Regional Climate Projections in the IPCC AR4

The climate projections presented in the IPCC AR4 are from the latest set of coordinated GCM simulations, archived at the Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison (PCMDI). This is the most important new information that AR4 contains concerning the future projections. These climate model simulations (the multi-model data set, or just ‘MMD’) are often referred to as the AR4 simulations, but they are now officially being referred to as CMIP3.

One of the most challenging and uncertain aspects of present-day climate research is associated with the prediction of a regional response to a global forcing. Although the science of regional climate projections has progressed significantly since last IPCC report, slight displacement in circulation characteristics, systematic errors in energy/moisture transport, coarse representation of ocean currents/processes, crude parameterisation of sub-grid- and land surface processes, and overly simplified topography used in present-day climate models, make accurate and detailed analysis difficult.

I think that the authors of chapter 11 over-all have done a very thorough job, although there are a few points which I believe could be improved. Chapter 11 of the IPCC AR4 working group I (WGI) divides the world into different continents or types of regions (e.g. ‘Small islands’ and ‘Polar regions’), and then discusses these separately. It provides a nice overview of the key climate characteristics for each region. Each section also provides a short round up of the evaluations of the performance of the climate models, discussing their weaknesses in terms of reproducing regional and local climate characteristics.

Africa.

The report asserts that the extent to which regional models can represent the local climate is unclear and that the limitation of empirical downscaling is not fully understood. It is nevertheless believed that land surface feedbacks have a strong effect on the regional climate characteristics.

For the future scenarios, the median value of the MMD GCM simulations (SRES A1b) yields a warming of 3-4C between 1980-1999 and 2080-2099 for the four different seasons (~1.5 times the global mean response). The GCMs project an increase in the precipitation in the tropics (ITCZ)/East Africa and a decrease in north and south (subtropics).

Europe and the Mediterranean.

A more detailed picture was drawn on the results from a research project called PRUDENCE, which represents a small number of TAR GCMs. The time was too short for finishing new dynamical downscaling on the MMD.

The PRUDENCE results, however, are more appropriate for exploring uncertainties associated with the regionalisation, rather than providing new scenarios for the future, since the downscaled results was based on a small selection of the GCMs from TAR.

Therefore, I was surprised to see such an extensive representation of the PRUDENCE project in this chapter, compared to other projects such as STARDEX and ENSEMBLES. (One explanation could be that the STARDEX results are used more in WGII, although apparently not cited. The results from ENSEMBLES are not yet published, and besides STARDEX is mentioned twice in section 11.10.)

There are some results for Europe presented in chapter 11 of IPCC AR4 which I find strange: In Figure 11.6 the RCAO/ECHAM4 from the PRUDENCE project yields an increase in precipitation up to 70%(!) along the west coast of mid-Norway. Much of this is probably due to an enhanced on-shore wind due to a systematic lowering of the sea level pressure in the Barents Sea, and an associated orographic forcing of rain.

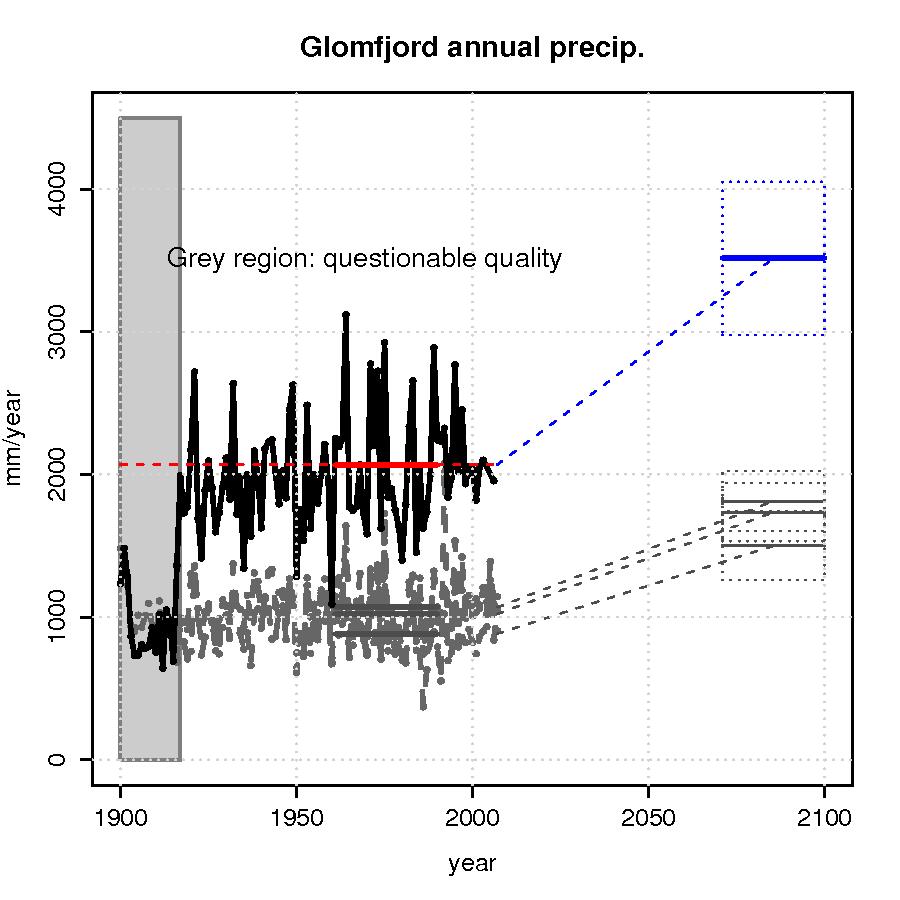

The 1961-90 annual total precipitation measured at the rain gauge at Glomfjord (66.8100N/13.9813E; 39 m.a.s.l.) is 2069 mm/year, and a 70% increase will therefore imply an increase to 3500mm/year (Left figure) which in my opinion is unrealistic . Apart from a sudden jump in the early part of the Glomfjord record, there are no clear and prominent trends in the historical time series (Figure left). The low values in the early part are questionable as the neighbouring station series do not exhibit similar jumps/breaks and is probably a result of a relocation of the rain gauges.

An increase of annual rainfall exceeding 1000mm would imply either that evaporation from the Norwegian Sea area must increase dramatically, or the moisture convergence must increase significantly since the water must come from somewhere. However, the whole region is already a wet region (as indicated by the annual rainfall totals) in the way of the storm tracks.

There are large local variations here (see grey curves in left Figure for nearby stations) and Glomfjord is a locations with high annual rainfall compared to other sites in the same area, but even a 70% increase of the rainfall with annual totals exceeding 1000mm at nearby sites (adjacent valleys etc) is quite substantial.

However, one may ask whether the rainfall at Glomfjord may change at a different rate to that of its surroundings. This question can only be addressed with empirical-statistical downscaling (ESD) at present, as RCMs clearly cannot resolve the spatial scales required.

To be fair, another PRUDENCE scenario presented in the same figure, but based on the HadAM3H model rather than the ECHAM4, suggests an upper limit for precipitation increase over northern Europe of 20% over northern Sweden.

Asia.

The Asian climate is also influenced by ENSO, but uncertainties in how ENSO will be affected by AGW cascades to the Asian climate.

There are, however, indications that heat waves will become more frequent and more intense. Furthermore, the MMD models suggest a decrease in the December-February precipitation and an increase in the remaining months. The models also project more intense rainfall over large areas in the future.

North America.

The MMD results project strongest winter-time warming in the north and summer-time warming in the southwest USA. The annual mean precipitation is, according to AR4, likely to increase in the north and decrease in southwest.

A stronger warming over land than over sea may possibly affect the sub-tropical high-pressure system off the west coast, but there are large knowledge gaps associated with this aspect.

The projections are associated with a number of uncertainties concerning dynamical features such as ENSO, the storm track system (the GCMs indicate a pole-ward shift, an increase in the number of strong cyclones and a reduction in the medium strength storms poleward of 70N & Canada), the polar vortex (the GCMs suggest an intensification), the Great Plains low-level jet, the North American Monsoon system, ocean circulation and the future evolution in the snow-extent and sea-ice. Some of these phenomena are not well-represented by the GCMs, as their spatial resolution is too coarse. The same goes for tropical cyclones (hurricanes), for which the frequency, intensity and track-statistics remain uncertain.

A number of RCM-based studies provide further regional details (North American Regional Climate Change Assessment Program). Despite improvements, AR4 also states that RCM simulations are sensitive to the choice of domain, the parameterisation of moist convection processes (representation of clouds and precipitation), and that there are biases in the RCM results when GCM are provided as boundary conditions rather than re-analyses.

Furthermore, most RCM simulations have been made for time slices that are too short to provide a proper statistical sample for studying natural variability. There are no references to ESD for North America in the AR4 chapter except for in the discussion on the projections for the snow.

Latin America.

The projections of the seasonal mean rainfall statistics for eg the Amazon forest are highly uncertain. One of the greatest sources of uncertainty is associated with how the character of ENSO may change, and there are large inter-model differences within the MMD as to how ENSO will be affected by AGW. Furthermore, most GCMs have small signal-to-noise ratio over most of Amazonia. Feedbacks from land use and land cover (including carbon cycle and dynamic vegetation) are not well-represented in most of the models.

Tropical cyclones also increase the uncertainty for Central America, and in some regions the tropical storms can contribute a significant fraction to the rainfall statistics. However, there has been little research on climate extremes and projection of these in Latin America.

According to AR4, deficiencies in the MMD models have a serious impact on the representation of local low-latitude climates, and the models tend to simulate ITCZs which are too weak and displaced too far to the south. Hence the rainfall over the Amazon basin tends to be under-estimated in the GCMs, and conversely over-estimated along the Andes and northeastern Brazil.

There are few RCM-simulations for Latin America, and those which have been performed have been constrained by short simulation lengths. The RCM results tend to be degraded when the boundary conditions are taken from GCMs rather than re-analyses. There is, surprisingly, no reference to ESD-based studies from Latin America, despite ESD being much cheaper to carry out and length of time interval being not an issue (I’ll comment on this below).

Australia & New Zealand.

The MMD projections for the monsoon rainfall show large inter-model differences, and the model projections for the future rainfall over northern Australia are therefore considered to be very uncertain.

Little has been done to asses the MMD skill over Australia and New Zealand, although analysis suggest that the MMD models in general have a systematic low-pressure bias near 50S (hence a southward displacement of the mid-latitude westerlies). The simulated seas around Australia has a slight warm bias too, and most models simulate too much rainfall in the north and too little on the east coast of Australia.

The quality of the simulated variability is also reported to be strongly affected by the choice of land-surface model.

The projections of changes is the extreme temperatures for Australia and New Zealand has followed a simple approach where the range of variations has been assumed to be constant while the mean has been adjusted according the the GCMs, thus shifting the entire statistical distribution. The justification for this approach is that the effect on changes in the range of short-term variations has been found to be small compared with changes in the mean.

Analysis for rainfall extremes suggest that the return period for extreme rainfall episodes may halve in late 21st century, even where the average level to some extent is diminishing. AR4 anticipates an increase in the tropical cyclone (TC) intensities, although there is no clear trends in frequency or location.

Furthermore, TCs are influenced by ENSO, for which there are no clear indications for the future behaviour. AR4 also states that there may be up to 10% increases in the wind over northern Australia.

AR4 states that downscaled MMD-based projections are not yet available for New Zealand, but such results are very much in need because of strong effects from the mountains on the local climate. High-resolution regional modeling for Australia is also based on TAR or ‘recent ‘runs with the global CSIRO glimate model. A few ESD studies by Timbal and others suggest good performance at representing climatic means, variability and extremes of station temperature and rainfall.

Polar regions.

However, the understanding of the polar climate is still incomplete, and large endeavors such as the IPY hope to address issues such as lack of decent observations, clouds, boundary layer processes, ocean currents, and sea ice.

AR4 states that all atmospheric models have incomplete parameterisations of polar cloud microphysics and ice crystal precipitation, however, the general improvement of the GCMs since TAR in terms of resolution, sea-ice modelling and cloud-radiation representation has provided improved simulations (assessed against re-analysis, as observations are sparse).

Part of the discussion about the Polar regions in AR4 relies on the ACIA report (see here , here and here for previous posts) in addition to the MMD results, but there are also some references to RCM studies (none to ESD-based work, although some ESD-analysis is embedded in the ACIA report). There has been done very little work on polar climate extremes and the projected changes to the cryosphere is discussed in AR4 chapter 10.

The models do in general provide a reasonable description of the temperature in the Arctic, with the exception of a 6-8C cold bias in the Barents Sea, due to the over-estimation of the sea-ice extent (the lack of sea-ice in the Barents Sea can be explained by ocean surface currents that are not well represented in GCMs). The MMD models suggest the winter-time NAO/NAM may become increasingly more positive towards the end of the century.

One burning question is whether is the response of the ice sheet will be enhanced calving/ice stream flow/basal melt. More snow will accumulate in Antarctica, as this ‘removes’ water from the oceans that otherwise would contribute to a global sea level rise. The precipitation in Antarctica, and hence snowfall, is projected to increase, thus partly offsetting the sea-level rise.

Small islands.

Most GCMs do not have sufficiently high spatial resolution to represent many of the islands, therefore the GCM projections really describe changes over ocean surfaces rather than land. Very little work has been done in downscaling the GCMs for the individual islands. However, there have been some ESD work for the Caribbean islands (AIACC).

Two sentences stating that ‘The time to reach a discernible signal is relatively short (Table 11.1)’ is a bit confusing as the discussion was referring to the 2080-2099 period (southern Pacific). After having conferred with the supplementary material, I think this means that the clearest climate change signal is seen during the first months of the year. Conversely when stating ‘The time to reach a discernible signal’ for the northern Pacific, probably refers to the last months of the year.

Other challenges involve incomplete understanding of some climatic processes, such as the midsummer drought in the Caribbean and the ocean-atmosphere interaction in the Indian Ocean.

Many of the islands are affected by tropical cyclones, for which the GCMs are unable to resolve and the trends are uncertain – or at least controversial.

Empirical-statistical or Dynamical downscaling?

AR4 chapter 11 makes little reference to empirical-statistical downscaling (ESD) work in the main section concerning the future projections, but puts most of the emphasis on RCMs and GCMs. It is only in Assessment of Regional Climate Projection Methods section (11.10) which puts ESD more into focus.

I would have thought that this lack of balance may not be IPCC’s fault, as it may be an unfortunate fact that there are few ESD studies around, but according to AR4 ‘Research on [E]SD has shown an extensive growth in application…’. If it were really the case that ESD studies were scarce, then it would be somewhat surprising, as ESD is quick and cheap (here, here, and here), and could have been applied to the more recent MMD, as opposed to the RCMs forced with the older generation GCMs.

ESD provides diagnostics (R2-statistics, spatial predictor patterns, etc.) which can be used to assess both the skill of the GCMs and the downscaling. I would also have thought that ESD is an interesting climate research tool for countries with limited computer resources, and it would make sense to apply ESD to for climate research and impact studies to meet growing concerns about local impacts of an AGW.

Comparisons between RCMs and ESD tend to show that they have similar skills, and the third assessment report (TAR) stated that ‘It is concluded that statistical downscaling techniques are a viable complement to process-based dynamical modelling in many cases, and will remain so in the future.’ This is re-phrased in AR4 as ‘The conclusions of the TAR that [E]SD methods and RCMs are comparable for simulating current climate still holds’.

So why were there so few references to ESD work in AR4?

I think that one reason is that ESD often may unjustifiably be seen as inferior to RCMs. What is often forgotten is that the same warnings also go for the parameterisation schemes embedded in the GCMs and RCMs, as they too are statistical models with the same theoretical weaknesses as the ESD models. AR4 does, however, acknowledge this: ‘The main draw backs of dynamical models are … and that in future climates the parameterization schemes they use to represent sub-grid scale processes may be operating outside the range for which they were designed’. However, we may be on a slippery slope with parameterisation in RCMs and GCMs, as the errors feed back to the calculations for the whole system.

Moreover, a common statement heard even among people who do ESD, is that the dynamical downscaling is ‘dynamical consistent’ (should not be confused with ‘coherent’). I question this statement, as there are issues of gravity wave drag schemes and filtering of undesirable wave modes, parameterisation schemes (often not the same in the GCM and the RCM), discretisation of continuous functions, and the conservation associated with time stepping, or lateral and lower boundaries (many RCMs ignore air-sea coupling).

RCMs do for sure have some biases,yet they are also very useful (similar models are used for weather forecasting). The point is that there are uncertainty associated with dynamical downscaling as well as ESD. Therefore it’s so useful to have two completely independent approaches for studying regional and local climate aspects, such as ESD and RCMs. One should not lock onto only one if there are several good approaches. The two approaches should be viewed as two complementary and independent tools for research, and both ought to be used in order to get a better understanding of the uncertainties associated with the regionalisation and more firm estimates on the projected changes.

Thus, the advantage of using different methods has unfortunately not been taken advantage of in chapter 11 of AR4 WGI to the full extent, which would have made the results even stronger. When this points was brought up during the review, the response from the authors of the chapter was:

This subsection focuses on projections of climate change, not on methodologies to derive the projections. ESD results are takan into account in our assessment but most of the available studies are too site- or area-specific for a discussion within the limited space that is available.

So perhaps there should be more coordinated ESD efforts for the future?

On a different note, the fact that the comments and the response are available on-line demonstrates that IPCC process is transparent indeed, showing that, on the whole, the authors have done a very decent job. The IPCC AR4 is the state-of-the-art consensus on climate change. One thing which could improve the process could also be to initiate more real-time dialog and discussion between the reviewers and the authors, in additional to the adopted one-way approach comment feed.

Uncertainties

One section in IPCC AR4 chapter 11 is devoted to a discussion on uncertainties, ranging from how to estimate the probability distributions to the introduction of additional uncertainties through downscaling. For instance, different sets of solutions are obtained for the temperature change statistics, depending on the approach chosen. The AR4 seems to convey the message that approaches based on the performance in reproducing past trends may introduce further uncertainties associated with (a) models not able to reproduce the historical (linear) evolution, and (b) the relationship between the observed and predicted trend rates may change in the future.

Sometimes the uncertainty has been dealt with by weighting different models according to their biases and convergence to the projected ensemble mean. The latter seems to focus more on the ‘mainstream’ runs.

AR4 stresses that multi-model ensembles only explore a limited range of the uncertainty. This is an important reminder for those interpreting the results. Furthermore, it is acknowledged that trends in large-area and grid-box projections are often very different from local trends within the area.

Re #139: [Reducing emissions to combat global warming is a noble cause, but its potential for success is weak. Why is it touted as the answer?]

Err… Because it’s the only thing anyone knows about that A) might work; and B) doesn’t involve killing some billions of people. Why is this so hard to understand?

Falafulu Fisi (#148)

Support vector machine gets described as a feed-forward neural network in some articles, but others speak of neural network support vector machine hybrids.

Interesting stuff.

The downscaling of precipitation is to compensate for the coarsed-grained nature of climate models. However, support vector machine is also being used for six to nine month forecasts of airstream flow, classification of images (although it would appear cloud detection can use a simple quadratic function – no need to swat a fly with a hand grenade), tornado prediction and detection, soil moisture prediction, crop yield prediction, determining correlations between aerosols and their environment, etc.. A tool to consider wherever raw data exists in a great abundance, but we might otherwise lack the resources for integrating that data into what most concerns us.

You will find a short section on statistical downscaling in Chapter 2 of Working Group II, thereby showing evidence there is more to the IPCC than Working Group I.

Chapter 2 deals with the use of climate information in impact, adaptation and vulnerability (IAV) assessments. Severe space restrictions meant that an adequate discussion of the value of methods for specific purposes is not available.

Chapter 2 also contains a useful figure (2.6) that shows that although the number of models has expanded appreciably (almost x3) the range of projected regional temperature has contracted. Rainfall is a more mixed bag.

I’m only ok with using downscaling in IAV assessments where it is warranted. Unless there is a bias, or regional detail that is consistent across a cohort of models or reasonable theoretical or observational reasons for suspecting that is the case, one is better off to explore the broad range of uncertainties directly from model output, using Bayesian methods to assess how sensitivie the results are to underlying assumptions. Of course, downscaling can be testing within the same framework, and must be if your interest is extreme rainfall and flooding, for example.

For further information on the application of different methods go here

[[Reducing emissions to combat global warming is a noble cause, but its potential for success is weak. Why is it touted as the answer?]]

Because there isn’t any other answer. Either we massively reduce CO2 emissions in the next 8-10 years, or we will trip geophysical feedbacks like seabed clathrates and permafrost GHGs that will make the problem bad enough to seriously affect human civilization.

Re 139. Michael, You seem to be assuming that future development must follow the course of past development. This is demonstrably not the case. Communications used to be dependent on phone lines and on the companies that laid them. Now, in India, everything is wireless, and many villages are free of the corrupt and inefficient state telephone monopoly. Likewise, it would make much more sense for rural villages to be able to generate their own power from photovoltaics rather than waiting for the grid to reach out to them. In Brazil, which has a model rural electrification project, it made more sense to bring in deisel fuel by boat rather than string wires to remote villages. The main obstacle to using solar instead is the lack of good, inexpensive storage technologies–probably not an insurmountable technical obstacle.

Even if they are very energy efficient, developing economies will likely increase energy consumption as they develop. It is largely up to the technologically advanced countries whether that increase will cause a rise in ghg emissions or whether we will assist developing nations in implementing carbon-neutral strategies.

Barton,

How likely is it that we would release the carbon in the clathrates? Since they are in the deep cold ocean, it would take quite awhile before they would become unstable, I would think. It is a huge heat reservoir and heat transport to the ocean depths is quite slow (one reason why the atmosphere heats up so quickly). I’m afraid the permafrost if probably a done deal, along with decreased solubility of CO2 in warmer surface waters.

Re #142 Michael: [when planning for global warming, it would be detrimental to assume humanity would suddenly mobilize like we’ve never mobilized in history.]

I’m not assuming it, nor have I seen anyone here doing so. I most certainly am saying we must do it, or risk catastrophe. Nor do I think it impossible: now is not like any other time in history, both because all those with an interest in what happens more than 20-30 years in the future now have, objectively, a vital common interest in cutting emissions; and because the institutional structures and communications technologies we have available for mobilisation are unparalleled. In fact, however, we have seen the intensity of mobilisation we need on transnational and “transideological” scales before – in World War 2.

You seem strangely shy of bringing out your alternative to working for fast and deep emissions cuts. If it’s just “Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die.” OK, there are plenty who will join you, but why waste your time on this board? If it’s something else, let us into the secret. We’d love to have a feasible alternative, or complementary strategy.

Michael wrote:

You assert this but offer no reason why it must be true. Certainly some developing countries are increasing their GHG emissions as they develop, notably China and India. But this is the result of their decisions to develop along environmentally unsound, unsustainable energy technology paths, eg. building large numbers of coal-fired electrical generation plants. But this development path not only threatens the entire world with climate change, it threatens the very economic development that it ostensibly enables. This is well understood in China, where the environmental effects of increased pollution from burning coal, and indeed from global warming, are already having severe negative effects on economic development.

There are alternative climate-friendly energy development paths available to both China and India that don’t have these negative consequences for the Earth’s climate or for those countries’ long-term economic development that are the subject of much discussion in both countries, particularly in China where the central government is seriously engaged in promoting clean & sustainable economic development through energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies.

And in other parts of the developing world which have even greater need for energy, such as southern Africa, and for that matter rural areas of India and China, conventional GHG-intensive energy production, such as large scale electrical grids powered by large centralized coal or nuclear power plants, are not even a possibility. There is no money available to construct such systems. That’s why small-scale distributed photovoltaic electricity generation is growing exponentially in the developing world.

Essentially, you are begging the questions of the extent to which improving human well-being in the developing world depends on increased energy production and consumption, and whether such increased energy production necessarily requires increased GHG emissions. You argue that it does, but the only evidence you offer to support that argument is the assertion that it does.

Michael wrote:

Again, you assert this but offer no reason why it must be true. As others have pointed out, the references to “education” and “medical services” are non sequiturs — there is no link between either education or medical services and increased energy use, let alone increased GHG emissions. And as others have also pointed out, much poverty in the developed world is rooted in inequitable distribution of existing resources, rather than an actual shortage of resources, and the solutions are social and political — neither of which produce more GHG emissions.

Michael wrote:

What other answer is there? What other answer do you propose? It may be that the likelihood that humanity as a whole will actually reduce GHG emissions enough, soon enough, to avert a global climate cataclysm is small. I tend to think so, particularly given that GHG emissions continue to not only increase but are accelerating. But as others have pointed out, there is no other answer. If humanity chooses not to reduce emissions, that won’t make some other easier answer magically appear. It will lead to global catastrophe.

One last comment about this line of argument. The argument that efforts to mitigate global warming by reducing GHG emissions will prevent economic growth in the developing world and thus harm millions of poor people is spurious. Every international body concerned with improving the well-being of poor people in the developing world, eg. the Millennium Development Goals, has said that such efforts will be undermined and thwarted by the effects of global warming. Regional climate projections (the topic of this thread) strongly suggest that billions of poor people in the developing world will suffer the most from the effects of global warming. Reducing GHG emissions is the ONLY available way to mitigate anthropogenic global warming and doing so is therefore essential to any hopes of improving the well being of people in the developing world, not a hindrance to it.

But what is even MORE spurious is that this argument is often offered as a justification for rich countries to continue emitting GHGs. The argument seems to be that (1) poor people in the developing world need more energy in order to have more economic development and improve their well-being, and (2) producing this additional energy will necessarily entail increasing GHG emissions from developing countries, therefore (3) rich people in the USA and other rich countries should continue driving SUVs, living in poorly-insulated McMansions, etc.

That is absurd. Anyone in the USA who really cares about the well-being of people in the developing world and accepts points (1) and (2) above — and I reject point (2) — should embrace the opposite of point (3), and insist that if economic growth in the developing world necessarily will result in increased GHG emissions, then people in the rich world have all the more reason to do whatever is necessary to reduce their own GHG emissions.

Chris Dudley(149) — Thank you.

Nigel Williams(147) — Use bio-fuels. The pyrolysis produces such as well as char. And actually, I am thinking of an even larger scale sequestration than you mention, about 2 Gt of carbon for every 1 Gt of fossil carbon burned.

The char need not be worked into the soils. Bury it in abandoned mines, even open-pit ones.

Anyway, I do encourage you to follow

http://biopact.com

Maybe even better is biocoal, via hydrothermal carbonisation:

http://biopact.com/2007/05/green-designer-coal-more-on.html

> clathrates? Since they are in the deep cold ocean,

> it would take quite awhile before they would become unstable

Til the oceans are about as warm as they were at the end of the last ice age, it appears. At which point if ocean pH hadn’t already killed off much of the plankton, the big jump in methane could. Large consequence event, as I read what’s available.

http://ethomas.web.wesleyan.edu/ees123/clathrate199.htm

As I read it, methane is bubbling out now, probably reached a peak rate of emission at the end of the last ice age and had started to simmer down as the ocean began to cool down and allow more clathrate to form than bubbled off — it’s a continuous process, with a rate reversal some 10,000 years ago — but as we warm the surface water and permafrost up past where it was 10k years ago, we can expect more emission. Look at the pages mentioning the Storegga slide.

This is really new stuff.

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2005/12/methane-hydrates-and-global-warming/

http://geosci.uchicago.edu/~archer/reprints/buffett.2004.clathrates.pdf

Here’s a nice paper showing how areas where methane is bubbling to the surface can be studied — a remotely operated vehicle visited pockmarks on the seafloor. Fig.6 shows sonar scans of the mud below show areas where columns of gas are rising through the sediment that haven’t yet broken the surface to create further pockmarks

http://www.martech-institute.org/site/index.php?id=63

Ray Ladbury (#156) wrote:

There are shallow water methane hydrates, particularly up north, Siberia for example. Some just below freezing. A degree will make a difference for some of it, but it should be gradual. And it is certainly worth keeping in mind that whatever gets leaked has a half-life of about 40 years before degrading to CO2.

This has some on it:

Rasslin’ swamp gas

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2006/10/rasslin-swamp-gas/

However, some are showing up at much shallower depths than expected off of Canada:

Timothy Chase said…

A tool to consider wherever raw data exists in a great abundance.

That’s true. Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a very popular algorithm in the domain of Machine Learning (ML). It is widely adopted in different areas such as speech recognition, robotics, spam-filter, search engine, image processing, data classification (pattern recognition), data approximation (regression), computer network intrusion detection, data-mining, text-mining and many more. It is only recent that I have noted that the research communities in climate science have picked up on it and start using it for analysis. SVM has been around since the early 1990s. Also, the majority of the statistics community haven’t picked up on it yet.

There are lots of different algorithms in ML that would be of interest to climate modeling, but I think that climate researchers have not picked up on some of those algorithms yet. Eg, PCA (principle component analysis) is a linear method and it is still the popular method for climate data analysis today, however there is a more robust version which is called k-PCA (kernel PCA), a non-linear method and this algorithm has been available in the journal of machine learning since 1998.

The Journal of Machine Learning Research (JMLR) have made all their papers freely available online to download.

“Journal of Machine Learning Research”

http://jmlr.csail.mit.edu/papers/

Here is another popular freely downloadable research papers in machine learning, from the “Neural Information Processing Systems” (NIPS). You can click on any volume from any year to download a title that might of interest.

“Neural Information Processing Systems”

http://books.nips.cc/

Occasionally, I see some papers related to climate modeling and data-analysis that are being published in the machine learning literatures, prior to being picked up in climate research journals. Eg, a popular algorithm in machine learning called ICA (independent component analysis), a linear method that has been available in the machine learning literatures since the early 1990s, but researchers in climate had just picked up on it over recent years, such as the following paper (see link below). Again, ICA hasn’t penetrated the statistics literatures yet. It is still not widely known in the statistics community yet.

“Rotation of EOFs by the Independent Component Analysis: Toward a Solution of the Mixing Problem in the Decomposition of Geophysical Time Series.”

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002JAtS…59..111A

The links for JMLR and NIPS free resources are useful links for climate researchers.

Re 132

I have not gone through all agrichar/biochar info, but I am certainly not seeing anything like the kind of environmental impact statemant required for a rational consideration of broad public policy. I have not even been able to find a good analysis of the products.

See http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/phs69.html and read on to sources of PAH

Third world countries have an increasing GHG graph as they develop and decrease their poverty. I agree there are many cases where a developing society can cause a reduction in GHG emissions. But the rule is: less poverty equals in increase in GHG’s, by far. Less poverty leading to a decrease in GHG’s is the exception, by far.

Education and medical facilities don’t need big industry, but as a rule they support and are supported by big industry. Facilities for a minor education can include water, sewer, electrical services, construction and architecture for the building, publishers for textbooks, equipment for clearing and grading land for playing fields, transportation for the students, fire and police services, sources for basic scientific instruments, etc.

All you really need is a teacher, a student, and maybe a pad and pencil, find a spot under an oak tree in a field, and you could do the job. But this is not always reality. It is rarely the reality. And even if it starts out this way, it has the tendency toward more students, and a better, safer study environment. The worldwide average primary school is responsible for significant GHG’s. A secondary school even more so. Understand there are shining examples of how large schools can have very low GHG emissions. But this is how it SHOULD be done, not how it IS done.

Before I say anything else, SecularAnimist, do you have any general objections to these generalities?

>>Falafulu Fisi Says:

3 September 2007 at 8:33 PM

>I am starting to think that RealClimate regards me as either a pain in the ass or a threat in the debate >here.

Falafulu, please publish your work in peer-reviewed journals if you think you have new evidence.

Otherwise, your arguments are specious (err, eg. speculative and unsubstantiated, and quite useless). This is not the place to bring up scientific debate (there’s no one here to referee for deliberate falsehoods or scientifically flawed, weak thinking)…my teen niece’s comments have as much value as yours on this subject in this medium.

…And yes, contrary ideas are published (if they have merit) in the peer-reviewed literature such as Lindzen’s “iris effect” and Von Storch’s question about part of the “hockey stick” (both of which were

found to be scientifically unviable).

Aaron Lewis(161) — Thank you. I have placed an inquiry with the DoE EERE (Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy) Biomass Program. Also, there is a bit of information together with some references into the supporting literature regarding aromatic carbon compounds in bio char to be found here:

http://www.css.cornell.edu/faculty/lehmann/publ/MitAdaptStratGlobChange%2011,%20403-427,%20Lehmann,%202006.pdf

I also have seen nothing like an EIS. (Before today or yesterday, I hadn’t realized that one ought to be generated.)

Falafulu — remember, click “reload” or “refresh” in your browser — I’m still noticing (Firefox, Windows) that some threads (not all of them, strangely, but some) open missing the last few responses when viewed. Reloading the page makes sure you’re seeing the latest responses, possibly including those you think aren’t being allowed.

Most everyone replying to you here is a reader like yourself, with no particular qualifications. Only the Contributors (listed in the right column) can make inline responses. Else it’s a conversation, not some institution you could be at odds with. You’re part of a crowd.

BioChar, lumps of carbon, whatever, it still doesnt work. In every decent analysis of sequestation Ive seen, for every ky of fuel burned it takes about another half kg of energy to get the carbon into a form we can grab hold of. Then there is the issue of transporting it to where its to be disposed of and restraining it in that place, which – I suspect – will take almost another half a kg. So in the end nature has her way, and it costs us as much to get carbon back down the hole as it does to get it out. ie Energy extracted by cracking the carbon-based fuel is similar to the energy required to get the carbon out of the emissions back into lumps or liquids we can handle and then to put it down the hole (often the same hole it came out of!). So it becomes a zero game.

We have to stop using GHG-impacting fuels at all. Its that simple. Just Stop It!

Nigel Williams(169) — Biopact states not so. Bioenergy is carbon-neutral. There is, potentially, an ample supply, over 4 times as much energy as mankind currently uses from all sources, according to them.

The fact of ample photosynthesis means that responsible folk can sequester the fossil carbon that others have burned. The exact costs are unknown to me, but biocoal is competitive with fossil coal in West and East Frisia, The Netherlands and Germany, where a group is building a pilot facility to produce 70,000 tonnes of biocoal per year.

If indeed it costs about the same amount to produce and sequester as fossil coal costs to mine and ship, then in the US the carbon tax for coal needs to be about $33 per ton. That covers the costs and also strongly encourages fossil coal consumers to convert to biocoal.

Most of this comes from

http://biopact.com

and is not original…

Ominous climate news for S.E. Australia…

Source: http://www.bom.gov.au/announcements/media_releases/climate/drought/20070903.shtml

Quote:

“Despite the rapid demise of the 2006 El Niño event, the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB) is still to see a sustained period of above average rainfall in the intervening period. This is the first time in the record dating from 1900 that an El Niño-drought in the MDB has not been followed by at least one three-month period with above normal rainfall (basin average) by the end of the following winter. Almost the entire basin shows well below average rainfall for periods starting in 2006.”

Re: 166 Michael: ” I agree there are many cases where a developing society can cause a reduction in GHG emissions. But the rule is: less poverty equals in increase in GHG’s, by far. Less poverty leading to a decrease in GHG’s is the exception, by far.”

Of course that’s been the rule so far, but then before now there has been no reason to even consider developing by any other route. Now there is a very pressing reason to do so. To argue that we are bound by how progress has been achieved in the past is to argue that there is no hope in finding a solution to anthropogenic climate change. Few here are willing to throw in the towel that easily.

Michael, a couple of points. I agree that in an environment like W. Africa, India, etc., development will correlate with rising energy consumption–but that does not HAVE TO correlate with rising GHG emissions. Indeed, with Western assistance, we can ensure it does not.

Second, having done science teacher training in W. Africa, your characterization is a bit simplistic. The type of education a country supports is critical to its development. China traditionally supported primary education, and this has led to a highly trained workforce. India emphasized higher education, and so has a very lopsided workforce. These choices have influenced the type of development the two countries have had. West African countries to date have tended to neglect both primary and higher education, leading to a severe brain drain. When I was in Africa, the governments were starting to try to improve science education–moving toward a more experiential model rather than “chalk and talk”. There is nothing in any of this that need necessarily lead to increased energy consumption.

Ray–

I’m not sure why you think western assistance can ensure that economic development in west africa does not result in vastly increased GHG emissions. I’m not trying to be critical, I’m just uninformed. What energy sources do we have in the west that can sustain development without GHG emissions?

Hi A.C, Most Africans and Indians live in villages. African and some Indian villages are still several years away from any hope of being on their country’s grid. The choices made for supplying energy and transportation infrastructure to these people will have consequences into the indefinite future. If we can supply their needs with renewable energy sources (mainly solar and wind), we will help lift them out of poverty while actually reducing their carbon footprint (their main energy sources now are charcoal, which results in deforestation). However, the choices these countries and people make will be driven by availability, technical issues (especialy energy storage) and cost. These are all issues we could help them with and thereby tilt the balance in favor of renewables.

Hank Roberts said…

Else it’s a conversation, not some institution you could be at odds with. You’re part of a crowd.

Yes, Hank, I know that I am part of the crowd, however the RealClimate admin has selectively published some of my comments (ones where I haven’t mentioned about climate feedback theory) and rejected most (ones where I have raised the feedback theory).

I had responded to Richard Ordway’s (#167) post directed at me, but the admin didn’t choose to publish it. Now, the admin has a right not to publish my comments, but if the admin selectively published some and rejected some, with no reason at all given. The rejected ones were not personal attack at all. They were about science of feedback theory and yet they were rejected for no reasons.

[[I’m not sure why you think western assistance can ensure that economic development in west africa does not result in vastly increased GHG emissions. I’m not trying to be critical, I’m just uninformed. What energy sources do we have in the west that can sustain development without GHG emissions?]]

Solar thermal power. Photovoltaics. Wind power. Geothermal power, both site-specific and Hot Dry Rock. Ocean thermal power. Wave and tidal power in specific locations. Biomass for liquid fuels.

To amplify on my earlier comments and those of Barton, the isolated nature of many populations in the developing world makes renewable energy sources competitive with fossil fuels economically because it is cheaper to bring in solar panels, windmills, etc. than to bring wires in from more inhabited areas. Brazil’s rural electrification project resolved the issue of bringing power to remote areas by installing diesel generators and bringing in fuel by boat on the rivers and then over short road trips. However, renewables are more attractive now.

A non-grid electric supply poses its own problems–chief among them reliability and energy storage. These need to be worked out if these approaches are to be viable. However, there is a possibility of making a huge dent in future ghg emissions if we act now. The advantage to the developing countries is considerable–cheap, clean power soon. The advantage to us is a more sustainable world in the future as we wean ourselves off of fossil fuels.

Michael wrote: “Before I say anything else, SecularAnimist, do you have any general objections to these generalities?”

Only the same objection that I already mentioned: you base your argument on various factual assertions — eg. “The worldwide average primary school is responsible for significant GHG’s” — without offering any evidence that these claims are, in fact, true. Where is your data on worldwide GHG emissions from primary schools on which you base that claim? Or is this something that you “just know” is true?

Plus the other objections that I previously mentioned:

1. You are begging the question of whether economic growth and the improvement of human well-being in the developing world necessarily requires increased GHG emissions from the developing world. You argue that it does, but all you offer in support of your argument is the assertion that it does.

2. You ignore the implications of regional climate change projections which strongly indicate that economic growth in the developing world will be undermined, thwarted and reversed by climate change, suggesting that mitigating climate change is not a hindrance to, but absolutely essential to, any hopes of improving human well-being in the developing world.

3. Regardless of whether increased energy production in developing countries necessarily leads to increased GHG emissions from developing countries, that is no argument against rich countries reducing their GHG emissions. To the contrary, it is an argument that people like you and me who are fortunate to live in the developed, industrialized world, should do everything we possibly can to reduce our GHG emissions, particularly since we — and our societies including both government and the private sector — have the technical and economic resources to do so, and since we are responsible for by far the vast majority of anthropogenic GHG emissions to date. Moreover, we should do everything we possibly can to assist the developing world to follow a climate-friendly and environmentally sustainable path to increased energy production and economic growth.

In summary, my objections are that your argument is not grounded in fact, and is unsound. I suggest you should rethink it.

Falafulu — I’m just a reader, but my suggestion is — put your ideas that aren’t obviously part of climate science on your own website (you can get one free lots of places including Google) and people will find them who are interested.

Carefully read the guidelines from the main page, those seem very important to what appears. You might do better once you’ve established your reputation and expertise on your own page. If what you want to teach isn’t recognized as needed by climatology, it’d be even more important to establish what it is coherently in one place on your own.

As western countries wean themselves from fossil fuels, fossil fuels will get cheaper and cheaper. It will be difficult to dissuade poorer countries from using them.

The world is going to need some new rules.

177

Yes, Hank, I know that I am part of the crowd, however the RealClimate admin has selectively published some of my comments (ones where I haven’t mentioned about climate feedback theory) and rejected most (ones where I have raised the feedback theory).

======================

An observation

That is an interesting accusation. I’ve been following this site for years now and I don’t recall anyone making this type of accusation. Historically, the moderators let pretty much everyone have their say so long as they play nice and follow the rules.

Of course, if they really wanted you to be censored, I would assume they could simply cut you off, particularly if they didn’t want to deal with the ongoing embarrassment of being accused of the type of censorship you are complaining about.

Yet here you are.

J. C. H., what you are ignoring is the fact that energy infrastructure is more important (and costly) than fuel. If developing nations choose a renewable-energy infrastructure, this will pay dividends into the indefinite future, as they will be unlikely to abandon this infrastructure regardless of how cheap fossil fuel becomes. In any case, I think we are in no danger of seeing fossil fuel prices fall any time soon. Our own infrastructure will probably keep us using oil for transport if nothing else and coal-fired power plants are unlikely to be shut down short of their useful lifetime. My goal is to try to meet the growth in energy demand with renewables and conservation and make whatever cuts we can as this becomes feasible.

My point is that for many applications non-ghg generating technologies are close to competitive, and small actions/gestures could tip the balance in their favor, with benefits to both us and developing countries.

My argument is: Reducing emissions will not make a bit of difference.

My argument is not: Reducing emissions is a bad idea, reducing emissions never helps, the guy with the air conditioned garages, heated driveways and three Escalades deserves a medal.

SecularAnimist: My arguments here are an exercise in logic, based on personal experience, my observances of human nature, and common sense. If you want statistics, studies or data, do your own legwork. If your arguments can’t stand on their own, there is no sense in engaging me.

I am not saying human development necessarily requires increased GHG emissions. On the contrary I offer my example of the teacher and student with nothing but a pad and paper and the blue sky. I am totally with you on the necessity argument; but my argument has to do with tendency.

Jim Eager: I don’t offer another solution, I am here looking for answers. I would like someone disqualify the statement: if you want to solve our problem, don’t look to reducing emissions, if you want to reduce emissions, don’t expect it to solve our problem. The consequences of what we have done to the planet are far too gradual to activate the human ‘Oh ****’ response. (Insert lame frog in boiling water or leading a horse to water analogy) Our children will see the brunt. To get the vector on the graph to take a sharp right turn, it would take a catastrophic event on the order of an asteroid or a 9/11.

A.C.(175) and subsequent posters — Again I encourage you to follow the articles on

http://biopact.com

to obtain some conception of how bioenergy is already beginning to transform the lives of the world’s poorest, and in a carbon-neutral (and sometimes carbon-negative) manner.

While it is true that this cylces more carbon dioxide through the atmosphere, it is being pulled out by photosynthesis at least as fast as it is being added.

Bioenergy is not just liquid fuels for transportation. It is bio-methane and bio-coal for heating, bio-char for soil conditioning, etc. A primary advantage is that the processes of converting biomass into bioenergy forms are all rather low-tech, although often with some recent improvements.

Hank Roberts said…

put your ideas that aren’t obviously part of climate science on your own website

Hank, I think that feedback control theory is pretty much part of climate science. See the following reference.

“Inferring instantaneous, multivariate and nonlinear sensitivities for the analysis of feedback processes in a dynamical system: Lorenz model case-study”

http://pubs.giss.nasa.gov/docs/2003/2003_Aires_Rossow.pdf

J.S.McIntyre said…

Historically, the moderators let pretty much everyone have their say so long as they play nice and follow the rules.

Yes, I do follow the rules. I am new here, but that is not the point. Gavin censored one of my post last week, and he explained why, so I learnt not to do that again.

Government Accountability Project (GAP)

Free Speech for Climate Scientists – Free Conference Call

Wednesday, September 12th, 6:00 – 7:00 PM.

Featuring Rick Piltz, Director of Climate Science Watch and federal climate science whistleblower,

& Tarek Maasarani, GAP staff Attorney and co-author of Atmosphere of Pressure and Redacting the Science of Climate Change.

To register for this call, email Richard Kim-Solloway at richards@whistleblower.org

To listen to our previous calls, visit http://www.whistleblower.org/template/page.cfm?page_id=188

Background: As the second category 5 hurricane in as many weeks devastates Central America – the first time two such severe storms have made landfall in one season since 1886 – attention has sharply returned to questions over the imminent threat posed by climate change.

But while scientific opinion has reached a strong consensus on the seriousness of the changes and the role of human emissions in causing them, scientists working for Agencies like NASA have reported having their views suppressed and altered by appointees with no scientific training and a brief to promote the policies of the Bush Administration.

In 2005, GAP helped Rick Piltz – then a senior staffer in the U.S Climate Change Science Program – blow the whistle on the White House’s improper editing and censorship of scientific reports on global warming intended for the public and Congress.

GAP helped Rick release two major reports to The New York Times that documented the actual hand-editing by Chief of Staff Philip Cooney – a lawyer and former climate team leader with the American Petroleum Institute – thereby launching a media frenzy that resulted in the resignation of the “former” lobbyist, who left to work for ExxonMobil.

With Piltz’ leadership GAP has launched Climate Science Watch, a GAP program that reaches out to scientists, helps them fight off censorship, and brings to light the continued politicization of environmental science. He is also featured in the award-winning documentary, Everything’s Cool.

GAP also represented Dr. James Hansen, one of the world’s top climate scientists, who blew the whistle on NASA’s attempts to silence him. Hansen’s disclosures led GAP Staff Attorney, Tarek Massarani, to conduct a year-long investigation that found objectionable and possibly illegal restrictions on the communication of scientific information to the media.

His findings, summarized in Redacting the Science of Climate Change, included examples of the delaying, monitoring, screening, and denying of interviews, as well as the delay, denial, and inappropriate editing of press releases.

GAP also released a joint Atmosphere of Pressure report with the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) that combined GAP’s investigative reporting and legal analysis with the results of a UCS survey of federal climate scientists. The reports received broad national attention and have already been presented in testimony at two congressional oversight hearings.

Re #185: [I would like someone disqualify the statement: if you want to solve our problem, don’t look to reducing emissions, if you want to reduce emissions, don’t expect it to solve our problem.]

I don’t think anyone could honestly refute that statement. However, you can look at the situation from another direction. Take the statement “By reducing emissions sufficiently, and using other remediation techniques, it’s possible to reduce atmospheric CO2 to levels that will at least mitigate some of the worst effects of AGW. No other effective/acceptable mitigation techniques are known”. That is (AFAIK, anyway) very probably a true statement, no?

Given that, you can either try to reduce emissions (and persuade others to do so), or do nothing. If you try, you may or may not succeed. If you don’t try, failure is guaranteed. Seems like a pretty easy choice to me.

re 185

You wrote: My argument is: Reducing emissions will not make a bit of difference.

My argument is not: Reducing emissions is a bad idea, reducing emissions never helps…

(I cut off the last part of your sentence as it is superfluous and, in relation to the first part, a bit of a non sequitur.)

Please explain how your claimed argument differs from the first two phrases of the argument you claim you are not making.

Re 185 – well, you do have something of a point about human behavior with regards to a slow moving threat. But aren’t at least some people smart enough and motivated enought to eat an at least somewhat healty diet and get some exercise (even some who have not already had a heart attack or stroke) – if people can do that, maybe they can be moved to respond to the threat of anthropogenic global warming. (It doesn’t have to be entirely voluntary – ultimately people have to volunteer to initiate policy agreements, but under those agreements, we would have commitments to each other, so that person A would feel more secure knowing that his/her efforts would not be for naught as person B carries on bussiness as usual (this commitment could be in the form of an emissions tax (with some agreement about the revenue allocation), which would leave individuals free to decide how much they want to spend on any given good or service, etc.).)

Reducing emissions, or at least reducing them from what they would otherwise grow to, will have an effect on climate.

Michael, you might be interested in a new book by Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine about how it is easier to introduce wholesale change after a disaster. Unfortunately, it tends to be the bad guys who benefit from disasters.

The link didn’t work for me, here it is:

http://www.cbc.ca/cp/entertainment/070902/e090206A.html

and a quote:

“Instead, she says, societies made vulnerable by natural disasters, war or other traumatic upheavals are increasingly being exploited by predatory capitalists who use the dislocation for their own profit-making ends.

The takeover of Iraq’s oil fields by western multinationals after the U.S.-led invasion, the sale of tsunami-wrecked beaches in Sri Lanka to luxury resort operators, the privatization of New Orleans public schools after the flood, and the establishment of a privatized homeland security apparatus after 9-11 are all examples, she says…”

Michael said (#185): “My arguments here are an exercise in logic, based on personal experience, my observances of human nature, and common sense. If you want statistics, studies or data, do your own legwork. If your arguments can’t stand on their own, there is no sense in engaging me.”

So is it unfair of me to translate this as “Well, I really haven’t done much research on this, but this is what I think and I’m a logical thinker, so it must be right?” Michael, could it be that maybe your experience could be incomplete. For instance, have you ever been to a developing country? Have you studied the cases of development in India, for instance, where the tech-heavy nature of the trend has produced large increases in the middle class with a smaller increase in energy consumption than, say, China, where development has been more industry intensive? Have you looked at issues of rural electrification in the face of increasing prices for not only fuel, but also copper, making a “wireless” energy solution much more appealing?

So, you may be right that humans are incapable of engineering growth while reducing ghg emissions, but if you are it is because the bulge of neurons on the top of our spinal chord has made us no more fit for survival than a colony of bacteria in a bottle. I would prefer to hope otherwise.

Re #186 – Biofuels

David Benson:

Biofuels are the worst idea people could think of as a real solution for our energy problems. The amount of land, water, fertilizers, pesticides, etc. required to produce large amounts of biofuels are staggering.

Brazil is already the 3rd or 4th largest emitter of GHGs thanks to the rampant deforestation of the Amazon to plant crops, mainly soy. Planting larger amounts of sugar cane for its much-touted and rapidly expanding ethanol biofuels industry will surely lead to even greater deforestation. Nothing could be more counter-productive since deforestation already accounts for about 20% of all GHG emission worldwide (mainly from Brazil and Indonesia). In fact, a recent report in Science (Renton Righelato et al., Science, Vol. 317, 2007, pg. 902) shows that conversion of tropical forest to cropland releases much more carbon per hectare than what is saved by ethanol production.

Do we want to accelerate deforestation in third world countries to plant biofuel crops? I’m already hearing rumors that back in my country (Colombia) there’s a huge push for expanding cultivation of sugar cane for ethanol and oil palms for biodiesel, all at the expense of native forests.

And do we want to start expanding our already heavily polluting, energy-intensive agriculture to produce biofuels? It is very likely that with current technology, and with the exception of sugar cane ethanol, we would consume more energy to produce a gallon of biofuel than the energy contained in that gallon. Moreover, converting the whole US corn crop into ethanol will be enough to replace only a small fraction of all the gasoline the US consumes, while the price of all foodstuffs (now mostly based on corn) will skyrocket.

We have already taken over ~40% of the worlds land surface for agriculture and cattle (Jonathan A. Foley et al., Science, Vol. 309. no. 5734, pp. 570 – 574, 2005) and a lot of that land is being rapidly degraded by unsustainable agricultural practices (deserts are growing at record speeds). Do we want to appropriate even more land to produce biofuels?

Photosynthesis is a pretty inefficient process in terms of the amount of chemical energy that is produced per unit of input solar energy, and to that you have to add all the other inefficiencies in the process of converting the plant material into a fuel. So the amount of land required to produce a certain amount of energy is enormous compared to what would be needed by photovoltaics (solar cells) or solar-thermal systems.

The current biofuels push is just a huge scam that only benefits the agri-business lobby.

Re #195

I forgot to add a link to a good article about this issue of biofuels:

http://feinstein.senate.gov/05speeches/ethanol-oped.htm

Re 185 Michael: “if you want to solve our problem, don’t look to reducing emissions, if you want to reduce emissions, don’t expect it to solve our problem.”

Sorry, I see no point in tilting at your catch 22 conundrum. I don’t know about where you live, but where I live climate change consistently tops the polls of public concern; lately there is a news segment or program addressing it on television almost every night of the week; individual people and municipal governments are embracing conservation and energy reduction strategies, technologies and appliance; local grass roots groups are forming to make bulk purchases of residential solar voltaic and hot water systems and install shared ground-source heat pumps; local business consortiums have developed two large wind farms (60+ and 100+ turbines) with at least two more in the planning stage; the municipal government has constructed and is expanding a deep-water cooling and heating system in the urban core; higher government has committed to a multi-billion dollar program to expand public transit and implemented substantial tax rebates for the purchase of hybrids, flex-fuel and more fuel efficient conventional cars and people are buying them. While some people are still busy wringing their hands or even still dragging their feet the rest of us are busy getting on with it.

Re 192 Holly Stick: “Michael, you might be interested in a new book by Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine about how it is easier to introduce wholesale change after a disaster.”

Hey Holly, good to see you here at RC. I just came back from Naomi’s talk and launch of the book at the UofT. Unfortunately she doesn’t mention climate change in it at all, which is unfortunate since it could potentially be the mother of all shock disasters. – Transplant

Re 179, Ray writes:

A non-grid electric supply poses its own problems–chief among them reliability and energy storage. These need to be worked out if these approaches are to be viable.

The grid is your friend. It provides the means by which the statistics get to work themselves out.

What utilities talk about “grid instability” what they are talking about is having to work harder — not the impossibility of having a stable grid. And the cost, based on a variety of studies I’ve referenced here in the past, is pennies per kilowatt-hour. Compared to rising fuel prices, that’s, uh, free in a few more years.

[[My argument is: Reducing emissions will not make a bit of difference.]]

Then your argument is wrong. Reducing emissions will make all the difference in the world. That is what the whole debate is about.