The sea level rise numbers published in the new IPCC report (the Fourth Assessment Report, AR4) have already caused considerable confusion. Many media articles and weblogs suggested there is good news on the sea level issue, with future sea level rise expected to be a lot less compared to the previous IPCC report (the Third Assessment Report, TAR). Some articles reported that IPCC had reduced its sea level projection from 88 cm to 59 cm (35 inches to 23 inches) , some even said it was reduced from 88 cm to 43 cm (17 inches), and there were several other versions as well (see “Broad Irony”). These statements are not correct and the new range up to 59 cm is not the full story. Here I will try to clarify what IPCC actually said and how these numbers were derived. (But if you want to skip the details, you can go straight to the critique or the bottom line).

What does IPCC say?

The Summary for Policy Makers (SPM) released last month provides the following table of sea level rise projections:

| Sea Level Rise (m at 2090-2099 relative to 1980-1999) |

|

| Case | Model-based range excluding future rapid dynamical changes in ice flow |

| B1 scenario | 0.18 – 0.38 |

| A1T scenario | 0.20 – 0.45 |

| B2 scenario | 0.20 – 0.43 |

| A1B scenario | 0.21 – 0.48 |

| A2 scenario | 0.23 – 0.51 |

| A1FI scenario | 0.26 – 0.59 |

It is this table on which the often-cited range of 18 to 59 cm is based. The accompanying text reads:

• Model-based projections of global average sea level rise at the end of the 21st century (2090-2099) are shown in Table SPM-3. For each scenario, the midpoint of the range in Table SPM-3 is within 10% of the TAR model average for 2090-2099. The ranges are narrower than in the TAR mainly because of improved information about some uncertainties in the projected contributions15. {10.6}.

Footnote 15: TAR projections were made for 2100, whereas projections in this Report are for 2090-2099. The TAR would have had similar ranges to those in Table SPM-3 if it had treated the uncertainties in the same way.

• Models used to date do not include uncertainties in climate-carbon cycle feedback nor do they include the full effects of changes in ice sheet flow, because a basis in published literature is lacking. The projections include a contribution due to increased ice flow from Greenland and Antarctica at the rates observed for 1993-2003, but these flow rates could increase or decrease in the future. For example, if this contribution were to grow linearly with global average temperature change, the upper ranges of sea level rise for SRES scenarios shown in Table SPM-3 would increase by 0.1 m to 0.2 m. Larger values cannot be excluded, but understanding of these effects is too limited to assess their likelihood or provide a best estimate or an upper bound for sea level rise. {10.6}

• If radiative forcing were to be stabilized in 2100 at A1B levels, thermal expansion alone would lead to 0.3 to 0.8 m of sea level rise by 2300 (relative to 1980–1999). Thermal expansion would continue for many centuries, due to the time required to transport heat into the deep ocean. {10.7}

• Contraction of the Greenland ice sheet is projected to continue to contribute to sea level rise after 2100. Current models suggest ice mass losses increase with temperature more rapidly than gains due to precipitation and that the surface mass balance becomes negative at a global average warming (relative to pre-industrial values) in excess of 1.9 to 4.6°C. If a negative surface mass balance were sustained for millennia, that would lead to virtually complete elimination of the Greenland ice sheet and a resulting contribution to sea level rise of about 7 m. The corresponding future temperatures in Greenland are comparable to those inferred for the last interglacial period 125,000 years ago, when paleoclimatic information suggests reductions of polar land ice extent and 4 to 6 m of sea level rise. {6.4, 10.7}

• Dynamical processes related to ice flow not included in current models but suggested by recent observations could increase the vulnerability of the ice sheets to warming, increasing future sea level rise. Understanding of these processes is limited and there is no consensus on their magnitude. {4.6, 10.7}

• Current global model studies project that the Antarctic ice sheet will remain too cold for widespread surface melting and is expected to gain in mass due to increased snowfall. However, net loss of ice mass could occur if dynamical ice discharge dominates the ice sheet mass balance. {10.7}

• Both past and future anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions will continue to contribute to warming and sea level rise for more than a millennium, due to the timescales required for removal of this gas from the atmosphere. {7.3, 10.3}

(The above quotes document everything the SPM says about future sea level rise. The numbers in wavy brackets refer to the chapters of the full report, to be released in May.)

What is included in these sea level numbers?

Let us have a look at how these numbers were derived. They are made up of four components: thermal expansion, glaciers and ice caps (those exclude the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets), ice sheet surface mass balance, and ice sheet dynamical imbalance.

1. Thermal expansion (warmer ocean water takes up more space) is computed from coupled climate models. These include ocean circulation models and can thus estimate where and how fast the surface warming penetrates into the ocean depths.

2. The contribution from glaciers and ice caps (not including Greenland and Antarctica), on the other hand, is computed from a simple empirical formula linking global mean temperature to mass loss (equivalent to a rate of sea level rise), based on observed data from 1963 to 2003. This takes into account that glaciers slowly disappear and therefore stop contributing – the total amount of glacier ice left is actually only enough to raise sea level by 15-37 cm.

3. The contribution from the two major ice sheets is split into two parts. What is called surface mass balance refers simply to snowfall minus surface ablation (ablation is melting plus sublimation). This is computed from an ice sheet surface mass balance model, with the snowfall amounts and temperatures derived from a high-resolution atmospheric circulation model. This is not the same as the coupled models used for the IPCC temperature projections, so results from this model are scaled to mimic different coupled models and different climate scenarios. (A fine point: this surface mass balance does include some “slow” changes in ice flow, but this is a minor contribution.)

4. Finally, there is another way how ice sheets can contribute to sea level rise: rather than melting at the surface, they can start to flow more rapidly. This is in fact increasingly observed around the edges of Greenland and Antarctica in recent years: outlet glaciers and ice streams that drain the ice sheets have greatly accelerated their flow. Numerous processes contribute to this, including the removal of buttressing ice shelves (i.e., ice tongues floating on water but in places anchored on islands or underwater rocks) or the lubrication of the ice sheet base by meltwater trickling down from the surface through cracks. These processes cannot yet be properly modelled, but observations suggest that they have contributed 0 – 0.7 mm/year to sea level rise during the period 1993-2003. The projections in the table given above assume that this contribution simply remains constant until the end of this century.

As an example, take the A1FI scenario – this is the warmest and therefore defines the upper limits of the sea level range. The “best” estimates for this scenario are 28 cm for thermal expansion, 12 cm for glaciers and -3 cm for the ice sheet mass balance – note the IPCC still assumes that Antarctica gains more mass in this manner than Greenland loses. Added to this is a term according to (4) simply based on the assumption that the accelerated ice flow observed 1993-2003 remains constant ever after, adding another 3 cm by the year 2095. In total, this adds up to 40 cm, with an ice sheet contribution of zero. (Another fine point: This is slightly less than the central estimate of 43 cm for the A1FI scenario that was reported in the media, taken from earlier drafts of the SPM, because those 43 cm was not the sum of the individual best estimates for the different contributing factors, but rather it was the mid-point of the uncertainty range, which is slightly higher as some uncertainties are skewed towards high values.)

How do the new numbers compare to the previous report?

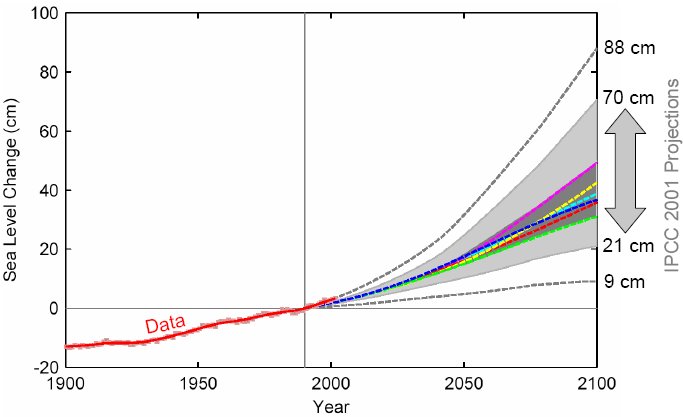

Sea level rise as observed (from Church and White 2006) shown in red up to the year 2001, together with the IPCC (2001) scenarios for 1990-2100. See second figure below for a zoom into the period of overlap.

The TAR showed sea level rise curves for a range of emission scenarios (shown in the Figure above together with the new observational record of Church and White 2006). The range was based on simulations with a simple model (the MAGICC model) tuned to mimic the behaviour of a range of different complex climate models (e.g. in terms of different climate sensitivities ranging from 1.7 to 4.2 ºC), combined with simple equations for the glacier and ice sheet mass balances (“degree-days scheme”). This model-based range is shown as the grey band (labelled “Several models all SRES envelope” in the original Figure 5 of the TAR SPM) and ranged from 21 to 70 cm, while the central estimate for each emission scenario is shown as a coloured dashed line. The largest central estimate of sea level rise is for the A1FI scenario (purple, 49 cm).

In addition, the dashed grey lines indicate additional uncertainty in ice sheet behaviour. These lines were labelled “All SRES envelope including land ice uncertainty” in the TAR SPM and extended the range up to 88 cm, adding 18 cm at the top end. One has to delve deeply into the appendix of Chapter 11 of the TAR to find out what these extra 18 cm entail: they include a “mass balance uncertainty” and an “ice dynamic uncertainty”, where the latter is simply assumed to be 10% of the total computed mass loss of the Greenland ice sheet. Note that such an ice dynamic uncertainty was only included for Greenland but not for Antarctica; instability of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, a scenario considered “very unlikely” in the TAR, was explicitly not included in the upper limit of 88 cm.

As we mentioned in our post on the release of the SPM, it is apples and oranges to say that IPCC reduced the upper sea level limit from 88 cm to 59 cm, as the former included “ice dynamic uncertainty” (albeit only for Greenland, as rapid ice flow changes in Antarctica were considered too unlikely to bother at the time), while the latter discusses this ice flow uncertainty separately in the text, stating it could add 10 cm, 20 cm or even more to the 59 cm in the table.

So is it better to compare the model-based range 21 – 70 cm from the TAR to the 18 – 59 cm from the AR4? Even that is apples and oranges. For one, TAR cites the rise up to the year 2100, the AR4 up to the period 2090-2099, thus missing the last 5 years (or 5.5 years, but let’s not get too pedantic) of sea level rise. For 2095, the TAR projection reduces from 70 cm to 65 cm (the central estimate for A1FI reduces from 49 cm to 46 cm). Also, the TAR range is a 95% confidence interval, the AR4 range a narrower 90% confidence interval. Giving the TAR numbers also as 90% ranges shaves another 3 cm off the top end.

Sounds complicated? There are some more technical differences… but I will spare you those. The Paris IPCC meeting actually discussed the request from some delegates to provide a direct comparison of the AR4 and TAR numbers, but declined to do this in detail for being too complicated. The result was the two statements:

The TAR would have had similar ranges to those in Table SPM-3 if it had treated the uncertainties in the same way.

and

For each scenario, the midpoint of the range in Table SPM-3 is within 10% of the TAR model average for 2090-2099.

(In fact delegates were told by the IPCC authors in Paris that with the new AR4 models, the central estimate for each scenario is slightly higher that with the old models, if numbers are reported in a comparable manner.)

The bottom line is thus that the methods have significantly improved (which is the reason behind all those methodological changes), but the expectation of how much sea level will rise in the coming century has not significantly changed. The biggest change is that ice sheet dynamics look more uncertain now than at the time of the TAR, which is why this uncertainty is not included any more in the cited range but discussed separately in the text.

Critique – Could these numbers underestimate future sea level rise?

There’s a number of issues worth discussing about these sea level numbers.

The first is the treatment of potential rapid changes in ice flow (item 4 on the list above). The AR4 notes that the ice sheets have been losing mass recently (the analysis period is 1993-2003). Greenland has contributed +0.14 to +0.28 mm/year of sea level rise over this period, while for Antarctica the uncertainty range is -0.14 to +0.55 mm/year. It is noted that the mass loss of Antarctica is mostly or entirely due to recent changes in ice flow. The question then is: how much will this process contribute to future sea level rise? The honest answer is: we don’t know. As the SPM states, by the year 2095 it could be 10 cm. Or 20 cm. Or more. Or less.

The IPCC included one guess into the “model-based range” provided in the table: it took half of the Greenland mass loss and the whole Antarctic mass loss for 1993-2003, and assumed this would remain constant ever after until 2100. This assumption in my view has no scientific basis, as the ice-flow is almost certainly highly variable in time. The report itself states that this ice loss is due to a recent acceleration of flow, and that in 2005 it was already higher, and that in future the numbers could be several times higher – or they could be lower. Adding such an ill-founded number into the “model-based” range degrades the much more reliable estimates for thermal expansion, mountain glaciers and mass balance. Even worse: to numbers with error estimates, it adds a number without proper error estimate (the observational uncertainty for 1993-2003 is included, but who would claim this is an error estimation for future ice flow changes?). And then it presents only the combined error margins – you will notice that no central estimate is provided in the above table. If I had presented this as an error calculation in a first-semester physics assignment, I doubt I would have gotten away with it. The German delegation in Paris (of which I was a member) therefore suggested taking this ice-flow estimate out of the tabulated range. The numbers would have become slightly lower, but this approach would not have mixed up very different levels of uncertainty, and it would have been clear what is included in the table and what is not (namely ice flow changes), rather than attempting to partially include ice flow changes. The ice flow changes could have been discussed in the text – stating there that at the 1993-2003 rate, this term would contribute 3 cm by 2095, but it is bound to change and could turn out to be 10 cm or 20 cm or more. However, we found no support for this proposal, which would not have changed the science in any way but improved the clarity of presentation.

As it is now, because of the complex and opaque way of combining the errors, even I could not tell you by how much the upper limit of 59 cm would be reduced if the questionable ice flow estimate was taken out, and one of the reasons provided by the IPCC authors for not adopting our proposal was that the numbers could not be calculated quickly.

A second problem with the above range is that the models used to derive this projection significantly underestimate past sea level rise. We tried in vain to get this mentioned in the SPM, so you have to go to the main report to find this information. The AR4 states that for the period 1961-2003, the models on average give a rise of 1.2 mm/year, while the data show 1.8 mm/year, i.e. a 50% faster rise. This is despite using observed ice sheet mass loss (0.19 mm/year) in the “modelled” number in this comparison, otherwise the discrepancy would be even larger – the ice sheet models predict that the ice sheets gain mass due to global warming. The comparison looks somewhat better for the period 1993-2003, where the “models” give a rise of 2.6 mm/year while the data give 3.1 mm/year. But again the “models” estimate includes an observed ice sheet mass loss term of 0.41 mm/year whereas ice sheet models give a mass gain of 0.1 mm/year for this period; considering this, observed rise is again 50% faster than the best model estimate for this period. This underestimation carries over from the TAR models (see Rahmstorf et al. 2007 and the Figure below) – this is not surprising, since the new models give essentially the same results as the old models, as discussed above.

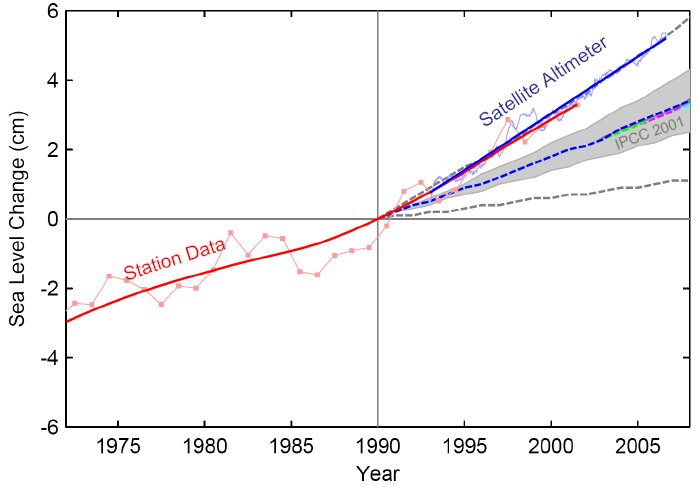

Comparison of the 2001 IPCC sea-level scenarios (starting in 1990) and observed data: the Church and White (2006) data based primarily on tide gauges (annual, red) and the satellite altimeter data (updated from Cazenave and Nerem 2004, 3-month data spacing, blue, up to mid-2006) are shown with their trend lines. Note that the observed sea level rise tends to follow the uppermost dashed line of the IPCC scenarios, namely the one “including land ice uncertainty”, see first Figure.

We therefore see that sea level appears to be rising about 50% faster than models suggest – consistently for the 1961-2003 and the 1993-2003 periods, and for the TAR models and the AR4 models. This could have a number of different reasons, and the discrepancy could be considered not significant given the error ranges of observations and models. It is no proof that models underestimate future sea level rise. But it is at least a plausible possibility that the models may underestimate future rise.

A third issue worth mentioning is that of carbon cycle feedback. The temperature projections provided in table SPM-3 of the Summary for Policy Makers range from 1.1 to 6.4 ºC warming and include carbon cycle feedback. The sea level range, however, is based on scenarios that exclude this feedback and thus only range up to 4.5 5.2 ºC. This could easily be misunderstood, as in table SPM-3 the temperature ranges including carbon cycle feedback are shown right next to the sea level ranges, but the latter actually apply to a smaller temperature range. As a rough estimate, I suggest that for a 6.4 ºC warming scenario, of the order of 20 15 cm would have to be added to the 59 cm defining the upper end of the sea level range.

A final point is the regional aspects. Planners of coastal defences need to be aware that sea level rise will not be the same everywhere. The AR4 shows a map of regional sea level changes, which shows that e.g. European coasts can expect a rise by 5-15 cm more than the global mean rise – that is a model average, not including an uncertainty range. The pattern in this map is remarkably similar to that expected from a slowdown in thermohaline circulation (see Levermann et al. 2005) so probably it is dominated by this effect. In addition, some land areas are rising and some are subsiding in response to the end of the last Ice Age or due to local anthropogenic processes (e.g. groundwater withdrawal), which local planners need to account for.

The main conclusion of this analysis is that sea level uncertainty is not smaller now than it was at the time of the TAR, and that quoting the 18-59 cm range of sea level rise, as many media articles have done, is not telling the full story. 59 cm is unfortunately not the “worst case”. It does not include the full ice sheet uncertainty, which could add 20 cm or even more. It does not cover the full “likely” temperature range given in the AR4 (up to 6.4 ºC) – correcting for that could again roughly add 20 15 cm. It does not account for the fact that past sea level rise is underestimated by the models for reasons that are unclear. Considering these issues, a sea level rise exceeding one metre can in my view by no means ruled out. In a completely different analysis, based only on a simple correlation of observed sea level rise and temperature, I came to a similar conclusion. As stated in that paper, my point here is not that I predict that sea level rise will be higher than IPCC suggests, or that the IPCC estimates for sea level are wrong in any way. My point is that in terms of a risk assessment, the uncertainty range that one needs to consider is in my view substantially larger than 18-59 cm.

A final thought: this discussion has all been about sea level rise until the year 2095. Sea level rise does not end there, as the quotes from the SPM at the beginning of this article show. Over several centuries, without serious mitigation efforts we may expect several meters of sea level rise. The Advisory Council on Global Change of the German government (disclosure: I’m a member of this body) in its recent special report on the oceans has proposed to limit long-term sea level rise to a maximum of one meter, as a guard-rail to guide climate policy. But that’s another story.

Update: I was just informed by one of the IPCC authors that the temperature scenarios without carbon cycle feedback range up to 5.2 ºC, not 4.5 ºC as I had assumed. This number is not found in the IPCC report; I had tried to interpret it from a graph, but not accurately enough. My apologies! The numbers in the text above that had to be corrected are marked by strikethrough font. -stefan

O aumento do nível do mar publicado no novo relatório do IPCC (o Quarto Relatório de Avaliação, AR4) já tem causado confusão considerável. Muitos artigos da mídia sugerem que há boas notícias sobre a questão do nível do mar, com previsões muito menores de aumento do nível do mar comparadas às previsões do relatório anterior do IPCC (o Terceiro Relatório de Avaliação, TAR). Alguns artigos reportam que o IPCC reduziu a projeção para o aumento do nível do mar de 88 para 59 cm, enquanto outros dizem que tal projeção teria sido reduzida de 88 para 43 cm, e existem muitas outras versões também (veja “Ampla Ironia”). Tais declarações são incorretas dado que o novo valor de até 59 cm não representa sequer toda a estória. Aqui tentarei clarear o que o IPCC de fato quer dizer e como esses números são derivados. (Mas caso prefira pular os detalhes, vá direto para a crítica ou a última linha).

O que o IPCC diz?

O Sumário para Tomadores de Decisão (SPM) lançado no ultimo mês fornece a seguinte tabela de projeções para o aumento do nível do mar:

| Aumento do Nível do Mar (em metros para 2090-2099 relativo a 1980-1999) |

|

| Caso | Intervalo baseado em modelo excetuando-se rápidas mudanças futuras no fluxo de gelo |

| Cenário B1 | 0.18 – 0.38 |

| Cenário A1T | 0.20 – 0.45 |

| Cenário B2 | 0.20 – 0.43 |

| Cenário A1B | 0.21 – 0.48 |

| Cenário A2 | 0.23 – 0.51 |

| Cenário A1FI | 0.26 – 0.59 |

É desta tabela que sai o usualmente citado intervalo de 18 a 59 cm. O texto que acompanha a tabela diz:

•

Projeções baseadas em modelos da elevação do nível do mar no final do século XXI (2090-2099) são mostradas na Tabela SPM-3. Para cada cenário, o ponto médio do intervalo na Tabela SPM-3 situa-se dentro de 10% da média do modelo do TAR para 2090-2099. Os intervalos são mais estreitos que no TAR principalmente devido às melhorias na informação sobre algumas incertezas nas contribuições projetadas15. {10.6}.nota de rodapé

15: As pojeções no TAR foram feitas para 2100, enquanto que as projeções desse relatório são para 2090-2099. O TAR deveria apresentar intervalos similares aos da Tabela SPM-3 se as incertezas tivessem sido tratadas da mesma maneira.• Os modelos atuais não incluem incertezas do feedback climático do ciclo do carbono e tão pouco incluem efeitos completos das mudanças dos fluxos das placas de gelo, dado que ainda faltam fundamentos publicados na literatura. As projeções incluem uma contribuição devido ao aumento do fluxo de gelo da Groenlândia e Antártica em taxas observadas para 1993-2003, mas tais taxas de fluxo poderiam aumentar ou diminuir no futuro. Por exemplo, se essa contribuição crescer linearmente com a mudança da temperatura média global, os intervalos superiores da elevação do nível do mar nos cenários SRES (Relatório Especial dos Cenários de Emissão do IPCC) mostrados na Tabela SPM-3 deveriam aumentar em 0.1 m a 0.2 m. Valores maiores não podem ser excluídos, mas o conhecimento desses efeitos é muito limitado para avaliar suas probabilidades ou fornecer uma melhor estimativa ou um limite superior para o aumento do nível do mar. {10.6}

• Se a forçante radiativa fosse estabilizar em 2100 em níveis estimados no cenário A1B, a expansão térmica somente levaria a um aumento do nível do mar de 0.3 a 0.8 m em 2300 (relativo a 1980–1999). A expansão térmica continuaria por muitos séculos, devido ao tempo requerido para transportar calor para o oceano profundo. {10.7}

• A contração da camada de gelo da Groenlândia é projetada a continuar contribuindo para o aumento do nível o mar após 2100. Os modelos atuais sugerem que um aumento da perda de massa de gelo com a temperatura seria mais rápido do que um ganho de massa de gelo com a precipitação, e que o balanço de massa da superfície tornaria-se negativo sob um aquecimento global médio (relativo aos valores pré-industriais) excedendo 1.9 a 4.6°C. Se um balanço negativo de massa da superfície fosse sutentado por milênios, isso levaria a uma eliminação virtualmente completa da cobertura de gelo da Groenlândia e uma contribuição resultante do aumento do nível do mar ao redor de 7 m. As temperaturas futuras correspondentes na Groenlândia são comparáveis àquelas inferidas para o último período interglacial há 125 mil anos atrás, quando as informações paleoclimáticas sugerem uma redução da extensão de gelo polar e um aumento do nível do mar de 4 a 6 m. {6.4, 10.7}

• Processos dinâmicos relacionados o fluxo de gelo não incluídos nos modelos atuais mas sugeridos por recentes observações poderia aumentar a vulnerabilidade das placas de gelo ao aquecimento, aumentando a elevação do nível do mar no futuro. A compreensão desses processos é limitada e não há consenso sobre sua magnitude. {4.6, 10.7}

• Estudos atuais de modelos globais projetam que a camada de gelo Antártica pode permanecer muito fria para um amplo derretimento superficial e espera-se um ganho de massa devido a um aumento de queda de neve. Contudo, uma perda líquida de gelo poderia ocorrer se uma descarga dinâmica de gelo dominar o balanço de massa da camada de gelo. {10.7}

• Ambas as emissões antropogênicas passadas e futuras de dióxido de carbono deverão continuar a contribuir no aquecimento e na elevação do nível do mar por mais de um milênio, por conta da escala de tempo requerida para a remoção desse gás da atmosfera. {7.3, 10.3}

(Os itens acima documentam tudo que o SPM diz sobre o futuro da elevação do nível do mar. Os números entre chaves refem-se aos capítulos do relatório completo a ser divulgado em maio.)

O que está incluso nesses números de nível do mar?

Vamos olhar como esses números são derivados. Eles são constituídos de quatro componentes: expansão térmica, geleiras e camadas de gelo (excetuando-se as capas de gelo da Groenlândia e Antártica), balanço de massa de placas de gelo superficiais, e o desbalanço dinâmico das placas de gelo.

1. Expansão térmica (água oceânica mais quente ocupa maior espaço) é computada de modelos climáticos acoplados. Esses incluem modelos de circulação oceânica e podem assim estimar onde e quão rápido o aquecimento superficial penetra nos oceanos profundos.

2. A contribuição de geleiras e camadas de gelo (não incluindo Groenlândia e Antártica), por sua vez, é computada de uma simples formulação empírica que liga a temperatura média global à perda de massa (equivalente a uma taxa de elevação do nível do mar), baseada em dados observados entre 1963 e 2003. Tal formulação considera que as geleiras desaparecem vagarosamente e conseqüentemente param de contribuir – a quantidade total de geleiras remanecente seria suficiente para elevar o nível do mar em 15-37 cm.

3. A contribuição das duas maiores coberturas de gelo é dividida em duas partes. O que é chamado de balanço de massa superficial se refere simplesmente a queda de neve menos a ablação de gelo superficial (que é o derretimento somado à sublimação). Este é computado por um modelo de balanço de massa de placa de gelo superficial, com as quantidades de queda de neve e temperaturas derivados de um modelo de alta resolução da circulação atmosférica. Este cálculo não é o mesmo dos modelos acoplados usados nas projeções de temperatura do IPCC, de modo que os resultados desse modelo são ajustados para mimetizar diferentes modelos acoplados e diferentes cenários climáticos. (Um importante detalhe: esse balanço de massa superficial inclui algumas mudanças “morosas” no fluxo de gelo, mas essa é uma pequena contribuição.)

4. Finalmente, existe um outro modo pelo qual as placas de gelo podem contribuir para a elevação do nível do mar: ao invés de derreterem na superfície, podem começar a fluir mais rapidamente. Isso vem sendo observado com freqüência ao redor das bordas da Groenlândia e Antártica em anos recentes: saídas de geleiras e rios de gelo que drenam as placas de gelo têm aumentado suas vazões. Numerosos processos contribuem para isso, incluindo a remoção de conchas de gelo (i.e., gelos que flutuam sobre a água ancoradas em ilhas ou rochas submersas) ou a erosão da base da placa de gelo por água líquida fluindo pela superfície através de falhas no gelo. Tais processos não podem ainda ser adequadamente modelados, mas as observações sugerem que eles têm contribuído com 0 – 0.7 mm/ano para a elevação do nível do mar no período 1993-2003. As projeções na dada tabela assumem que tal contribuição simplesmente se mantém constante até o fim deste século.

Por exemplo, tome o cenário A1FI – este é o mais quente e por isso define os limites superiores do intervalo do nível do mar. A “melhor” estimativa desse cenário é 28 cm para a expansão térmica, 12 cm para as geleiras e -3 cm para o balanço de massa das placas de gelo – note que o IPCC ainda assume que a Antártica ganha mais massa através desse modo do que a Groenlândia perde. Adicionado a isso há um termo de acordo com (4) simplesmente baseado na premissa de que o acelerado fluxo de gelo observado em 1993-2003 se mantém sempre constante, adicionando outros 3 cm em 2095. No total, isso totaliza até 40 cm, com uma contribuição nula das placas de gelo. (Outro ponto importante: Isso representa um pouco menos do que a estimativa central de 43 cm para o cenário A1FI que foi divulgado na mídia, tirado dos primeiros rascunhos do SPM, pois estes 43 cm não eram a soma das melhores estimativas individuais para os diferentes fatores contribuintes, mas, ao contrário, era um ponto médio do intervalo das incertezas, o qual é um pouco maior quando algumas incertezas são tomadas com valores mais altos.)

Como esses números se comparam com o relatório anterior?

Elevação do nível do mar como verificado em Church e White 2006 mostrado em vermelho até o ano de 2001, junto com os cenários do IPCC (2001) para 1990-2100. Veja a segunda figura abaixo para um zoom no período de sobreposição.

O TAR mostrou curvas de elevação de nível do mar para uma gama de cenários de emissão (mostrada na Figura acima junto com novos dados obervacionais de Church e White 2006). Essa gama foi baseada em simulações com um modelo simples (o modelo MAGICC) ajustado para mimetizar o comportamento de uma gama de diferentes modelos climáticos complexos (por exemplo em termos de diferentes sensibilidades climáticas variando de 1.7 a 4.2 ºC), combinado com equações simples para um glacial e balanços de massa de placa de gelo (“esquema graus-dias”). Este intervalo baseado em modelo é mostrado como uma banda verde (legendada como “Several models all SRES envelope” na Figura 5 original do TAR SPM) e variou de 21 a 70 cm, enquanto que a estimativa central para cada cenário de emissão é mostrada como uma linha tracejada colorida. A maior estimativa central da elevação do nível do mar foi para o cenário A1FI (cor púrpura, 49 cm).

Ainda mais, as curvas tracejadas em cinza indicam incertezas adicionais no comportamento das placas de gelo. Tais linhas foram legendadas como “All SRES envelope including land ice uncertainty” no TAR SPM e ampliou o intervalo até 88 cm, adicionando 18 cm no limite superior. É preciso procurar minuciosamente no apêndice do Capítulo 11 do TAR para encontrar o que esses 18 cm extras representam: eles incluem uma “incerteza no balanço de massa” e uma “incerteza de dinâmica de gelo”, onde o último é meramente assumido como 10% da perda de massa total computada para a placa de gelo da Groenlândia. Note que tal incerteza na dinâmica de gelo foi somente incluída para a Groenlândia mas não para a Antártica; instabilidade da Placa de Gelo Oeste da Antártica, um cenário considerado “muito improvável” no TAR, foi explicitamente não incluído no limite superior de 88 cm.

Como mencionamos em nossa postagem sobre a divulgação do SPM, seria comparar maçãs e laranjas ao dizer que o IPCC reduziu o limite superior do nível do mar de 88 cm para 59 cm, a medida em que o primeiro incluiu “a incerteza da dinâmica do gelo” (muito embora somente para a Groenlândia, pois mudanças rápidas do fluxo de gelo na Antártica foram consideradas muito improváveis para preocupar naquele tempo), enquanto que o segundo discute essa incerteza do fluxo de gelo separadamente no texo, declarando que isso poderia adicionar 10 cm, 20 cm ou ainda mais aos 59 cm da tabela.

Assim seria melhor comparar o intervalo baseado em modelo de 21 – 70 cm do TAR com o 18 – 59 cm do AR4? Mesmo isso seria comparar maçãs com laranjas. Para um, o TAR cita a elevação até o ano 2100, o AR4 até o período 2090-2099, assim faltam os últimos cinco anos (ou 5.5 anos, mas não sejamos pedantes) da elevação do nível do mar. Para 2095, a projeção do TAR reduz de 70 cm para 65 cm (a estimativa central para o cenário A1FI reduz de 49 cm para 46 cm). Também, o intervalo do TAR é um intervalo de 95% de confiança, já o intervalo AR4 é mais estreito para um intervalo de confiança de 90%. Dados os números do TAR também como intervalos de 90% remove outros 3 cm do limite superior final.

Parece complicado? Existem outras diferenças mais técnicas… mas irei poupar-lhes disso. A reunião de Paris do IPCC já discutiu o pedido de alguns delegados de fornecer uma comparação direta dos números do AR4 e do TAR, mas desistiram de fazer isso detalhadamente por ser muito complicado. O resultado foi duas declarações:

O TAR deveria ter intervalos similares aos da Tabela SPM-3 se ele tivesse tratado as incertezas da mesma maneira.

e

Para cada cenário, o ponto médio do intervalo na Tabela SPM-3 está dentro de 10% da média do modelo TAR para 2090-2099.

(Na verdade, foi dito aos delegados pelos autores do IPCC em Paris que com os novos modelos AR4, as estimativas centrais de cada cenário seriam um pouco maiores que aquelas dos velhos modelos, se os números são reportados de forma comparável.)

A última linha mostra então que os métodos têm sido significativamente melhorados (razão por detrás de todos essas mudanças metodológicas), mas a expectativa de quanto o nível do mar irá subir no século que virá não mudou muito. A maior mudança é que a dinâmica das placas de gelo parecem mais incertas agora que no tempo do TAR, que é a razão para que esta incerteza não seja mais inclusa nos intervalos citados, mas sim discutida separadamente no texto.

Crítica – Poderiam esses números subestimar a futura elevação do nível do mar?

Existem várias discussões importantes sobre os números do nível do mar.

O primeiro é o tratamento das mudanças rápidas potenciais no fluxo de gelo (item 4 da lista acima). O AR4 aponta que as placas de gelo têm recentemente perdido massa (o período de análise é 1993-2003). A Groenlândia tem contribuído com +0.14 a +0.28 mm/ano para a elevação do nível do mar sobre esse período, enquanto que para a Antártica a incerteza varia de -0.14 a +0.55 mm/ano. É observado que a perda de massa da Antártica é predominante ou inteiramente devido às recentes mudanças do fluxo de gelo. A questão então é: Quanto esse processo irá contribuir para o futuro da elevação do nível do mar? A resposta honesta é: nós não sabemos. Como o SPM declara, pelo ano 2095 poderia ser 10 cm. Ou 20 cm. Ou mais. Ou menos.

O IPCC incluiu uma suposição no ‘intervalo baseado em modelo’ dado na tabela: tal suposição toma metade da perda de massa da Groenlândia e toda a perda de massa Antártica para 1993-2003, e assume que as perdas se manteriam sempre constantes até 2100. Essa permissa na minha visão não tem embasamento científico, pois o fluxo de gelo é quase que certamente muito variável no tempo. O relatório por si só declara que tal perda de gelo seja devida a uma aceleração recente do fluxo, e que em 2005 já era bastante alta, e no futuro os números poderiam ser várias vezes maior – ou poderiam ser menores. Incluindo um número fundamentalmente deficiente no intervalo ‘baseado em modelo’ degrada estimativas muito mais confiáveis para a expansão térmica, geleiras de montanhas e balanço de massa. Ainda pior: para os números com estimativas de erro, é adicionado um número sem uma estimativa apropriada de erro (a incerteza observada para 1993-2003 é incluída, mas quem asseguraria que esta seja válida para futuras mudanças no fluxo de gelo?). E então são apresentadas somente as margens de erro combinadas – você pode notar que nenhuma estimativa central é fornecida na tabela acima. Se eu tivesse apresentado isso como um erro de cálculo numa lição de casa no primeiro semestre de física, duvido que eu conseguiria escapar disso. A delegação alemã em Paris (da qual sou membro) então sugeriu tirar a estimativa do fluxo de gelo do intervalo tabulado. Os números se tornariam um pouco menores, mas esta abordagem não mesclaria níveis muito diferentes de incerteza, e ficaria claro o que estaria incluso na tabela e o que não estaria (as mudanças de fluxo de gelo), ao invés de tentar incluir parcialmente mudanças nos fluxos de gelo. Tais mudanças teriam sido discutidas no texto – dizendo que nas taxas de 1993-2003, tal termo poderia contribuir com 3 cm em 2095, mas esse valor poderia mudar para 10 cm ou 20 cm ou mais. Todavia, não encotramos nenhum suporte para esta proposta, a qual não teria mudado a Ciència de maneira alguma, mas melhorado a claridade da apresentação.

Como está agora, devido à forma complexa e obscura da combinação dos erros, até mesmo eu não poderia dizer por quanto o limite superior de 59 cm seria reduzido se a questionável estimativa fosse removida, e uma das razões para que os autores do IPCC não adotassem nossa proposta foi a de que os números não poderiam ser calculados rapidamente.

Um segundo problema com o intervalo acima é que os modelos usados para derivar as projeções subestimam significativamente a elevação do nível do mar em tempos pretéritos. Tentamos em vão fazer isso ser mencionado no SPM, de modo que você teria que ir ao relatório principal para encontrar essa informação. O AR4 declara que para o período 1961-2003, os modelos sobre as médias fornece uma elevação de 1.2 mm/ano, enquanto que os dados mostram 1.8 mm/ano, i.e. um crescimento 50% mais rápido. E isto sem considerar a taxa de perda de placa de gelo (0.19 mm/ano) nos números ‘modelados’ nesta comparação. Se assim fosse, a discrepância seria ainda maior – os modelos de placa de gelo prevèm que as placas de gelo ganhariam massa em função do aquecimento global. A comparação parece um pouco melhor no período de 1993-2003, para o qual os modelos fornecem uma elevação de 2.6 mm/ano enquanto os dados fornecem 3.1 mm/ano. Mas de novo as estimativas de ‘modelos’ incluem uma observada perda de massa de gelo de 0.41 mm/ano enquanto os modelos de placas de gelo fornecem um ganho de massa de 0.1 mm/ano para esse período; considerando isso, a elevação observada é de novo 50% mais rápida do que as melhores estimativas de modelos para esse período. Esta subestimativa persiste dos modelos do TAR (veja Rahmstorf et al. 2007 e Figura abaixo) – isso não é uma surpresa, desde que os novos modelos dão essencialmente os mesmos resultados dos modelos antigos, como discutido acima.

Comparação dos cenários do nível do mar do IPCC 2001 (com início em 1990) e dados observados: os dados de Church e White (2006) baseiam-se primariamente em estações de medição de maré (anual em vermelho) e dados de satélite altímetro (atualizado de Cazenave e Nerem 2004, dados espaçados de 3 meses, em azul, até meados de 2006) são mostrados com suas linhas de tendência. Note que a tendência de elevação do nível do mar segue a linha tracejada mais superior dos cenários do IPCC, exatamente aquela nomeada “incluindo a incerteza de gelo terrestre”, veja a primeira figura.

Nós então vemos que o nível do mar parece estar subindo cerca de 50% mais rápido que os modelos sugerem – consistentemente para os períodos de 1961-2003 e 1993-2003, e para os modelos TAR e AR4. Isso pode ter diversas razões, e a discrepância poderia ser considerada insignificante dados os intervalos de erros das obervações e modelos. Não há provas de que os modelos subestimam a elevação o nível do mar. Mas há no mínimo uma possibilidade plausível de que os modelos possam subestimar a elevação futura.

Uma terceira questão de importância diz respeito ao feedback do ciclo do carbono. As projeções de temperatura fornecidas na tabela SPM-3 do Sumário para Tomadores de Decisão variam de 1.1 a 6.4 ºC de aquecimento e inclui o feedback do ciclo do carbono. A variação do nível do mar, contudo, é baseada em cenários que excluem esse feedback e assim variam somente até 4.5 5.2 ºC. Isso poderia facilmente ser mal interpretado, pois na tabela SPM-3 os intervalos de temperatura que incluem o feedback do ciclo do carbono são mostrados ao lado dos intervalos do nível do mar, mas esses últimos na verdade aplicam-se a um menor intervalo de temperatura. Como uma estimativa grosseira, sugiro que para um cenário de aquecimento de 6.4 ºC, da ordem de 20 15 cm deveria ser adicionado aos 59 cm para definir o limite superior do intervalo de elevação do nível do mar.

Um ponto final seria os aspectos regionais. Gerentes de planejamento de zonas costeiras precisam ter conciência que a elevação do nível do mar não será a mesma em todos os lugares. O AR4 mostra um mapa de mudanças regionais do nível do mar, o qual mostra que por exemplo a costa européia pode esperar uma elevação de 5-15 cm a mais que a média global de elevação – isso é uma média de modelo, não incluindo a incerteza do intervalo. O padrão nesse mapa é marcadamente similar ao que seria esperado de uma desaceleração da na circulação termohalina (veja Levermann et al. 2005) de modo que provavelmente a elevação seja dominada por esse efeito. Além disso, algumas áreas terrestres estão surgindo e outras desaparecendo em resposta ao final da última era glacial ou devido à processos antropogênicos locais (como o uso de águas subterrâneas), os quais os gerentes e tomadores de decisão devem também considerar.

A principal conclusão dessa análise é que a incerteza do nível do mar não é menor agora que na época do TAR, e citar o intervalo de 18-59 cm para a elevação do nível do mar, como muitos artigos da mídia têm feito, não representa toda a estória. 59 cm não é infortunadamente o “pior caso”. Ele não inclui toda a incerteza das placas de gelo, a qual deveria adicionar 20 cm ou mais. Ele não cobre totalmente o ‘provável’ intervalo de temperatura dado no AR4 (até 6.4 ºC) – correções nesse sentido poderiam adicionar novamente cerca de 20 15 cm. Ele não considera o fato de que a elevação passada do nível do mar seja subestimada pelos modelos por razões que são pouco claras. Considerando essas questões, uma elevação do nível do mar que exceda um metro pode, no meu ponto de vista, de modo algum ser descartada. Numa análise muito diferente, baseada somente numa simples correlação da elevação do nível do mar e temperatura, eu cheguei a uma conclusão similar. Como citado nesse paper, meu ponto aqui não é que eu tenha previsto que o nível do mar será maior que o IPCC sugere, ou que as estimativas do IPCC para a elevação do nível do mar não estejam corretas. Meu ponto é que em termos de análise de risco, o intervalo de incerteza que alguém precisa considerar é na minha visão substancialmente maior que os 18-59 cm.

Um pensamento final: esta discussão tem sido sobre a elevação do nível do mar até o ano de 2095. E tal elevação não termina nesse ano, como mostra a citação do SPM no início desse artigo. Ao longo de muitos séculos, sem esforços sérios de mitigação podemos esperar muitos metros de elevação dos oceanos. O Conselho Consultivo em Mudança Global do governo alemão (elucidando: sou membro desse conselho) em seu recente relatório especial sobre oceanos tem proposto limitar a elevação do nível do mar a um máximo de um metro, como sendo uma meta a guiar a política climática. Mas isso é uma outra estória.

Atualização: Fui recém informado por um dos autores do IPCC que os cenários de intervalo de temperatura sem o feedback do ciclo do carbono varia até to 5.2 ºC, e não 4.5 ºC como pensava. Este número não é encontrado no relatório do IPCC; tentei interpretá-lo de um gráfico, mas não exato o suficiente. Minhas desculpas! Os números no texto acima devem ser corrigidos e estão marcados. -stefan

traduzido por Ivan B. T. Lima e Fernando M. Ramos

i posted a post on “gardening by the globe”, it recieved only 4 comments but was viewed by over 50 people and i got a email from one of the big shots on there who said my post would be deleted,here is what she wrote to me

Community Stats: 52964 forum posts, 1449 entries in 85 blogs have been added by 1464 members.

from the forum on gardenstew….

Home | Forums | Blogs | Calendar | Plants | | 14 new posts | 1 new blog entries

Inbox :: Message

From: toni

To: katsback

Posted: Sat Apr 07, 2007 2:05 am

Subject: The Global warming topic

Kat,

This topic is becoming too volatile and political so for the sake of the entire forum it will have to be deleted.

If you wish to argue about whether global warming is coming immediately please find a forum where that topic is allowed.

In a discussion, each persons opinion has just as much importance as anyone elses whether they agree with you or not.

Toni

co-moderator

i feel it shouldnt have been deleted, i just wish i could have sent you the post,it was deleted before i had a chance to save it!

the world has no chance of ever being saved if people like that are in charge!!!

Kat, unfortunately, the forum is geared to a particular group and the moderators have to exercise their judgement as to whether a particular subject is so controversial that it threatens to sew animosity. I do think that it would be appropriate to ask for guidance–is the entire subject of climate change off limits (an unreasonable, but probably legal position) or are there tight limits on tone, etc. that should be taken.

You are right, climate change is a crucial subject and should be of concern to any gardener that thinks about invasives, pests, etc.

RE #250 (&249), I hope I wasn’t assuming a coupled model (except hoping for one between warming & positive feedbacks). I was imagining that they feed in different emissions amounts into the warming models & thus the different scenarios (the models working very well with small confidence intervals). And then the economists taking their scenarios and feeding them into their own models-of-sorts to see how these might impact our economic situations, and for each climate story coming up with various econ stories, because if climate is complicated, the econ aspects become even more complicated with wild card factors.

And I was dead serious (tho exaggerating) re $trillions in diamond or food. Bec macroeconomics does not really distinguish between these. It does not address what is biologically needed to sustain life. And even microoeconomics only gets at our desires, not our biological needs.

Which is why I would never leave the world’s fate in the hands of neoclassical economists alone. Biologists and others need to weigh in on how GW will impact the world.

And when I say “prudent” I in no way refer to my own risk (tho from experience I’ve found I only save money without reducing living standards by reducing GHGs — that’s just a plus). Prudent means for the entire world into its distant future. My sole motivation is to reduce my killing of people & other biota now and for many millennia. So the prudent path for me is to reduce GHGs as much as possible.

If others don’t mind killing people willy nilly now & into the distant future (bec they are having too much fun living wasteful, inefficient lives — they sort of remind me of those nasty boys who delighted in kicking down my sand castles), then that’s their bag. I’d only hope more people and governments would choose good rather than bad for the sake of the world and for their souls.

RE #249, I feel funny about “carbon offsets.” I think it’s fine to give carbon offset gifts — like giving people CF bulbs or low-flow showerheads, rather than traditional gifts or charities.

However, we must actually reduce our GHGs, not simply buy the right to spew them bec supposedly someone else is reducing for us (they may have thrown that CF bulb away, for all I know).

So carbon offsets can be used, but mainly as carbon offset gifts – the gift that keeps on giving. But instead of buying offsets to drive the same as usual, why not move closer to work, or take a shorter vacation, or run multiple errands, or turn off the motor in drive-thrus. Or buy an EV and plug it into your all wind power electricity (that’s what I hope to do as soon as such vehicles are available at an affordable price — which they should be, since they are so much more simple than ICE cars).

Then buy those offsets anyway to help others reduce.

re Steven Mosher:

Put another way. We cant afford to get that hot, so we won’t. Behavior will change, or people are not rational. And I refuse to be a fascist and bleive that people are not rational.

Unfortunately, people are not always rational, and large aggregations of people are often not rational. Your assertion that this observation makes me a fascist speaks more to you limited observation of the world than to my political leanings.

First, if people were rational, the US wouldn’t have 30,000 deaths from drug abuse every year, nor would we arrest 2 million folks on drug charges. If markets were rational, we would not have crashes like 1929 or 1987.

You are right that behavior will change, but the obvious effects of AGW lag the causitive bahavior. In the case of sea level rise, it may well go on for 800 years after the behavior stops. If there are hidden triggers in the system that amplify warming (and it takes a lot of faith in a lenient, protective God to believe there are none) then we are in deep trouble before the mass of humanity sees the need to change.

Finally, you say “In fact, one could say that increasng your emissions is POSITIVELY CORRELATED with wealth. “ This is simply not true. In the decade or so after the 1973 oil shock, Japan decreased energy consumption by 1/3 while doubling GDP. Even today, Japan, Britain, Germany, and France produce about half the CO2 per capita that the US does.

The thing that frustrates me the most about the discussions of AGW is assumption that mitigation will depress standards of living. That is only true if we are too dense to imagine, and then develop alternate ways to generate and consume energy. The country that develops effective renewable energy sources first will be more prosperous than the rest of the world for generations. The other mostly ignored factor in the economic debate is what the status quo costs. The US ships about $30 billion per month to pay for imported oil. We spend (by my calculations) about another $20 billion a month to protect overseas oil supplies. Western dependence on Middle Eastern oil funds Islamic terrorism.

Conservation and renewable energy sources are the only path to energy independence. Energy independence solves a lot of our current problems.

re. 255

It’s at least as much about pointless wastage. The main reason European countries use well under half as much energy per capita as the US is that they don’t waste as much, but even in Europe we waste a ridiculous amount. Over 80% of houses in the UK aren’t insulated properly. Over 90% use inefficient light bulbs. A huge percentage of people in the UK go on regular car trips of well under a mile (I’ve forgotten the percentage but it’s incredibly high). Cycling or walking for such short journeys wouldn’t only save energy but would increase health and reduce traffic jams. Most shops and offices leave large numbers of incandescent lights on all night (frequently halogen lights, the most inefficient ones of all), even in well lit street with CCTV. Most street lighting could be solar and is not. Our electricity grid is incredibly inefficient; a decentralised grid could increase efficiency by around 40%. Almost all existing cars could be converted to LPG for a fairly low outlay that would typically pay for itself in 2-3 years, and that would reduce emissions from cars by 20%. New cars, even without using alternative fuels, could use fuel around 30% more efficiently than they do on average, using existing technologies. Glorification of SUVs has nothing to do with standards of living, and there are many fuel-efficient cars that are a pleasure to drive. Most people throw away several plastic carrier bags every time they go shopping, when they could get a couple of sturdy shopping bags that last a lifetime and use them. I could give hundreds of other examples. We could cut our energy usage dramatically with no technology breakthroughs whatsoever, and with no reduction in living standards whatsoever – it’s just a matter of wanting to. At the moment most of us simply don’t care enough to want to, although many of us pretend that we care.

RE. 254, you can’t reduce your emisssions to zero. Reduce them as much as you feel you can, and offset the rest.

Re. 255

Even more that is only true to the extent that we continue to be addicted to waste and inefficiency. Living standards in Western Europe are broadly similar to those in the US but per capita CO2 emissions in Western Europe are less than half those in the US, and that is almost entirely due to waste and inefficiency. And even in Western Europe waste and inefficiency is extraordinarily high. We could probably cut emissions in Europe by 50% purely by reducing waste and inefficiency, with no need for any new technologies at all. But the political will isn’t there currently.

As countries such as the UK (eg through its Climate Change Bill and associated measures) move to implement high-impact energy-conservation and efficiency, resource efficiency and waste minimisation, green business strategies etc, the US seems (from the outside) to remain entrenched in old-world dogmas that to go green is bad for business and bad for the economy.

If going green (through integrated implementation of the above plus implementation of businesss ecointelligence etc) can strip huge costs out of a business and improve competitiveness and facilitate entry into and formation of the emerging green markets, as well as (when implemented across the economy) delivering carbon downsizing on the massive scale required to suppress climate change and its impacts as far as possible, then it must make business sense and planet sense.

The longer the US decides not to implement full-scale high-velocity carbon downsizing on a national scale, the greater the opportunity for its businesses and industries to be competitively zapped when world markets transition. Making an ultra-fast transition to becoming ultra-low carbon is equivalent to becoming highly competitive and at the same time brings powerful positive benefits to climate change mitigation.

Those who argue that the US should resist attempts to maintain / become competitive through carbon downsizing have not really thought it through. They might not put it in those terms – for example, they might argue that climate change mitigation is too costly – but the effect of their digging-in-of-heels and addiction to the past is the same.

Finally, to keep this post on thread (IPCC sea level numbers), like the ice melt that is flooding down the moulins, there is a phrase that one could use about where US businesses and industries might flush if its leaders don’t rise to the global competitive challenge and carbon downsizing opportunity.

#255, fully agreed. When I first started outreaching to people in the early 90s to reduce their GHGs cost-effectively (& save money, without lowering living standards, as I had done & and knew thru experience was quite doable), and in that way reduce harm from GW & other environmental problems (& other – as you mentioned – harms & expenses), I thought all I’d have to do is tell people, start the ball rolling, then get back to “my life.”

I thought the regular people (not drug addicts, of course) were rational enough to want to save money or do good (at no cost, even savings). But alas alack, they simply are not rational! I can’t even get goody-two-shoes religious people to reduce GHGs cost-effectively for the sake of saving the world for their progeny. The anti-abortion activists seem to be the most opposed to even believing GW is real, and couldn’t care less about all the other harms, such as “natural” abortions from local pollution. It is the hardest nut to crack I’ve ever experienced.

OTOH, it was not rationality that motivated me, but a profound conversion experience or change of heart. I was reviewing the film IS IT HOT ENOUGH FOR YOU? (about GW) in 1990, a film I had shown my classes several times. Nothing new. All of a sudden during the part about drought starvation in Africa I cried out (internally), “Why don’t they do something about this?” Then it hit me like a tons of bricks. “I’m the one causing this. I have to do something.”

That was around Ash Wednesday of 1990. I spent Lent in anguish not knowing what to do, caught up in structures of high GHG emissions (knowing my husband would not go along with a primitive lifestyle). I was the Good Thief on the cross, repentant but unable to correct my fault, until I realized I was the Roman soldier pounding in the nail – forgiven, but unable to stop my killing.

Then the week after Easter I went to the Earth Day fair & watched Earth Day TV programs, and began to realize there were solutions. But it was mainly many many little things (turning off the water while brushing teeth, etc), and a few big things.

Over the years I reduced by about 1/3, then went on Green Mountain 100% wind powered electricity. And I’m counting GHGs from all things, not just gasoline & electricity. All products and water have GHG components. REDUCE, REUSE, RECYCLE can go a long way to reducing GHGs. And now I’m awaiting plug-in hybrids, which will be a high cost for us, but our savings over the past 17 years from reducing GHGs should help off-set that cost.

So rationality does NOT work. Our only hope is if many many people & businesses & our gov have conversion experiences that touch their hearts, open them to reducing GHGs. The actual changes and implementations of GHG reduction measures then become easy by comparison.

#259, that catchy about the moulins. “Don’t flush the world down the moulins.” Then let people ask, “What are moulins?” Then let them find out.

And just in time for Earth Day.

Well, I can’t begin to answer all of the various comments so, I’ll just point out a few things.

First, as a stated above my main concern is not with the climate science or the models used to make future projections. But every good modeler knows “garbage in; garbage out. I would recommend that everyone read the SRES. you can find it on the IPCC site. Here is a link to the emmission scenarios

http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc/emission/116.htm

Note the huge spread in emission assumptions. What this indicates to me is a very large uncertainty in the future of emmissions. So, who decides what scenarios to use. Some of them are scary; sme benign

Now, as I read it the models are fed with data from the scenarios. The output of the models do not feedback into the scenarios. I’m somewhat suspect of this.

Second, the scenarios are broadly classified into 2 dimensions. The dimension that intersts me is the A/B dimension. In the A scenarios people are driven toward economic development. In the B scenarios the drivers are Enviromentalism, roughly speaking. So, for example in A1F1,

the scennario that shows the highest sea level rise, there is a global focus on economic development and there is a focus on Fossile fuels.

According to this scenario sea level goes up between .26 and .59 meters.

In the B1 scenario there is a global drive ( the one indicates global as opposed to regional ) toward eniroment concerns. And here you see a rise of .18 to .38 ( i think the average over the past 100 years is something like .2)

Anyways, these two scenarios are given equal weight. Now read through the AIF1 scenario. In shrt form, it assumes the entire world will start to follow a US strategy with regards to economic development and fossile fuel usage. Not very sensible, not very probable. Yet, it’s given equal weight and it drives the highend of the estimates in the models. Put anotherway, AIF1 is not realistic because its not sustainable. I suppose one includes it to motivate folks, but it kinda verges on a scare tactic.

Now, with regards to the correlation between wealth and getting hotter.

I’ll go look through the reports again. my initial impression from glancing at a couple numbers was that wealthier (global GDP) was warmer, and poorer was cooler. If true ( i’ll double check) then this also seems odd since a bunch of folks here seem to argue just the opposite. If being green were to lead to a poorer future, then of course one couldn’t rationally convince people to do it. One would have to scare them. The point is these data sets drive the models. Only goofballs question the science within the models, but it seems we ought to have a glance or two at the data driving them. At this point I just have a bunch of questions. I don’t see it discussed much. I could be wrong so I was hoping somebody else here had actually looked through the input data.

Steven, I believe that the wealthier vs. poorer look mainly at short term wealth production, while the hard times fall in the medium to long term. Also, if you think the rest of the world is unlikely to follow the US example of short-term thinking, then you have a much rosier impression of humanity than I do. Humans do a poor job of perceiving risk–especially when the risk may seem a long way off. And the recent IPCC report can be looked at two ways. An altruist sees an assertion that the hardest hits will knock the poor and thinks we must address the problem or help the poor deal with it. One who is less altruistic thinks, “Hmm, I’d better not be poor.” Which attitude do you think predominates within our species.

As to future supplies of fossil fuels, we have plenty of cheap dirty coal to bring about the toasty, warm future envisioned by the IPCC–and worse. This is the path we are on now, with roughly 40% of humanity in India and China VERY energy hungry and the US showing no sign of diminishing thirst for oil and othe cheap energy. To date, we have shown no more intelligence than a colony of yeast in fermenting grape juice. And I doubt that we will produce a good vintage.

> AIF1 is not realistic because its not sustainable.

But it describes business as usual, and it describes what both India and China are doing now. That’s a big enough part of the world to be considered as a high end estimate.

Nothing highly profitable is sustainable — natural stocks grow at the average three percent a year, broadly speaking. An economy growing faster than that is an extractive economy, able to generate a surplus to buy up other resources and extract those later.

Remember the suggestion that the best economic approach to whaling was to liquidate the resource and put the money in the bank, because interest rates are higher on money than the rate of growth of whales.

Returns on investment on energy conservation etc are much greater than returns from the stock market.

Re #262. I think Steven has a good point, insofar as (AFAIK) none of the climate models include the results of adaptation, which could modify climatic outcomes considerable (and in either direction). For example, farmers and other land managers will certainly respond to climatic change (indeed, are already doing so), and to government or other mitigation initiatives, with complex consequences. Integrating land use change into climate models may be the next major step in improving them, but will be very hard.

Re #260, #263. I think you are both too pessimistic. The greatest ground for optimism is that objectively, all individuals and institutions concerned about what happens more than two or three decades ahead now have a central common interest – cutting GHG emissions fast. What’s more, agreement between a relatively small number of governments could make a big difference – the G8 plus 5 major “developing” countries, representatives of which are to discuss climate change this summer, would certainly be enough. Indeed, even if a few of these were to refuse to cooperate, a sufficiently large and powerful coalition, able to exert economic pressure on all other states to fall in line, might still be possible. Of course, all are likely to want others to make the biggest sacrifices, no agreement reached this year is likely to go anything like far enough, and given Bush’s baleful influence, the chances of any agreement at all before 2009 are slim, but the political shift that is currently going on should not be underestimated – consider the views of likely candidates in the 2008 US presidential election, the way environmental issues have shot to the top of Australia’s political debate, the Stern report and its repercussions in the UK. Sufficient GHG emission reductions are going to require radical socio-political change, but the shift in direction has begun, and I believe it could be fast enough.

RE #263.

Thanks Ray.. I’ll make a couple points. See what you think. I don’t think you’ve read the SRES. Have a look. Anyways You wrote:

“Steven, I believe that the wealthier vs. poorer look mainly at short term wealth production, while the hard times fall in the medium to long term. Also, if you think the rest of the world is unlikely to follow the US example of short-term thinking, then you have a much rosier impression of humanity than I do.”

Interesting. So you thnk that short term thinking is wrong. You think most people will think in a short term way, ie follow the US, So you would propsoe that a few people decide what is best for our long term interest? Put another way, you think that I have a rosy view of humanity because I believe they can figure out their rational interest. So are some people just smarter at figuring out my interest for me? and how do we decide who these deciders are? Can’t ask the stupid short termed thinkers now can we? I mean if they can’t spot their interest how could they pick leaders? Hmm..The main reason I think people can’t follow the US down a Fossil intense path is the MODELS say such a path will cause enormous economic impacts. Simply put, A1F1 assumes developing areas pursue our path. But the impact statements state the opposite. That those ares will be hit heaviest by warming. This relates to my initial complaint that the inputs to the models are not coupled to the outputs. But hey, thats looking at the long term.

And you go on

“Humans do a poor job of perceiving risk–especially when the risk may seem a long way off. And the recent IPCC report can be looked at two ways. An altruist sees an assertion that the hardest hits will knock the poor and thinks we must address the problem or help the poor deal with it. One who is less altruistic thinks, “Hmm, I’d better not be poor.” Which attitude do you think predominates within our species.”

So essentially this is the same argument. Most people can’t assess risk.

Most people don’t care about others. Therefore, some privaledged people will do it for them. Sorry. If most people can’t assess risk and won’t be altrusitic, then who will decide? And who will pick the deciders?

According to you The majority of people of can’t assess risk or be trusted to do the right thing. A few posts back I think I called this philosophy fascist. That was overly harsh. let’s call it elitist.

Don’t know why I did that. had a hunch I suppose that people would come out and say… most people are stupid, most people are evil, trust the master race. Good thing nobody took that bait!

And then you wrote:

“As to future supplies of fossil fuels, we have plenty of cheap dirty coal to bring about the toasty, warm future envisioned by the IPCC–and worse. This is the path we are on now, with roughly 40% of humanity in India and China VERY energy hungry and the US showing no sign of diminishing thirst for oil and othe cheap energy. To date, we have shown no more intelligence than a colony of yeast in fermenting grape juice. And I doubt that we will produce a good vintage. ”

My mistake. I wasnt speaking to the SUPPLIES of Fossil fuels. I was speaking to a different issue. If china and India Follow the US, we will see economic impacts ( droughts, famine, dislocation, disease, see the impact report) before 2100. Simply, the economic activity in A1F1 is not sustainable because of the damage it inflicts. A1F1 assumes that fosile fuel can be consumed without enviroment damage and without economic impact. Like I said the climate outputs of the model are not fed back into the dataset.

In short, A1F1 can’t happen. To put it another way, you can’t have it both ways. You can’t use a dataset (A1F1) that assumes you can emit with impunity and flourish economically ( A1F1 has some of the highest GDP) and then argue that emitting with impunity leads to economic disaster.

Ah well, you can argue that, but that’s an emotional scare tactic. For some views of humanity these tactics are justfied.

Lets see. basically you said people are stupid. Then you try to convince me ( i think I’m human) of something. But if I’m stupid, how can I be convinced? especially by an argument that people are stupid.Now, I can be threatened. You’ll go to hell. I can be bribed. You’ll go to heaven. But, if I’m stupid, then I can’t be convinced. Isn’t it kinda self defeating from a rhetorical point of view to convince your audience by telling them that people are stupid.

Oh ya, except for us smart guys.

Gee, Nick, did you see what China, Russia and Saudi Arabia managed to do to the recent Summary for Policy Makers–only remove any reference to scientific consensus. The fact remains that to date no country has undertaken any policy that meaningfully reduces CO2 emissions. So, I really do not find any comfort in the fact that politicians are making the right noises. They’ve been making the right noises on healthcare in the US for decades.

re: #266

I don’t think the world is inherently doomed either, BUT:

a) Reading Jared Diamond’s “Collapse” doesn’t make one believe that people consistently are able to make good long-term decisions. Perhaps we know more now, but it is still clear that many people are able to ignore even strong evidence.

b) The AGW problem seems unusual, in that humans are just not used to dealing with causes whose lag-time to effects are decades/centuries. Many people think that AGW can’t be true because the temperature rise in the 20th century didn’t immediately track the CO2 buildup, i.e., they don’t understand the lag-times and inertia in the system.

Interestingly, moulins are a key plot point/device in my novel Warm Front. I think I used them in a way no one else has.

Let me truthanize everyone. THE FACTS: 1) Global climate (and sea level) has NEVER remained constant. It is ALWAYS gradually changing in one direction or another. 2) Over the last 20,000 years, the earth has warmed enough to raise sea level 400 feet WITHOUT ANY ANTHROPOGENIC INFLUENCE! 3) Even if we abandon the planet or become extinct, SEA LEVEL WILL CONTINUE TO RISE! (just probably not as fast). 4) We can’t stop it, nor should we try (it’s NATURAL). While I am VERY MUCH in favor of limiting/reducing GHGs, preserving our oceans, and reducing habitat loss worldwide, it is a waste of time and energy to worry about a piddling 18 to 59 cm rise in sea level over the next 100 years. Instead of worrying about what causes sea level change and how to stop it, (because WE CAN”T!), we should figure out how to manage it and live with it. “let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance” FDR

[Response: Hemlock is natural but I wouldn’t advise eating any. The issue is whether we can avoid really big sea level rises due to melting ice sheets – if that starts to happen, there will have been nothing ‘natural’ about it. -gavin]

#264.

Hi hank. Thanks for your thoughful comments. Have a look at the SRES. It makes for good reading. Just google SRES IPCC. Since you were kind enough to respond, I’ll make a few comments back. Ok?

You wrote:

“But it describes business as usual, and it describes what both India and China are doing now. That’s a big enough part of the world to be considered as a high end estimate.”

Yes, that is roughly correct. My issue is this. The SRES dataset make assumptions for the next 100 years about emmissions. These emission assumptions are driven by scenario assumptions. Like so: assume china, India and the whole developing world follow the US….. they spew C02 like the US does… over time.

From this Assumptipon about the futur, you get, roughly, a decade by decade projection of emmissions.So much C02. so much methane, land use like this, deforstation like that, cement production like this, population like so ( fun stories, you should read them. population control SHOULD be high on our agenda, according to the data). But in A1F1, by 2100 we are all hot and wet. ( ok sorry about that, but we all need to laugh ok)

This is issue.

INTERMEDIATE RESULTS. ( say 2050 results) of climate models are not fed back into the datasets to make adjustments to the economic activity assumptions, land use assumptions etc underlying them. In short, A1F1 assumes that people will continue to act in stupid, ignorant destructive ways when their countries suffer. When their countries are drought ridden, disease ridden, flooded, refugee ridden, hurrican ridden..In short, A1F1 assumes that people are too stupid to realize their behavior is destroying the world they live in. Even when they are knee deep in sea water. Even when malaria kills their kids. Even when…. If people are this stupid, they need to be controlled and governed by those us us who know better.

They will appreciate it. In the end. We should control them… Opps.

A1F1 assumes that people can continue to act in these ways, despite being, parched, infested,drowned, and living in tent cities. Huh? Global warming will have an impact on economic activity. In the AiF1 scenario, it does not. In that scenario everyone burns carbon and gets richer. What the F over?. Why input Junk assumptions into validated models? WHY?

Now, we know that if the A1F1 predictions are right, if our coast areas flood, that economic activity WILL change. But….A1F1 scenarios predict GDPs at TWICE the level of B2 GDPS (futures where we think global act local) So, I find this funny. The hot future under water is projected to be better off economcally. Nobody beleives this is a realistic future.

Then you wrote:

“Nothing highly profitable is sustainable — natural stocks grow at the average three percent a year, broadly speaking. An economy growing faster than that is an extractive economy, able to generate a surplus to buy up other resources and extract those later.”

I believe the A1F1 scenario.. maybe the A1B is the 3% per year model. BUT you make my point. Thanks. A1F1 assumes sustainable economic activity over the next 100 years, regardless of enviromental impact. You are right A1F1 is a crock. Opps, that was my point.A1F1 philosophy is this: growh rate has been 3% since 1850, it will be 3% until 2100. REGARDLESS OF WHAT WE SPEW. We will emit like hell, and this growth rate will not be impacted. Climate be damned. That is the asumption of A1F1, and you know it’s false. I call that a fairy tale.

If you give people a choice between B2 ( 200-250 Trillion GDP) and A1 ( 500-550 Trillion GDP) only irrational fools will pick the green B2 . Hmm, I didnt say that. maybe I should argue FOR A1F1. Hot wet rich and dirty.

But.. I wonder..let me simplify this because I have not been clear… From 100000000 feet:

F(Economic activity) = emissions;

F(Emissions )= warming;

F(Warming) = sealevel;

F(sealevel ) = economic activity;

To explain the last. F(sealevel) = economic activity: New york under water. Flooded coast ain’t good for bidness. we could also substitute F(climatechange) = economic activity. Hot drought ridden land doesnt grow food!. See the impact statement.

Now, clearly the entire model insinuates that economic activity ( choice of fuel types, population, etc etc) drives carbon, which drives the enviroment, which drives economic activity. So feedback. The whole POINT of policy recommendations is that there is a feedback loop. BUT, the modelling approach doesnt use a feedback loop. The climate science is great. The policy loop is disconnected. So, you can predict debates in that area. See, we are having one. Confirmed.