Just when we were beginning to think the media had finally learned to tell a hawk from a handsaw when covering global warming (at least when the wind blows southerly), along comes this article ‘In Ancient Fossils, Seeds of a New Debate on Warming’ by the New York Times’ William Broad. This article is far from the standard of excellence in reporting we have come to expect from the Times. We sincerely hope it’s an aberration, and not indicative of the best Mr. Broad has to offer.

Broad’s article deals with the implications of research on climate change over the broad sweep of the Phanerozoic — the past half billion years of Earth history during which fossil animals and plants are found. The past two million years (the Pleistocene and Holocene) are a subdivision of the Phanerozoic, but the focus of the article is on the earlier part of the era. Evidently, what prompts this article is the amount of attention being given to paleoclimate data in the forthcoming AR4 report of the IPCC. The article manages to give the impression that the implications of deep-time paleoclimate haven’t previously been taken into account in thinking about the mechanisms of climate change, whereas in fact this has been a central preoccupation of the field for decades. It’s not even true that this is the first time the IPCC report has made use of paleoclimate data; references to past climates can be found many places in the Third Assessment Report. What is new is that paleoclimate finally gets a chapter of its own (but one that, understandably, concentrates more on the well-documented Pleistocene than on deep time). The worst fault of the article, though, is that it leaves the reader with the impression that there is something in the deep time Phanerozoic climate record that fundamentally challenges the physics linking planetary temperature to CO2. This is utterly false, and deeply misleading. The Phanerozoic does pose puzzles, and there’s something going on there we plainly don’t understand. However, the shortcomings of understanding are not of a nature as to seriously challenge the CO2.-climate connection as it plays out at present and in the next few centuries.

The use of the more recent Pleistocene and Holocene record to directly test climate sensitivity presents severe enough difficulties (discussed, for example, here), but the difficulties of using deep-time Phanerozoic reconstructions for this purpose make the Pleistocene look like childs’ play. The chief difficulty is that our knowledge of what the CO2. levels actually were in the distant past is exceedingly poor. This situation contrasts with the past million years or so, during which we have accurate CO2. reconstructions from ancient air trapped in the Antarctic ice. Obviously, if you don’t know much about how CO2. is changing, you are poorly placed to infer its influence on climate, even if you know the climate perfectly and nothing else is going on besides variation of CO2.. But, neither of these latter two conditions are true either. Our knowledge of climates of the distant past is sketchy at best. Even for the comparatively well-characterized climates of the past 60 million years, there have been substantial recent revisions to the estimates of both tropical (Pearson et al., Nature 2001) and polar (Sluijs et al, Nature 2006) climates. Most importantly, one must recognize that while CO2. and other greenhouse gases are a major determinant of climate, they are far from the only determinant, and the farther back in time one goes, the more one must contend with confounding influences which muddy the picture of causality. For example, over time scales of hundreds of millions of years, continental drift radically affects climate by altering the amount of polar land on which ice sheets can form, and by altering the configuration of ocean basins and the corresponding ocean circulation patterns. This affects the deep-time climate and can obscure the CO2-climate connection (see Donnadieu, Pierrehumbert, Jacob and Fluteau, EPSL 2006), but continental drift plays no role whatsoever in determining climate changes over the next few centuries.

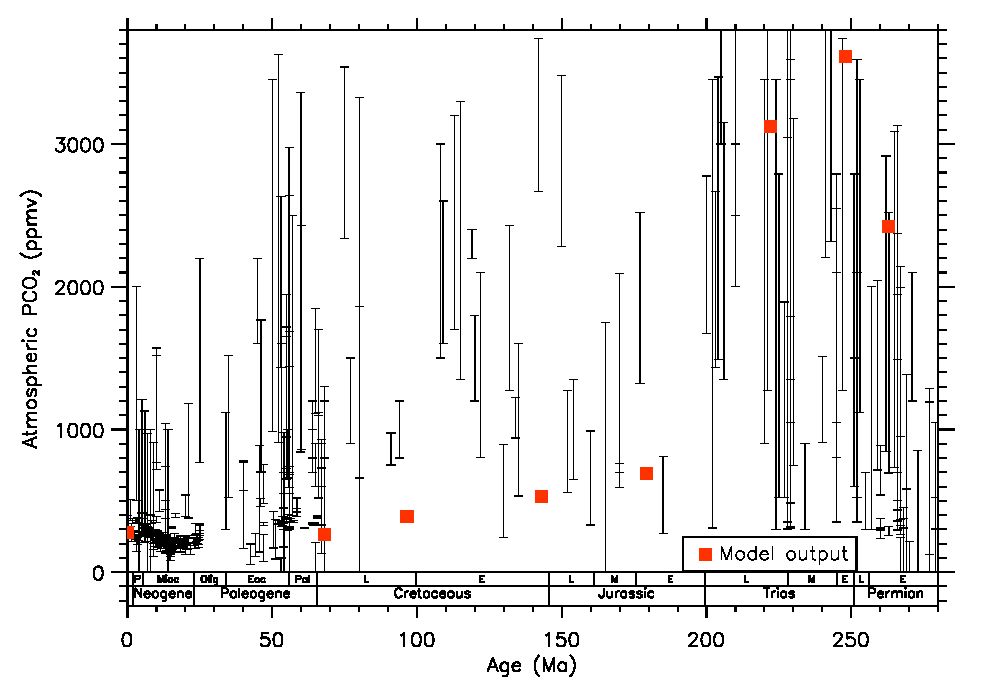

Let’s take a closer look at the question of CO2 variations over deep time. In contrast to the situation for the late Pleistocene, there is no one method for reconstructing CO2 at earlier times which is fully satisfactory. Methods range from looking at carbon isotopes in microfossils to looking at the density of pores on fossil leaves, with many other exotic geochemical tracers (e.g Boron) coming in in recent times. There is also some data for the very early Earth associated with the CO2 conditions under which certain exotic minerals (uraninites and siderites) form. None of the methods is unambiguous, and none provide information about other greenhouse gases that might be playing a role (though there may be some hope to do something abou methane). As an example of the difficulty faced by the field, take a look at the compilation of various estimates of CO2 since the Permian presented in the following figure (From Donnadieu et al, G3, in press; the red squares come from an attempted geochemical model fit to the data. The data set comes from Royer et al. (2004) and is available here).

By the time one gets back to the Permian, the error bars are huge. At earlier times, the estimates are even more problematic. Broad’s article does make reference to a very interesting paper by MIT’s Dan Rothman, writing in PNAS. This paper attempts a peek at the CO2 over the past 500 million years, using a clever and novel reconstruction technique. It is innovative, but far from the last word on the subject. Broad inappropriately cherry-picks Rothman’s statement that there appears to be no clear connection between warm climates and CO2 (except in "recent" times, about which more anon). However, Broad’s article neglects all the caveats in the paper, which clearly point to the real problem being that the reconstructions of CO2 and climate over such time scales are so uncertain that it’s not clear that the data is up to the task of teasing out ssuch a connection.

Even in Rothman’s reconstruction, during the past 50 milllion years — when the data is best and continents are most like the present — the long term cooling trend leading into the Pleistocene is clearly associated with a long term CO2 decline. This is not our main reason to infer that increasing CO2 will warm the climate in the future, but insofar as the data supports CO2 decline as a main culprit in the long slide from the Cretaceous hothouse climates of 60 million years ago to the cold Pleistocene climate, it also lends weight to the notion that as industrial activity busily restores CO2 to levels approaching those of the Cretaceous, climate is likely to turn the climate clock back 60 million years as well. From Broad’s flip dismissal of the CO2-climate connection in the "recent" part of the record, the reader would never guess at the length and particular significance of this period.

And then, too, the tired old beast of Galactic Cosmic Rays (GCR) raises its hoary head in Broad’s article. The GCR issue has been extensively discussed elsewhere on RealClimate (e.g. here and here) On one level the GCR idea is another instance of the problem that Phanerozoic climate variations may have had many causes, giving rise to a false appearance of decorrelation between climate and CO2. Whatever role GCR may have played in deep time climate, the climate of the past century and its attribution to CO2 is a wholly different kettle of fish, since in modern times we have direct observations of GCR and they are not doing anything of a sort that would cause the observed warming — to say nothing of the fact that one would still have to argue away the basic radiative physics which makes CO2 affect the planet’s radiation budget. We repeat: There has been no recent trend in cosmic rays that could conceivably account for the recent warming, even if the GCR proponents were right about the physical mechanism underpinning their theory. This is made abundantly clear in this recently published article. Further, whatever was going on in the past, the present observations do not support the supposed cloud-GCR connection that is supposed to mediate the climate effect. That’s not the end of the story, for there are also severe methodological difficulties in the way the GCR proponents have attributed Phanerozoic change to GCR rather than CO2, and also severe conceptual difficulties in the supposed physical link between clouds and GCR.. Some of these difficulties may ultimately be resolved and allow a more fair test of the possibility that GCR influences played some role in the past. Surely, the play given to Veizer and Shaviv in the context of Broad’s article is an instance of false balance of the worst sort. The possibility that the GCR theory may play some role in deep-time Phanerozoic climate is eminently worthy of further consideration, but the way its major proponents have used the theory in attempts to undermine forecasts of near-term warming is unjustified.

Besides the broad-brush errors discussed above, Mr. Broad commits a number of lesser climatological faux pas, in areas where he really ought to know better. He refers to CO2 as "blocking sunlight" (whereas it’s actually thermal infrared which CO2 affects). He says that CO2 traps heat "in theory." This is a lot like saying that a bowling ball dropped from an airplane will fall to the ground "in theory." There is indeed a theory involved in both cases, but the use of the phrase gives a completely wrong picture of the certainty of the phenomenon. There is no more doubt about the heat-trapping effect of CO2 than there is about the physics that causes a bowling ball to fall. Broad also says that the greenhouse effect of CO2 "plateaus" at high levels. This is a botched attempt to describe the well-known logarithmic radiative forcing of CO2, incorporated in every climate model since the time of Arrhenius. There is no "plateau" where CO2 stops being important. Every time you double CO2, you get another 4 Watts per square meter of radiative forcing, so that the anticipated climate change between present CO2 and doubled CO2 is comparable to that between doubled CO2 and quadrupled CO2. In fact, as one goes to very high CO2 levels (comparable to the Early Earth), the radiative forcing starts to become more, rather than less, sensitive to each further doubling (something that can be inferred from the radiative forcing fits in Caldeira and Kasting’s 1992 paper in Nature).

Let’s not lose sight, however, of the essential conundrum posed by Phanerozoic climate, particularly by the warm climates of the Cretaceous and Eocene. Current climate models do not reproduce the weak pole to equator gradients believed to characterize these climates, and have trouble warming up the polar climates enough to melt ice and eliminate continental winter without frying the tropics more than data seems to permit. Maybe there’s something wrong with the data, or maybe there are currently unknown amplification mechanisms that make the switch from a moderate Holocene type climate to a hothouse more catastrophically sensitive to CO2. This truly must give us pause as we contemplate the experiment of doubling CO2 in the next century. It’s certainly an experiment that would help to resolve some of the mysteries of Phanerozoic climate, but we’d on the whole prefer to see the mysteries resolved by improved studies of past climate instead.

Update: See Tom Yulsman’s commentary on this post and the broader issues.

Surely it isn’t true that “Every time you double CO2, you get another 4 Watts per square meter of radiative forcing,” Eventually, the CO2 IR bands are full and adding more CO2 has no effect. The question is, when is “eventually”?

[Response: The CO2 bands may fill up at low levels, but the trick is that there’s always a part of the atmosphere tenuous enough that the CO2 bands are unsaturated, and the radiation comes from up there (where it’s cold). A complication in thinking about the effect of CO2 on outgoing infrared is that adding CO2 actually tends to make the stratosphere colder, which gives you an additional reduction in OLR (for fixed surface temperature). Long before you get to the point where the stratosphere is optically thick, though, you enter the regime where the weak CO2 bands start to become important, and the radiative forcing per doubling increases — that’s at around 20% CO2 in the atmosphere, which is relevant to the Early Earth, but not to the near (or even far) future. By the way, it takes a whole darn lot of CO2 to saturate all the CO2 bands. Even Venus isn’t really saturated. On Earth and other wet planets, the thing that saturates the absorption is the water vapor, which starts to be completely opaque for infrared for saturation vapor pressures corresponding to temperatures around 300K. –raypierre]

Nice post. I too had noticed that he falsely states that as CO2 levels rise, the climate effect reaches a “plateau.” I also noticed that the headline and first several paragraphs give the impression that new results will overturn modern climate theory, but the latter part of the article is much more moderate.

You guys at RC have been busy lately! Thank goodness, because the contrarian forces have been busy too.

I wonder just how much the emergence of the first terrestrial rain forests in the Late Devonian and Carboniferous had a bearing on the glaciations that occured around that time, and that set in with earnest in the late Mississippian (Carboniferous). I am also tempted to think that the switching from primary aragonite and primary calcite marine cements during the Carboniferous may also have a relationship to ocean pH and therefore CO2.

Anyone have any views?

[Response:An excellent point about the rain forests. The albedo feedback and evapotranspiration could be playing a role, but my feeling is that the biggest effect of vegetation in warm rainy areas would be via silicate weathering. Standard wisdom has it that vascular land plants greatly increase silicate weathering, which would draw down CO2, all other things being equal. The effect of varying vegetation on weathering is not yet in the model in our G-cubed paper. Yannick Donnadieu and I are busily trying to learn enough about vegetation modelling that we can put this effect in the geochemical model. –raypierre]

I just had a chance to check last month’s Scientific American out of the library, found a pretty mind-boggling article on the mechanism that now seems likely to have caused most of the big mass extinctions of the past. It starts with unusual volcanic activity raising the atmospheric CO2 level to about 1000 ppm… leading to a sudden change in ocean chemistry, vast anaerobic bacteria blooms that pour H2S into the air, catastrophic ozone depletion (and it’s a miracle anything survives.)

I’m wondering if the total amount of carbon available on the earth’s surface, in forms that could rapidly get into the atmosphere, might have formerly been less (?) Less carbon tied up in methane clathrates in precarious locations, maybe? Then concentrations of CO2 could have remained high for long periods, making for more uniform temperatures, without (often) passing that 1000 ppm overload mark. (?)

And of course I also wonder how this affects recent discussions here of “how much climate change can we afford?” Temperature increases are one constraint, eventual sea level rises another–but how much CO2 ends up in the ocean might put the problem in a whole different worm-can.

Raypierre

Hmmm?.

The relationship between weathering and vegetation is a tricky one. It is well documented in modern day Sumatra.

In terms of sediment flux- it’s actually semi-arid climates that supply the large sediment fluxes. This is because dense rain forest vegetation binds sediment/regolith and protects it from erosion. Peat is particularly difficult to erode. Also many of the rainforests in the Carboniferous were ombrogenous bogs, with the trees rooted into the underlying peat- not bed rock or sediment.

What is clear is that those Carboniferous rain forests rooted in sandy soils- end up leaching the soil almost to pure qaurtz- giving rise to silcrete palaeosols- known here in Britain as ganisters.

What do you think about the primary aragonite/calcite marine cement flips?.

Very interesting, Ray. Have you gotten in touch with Broad? He is a very professional journalist (a co-recipient of the Pulitzer) and I’m sure would be grateful for constructive criticism. I always hope that when I err in something I write — as we all do — someone would work with me to improve.

George

[Response: Good point. I like to think that journalists covering climate change are routinely reading RealClimate already, but with time pressure and deadlines and all, that’s not a completely safe assumption. I’ve sent Broad an email pointing out our commentary, in case he hadn’t noticed. –raypierre]

“The worst fault of the article, though, is that it leaves the reader with the impression that there is something in the deep time Phanerozoic climate record that fundamentally challenges the physics linking planetary temperature to CO2. This is utterly false, and deeply misleading.”

What would also be misleading would be giving policy makers and the public an impression that we now understand all of the complex, non-linear interactions between all the forcings and feedbacks significantly well to forecast future climate with skill across multi-decadal time. Just because Stefan-Boltzmann and Wein are beyond dispute, the best geological evidence available (most of the last 25% of earths history) tells us that CO2 is not the only game in town. It is the very tricky interaction of CO2 with a number of the other forcings that is really the question. To give one example, the role of aerosols and their associated feedbacks is still incompletely understood, but we know to some extent there is a cooling effect. There might be high aerosols and high CO2 (both can be natural and or man-made), and maybe a cooler than expected climate. What about the feedbacks associated with both? How do they all interact?

[Response: You’re not getting the point. All the uncertainties you point are real – but ask yourself whether they can possibly be resolved using data from the early Phanerozoic with (at best) million year sampling? Obviously not – there are many, many more uncertainties in using deep time records than there are in using the relatively well sampled glacial period, or the present. Thus it will always be the case that while deep time may provide tests for our understanding (the PETM, Eocene, snowball earth etc.), it will rarely (if ever) be able to reduce uncertaintites in present climate – and certainly not for changes at the decadal or century scale level. Others might be able to add to this, but I can only think of one thing that deep time has told us that is of directly relevance to reducing uncertainties today, and that is the 100,000 year timescale for the removal of the excess carbon at the PETM. All the other information is more of a ‘wow, that’s an interesting thing to have happened’ kind. Anyone got anything else? – gavin]

[Response: I myself wouldn’t go quite so far as Gavin. I’d agree with him that deep time isn’t likely to be useful for direct estimates of climate sensitivity in the sense that one teases such estimates out of the Pleistocene. However, the Eocene is the closest thing we have to an example of what a warm world with near-current continental configurations and (probably) high CO2 is like, so the quest to understand it is likely to tell us something about the risks going into a high CO2 world in the future. Its role is to shake loose ideas. For example, if it turns out that polar stratosphericc clouds or enhanced hurricanes are the key to the warm Eocene poles, that gives some additional confidence to our projections about how such things might behave in the future. The way I would put it is that it is unreasonable to demand that we solve all of the grand challenges of climate science (faint young sun, origin of oxygen, snowball Earth, Cretaceous warmth, PETM, warm wet early Mars …) before the models are deemed an adequate basis for justifying action on CO2 abatement. That would take centuries to sort out, and given the lifetime of CO2 in the atmosphere and the rate of growth of emissions, we don’t have the luxury of waiting that long. The examples we have — the current climate, the past century, the Holocene, the Pleistocene — provide more than enough checks and confidence in the prediction that the future warming is real and substantial. –raypierre]

Comment #2 above states

“I also noticed that the headline and first several paragraphs give the impression that new results will overturn modern climate theory, but the latter part of the article is much more moderate.”

This raises one of the biggest challenges for writers of all types, but especially science journalists: how to hook the reader in at the beginning, even if your story’s only about an incremental achievement….isn’t it a good thing that climate change gets so much space in the NYT in the first place?! Compare it to the spin on climate in WSJ editorials…

Re Forrest Curo (4)

Less than what?

From what I know, deserts and glaciated areas were much smaller in the Paleocene than today, subtropical forests extended as far north as Greenland, and the polar regions were cool and temperate.

To me this implies significant;y *more* carbon in the biosphere.

However, other than tectonic activity, there was nothing bringing the carbon trapped in fossil fuels up to the surface. As to methane clathrates – I guess their modern distribution is not well-characterized, and less is known about their distribution in the Paleocene.

Great post! When I read that NY Times piece the other day, I also felt like the connection to modern issues was being oversold. It brings me back to a couple of years ago when I was hanging out on a message board on the Michael Crichton website and a geologist there was harping on this idea that we don’t understand the climates of hundreds of millions of years ago. I am glad to see that the basic arguments I came up with at the times are the ones you give here (data is not very good, lots of other confounding factors like different continent locations, …).

Another thing I also liked to point out, which you have mentioned but could probably use re-emphasis, is the vast difference in timescales. We are trying to make predictions on timescales on the order of 10^2 years. Do we really need to understand things on timescales of 10^8 or 10^9 years in order to do this? Sure, it would be nice to understand everything. But, it seems sort of ridiculous to say that we can’t make predictions on a timescale of 10^2 years without being able to understand and explain what goes on at timescales 6 orders of magnitude longer than this. It seems impressive enough to me that we now have quite good data and some reasonable understanding (albeit with some gaps) of what goes on at timescales up to 10^6 years.

[Response:Your point about timescales is right on. Yes.–eric]

[Response: The greatest overselling of the link between modern climate change and some vague (and statistically not significant) correlation on the 100-million-year time scale must be this infamous press release by cosmic ray proponent Nir Shaviv. -stefan]

Re 5:

If vegetation reduces sediment flux, then why does the Fly river, which drains mostly PNG rainforest, have such a huge sediment flux? Isn’t total rainfall and terrain relief the dominant factor there (and in other high sediment drainages like the Amazon, Ganges, etc.)?

As for carboniferous forest type, isn’t that a factor of preservation? Obviously subsiding bogs with sedimentary accumulation will preserve their forest much better than eroding hillsides.

[Response: In these discussions of vegetation and sediment flux, please keep in mind that I was talking about chemical weathering (silicate to carbonate, primarily), not physical weathering. Vascular land plants affect chemical weathering by pumping CO2 into the soil, and also by changing the acidity of the soil through humic acids. They probably do a lot of other things to the chemical and microbial environment as well. All of this is different from the sort of thing that determines how much sediment is washed into a river. –raypierre]

Re #11:

The Amazon and Ganges have their headwaters in the Andes and Himalayas respectively. Erosion is very rapid in both of those mountain ranges.

> I can only think of one thing that deep time has told us that is of directly relevance to reducing uncertainties today, and that is the 100,000 year timescale for the removal of the excess carbon at the PETM. …Anyone got anything else? – gavin

It seems to show that complex life can survive several thousand ppm CO2. That should counter claims that 600ppm is likely to make humans extinct.

[Response: I was thinking of uncertainties a little more at the forefront of serious research…. – gavin]

[What the record may show is that life can evolve to adapt to pretty large changes, given enough time (hundreds of thousands of years or more). No serious person is predicting “extinction of humans”. The question is not whether humanity will “survive”, but what we will go through to survive. –eric]

Re: #13

It also shows that climate catastrophe can drive a large fraction of complex life forms to extinction.

>Response: I was thinking of uncertainties a little more at the forefront of serious research…. – gavin

RealClimate does a good job of presenting clear scientific arguments of why GW is real, but I think countering some of the hysteria of exagerated claims of doom is also important. Judging by some of the comments at RC, it is clearly needed.

[Response: We do spend a fair amount of time countering exaggerated claims of doom. Many of us have tried to set the record staight on the THC/Ice-age catastrophe idea, and I myself have spend much time pointing out why the Earth is not going to succumb to a Venus type runaway greenhouse. Some of you, however, seem to think that any prediction of severe impact is so unpleasant (or has such unpleasant policy implications) that it must, de facto, be an “exaggerated claim of doom.” There’s not much constructive I can do with that. Very few, if any, scientists are predicting the extinction of human life at 6oo ppm, though once you start messing so much with the whole biosphere, you do have to leave the door open for unanticipated consequences that can be far worse than we think. The predictions of severe impoverishment of the ecosystem and big impacts on the world socioeconomic structure are very legitimate, and in fact are quite legitimate claims of doom. A certain amount of hysteria is justified, indeed encouraged. –raypierre]

I read the article when it came out in the NYT. I was wondering what was big deal. I was going to write a comment on RC and ask about it. You must have read my mind!

From what I learned about climate science and I know about the press, I guessed that it was a minor issue in the scientific community, but the article made it seem like a big drama to get the readers attention. RealClimate confirmed what I thought.

Grant (#2) is right, you guys at RC have been busy lately and its good to see.

[Response: Thanks. It’s nice to be appreciated. I’ve been a bit quiet recently on RC because there’s been a huge upsurge of public interest in climate change, and I’ve been using more of my time on live appearances. –raypierre]

Re-greetings Raypierre, may this be a bad interpretation: CO2 being well mixed throughout the atmosphere can’t have all its molecules saturated at the same time.?? Another question; if there are more molecules of CO2 in the air would this mean more or less OLR in the long run? I am thinking clouds which trap radiation, and tying it with CO2, the problem with clouds is there should be less OLR above them, but with more CO2 the atmosphere should be warmer… Glad I can ask these questions..

[Response: I’m sorry, but I am having trouble understanding your question. Note that when we speak of saturation, we are referring to saturation of the ability to absorb infrared at some wavelength — once you absorb everything, adding more CO2 doesn’t cause any more absorption, since you can’t absorb more than everything. Because of a thing called Kirchoff’s Law, in this circumstance adding more CO2 also doesn’t change emission from the layer, unless you change the temerature. Also, note that when we say CO2 is well mixed, we don’t mean that the number density of CO2 is independent of height, but that the mixing ratio (ratio of CO2 molecules to the rest of the air molecules) is constant. For fixed mixing ratio, there are fewer CO2 molecules per unit volume in the tenuous stratosphere than near the surface. To get an idea of how all this interacts with the temperature profile, take a look at Chapter 3 of my Climate Book. –raypierre]

Boy… when I read that article, I immediately wondered what RC would be saying about it.

So… do the people that know what they are talking about now get in touch with this NYT author & let him know?

I have a friend who works for the NYT, in their Technology section… If you need an “in” to voice your dissatisfaction with the article, perhaps I could get the message there. Or maybe just writing the editor would work?

With respect to chemical weathering 5 & 11- may I recommend “The Kinetics of base cation release due to chmeical weathering” by Harald U Sverdrup, Lund University press, 1990, ISBN 91-7966-109-2

I enjoy this site and learn something new whenever I read all the comments and posts.Everyone who has posted to this site needs to know two things. First, 800 ppm co2 is very possible within the next three hundred years. Second, no one can rule out runaway global warming which will raise the temperature to at least a few hundred degrees F.The unintended consequences of business as usual as we release more and more co2 is completely unpredicatable with current climate models.As the peat moss thaws and polar ice caps melt it is anyone’s guess as to the negative fallout to the climate.A runaway greenhouse effect simply cannot be ruled out given current climate models.End of story.Same with the shutdown of North Altantic current. Anyone who feels confident at estimating the total downside of this event is also sadly mistaken.The fever of a runaway greenhouse effect as relates to the Gaia hypothesis is similar to the human body eliminating a virus or bacterial infection.In this case humanity is the offending virus to Gaia.This has probably taken place on millions of planets in each galaxy. There are approximately 120 billion galaxies, via the Hubble Deep field anaylsis, each with approximately 100 to 300 billion stars.Wherever intelligent life has failed to protect the ecosystem the planet selects against it. Some astronomers, e.g the Drake Equation,think that 95% of planets with intelligent life do not pass this hurdle. Do not think that Earth is exempt from this very common fate for class m planets throughout the Universe which have TEMPORARILY spawned “intelligent” life.

Mark J. Fiore

[Response: Actually, I think a Venus-type runaway greenhouse is one of the few catastrophes one can definitively rule out. See the post that Rasmus and I had on Venus Express some months back. –raypierre]

As one of the people consulted for this article, and the source for the image that they transformed into their figure, I feel compelled to comment.

First, if one sets aside the modern spin issue for the moment, then I think it does do a generally good job of describing what is a significant scientific dispute regarding the Phanerozoic. It is represented by two groups of established scientists publishing in reputable journals. At first glance, it is not unreasonable to think that one could leverage the much larger changes in CO2 and climate that have occured over very long time scales in order to generate an estimate of climate sensitivity. However, the records, to the extent we understand them, suggest that there is not a simple relationship between CO2 and climate. This makes it difficult to know what conclusion, if any, we should draw about climate sensitivity, and that is certainly a legitimate subject for scientific inquiry. Many will say that the Phanerozoic is so long and complicated that we shouldn’t be drawing any conclusion. Some say that the lack of close agreement suggests that the significance of carbon dioxide is less than one might expect. That’s the dispute, and the discussion of that is mostly pretty good.

Some have argued this dispute bears on the modern course of events, which is what makes it sexy and a topic of interest to the public. Though you disagree, as I suspect many climate scientists would, there are a number of published papers arguing that the Phanerozoic data does in fact pose a fundemental challenge to our understanding of the CO2-climate relationship (e.g. Shaviv 2005). However, I suspect that few, if any, scientists have looked at the Phanerozoic evidence and substantially changed their views regarding global warming. I agree with you that it just isn’t firm enough for that.

Returning to the modern issue, I would say that the article does have some spin to it, intentional or not. It suggests that this dispute has or is having an important impact on the scientific community, which isn’t really the case, at least not yet. (Though to be fair it would be hard to discuss the issue at all without suggesting it was important.) My own discussions with Broad did try to draw attention to the views represented by “the evidence of a tie between carbon dioxide and planetary warming over the last few centuries is so compelling that any long-term evidence to the contrary must somehow be tainted”, but obviously it does not play a major role in the resulting text. I also would have preferred that “over geologic time scales” had not been dropped from the front of my quote saying that many factors contribute to climate change.

Ultimately though, I can’t see this as a travesty of science reporting that you apparently do. Its informative and exposes the public to some of the mysteries of deep time and I am glad for that. Does it oversell some things? Yes, but not in a way that I would consider exceptional amongst science reporting. The truth is that as we look back in time there really are many types of climate changes that we simply don’t understand and that does deserve to give us pause, and remember that the sum of all the things we claim to understand is really only a small part of the great variety the Earth has offered us to study. Recognizing that should not be paralyzing though. We have an obligation to move forward based on the undertanding we do have, and take steps to address the likely global warming.

[Response: The article would have been no less interesting if it had simply concentrated on the deep and important mysteries of Phanerozoic climate, without misleading people by drawing out of it all sorts of false lessons regarding future climate. I stick to my assertion that putting the largely discredited arguments of Shaviv and Veizer on the same plane as contributions by scientists like Berner was flat out false balance. The article is not by any means the worst science reporting I’ve seen, and it has some redeeming features. On the whole, though it gives the reader the wrong take-home message, and that’s damaging. –raypierre]

“Standard of excellence in reporting” from the NYT? Really, you must be kidding me.

[Response: I think Ray was referring specifically to their coverage of climate research, which I would agree has generally been very good. Indeed, Andrew Revkin’s seems to get things pretty much dead-on most of the time. On other subjects … I would personally agree that NYT is not particularly a pinnicle of excellence in my book. Having said that, I’m not sure what big newspaper is… –eric ]

[Response:Indeed, it was the science writing I had in mind. I could easily point to spectacular failures of the NYT in the domains of political and national security reporting, but that would risk a flame war that doesn’t belong on RealClimate, if anywhere. The NYT has had its share of troubles with unscrupulous reporters in the past, but seems to be making an honest effort to root out such problems. I’m not aware of their ever having had such problems among their science reporting staff, though. –raypierre]

I am a science writer who finds this discussion of phanerozoic climate and its uncertainties, combined with the dissection of Bill Broad’s piece, quite fascinating. I am posting today a link today to the whole thing for other science writers to see at a website established by the Knight Science Journalism Fellowship at MIT. I’d already posted an item on Broad’s article earlier this week, too, but without much commentary on how he tackled the topic.

And thanks for maintaining an informed, civil, and authoritative discussion forum at RealClimate.

The site with the post on your back-and-forth on the Broad story is ksjtracker.mit.edu. If it’s not near the top, just scroll down or use the search function.

An informative review with one caveat re-the geological time scale.

Throughout much of the Phanerozoic Era one cannot sample accurately timescales of less than one million years. Over these extended time periods it is important to know or predict absolute atmospheric pressure. The major gases, oxygen and nitrogen are likely to have varied ca. -/+2 fold from their present compositions. Surface temperatures are exponentially related to absolute pressure. A trip down to the shore of the Dead Sea, 1000ft below sea level,illustrates the enhanced mean temperature increase(1.5Celsius degrees?adiabatic guesstimate). During the earliest Phanerozoic O2 tensions were probably much lower ca. 1% Present Atmospheric level, presumed upon that level of free O2 required by the hydroxyprolinase enzyme to synthesise the essential amino acid hydroxyproline for synthesis of bone connective tissue and collagen; a the main structural protein of bone.

Finally, mean continental elevations of ca. 800m present day will have varied throughout geologicl history. Much lower mean elevations of continents would also enhance mean surface temperatures.

[Response: Let me say upfront that I realize that science writing is hard. I wouldn’t call Broad’s piece a “travesty,” of science reporting; the previous poster who used this word misread my intent. The NYT article is not an instance of the kind of deliberate distortion and disinformation that is common on the Wall Street Journal editorial page, and even (though thankfully somewhat less commonly in recent times) on their news pages. I think it a case of the requirements of accurate reporting getting steamrollered by stylistic considerations — the desire to make a subject seem important and topical. I think there were ways to make the subject matter seem important and interesting to the reader which would not have risked leaving the reader with the kind of mistaken impression Broad’s article engenders. –raypierre]

I’m assuming the up-coming IPCC will come up with better historical CO2 figures for the distant past than is currently believed.

I’m assuming the 3,000 ppm and higher figures from the distant past will be re-estimated lower in the 450 ppm range?

[Response: Note that IPCC does not do original research – IPCC merely summarises and assesses what is found in the peer-reviewed technical literature. So, we (I’m one of the authors of the paleoclimate chapter of the coming IPCC report) obviously cannot come up with something “better” than the scientific state-of-art, we just describe what this state-of-art is. -stefan]

The article would have been fascinating for me as an ordinary reader — had it as Ray says been about deep time. I would very much like to know who else the author talked to and what he read — the web is a good way to present the citations and footnotes that are missing in newsprint.

“I also would have preferred that “over geologic time scales” had not been dropped from the front of my quote saying that many factors contribute to climate change” — Robert Rohde

Well, there’s your smoking editor. Good grief, the whole point of deep time was snipped out, which rather guts the science, leaving the suggestion this applies at current rates of change.

“…. but aside from that, Mrs. Lincoln, how did you enjoy the play?”

RealClimate’s discussion of the Broad piece was noted on a science journalism Web site called the Knight Science Journalism Tracker–http://ksjtracker.mit.edu. Below is a comment I posted on that site:

Clearly, uncertainty remains the thorniest factor in science journalism. How we deal with it makes most of the difference between good science journalism and poor.

But the folks at RealClimate do take a few careless jabs at Broad. For example, they criticise him for allegedly referring to carbon dioxide as ‘blocking sunlight’ when, in fact, it blocks infrared that began as sunlight, was absorbed on Earth and then radiated skyward as IR. What I see in Broad’s story is that CO2 “blocks solar energy”, which is true.

RealClimate also ridicules Broad for, supposedly, referring to CO2 as trapping heat ‘in theory’. They suggest that Broad is ignorant of the fact that this is an established fact. So it is. But that isn’t what Broad was writing about. He was writing about a time in 1958 and said that climate researchers “knew that excess gas could in theory trap more heat from the Sun, warming the planet and providing a new explanation for climate change.” From the context, it seems obvious to me that Broad was using “theory” to refer to the whole sequence of events in that sentence, including the resulting climate change.

I haven’t examined the whole RealClimate debate on this, but those two points near the top of Pierrehumbert’s commentary suggest to me that he’s trying to color the rest of his argument (which may have considerable merit but is more technical) with a couple of easy jabs at Broad’s grasp of the subject. Those seem to have been wild punches.

[Response: Your comment is misplaced. The piece does not ‘ridicule’ Broad, and the two very minor points you have latched on to are in no way the main thrust of the criticism, are described plainly as ‘lesser’ details, and come in the 8th paragraph of a 9 paragraph piece – how is that ‘near the top’? And CO2 does NOT block solar energy. I would suggest you read and comprehend before you critique – we did. Thanks for the link to the Knight Science-Journalism site – that deserves watching. – gavin]

Re 15 >A certain amount of hysteria is justified, indeed encouraged. –raypierre

That comment appears to be rather irresponsible for a professional scientist and potential fodder for those claiming that many climate scientists are not objective.

[Response: Let’s not read more into this comment than I meant. In a properly ordered world, you’d call 911 and calmly report that an intruder is breaking into your house. The folks at 911 would take you seriously, and send help. Yet, there are some documented cases where the calmness of the caller led to the caller NOT being taken seriously, with tragic results. One can argue that we’re in a similar situation right now. Hysteria does not mean that the reaction is overblown or unjustified. (the non-medical definition of hysteria involves excessive OR uncontrollable fear, and it’s the second aspect I had in mind when saying “some” hysteria is justified) Sometimes, something really truly scary is happening, and this is my considered scientific judgement about the situation with global warming. As I’ve said before, I’m not alarmist — just plain alarmed. Now, if you are trying to get out of a dangerous situation, it’s far better to stay calm than to panic, so if hysteria can be avoided that’s all to the good. Same situation with global warming. If the situation gets so out of hand that people get forced into a panic reaction in 50 years, mistakes are going to be made. All in all, it would be best if the powers that be paid attention to the scientific arguments and acted accordingly. But, when something terrible is coming down the pike and absolutely nothing is being done to stop it, you can hardly blame those who do see it coming from feeling just a BIT hysterical, can you? –raypierre]

Ray doesn’t mention my modeling work also misrepresented by William Broad. I have been looking over the past 20 years at factors affecting the carbon cycle during the Phanerozoic. This is summarized in my book The Phanerozoic Carbon Cycle (Oxford University Press, 2004) There are very many factors affecting CO2 that are not obvious on a human or even Pleistocene time scale. This includes the feedback of global warming on CO2 uptake by increased silicate rock weathering and CO2-induced increased plant productivity as it also affects CO2 uptake by weathering. The rise of vascular land plants during the Paleozoic undoubtedly had a large effect on CO2 uptake via both increased weathering and the accumulation of carbonaceous debris in rocks. Continental drift affects both continental temperatures and river runoff and crude estimates of such factors has been made via GCM modeling The whole long term carbon cycle and its effect on CO2 should not be ignored and replaced by simplistic assumptions for quick calculations of paleo-CO2. Nevertheless, ten million year averages for the many (over 400) independent proxies fall within my estimated error margins, obtained via sensitivity analysis, which are VERY WIDE. A copy of this data is being sent to Ray personally. I couldn’t reproduce it here. Also,the two major extended periods of glaciation (Permo-Carboniferous) and the past 30 million years agree both with modeling and proxy averages. This is crude by modern modelling standards but it is strongly suggestive of a correlation of CO2 with climate. If you don’t like any of this, at least look at my book.

#17 Thanks Raypierre, I don’t have a book store or library here, so will make do with reading RC until I head South again.

As you have imagined, I am very intrigued by CO2 at all levels of the temperature profile. Equally interested with all greenhouse gases for that matter. If I understand you right, there are specific regions above us where

CO2 actually warms the atmosphere, while other

regions with CO2, still bombarded with LR’s not suitable for absorption. Is there

any particular height where absorption is maximized? And also minimized?

[Response: Regarding the book — until I actually finish the thing and send it to the publisher’s, draft in progress is available for free on the web. Go to http://geosci.uchicago.edu/~rtp1/ClimateBook/ClimateBook.html . Chapter 3 is where you want to look, plus the grey gas part of Chapter 4, if you’re up to it. –raypierre]

Re: criticism

For the critics of Broad, and the critics of the criticism, I offer Galileo’s advice: that one should give every author the benefit of the *best* possible interpretation of what has been written.

Galileo didn’t have the bandwidth to ask the author to provide the sources and cites and footnotes that didn’t fit on the original printed page, nor to ask the author’s sources whether they were represented correctly.

“Trust but verify.” — R. Reagan.

Rob Rohde has an interesting composite plot of published Phanerozoic CO2 estimates (unfortunately plotted backwards, as palaeo types are want to do). It gives a fair idea of the scatter issue.

BUT, where can we see all this data plotted with some parallel palaeotemperature estimates? Answer seems to be nowhere.

The last couple of decades have seen extraordinary progress in palaeoclimate reconstructions from multiple sources – particularly the ice cores, the ODP and the various Holocene proxies. Mostly real hard data (well, at least semi-hard), not crusty old geological inference. Despite what you say, I think this stuff is highly relevant to any overview of AGW projections, if only to set a context. It deserves to be collated and accessible. Odd, then, that we have to rely on one dedicated Californian PhD student to do the work. And even he is reluctant to cobble it all together (like this), for fear of the obvious criticisms. I hope the 4AR chapter will give us something more to work with…

[Response: One gets into trouble immediately when trying to figure out which “paleotemperature” to plot. It’s very difficult to get an estimate of the global mean temperature. Some proxies give land temperature, but the latitudes available change over time. For the more recent parts of the phanerozoic, one can get estimates of tropical and deep-ocean temperature separately. Dan Rothman’s paper has a crude comparison with his own CO2 reconstruction, where the climates are crudely categorized as “warm” or “cold”. I very highly recommend the paper by Royer, Berner, Montanez, Tabor and Beerling in GSA Today, which is one of the best works available on the issue of CO2 and temperature in deep time. While there are some times when the CO2 and temperature reconstructions are more problematic than at other times, it should particularly be noted in this paper that the association between cooling and a major CO2 drop holds not only for the past 50 million years but also the time around the Carboniferous. This is work I probably should have highlighted explicitly in my write-up, but I assumed it was well-known to our readership though our various discussions of Veizer and Shaviv, since it is one of the main texts rebutting their viewpoint. Required reading, as it were. It’s available to the public here . Bob Berner has pointed out to me that this article also raises serious questions about Rothman’s reconstruction of CO2. –raypierre]

Re 30.

Wayne, you may also want to check out https://www.realclimate.org/index.php?p=58. This has been covered somewhat before.

PS. Are you the same Wayne Davidson that is at the weather office at Resolute ? If so we have met before, I passed through there on my way to Eureka to make O3 measurements in the mid 90’s. We were also both at Eureka for a while in 96 (I think it was).

No. 29 states my original question in re the NYT article: how sure are we that we are not failing to factoring in extremely long-cycle effects, of which we are not aware? do the questions surrounding deep-time suggest the presence of these effects? could human induced changes in GHGs, deforestation, et cetera kick these effects into a higher gear?

[Response: It’s not so much the long cycle effects I’m worried about myself. What the puzzles of deep time climate make me worry about are the possibilities of destabilizing feedbacks that kick in in a higher CO2, warmer, world, that we don’t yet know about. One could legitimately raise the question of whether further study of the Phanerozoic will reveal stabilizing feedbacks instead (e.g. some kind of cloud fraction thermostat), but on the evidence so far I view that as unlikely. It’s hard enough to get the climate to change as much as it did, using the rather energy balance changes due to GHG, continental configurations, and equally well those potentially due to cosmic rays. With any major stabilizing feedback, explaining the Phanerozoic climate variations becomes just about impossible. –raypierre]

#34, What a surprise Dave! You must be in Europe? Can’t meet at a better place though.

Our yellow star overtook my attention I use to give to the red star. Working on something radical which was always in front of us.. Thanks for the link, GHG’s affect the mid troposphere it appears, quite interesting , reading Raypierre’s book will likely confirm. You would not be familiar with the temperatures here, compared to 96-97, which in my memory was the last cold winter. -45 to -50 C for extended periods, I am sure you have not forgot Halebop and other mysteries seen during the very long night.

#34, thanks for that Ray. I guess Royer et al illustrates my point. It’s the failure to do the obvious with the results, like this, that irks. There is a solid story there even using Veizer’s uncorrected interp. It just isn’t presented.

“One gets into trouble immediately when trying to figure out which paleotemperature to plot.” Well, yes – the first of those “obvious criticisms”. But hardly a sound reason to not try, when faced with a matter serious enough to warrant even some “hysteria”? Fact is, there seems to be pretty fair data suggesting that our world hasn’t been as hot as where we’re headed this century for about 15My. And CO2 probably hasn’t been as high as where we’re headed for maybe 20My. That’s seriously important information, even if uncertain and incomplete. It needs to be collated and presented, clearly…

Ray… I looked at the latest draft of the climate book. Very nice work, and I can’t wait for the missing portions to be filled in. I have some caveats, but they’re trivial, e.g., the bolometric Bond albedo of Venus is 0.76 (Taylor 1983), not 0.65, which is a way obsolete figure. You also give the mean global annual surface temperature of the Earth as 285 and 286 K, which is Sellers’s figure from 1965. All the modern estimates I’ve read in the literature have it as either 287 or 288 K (e.g. Henderson-Sellers’s book, Houghton’s, etc.)

“And then, too, the tired old beast of Galactic Cosmic Rays (GCR) raises its hoary head in Broad’s article”

The tone of this comment is odd considering the recent high quality scientific papers which examine how modulation of GCR, by the sun, and changes to the base level of GCR, which occur then the solar system periodically moves through the galactic plane, both affect the earth’s climate.

The GCR hypothesis appears to answer a number of fundamental unresolved puzzles in Paleoclimatology, such as the “100 kyr eccentricity problem” and other orbital forcing related problems, the “faint sun problem”, or the fact that the increase in CO2 levels lags the increase in temperature, at the cycle change from glacial to interglacial.

Shaviv and Veizer’s paper “Celestial driver of Phanerozic Climate?” is certainty not a rehash of an old tired hypothesis.

While I could not find a direct link to that paper, Shavis and Veizer’s response to Rahmstorte et al’s rebuttal of their paper “Celestial driver of Phanerozic Climate?” is a summary of the salient issues.

http://www.phys.huji.ac.il/~shaviv/ClimateDebate/RahmstorfDebate.pdf

From Shaviv and Veizer’s response.

“We show here why the various criticism raised are either irrelevant or erroneous. Thus the conclusions reached by Shaviv & Veizer (2003) are still valid. In particular, the dominate climate driver on the multi-million year time scale is the variable cosmic-ray flux. CO2 is important, but it likely plays a secondary role in determining the climate.”

“… we fully support the development of alternative energy sources, simply because of real pollution and resource conservation considerations,… ”

“Last, a periodicity in Cosmic Ray Flux (CRF) is predicted by the current astronomical theory. Summing up, we did not use only 20 meteorites to reconstruct the CRF. We used all K-dated meteroites (80 reduced to 50 “heterogenenous” ones) to obtain the most accurate signal possible …”

“The astronomical constraints alone do indicate that the CRF should have been variable, that the period should be 135 25+/- Ma, that the CRF should peak at 31 8+/-yr after the spiral arm passage, that the last passage was at about 50 Ma before present, that the CFR had amplitude variations between a factor of 2 to 10. Clearly they are not trival.”

“We are well aware of these complications, but the available publication space did not permit,… Further, we fail to see how this musing would change the statement that “it is not clear whether CO2 is a driver or is being driven by climate change since the CO2 appears to lag by centuries behind the temperature changes, potentially acting as an amplifier but not as a driver”.

“It remains to be seen whether orbital forcing is the primary driver, since the evidence for correlations with cosmogenic nuclides is accumulating, Sharma, (2002); Christl et al. (2003); Niggermann et al. (2003).

The following is another paper by Shiva “Cosmic Rays and Climate Sensitivity” which I also found interesting.

http://arxiv.org/pdf/physics/0409123

[Response: The cosmic ray theory isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, especially with regard to its implications for modern day climate sensitivity. This has been extensively discussed in various earlier RealClimate posts, some of which I linked in the article. –raypierre]

[Response: Here are a few further thoughts concerning your comments on the cosmic ray theory. First, it is not enough to just quote-mine from Veizer’s response and miscellaneous papers. Just about every criticism of a published paper gets some kind of response. The fact that there’s a response doesn’t mean it’s a valid rebuttal. You have to look at the actual arguments. The criticisms of the suggested implication for recent climate, and Berner’s criticisms of the lack of a pH correction in the reconstruction of earlier Phanerozoic CO2, are compelling. Also, one must recall that when it comes to the effect of CO2 on climate we are not working in a vacuum. There are certain things we know about the effect of CO2 on climate that come from basic established physics; we are not trying to reason entirely from the emipirical record of past climate. The work of the GCR proponents (particularly Veizer) ignores this in trying to shoehorn the whole past into their concept. I wish to make clear that there are hierarchies of ridiculousness, though: the idea that cosmic rays rather than CO2 are mostly responsible for recent climate changes are absolutely ridiculous and should just disappear from the discussion, while the idea that cosmic rays might have played some partial role in earlier climate change is questionable but hard to discount completely, given what we don’t know about clouds. The latter deserves further study, but the people doing it have to start trusting the basic physics more if they are going to make progress.

This all raises another question, on the journalistic side, regarding the “false balance” issue. Broad clearly should have known better regarding the inappropriate implication that the cosmic ray theory might have some implications for anthropogenic global warming, but it’s somewhat harder to blame him for not getting an accurate read of the scientific community’s assessment of CO2 and Phanerozoic climate. After all, even with the weight of the IPCC, it took a long time for reporters to really understand what the consensus is regarding global warming. There hasn’t been any analogous consensus document on Phanerozoic climate, and I’d hate to see science go in a direction where such things should be needed for all outstanding problems. Those of us in the trenches of science know that Berner is a towering figure in the field with a reputation for very meticulous work, that Rothman is brilliant but a relative newcomer to geochemistry (using a largely untried CO2 and somewhat speculative reconstruction technique), that Veizer’s work is very problematic. To a reporter, looking at a small field where a single vocal figure on the fringe (like Veizer) can make so much noise so repetitively that he wears out the patients of those who need to refute endless permutations of the same wrong arguments, I can see how it can be hard to get a read on who’s who, and who to listen to. William Broad was wrong to put Veizer’s arguments on the same plane as others, but how was he to know he was wrong? How does a science writer know when balance crosses over into false balance? Of course the ideal thing is for the reporter to actually deeply understand the science, but that may be a bit much to ask for, given the amount of territory reporters need to cover. We aim to help out with this on RealClimate, but I can understand a reporters’ being reluctant to lean too much on one blog as a source. It’s a sticky problem, and I’d like to hear what both readers and science writers think about this. –raypierre]

Raypierre :

Even in Rothman’s reconstruction, during the past 50 milllion years — when the data is best and continents are most like the present — the long term cooling trend leading into the Pleistocene is clearly associated with a long term CO2 decline. This is not our main reason to infer that increasing CO2 will warm the climate in the future, but insofar as the data supports CO2 decline as a main culprit in the long slide from the Cretaceous hothouse climates of 60 million years ago to the cold Pleistocene climate, it also lends weight to the notion that as industrial activity busily restores CO2 to levels approaching those of the Cretaceous, climate is likely to turn the climate clock back 60 million years as well.

How do you jump from “associated with” to “main culprit” ? Correlations are note causations and CO2 trends as well as temperature trends from 50 My BP to Holocene could be (at least partially) the effects of other cause(s). A minima, to define CO2 as the main responsible for T variations of Pleistocene suppose that we know all the forcings, all their sensitivities and so quantify their relative weight. Do we ?

[Response: That’s “supports” as in “is consistent with.” I’m only addressing the claim that the CO2/climate record is patently inconsistent with CO2 being a dominant control. But as for additional evidence of the cause of the cooling trend, there’s the fact that one can get close to this magnitude of cooling with standard models of climate sensitivity to CO2, and so far there isn’t any viable competing theory. The GCR idea isn’t even close to being quantified well enough to be tested. In that sense, as a theory “it’s not even wrong.” –raypierre]

My own comment to Broad – timescales, specifically making comparisons twixt distant long and recent short – has been I suspect covered earlier by yr previous commenter/s.

And yes, words-in-the-way viz “blocking” did irritate some, but at first reading your post I was left wondering well, why try take down Wm. Broad who, as far as I know, attempts pitch his stories on actual things, events, disputes etc. As opposed, say, an earlier mistake at the Times with Tierney’s talking points denialist diatribe.?

Not to defend y’understand though likely true to some extent, I’d like to point out that journalism’s publications have their styles. And one thing I find highly pertinent at the NYT is that that considered readerships’ weight is given toward the end of a piece. My own take on this is that prior to this weighted content there is need to draw readership in. Need to be, albeit sedately, provocative. Need to get over, as it were, those holding the accepted science on global warming pov. In order to reach its opponents.. debate arising on and, as I said, real dispute/s. Hopefully widening. Informing..?

The matter of publication date: 7th November. Election day. A let’s get serious day. Tone, in journalism, still exists. Thankfully.

Given the time I could expand on these things, but that’s not the point of RealClimate’s excellent blog and services to interested folks..

best..

[Response: Nobody’s trying to “take down” Broad. The point is to discuss what’s wrong with the thrust of the article, so Broad and other science writers can do better with this class of issues next time. The point is also to put some more valid information out on the blogosphere, so some of the (probably inadvertent) damage that might be caused by Broad’s article can be averted. I wouldn’t have written a post based on the lesser quibbles I pointed out; the main problem was Broad’s conflation of the general mysteries of Phanerozoic climate with the issue of near-term climate sensitivity. As long as I was writing the article, though, I thought it was worth pointing out the lesser matters as well. –raypierre]

Re #35 response: Ray, I had thought that the recovery from the PETM was evidence of some such stabilizing feedback. Is that not right?

[Response: Yes, but it’s a stabilizing feedback we know well — silicate weathering — and takes about 100,000 years to operate. It’s not going to save us from global warming. –raypierre]

Biological feedback is — as Dr. Lovelock would remind us — stabilizing, over the long geological term.

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 241 (2006) 361�371

Paleoceanographic changes across the Jurassic/Cretaceous boundary:

The calcareous phytoplankton response

Fabrizio Tremolada et al.

http://www.geosc.psu.edu/people/faculty/personalpages/tbralower/Tremolada_et_al_06_epsl.pdf.

Raypierre, you said: “What the puzzles of deep time climate make me *worry* about are the possibilities of destabilizing feedbacks that kick in a higher CO2, warmer, world, that we don’t yet know about”

What if I said? “What the puzzles of deep time climate make me *curious* about are the possibilities of negative feedbacks causing a cooler world than we might anticipate from simply the radiative forcing of CO2 alone, that we don’t yet know about”

Why do you have license to envoke the “puzzles of deep time climate” to “worry” about a possible catastrophe, but I am chastened for envoking the same “puzzles of deep time climate” to support my “curiosity” about why this catastrophe may not occur? It might appear to some that your statement betrays an “advocacy position”, instead of one of pure scientific endevour. Then again, so might mine.

It is healthy that reporters do not come soley to RC for their information, because at times, the viewpoint expressed here is too narrow.

[Response: I’m not just worrying here idly. The uncertainties in what is going on in the Phanerozoic if anything are specifically suggestive of destabilizing mechanisms we don’t know about. CO2 is the only thing we know that moves temperature around enough to come close to explaining the Phan. but it doesn’t move the polar temperatures around enough. Mayber there’s something else, but so far as quantified physics goes, CO2 and a few other GHG’s are the only game in town. So, there I’ve ponied up my physics. Now you have to pony up yours or fold and quit. Another way of thinking about it is this: What are the consequences if my “worry” is right, vs the conseqences if your “curiosity” is wrong? –raypierre]

The URL directing folks to my commentary on Bill Broad’s piece and broader issues on the Center for Science and Technology Policy weblog is broken. If you’re interested to hear another science and environemtnal reporter’s perspective, go to: http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/, and click on the “Prometheus” link at the top right corner of the page.

And by the way, perhaps it is self-serving to say this, but why do you suppose that 68 percent of Americans polled in a recent Pew survey said the federal government should take “immediate action” on climate change? I don’t think Americans arrived at that conclusion by reading Science, Nature, JGR, etc. The vast majority of Americans get their news about issues like climate change from news media. I suppose if you doubt whether climate change deserves immediate action, you might count this as evidence for shoddy coverage of the issue by news media. But I suspect that most readers and contributors to this blog are not in that camp. So if science and environmental reporters have gotten things so very, very badly, as several posts in this thread seem to suggest, then how do you explain the fact that more than two thirds of Americans take climate change seriously, and not only that but believe it is an urgent enough problem to warrant immediate action?

Tom Yulsman

Co-director, Center for Environmental Journalism

University of Colorado at Boulder

[Response: Fixed the link. Sorry about that. – gavin]

[Response: I hope people don’t come away with the impression that we think most science writing is junk. Up until recently, there did indeed seem to be one nearly ubiquitous problem with writing on global warming, which was the “false objectivity of balance” issue. This has largely subsided in recent times, but even that should not have been taken as a blanket indictment of science writing. In the last few years, there has been a marked change in the forcefulness of journalism related to global warming, and I’d like to think that this is part of the change in public perception on the urgency of the issue. However, like most academics, I live in a bubble and my ideas of where people get their opinions are probably not worth much. I’m a real newspaper addict myself, but given what a small fraction of the population reads the major newspapers, it’s not clear how much leverage even the best science writing there has. Maybe it has a disproportionate influence because it reaches a high proportion of “opinion makers.” Perhaps most people are getting their ideas from television. I’d really like to know the source of information on which people are basing opinions such as those in the poll numbers you mention above.

By looking at the gap between the magnitude of action and the magnitude of the problem, though, I have a suspicion that the poll numbers represent concern, but not deep enough concern for people to demand the kind of major actions that would be needed even to keep CO2 from going beyond doubling. Even among people who express concern, I only see the things happening that don’t require any hard decisions. Some people are giving up SUV’s for more efficient cars, but it’s far from common. People still aren’t clamoring for carbon taxes on coal, which are probably the only way to make IGCC and sequestration the coal technology of choice, and put renewables on a level playing field. Maybe the actions planned in California are the beginning of a groundswell of action, but I don’t see yet that people have put the War on Global Warming in the same category as the effort that mobilized the nation to win WWII. It’s really that big, maybe bigger. -raypierre]

Raypierre, Gavin et. al.,

re. #4 (Global warming caused mass-extinctions?)

Can you please do a post on this global warming causing H2S mass extinctions theory in terms of its validity? It is also in the Journals of Science, Nature, Geology, and Geotimes to name a few, so you can’t be accused of being “alarmist”.

A good geochemist could write a good post on it.

Thanks,

Richard

Re: #45

Al Gore.

Re: #44 Raypierre, you say: “CO2 and a few other GHG’s are the only game in town” and “so, there I’ve ponied up my physics. Now you have to pony up yours or fold and quit”.

The entire class of aerosols and aerosol indirect effects are another good game in town we might want to buy a ticket to see. How about changes in albedo due to things like dark-colored soot or volcanic ash covering the poles? How much do we really know about dust? The latter variables might be the minor leagues, but also interesting. How about evolution of landforms and vegetation affecting earth’s albedo across deep time? How about changes in landuse and associated teleconnections across not so deep time?

There is plenty of good physics to go around. I do not think I will fold just yet.

[Response: You haven’t even made a start. You’ve got to tell me how these sorts of things are supposed to have accounted for the various changes across the Phanerozoic. I can tell you how CO2 causes warming and how much, and what factors tend to cause it to change. You’re going to have trouble getting soot from forest fires before land plants had evolved. It’s one thing to parrot a laundry list of vague possibilities. It’s another to get serious about how to assess them. Note, too, that even if we knew nothing about earlier Phanerozoic climate there’s plenty of cause in basic verifiable physics and the recent climate observations vs. theory to tell us that CO2 is almost certain to cause substantial future warming. The additional sources of worry I find in the Phanerozoic puzzles are just icing on the cake, as it were. If I may paraphrase your stance, it’s “Let’s just burn all the coal and pray for a miracle.” –raypierre]

The problem with almost all alarmist speculations or non-alarmist speculations is we really have no basis to analyze the problem. We can point to various parallels in the past – mass extinctions, Medieval Warm Period, Little Ice Age – but, as they say in the investment prospectus, “past performance does not guarantee future results”.

The non-alarmists always have the odds on their side. Big shifts and changes in climate are rare. So the alarmists should have to meet a much higher standard to prove their point.

[Response: Balderdash. We have over 150 years of basic physics, going back to Fourier 1827, to go on. And as for direct proofs that climate is sensitive to CO2, the southern hemisphere cooling during the Last Glacial Maximum is about as direct as they come. No ice age in the SH without sensitivity to CO2. –raypierre]

#49 “Big shifts and changes in climate are rare. So the alarmists should have to meet a much higher standard to prove their point.”

Really? Looks to me like big shifts are pretty common, albeit in the opposite direction. And that’s not just common on geological timescales. When I engineer a large dam – one that might kill thousands if it fails – I’m obliged by internation design guidelines to consider events with annual probabilities in the order of 1 in 10^5 to 1 in 10^6. Because the consequences of failure are large. How big are the consequences of here?