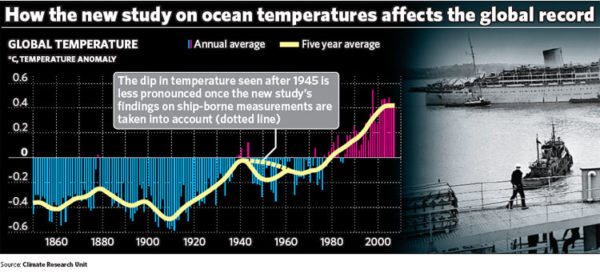

This last week has been an interesting one for observers of how climate change is covered in the media and online. On Wednesday an interesting paper (Thompson et al) was published in Nature, pointing to a clear artifact in the sea surface temperatures in 1945 and associating it with the changing mix of fleets and measurement techniques at the end of World War II. The mainstream media by and large got the story right – puzzling anomaly tracked down, corrections in progress after a little scientific detective work, consequences minor – even though a few headline writers got a little carried away in equating a specific dip in 1945 ocean temperatures with the more gentle 1940s-1970s cooling that is seen in the land measurements. However, some blog commentaries have gone completely overboard on the implications of this study in ways that are very revealing of their underlying biases.

The best commentary came from John Nielsen-Gammon’s new blog where he described very clearly how the uncertainties in data – both the known unknowns and unknown unknowns – get handled in practice (read that and then come back). Stoat, quite sensibly, suggested that it’s a bit early to be expressing an opinion on what it all means. But patience is not one of the blogosphere’s virtues and so there was no shortage of people extrapolating wildly to support their pet hobbyhorses. This in itself is not so unusual; despite much advice to the contrary, people (the media and bloggers) tend to weight new individual papers that make the news far more highly than the balance of evidence that really underlies assessments like the IPCC. But in this case, the addition of a little knowledge made the usual extravagances a little more scientific-looking and has given it some extra steam.

Like almost all historical climate data, ship-board sea surface temperatures (SST) were not collected with long term climate trends in mind. Thus practices varied enormously among ships and fleets and over time. In the 19th Century, simple wooden buckets would be thrown over the side to collect the water (a non-trivial exercise when a ship is moving, as many novice ocean-going researchers will painfully recall). Later on, special canvas buckets were used, and after WWII, insulated ‘buckets’ became more standard – though these aren’t really buckets in the colloquial sense of the word as the photo shows (pay attention to this because it comes up later).

The thermodynamic properties of each of these buckets are different and so when blending data sources together to get an estimate of the true anomaly, corrections for these biases are needed. For instance, the canvas buckets give a temperature up to 1ºC cooler in some circumstances (that depend on season and location – the biggest differences come over warm water in winter, global average is about 0.4ºC cooler) than the modern insulated buckets. Insulated buckets have a slight cool bias compared to temperature measurements that are taken at the inlet for water in the engine room which is the most used method at present. Automated buoys and drifters, which became more common in recent decades, tend to be cooler than the engine intake measures as well. The recent IPCC report had a thorough description of these issues (section 3.B.3) fully acknowledging that these corrections are a work in progress.

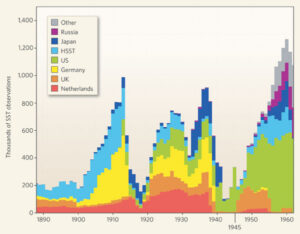

And that is indeed the case. The collection and digitisation of the ship logbooks is a huge undertaking and continues to add significant amounts of 20th Century and earlier data to the records. This dataset (ICOADS) is continually growing, and the impacts of the bias adjustments are continually being assessed. The biggest transitions in measurements occurred at the beginning of WWII between 1939 and 1941 when the sources of data switched from European fleets to almost exclusively US fleets (and who tended to use engine inlet temperatures rather than canvas buckets). This offset was large and dramatic and was identified more than ten years ago from comparisons of simultaneous measurements of night-time marine air temperatures (NMAT) which did not show such a shift. The experimentally-based adjustment to account for the canvas bucket cooling brought the sea surface temperatures much more into line with the NMAT series (Folland and Parker, 1995). (Note that this reduced the 20th Century trends in SST).

More recent work (for instance, at this workshop in 2005), has focussed on refining the estimates and incorporating new sources of data. For instance, the 1941 shift in the original corrections, was reduced and pushed back to 1939 with the addition of substantial and dominant amounts of US Merchant Marine data (which mostly used engine inlets temperatures).

The version of the data that is currently used in most temperature reconstructions is based on the work of Rayner and colleagues (reported in 2006). In their discussion of remaining issues they state:

Using metadata in the ICOADS it is possible to compare the contributions made by different countries to the marine component of the global temperature curve. Different countries give different advice to their observing fleets concerning how best to measure SST. Breaking the data up into separate countries’ contributions shows that the assumption made in deriving the original bucket corrections—that is, that the use of uninsulated buckets ended in January 1942—is incorrect. In particular, data gathered by ships recruited by Japan and the Netherlands (not shown) are biased in a way that suggests that these nations were still using uninsulated buckets to obtain SST measurements as late as the 1960s. By contrast, it appears that the United States started the switch to using engine room intake measurements as early as 1920.

They go on to mention the modern buoy problems and the continued need to work out bias corrections for changing engine inlet data as well as minor issues related to the modern insulated buckets. For example, the differences in co-located modern bucket and inlet temperatures are around 0.1 deg C:

(from John Kennedy, see also Kent and Kaplan, 2006).

However it is one thing to suspect that biases might remain in a dataset (a sentiment shared by everyone), it is quite another to show that they are really have an impact. The Thompson et al paper does the latter quite effectively by removing variability associated with some known climate modes (including ENSO) and seeing the 1945 anomaly pop out clearly. In doing this in fact, they show that the previous adjustments in the pre-war period were probably ok (though there is substantial additional evidence of that in any case – see the references in Rayner et al, 2006). The Thompson anomaly seems to coincide strongly with the post-war shift back to a mix of US and UK ships, implying that post-war bias corrections are indeed required and significant. This conclusion is not much of a surprise to any of the people working on this since they have been saying it in publications and meetings for years. The issue is of course quantifying and validating the corrections, for which the Thompson analysis might prove useful. The use of canvas buckets by the Dutch, Japanese and some UK ships is most likely to blame, and given the mix of national fleets shown above, this will make a noticeable difference in 1945 up to the early 1960s maybe – the details will depend on the seasonal and areal coverage of those sources compared to the dominant US information. The schematic in the Independent is probably a good first guess at what the change will look like (remember that the ocean changes are constrained by the NMAT record shown above):

Note that there was a big El Niño event in 1941 (independently documented in coral and other records).

So far, so good. The fun for the blog-watchers is what happened next. What could one do to get the story all wrong? First, you could incorrectly assume that scientists working on this must somehow be unaware of the problems (that is belied by the frequent mention of post WWII issues in workshops and papers since at least 2005, but never mind). Next, you could conflate the ‘buckets’ used in recent decades (as seen in the graphs in Kent et al 2007‘s discussion of the ICOADS meta-data) with the buckets in the pre-war period (see photo above) and exaggerate how prevalent they were. If you do make those mistakes however, you can extrapolate to get some rather dramatic (and erroneous) conclusions. For instance, that the effect of the ‘corrections’ would be to halve the SST trend from the 1970s. Gosh! (You should be careful not to mention the mismatch this would create with the independent NMAT data series). But there is more! You could take the (incorrect) prescription based on the bucket confusion, apply it to the full global temperatures (land included, hmm…) and think that this merits a discussion on whether the whole IPCC edifice had been completely undermined (Answer: no). And it goes on – once the bucket confusion was pointed out, the complaint switched to the scandal that it wasn’t properly explained and well, there must be something else…

All this shows wishful thinking overcoming logic. Every time there is a similar rush to judgment that is subsequently shown to be based on nothing, it still adds to the vast array of similar ‘evidence’ that keeps getting trotted out by the ill-informed. The excuse that these are just exploratory exercises in what-if thinking wears a little thin when the ‘what if’ always leads to the same (desired) conclusion. This week’s play-by-play was quite revealing on that score.

[Belated update: Interested in knowing how this worked out? Read this.]

Neil B., Consider that Mars is about 1.5 times further from the sun than Earth. Jupiter is over 5.2 times as far. There is a climate model for Mars–and one of the biggest factors is prevalence of dust storms, which block the sun. Guess what. The period during which they say there was warming is free of these storms. Factor this in, and the warming is explained according to the model.

In the case of Jupiter, most of its energy comes from within the planet, not from the Sun.

Anyone using this argument is either ignorant or a fraud (I will let Richard Lindzen and your cartoonist decide which represents the lesser charge).

Neil B., click “Start Here” at top of page,

page down to the links under the heading:

“Informed, but seeking serious discussion of common contrarian talking points:

“All of the below links have indexed debunks of most of the common points of confusion….”

You’ll find the Mars/Jupiter stuff there.

2000 EPA carbon dioxide plan. Can anyone help?

In response to the year-old Supreme Court order directing the EPA to regulate carbon dioxide emissions, the EPA plans to open up a listening session and send the issue out for public comment before any draft regulations are proposed. It is contrary to EPA’s mission to suggest that they don’t know what to do. EPA’s job is to write detailed regs and send them out for public comment.

In December 2000 (?) EPA had an outline of proposed CO2 regs on their web page. I didn’t print it because that was before EPA scrubbed information from their web site. Now the site contains notes that certain documents are not updated but are kept for archival purposes. Not available.

Does anyone have this information? My vague recollection is that it might have been a powerpoint pdf. I think it would be useful to resurrect it and point out that EPA does, indeed, know what to do.

Thanks.

Re #253

Try googling for the wayback machine, I’m unable to post the url because this site thinks it’s spam.

minor correction, Laine: I think the Court declared that the EPA had the authority to regulate CO2 emissions, not that they had to. (and FWIW, even with that was not the first time by a long shot the Court was wrong.)

“…the Court was wrong” (relative to EPA having the authority to regulate CO2 emissions).

Oh brother. That is absolutely preposterous and fundamentally wrong. There is absolutely no basis whatsoever for that statement. EPA has had the authority to regulate specific pollutants for decades. Based on scientific studies, specific criteria are set for sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, fine particles, ozone, lead and nitrogen oxides. See http://www.epa.gov/air/criteria.html. And contact your local state environmental agency for details. You may learn something about “non-attainment” areas.

re: 256. Correction. Oops, wrong URL. That should have been http://www.epa.gov/air/urbanair/.

Dan, your own good reference specifies the specific pollutants that the EPA is charged with managing and regulating under the Clean Air Act and revisions. You’ll notice CO2 is not one of them. It is true that the EPA can and has selected other things to monitor, CO2 being one, but they need to get some legal authority/directive to manage and regulate (in most cases) other things — which they have done in the past, but not for CO2. Those additional things were substances that were very similar to the “pollutants” as described in the legislation like radon or most being like the loose-goosey “particulate matter”.

At least that is how the EPA saw it; so that must make them also “absolutely preposterous and fundamentally wrong.” The Court, in my opinion, simply thought it sounded like a good idea and ordered the EPA to look at it — Clean Air Act et al having little to do with it. Though that admittedly is a bit overstated as, as my main point said, the Court ordered the EPA to assess regulation, not to actually do it, which, if you’re looking for tiny loopholes (or as Chief Justice Roberts in dissent called it, a “sleight of hand”), was not totally contrary to legislation.

Rod B, Section 160 of the Clean Air Act requires: “to protect public health and welfare from any actual or potential adverse effect which in the Administrator’s judgment may reasonably be anticipate to occur from air pollution or from exposures to pollutants in other media…”

As climate change certainly entails adverse effect to public health and welfare, the cause of that change needs to be regulated per this provision.

re: 258. You are using circular reasoning now re: the Clean Air Act having nothing to do with it. Wrong. The legal precedent is set by the Clean Air Acts (there have been several amendments). Section 160.

BTW, “particulate matter” is not “loose-goosey”. It is called “science”. There were specific, updated scientific studies related to public health and welfare exposure which went into the setting of the particulate matter criteria standards. In fact, the fine particulate standard was recently revised based on updated health studies.

Ray, the anomaly is that CO2 has never been viewed as “pollution” by the commonly, scientifically, and long-held definition. It was only through the dummying down of the definition that the advocates could sneak through the now new loophole and include CO2. It was proclaimed loud and long enough that it pretty much took and CO2 is now, without a lot of discriminating thought, kinda accepted as a pollution. But it was not meant nor contemplated by the Act.

Dan, “nothing to do with it” is probably an editorial exaggeration, but it is the thinking of the Justices that I am referring to, not the Act(s) itself. Acts set legalities. They do not set precedent per se; only when the judiciary wants to expand the law to what they would like can law be viewed as a precedent.

By loose-goosey I simply meant that it can cover a multitude of sins vs. the specificity of the other pollutants. It can be misused IMO but is probably a reasonable flexibility.

[Response: I’m not a lawyer, but the contortions of the language of the act made by advocates for the “CO2 is not pollution” crowd were very weak. The CAA has clear language (sections g and h) defining a pollutant to be something that is emitted into the air and can affect welfare – specifically air quality, water quality or climate. You have to be a medieval theologian to argue that this does not include CO2. – gavin]

Hello again,

Here’s a link to the Court’s decision. Although it’s lengthy, the decision is summarized in the first few pages.

There are probably things we could debate but this sentence says a lot to me: “Because greenhouse gases fit well within the Act’s capacious definition of ‘air pollutant’, EPA has statutory authority to regulate emission of such gases from new motor vehicles.” The precedent is set. The Court rejected the EPA’s argument that carbon dioxide is not a pollutant, an argument based on its not being a traditional i.e. toxic air pollutant in the usual sense. The Court also rejected the EPA’s argument that this is not a good time to regulate GHGs.

Can EPA seriously claim that they need pre-proposal comments because they don’t know what to do? It’s an invitation to those with the time, money and awareness to come forward and write the regs. John/Jane Doe aren’t going to respond to this request yet they are still entitled to EPA’s protection and oversight. EPA can hire anyone to compile comments but it’s my understanding that the agency employs scientists and engineers for a purpose.

This unusual regulatory procedure also slows the process down considerably. I’m sure everyone here is aware of Dr. Hansen’s most recent congressional testimony. He works tirelessly to bring this issue to policymakers at great personal cost and his tone becomes more urgent with each appearance.

Laine

http://www.supremecourtus.gov/opinions/06pdf/05-1120.pdf

Laine V (#253) There were no proposed CO2 regulations in 2000. The EPA could do that only after they made a formal finding that CO2 fit the definition of pollutant under the Clean Air Act (CAA). Considering that once a substance is listed as a pollutant the CAA requires it to be regulated, there would have been lots of attention and news stories.

If there was anything on the EPA site it was probably just a page with information about the effects of greenhouse gases and discussion of possible regulations. Anything like a proposed regulation would be in the recorded in the Federal Register.

# 261 In the Supreme Court case the issue was not about the question of CO2 meeting the definition of pollutant under the Clean Air Act. As Gavin correctly notes the language of the CAA requires CO2 to be listed as a pollutant.

The EPA and its allies (auto makers, conservative political groups, et al) in this lawsuit never tried to argue that CO2 was not a pollutant because that position had no basis and would never work. The EPA argued that there were other considerations that trumped the CAA, but this did not get much traction. The EPA also argued that for technical reasons the states and their allies (cities, enviro groups, et al) did not have the right to challenge the EPA’s decision in court. This argument did have some validity, enough to get a strong dissent, but not for the court to allow the EPA’s decision to stand.

Gavin, Neither am I a lawyer (though might be a “wannabe” ;-) ), but I recall a rule of lawyers that says the legal answer to any question is, “Maybe yes. Maybe no.”

I’ll try to respond, but briefly so as to not totally mess up this thread. Is your reference an explicit implication that stuff like CO2 is something the Congress had in mind for possible regulation by the EPA? Or is it just a broad general almost throw-away statement similar to, ‘the purpose of the EPA is to regulate stuff going into the air and water’? How might it relate to an earlier (Sec 112, part b) passage that reads (paraphrasing with my emphasis), “The Administrator will review the [very long specific] list and….add pollutants which present through inhalation or other routes of exposure a threat of adverse human health effects (including….carcinogenic, mutagenic, teratogenic, neurotoxic, cause reproductive dysfunction, or are acutely or chronically toxic)….” Or the definition: “(6) HAZARDOUS AIR POLLUTANT.— ….any air pollutant listed [as above]”

I can see how the answer is debatable and might go either way. But it seems relevant that, to the best of my knowledge and search, CO2 is not stated, mentioned, implied, nor hinted at anywhere in the statute, save one mention of the EPA looking at CO2 as a consultant in conjunction with a whole subsection that directs the National Academy of Science and the OSTP (specifically not the EPA) to conduct a broad study of CO2 — and gave them a whopping $3,000,000 to do it. Doesn’t seem to be an even minor focus or intent. (Though I recognize understand some in Congress would like it; they just did not get it in the Act.)

Laine repeats my assertion — the Court didn’t like the way CAA read and decided what they would like.

Sorry for all this legalese, but with Hanson wanting to criminally indict the CEO of Exxon et al, it’s starting to get significant.

To all of you salivating over the prospects of the EPA directly regulating CO2 emissions (not to mention methane, nitrates, and water emissions coming right behind), I would respectfully suggest you be very cautious and think through what you wish for, as the Chinese say.

Rod B, I think you are applying the strictures of constructionist constitutional law to an act of Congress. This is invalid, since Congress chose to include language sufficiently broad that it could be applied to pollutants not identified at the time the act was written. If it affects public welfare, it is a pollutant–and no amount of propaganda claiming “CO2 is fertilizer” will change that. I would contend that it’s the propaganda that is fertilizer.

Joseph (#263)

Yes, I know the procedure. There were no proposed regulations. When I made my request for information, I described it as an outline for lack of a better word. My point was to challenge the notion that the procedure you correctly describe cannot be followed in this case because EPA needs prior public input before writing regs. The document I vaguely recalled would have been useful in this regard but is certainly not necessary to support my premise. In any case, I appreciate all responses and recognize that this is primarily a science page and a valuable one. I wasn’t attempting to hijack the thread with politics. Cheers.

Laine V try the Warming Law Blog. The lawyers there have insightful commentary on the legal/political issues. They have a recent post that might help with your request for information.

http://warminglaw.typepad.com/my_weblog/2008/05/insulted-epa-fi.html

#265 (Ray Ladbury), #264 (Rod B.) et al

The Clean Air Act contains broad powers to regulate substances emitted into the air and gives the EPA little discretion on when to regulate when certain conditions are met. A plain reading of the entire law demonstrates this. Its a long established legal principal, very dear to conservative judges and legal scholars, that when a statute is clear then discussions of Congress’ intent or the wisdom of the statute are irrelevant.

In Mass v EPA the only real question was whether the plaintiffs had the right to go to court to overturn the EPA’s decision. The “sleight of hand” mentioned by Justice Roberts was addressing the majorities expansion of the right of state governments to challenge agency decisions in court.

This is my last comment on this subject. I’ll claim res judicata on any further discussion.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Res_judicata