in the chronology.

(at least, that is my layman’s take on it – I’m an animal biologist, so I don’t really understand trees :-)

Mark, it’s inherent in the very objective of their paper–a multimillenial chronology of the entire southern Yamal region, as defined in their Figure 1, showing their sampling sites across the four main rivers over a ~ 10,000 sq. km area. That’s how they defined it, therefore we can be pretty sure they didn’t spend time traveling up and downstream, cutting out samples from sandbanks and peat mires while being sucked dry by mosquitoes, then transporting, surfacing, examining and measuring them, so that they could then use only those from some smaller area. Right?

CTG, Re 738, I absolutely agree with what you say as regards crossdating. I fully understand that and your excellent example shows how high inter-annual variability gives confidence in cross dating.

My problem comes with the climate reconstruction part. I think the selection criteria which work well for cross dating work very poorly for climate reconstruction. You’re a biologist:- I hope you can agree that dating is about extrema and “unusual” events; widespread climate response is about averages. I hope you would also agree that avoiding selection bias is vital.

I like the idea of a selection methodology for CLIMATE which matches old to new samples which is what you describe. That’s not what H&S do, but we’ll come on to that.

>> “The second sample can be matched against your reference sample with much higher confidence. If it matches, then it must have been responding to temperature for at least the period where it matches the living tree,

Your definition of “matches […] with much higher confidence” can only mean “correlates well with”. I can’t see any other relevant way to define “matches”. Extending your excellent example to the CLIMATE reconstruction:-

In the overlap period 1800 – 1820 the living tree ring widths go 2-4-6-8-10-12-14-16-18-20-2-4-6-8-10-12-14-16-18-20 in millimetres.

We then have two dead trees, both died in 1820. We want to select the dead tree that “best matches” the living tree “and is almost certainly a good thermometer”. During the overlap period the two trees go:

Tree 1: 1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30 mm

Tree 2: 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10 mm

Tree 1 correlates very badly with the living tree. Tree 2 correlates perfectly with the living tree. Tree 2 “matches” a living thermometer much better and therefore probably is a good thermometer.

But Tree 1 has higher inter-annual variability, so H&S’s selection algorithm will select Tree 1 and reject Tree 2. Tree 1 is not a good thermometer, but it’s been selected into the CLIMATE reconstruction.

If H&S want to select older samples that match well with newer samples, they need to choose Tree 2. The only way to this is to do the correlation match and test the output against some threshold – “are these trees a good match?”. To be absolutely clear, that is not what H&S do. my position is that for the CLIMATE reconstruction their “highest inter-annual variability” criterion is inappropriate and causes a bias.

Mark

738, CTG. Several people (including me) have independently come up with this idea of what H&S are doing. I think it’s a great idea, but it has its problems. I don’t think that it is what H&S are doing (see the other post I’ve just sent) but even if it is I think that there is a selection bias problem.

As you’ve already spotted, the key words are “[the older tree is] ALMOST certainly a good thermometer” (my emphasis). You’re right, if the newer tree is a good thermometer, and the older tree “matches” it, then there is a high probability that the older tree is a good thermometer. But that “high probability” is necessarily less than unity, since there is only a finite number of years over which to compare the trees, and that overlap is less than the trees’ entire lives.

The problem is then you daisy chain back through time, comparing the older tree with an even older tree and trying to judge whether the even older tree is a thermometer.

Say the “high probability” that two trees match is 95% (or pick a number).

You are 100% confident that your living tree is a thermometer.

The 1800 AD tree matches well with the living tree, you are 95% confident that the 1800 AD is doing the same thing as the living tree, so you are 95% confident that the 1800 AD tree is a thermometer.

The 1600 AD tree matches well with the 1800 AD tree, you are 95% confident that the 1600 AD tree is doing the same thing as the 1800 AD tree. But you are only 95% confident that the 1800 AD tree is a thermometer, so you are only 95% x 95% = 90% confident that the 1600 AD tree is a thermometer.

Repeat for 1400 AD, 1200 AD etc etc back to 2000 BC.

Your confidence that long dead trees are thermometers is (confidence in the match between two overlapping trees) ^ n where n is the number of trees in temporal daisy chain.

H&S go back 4000 years, that’s of the order of 20 tree lifetimes. Even if their confidence between generations was 95%, 0.95 ^ 20 = 35%, using this example they would be only ~35% confident that the 2000 BC trees are thermometers.

That means when they come to reconstruct temperature there is a selection bias. For example if for any period in time they have 10 core samples, In AD 1990 their sample set consists of 10 good thermometers. Their 2000 BC sample set consists of perhaps 4 good thermometers and 6 broken thermometers. When they generate the temperature for AD 1990 they average across these 10 good thermometers. When they generate the temperature for 2000 BC they average across 10 thermometers of which 6 are “broken”. Say the good thermometers all read 10 Celsius and the broken thermometers all read 0 Celsius. For AD 1990 they would get an average temp of 10 C. For 2000 BC they would get an average of 4 C. Even though the “actual” temperature was 10 C in both cases. Their 2000 BC thermometer reads very low. There is a selection bias.

Of course the actual bias depends on the confidence between generations; the number of trees in the temporal “daisy chain”; and the exact nature of the “broken” thermometers. But I think unless the confidence between generations is very, very high the bias exists.

You could correct for this, but it would take some pretty fancy maths and argument. H&S describe none of this kind of thing. And of course it would need to be tested in the error analysis.

Does this make any sense to you? I have been going over and over this in my mind and can’t see a way around it.

Thanks

Re 736 and inter-annual variability, Jim I apologise, I’ve thought about it some more and I think you are absolutely correct on this. PROVIDED there is a strong spatial selection criterion ensuring that samples are very well spaced across the region, then choosing samples based on highest inter-annual variation is probably not an unreasonable thing to do.

Please ignore my comments addressing 738, I think that whole strand is a red herring.

I see why you got so frustrated with me. I’ve posted another bunch of stuff here as well re the spatial selection criterion, that all still stands, this comment is purely addressing the temporal selection criterion. Hope you can help me with it.

Mark

Oh, gosh, someone working in the field as a professional might be right, and you might be wrong.

Who could’ve imagined this outcome?

Mark,

No problem. I don’t know how it appeared, but I wasn’t that frustrated, a little yes, but I know you are trying hard to wrap your mind around it, and I appreciate it. I’ve been there myself, including at this site when I first arrived. If HS had in fact been selecting trees strictly on the basis of high freq variability, then your questions are perfectly valid. And certainly, questions about what past ring variables actually indicate about past climates are not only important, they are central to the science.

Regarding the spatial aspect, the key thing there is the different scales at which the likely important climatic variables operate, relative to the physiology and anatomy of a tree. In many cases, temperature and rooting zone moisture (not precip per se), including sub-annual values thereof, are the dominant drivers. So when HS observe a ring pattern on a larch growing on a hummock near the river bank, and see that same pattern on others, even of other taxa, on similar hummocks, but 1, 10, 50, 100 km away, and at the same time observe a very different ring pattern on larches growing only a few meters away, but in a depression that never dries out throughout the season, they are justified in making strong inference about the drivers of these differences, both in the present and in the past. That’s the key idea.

Re 743. Fair enough, I’ve got no problem with that. I know nothing about dendro at all. My problem all along was to read and re-read H&S (as recommended by you) where they make no mention of a spatial criterion. In the absence of a spatial criterion, a variability criterion makes no sense at all. Sorry to waste your time and impute your reputations.

[edit]

Cheers now :)

Mark

Not a problem dhog. We’re all here to learn–Mark more than most I’ve seen. And it’s tough to wade into the literature of an unfamiliar topic which has lots of subtleties/complexities.

I know you have retracted your position, but I just want to point out something from your comment 740. You give the example of a living tree with ring widths: 2-4-6-8-10-12-14-16-18-20-2-4-6-8-10-12-14-16-18-20 and two dead trees that are putative matches:

Tree 1: 1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30-1-30 mm

Tree 2: 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10 mm

You claim that the H&S selection method would pick tree 1 and not tree 2. You are completely missing the point about cross-dating.

Tree 1 does not share that unique signature for the time period 1800-1820, therefore it would be rejected. As Jim pointed out in #736, a large proportion of the samples are rejected because they cannot be cross-dated.

Inter-annual variability is used to select the trees that they attempt to cross-date, but it is the cross-dating that determines whether or not it gets used.

Tree 2 does share the same pattern of ring widths as the living tree, so if it had been selected because it met the variability criteria, it would be included in the chronology.

Including tree 1 in the chronology would be a false positive (because it may come from a completely different time), and doing so would have a deleterious effect on the chronology, so it is good that the cross-dating avoids that.

Excluding tree 2 from the chronology is a false negative – here is a tree that you can cross-date, but you chose not to try cross-dating because of its low variability. This matters less to the analysis – it just means you have fewer data, which is a lot better than having bad data such as tree 1.

Sorry, don’t want to labour the point. I’ll shut up now.

Yes, kudos to Mark P for making the effort, and for being willing to learn and to admit to his misunderstandings.

Naw, it’s easy, just ask McIntyre or those polymaths who wrote superfreakonomics …

(umm, that’s sarcasm folks)

I’ve been haunted by that phrase “the silence of the dendros.”

Eventually it turned into a question in my mind:

Does McI see himself as Clarice or Hannibal?

OK, it sounds like a cheap shot (and I suppose it came to me as a cheap shot, quite honestly.) But as I pondered it, it became a bit more serious, and maybe does offer a small insight into the psychology of denialism generally. Consider:

Clarice: the naive, goodhearted rookie, who outperforms seasoned veteran investigators and ends an abomination decisively?

Hannibal: the superhuman outlaw, who, despite horrific excesses, after all promulgates his own “justice,” according to his warped but nonetheless exquisitely fine-tuned perceptions–and who consistently out-manoeuvres the “professionals,” even when strait-jacketed?

Archetypes for the romanticized “rogue scientist?”

I went on to the IPCC “facts” section just now. Unfortunately it appeared to be blank.