by Stefan Rahmstorf, Michael Mann, Rasmus Benestad, Gavin Schmidt, and William Connolley

On Monday August 29, Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans, Louisiana and Missisippi, leaving a trail of destruction in her wake. It will be some time until the full toll of this hurricane can be assessed, but the devastating human and environmental impacts are already obvious.

Katrina was the most feared of all meteorological events, a major hurricane making landfall in a highly-populated low-lying region. In the wake of this devastation, many have questioned whether global warming may have contributed to this disaster. Could New Orleans be the first major U.S. city ravaged by human-caused climate change?

[lang_fr]

by Stefan Rahmstorf, Michael Mann, Rasmus Benestad, Gavin Schmidt, and William Connolley (traduit par Claire Rollion Bard)

Le lundi 29 août, l’ouragan Katrina a ravagé la Nouvelle-Orléans, la Louisiane et le Mississipi, laissant une traînée de destruction dans son sillage. Il va se passer du temps avant que le bilan total de cet ouragan soit estimé, mais les impacts environnementaux et humains sont déjà apparents.

Katrina était le plus craint des évènements météorologiques, un ouragan majeur laissant un terrain vide dans une région très peuplée de faible élévation. Dans le sillage de sa dévastation, beaucoup se sont demandés si le réchauffement global pouvait avoir contribué à ce désastre. La Nouvelle-Orléans pourrait-elle être la première ville majeure des Etats-Unis à être ravagée par le changement climatique causé par les humains ?

(suite…)

[\lang_fr]

[lang_es]Traducción disponible aqui (gracias a Mario Cuellar).[/lang_es]

The correct answer–the one we have indeed provided in previous posts (Storms & Global Warming II, Some recent updates and Storms and Climate Change) –is that there is no way to prove that Katrina either was, or was not, affected by global warming. For a single event, regardless of how extreme, such attribution is fundamentally impossible. We only have one Earth, and it will follow only one of an infinite number of possible weather sequences. It is impossible to know whether or not this event would have taken place if we had not increased the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere as much as we have. Weather events will always result from a combination of deterministic factors (including greenhouse gas forcing or slow natural climate cycles) and stochastic factors (pure chance).

Due to this semi-random nature of weather, it is wrong to blame any one event such as Katrina specifically on global warming – and of course it is just as indefensible to blame Katrina on a long-term natural cycle in the climate.

Yet this is not the right way to frame the question. As we have also pointed out in previous posts, we can indeed draw some important conclusions about the links between hurricane activity and global warming in a statistical sense. The situation is analogous to rolling loaded dice: one could, if one was so inclined, construct a set of dice where sixes occur twice as often as normal. But if you were to roll a six using these dice, you could not blame it specifically on the fact that the dice had been loaded. Half of the sixes would have occurred anyway, even with normal dice. Loading the dice simply doubled the odds. In the same manner, while we cannot draw firm conclusions about one single hurricane, we can draw some conclusions about hurricanes more generally. In particular, the available scientific evidence indicates that it is likely that global warming will make – and possibly already is making – those hurricanes that form more destructive than they otherwise would have been.

The key connection is that between sea surface temperatures (we abbreviate this as SST) and the power of hurricanes. Without going into technical details about the dynamics and thermodynamics involved in tropical storms and hurricanes (an excellent discussion of this can be found here), the basic connection between the two is actually fairly simple: warm water, and the instability in the lower atmosphere that is created by it, is the energy source of hurricanes. This is why they only arise in the tropics and during the season when SSTs are highest (June to November in the tropical North Atlantic).

SST is not the only influence on hurricane formation. Strong shear in atmospheric winds (that is, changes in wind strength and direction with height in the atmosphere above the surface), for example, inhibits development of the highly organized structure that is required for a hurricane to form. In the case of Atlantic hurricanes, the El Nino/Southern Oscillation tends to influence the vertical wind shear, and thus, in turn, the number of hurricanes that tend to form in a given year. Many other features of the process of hurricane development and strengthening, however, are closely linked to SST.

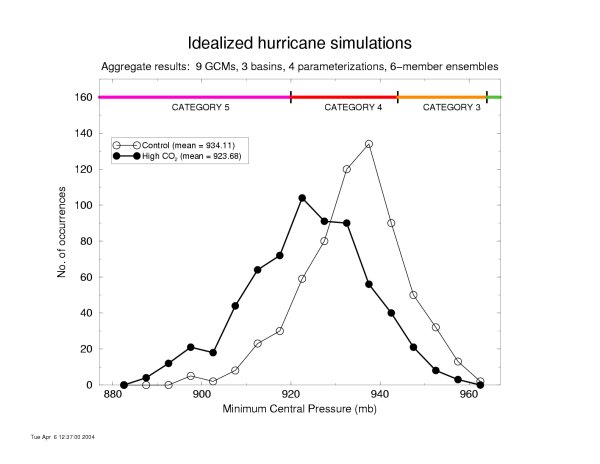

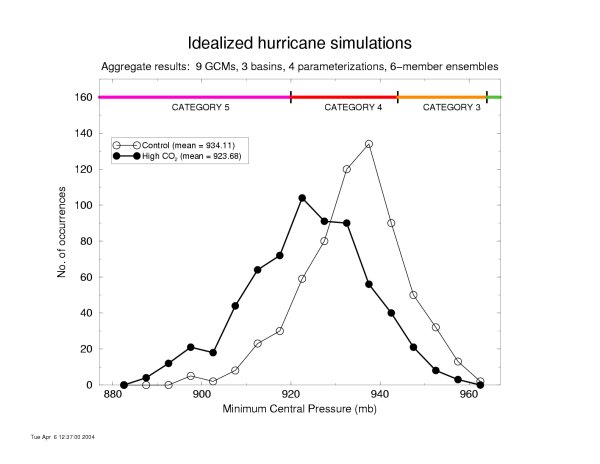

Hurricane forecast models (the same ones that were used to predict Katrina’s path) indicate a tendency for more intense (but not overall more frequent) hurricanes when they are run for climate change scenarios (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Model Simulation of Trend in Hurricanes (from Knutson et al, 2004)

In the particular simulation shown above, the frequency of the strongest (category 5) hurricanes roughly triples in the anthropogenic climate change scenario relative to the control. This suggests that hurricanes may indeed become more destructive (1) as tropical SSTs warm due to anthropogenic impacts.

But what about the past? What do the observations of the last century actually show? Some past studies (e.g. Goldenberg et al, 2001) assert that there is no evidence of any long-term increase in statistical measures of tropical Atlantic hurricane activity, despite the ongoing global warming. These studies, however, have focused on the frequency of all tropical storms and hurricanes (lumping the weak ones in with the strong ones) rather than a measure of changes in the intensity of the storms. As we have discussed elsewhere on this site, statistical measures that focus on trends in the strongest category storms, maximum hurricane winds, and changes in minimum central pressures, suggest a systematic increase in the intensities of those storms that form. This finding is consistent with the model simulations.

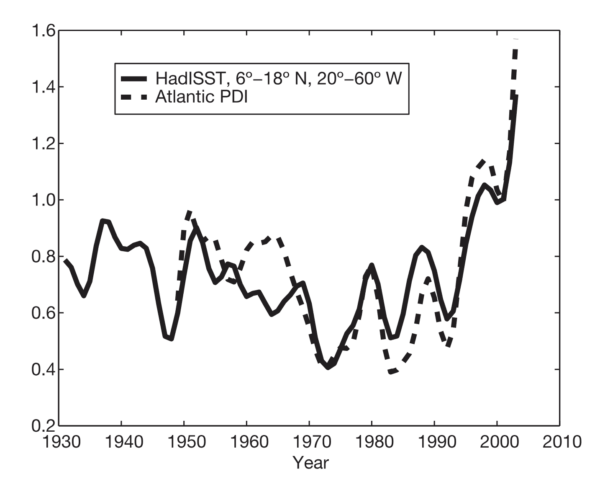

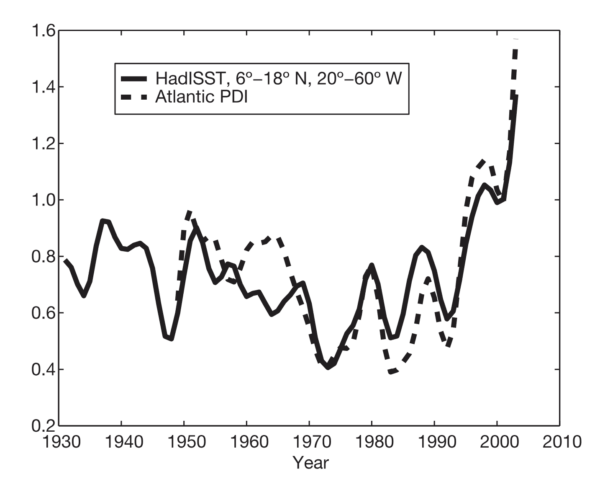

A recent study in Nature by Emanuel (2005) examined, for the first time, a statistical measure of the power dissipation associated with past hurricane activity (i.e., the “Power Dissipation Index” or “PDI”–Fig. 2). Emanuel found a close correlation between increases in this measure of hurricane activity (which is likely a better measure of the destructive potential of the storms than previously used measures) and rising tropical North Atlantic SST, consistent with basic theoretical expectations. As tropical SSTs have increased in past decades, so has the intrinsic destructive potential of hurricanes.

Figure 2. Measure of total power dissipated annually by tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic (the power dissipation index “PDI”) compared to September tropical North Atlantic SST (from Emanuel, 2005)

The key question then becomes this: Why has SST increased in the tropics? Is this increase due to global warming (which is almost certainly in large part due to human impacts on climate)? Or is this increase part of a natural cycle?

It has been asserted (for example, by the NOAA National Hurricane Center) that the recent upturn in hurricane activity is due to a natural cycle, e.g. the so-called Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (“AMO”). The new results by Emanuel (Fig. 2) argue against this hypothesis being the sole explanation: the recent increase in SST (at least for September as shown in the Figure) is well outside the range of any past oscillations. Emanuel therefore concludes in his paper that “the large upswing in the last decade is unprecedented, and probably reflects the effect of global warming.” However, caution is always warranted with very new scientific results until they have been thoroughly discussed by the community and either supported or challenged by further analyses. Previous analysis of the AMO and natural oscillation modes in the Atlantic (Delworth and Mann, 2000; Kerr, 2000) suggest that the amplitude of natural SST variations averaged over the tropics is about 0.1-0.2 ºC, so a swing from the coldest to warmest phase could explain up to ~0.4 ºC warming.

What about the alternative hypothesis: the contribution of anthropogenic greenhouse gases to tropical SST warming? How strong do we expect this to be? One way to estimate this is to use climate models. Driven by anthropogenic forcings, these show a warming of tropical SST in the Atlantic of about 0.2 – 0.5 ºC. Globally, SST has increased by ~0.6 ºC in the past hundred years. This mostly reflects the response to global radiative forcings, which are dominated by anthropogenic forcing over the 20th Century. Regional modes of variability, such as the AMO, largely cancel out and make a very small contribution in the global mean SST changes.

Thus, we can conclude that both a natural cycle (the AMO) and anthropogenic forcing could have made roughly equally large contributions to the warming of the tropical Atlantic over the past decades, with an exact attribution impossible so far. The observed warming is likely the result of a combined effect: data strongly suggest that the AMO has been in a warming phase for the past two or three decades, and we also know that at the same time anthropogenic global warming is ongoing.

Finally, then, we come back to Katrina. This storm was a weak (category 1) hurricane when crossing Florida, and only gained force later over the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico. So the question to ask here is: why is the Gulf of Mexico so hot at present – how much of this could be attributed to global warming, and how much to natural variability? More detailed analysis of the SST changes in the relevant regions, and comparisons with model predictions, will probably shed more light on this question in the future. At present, however, the available scientific evidence suggests that it would be premature to assert that the recent anomalous behavior can be attributed entirely to a natural cycle.

But ultimately the answer to what caused Katrina is of little practical value. Katrina is in the past. Far more important is learning something for the future, as this could help reduce the risk of further tragedies. Better protection against hurricanes will be an obvious discussion point over the coming months, to which as climatologists we are not particularly qualified to contribute. But climate science can help us understand how human actions influence climate. The current evidence strongly suggests that:

(a) hurricanes tend to become more destructive as ocean temperatures rise, and

(b) an unchecked rise in greenhouse gas concentrations will very likely increase ocean temperatures further, ultimately overwhelming any natural oscillations.

Scenarios for future global warming show tropical SST rising by a few degrees, not just tenths of a degree (see e.g. results from the Hadley Centre model and the implications for hurricanes shown in Fig. 1 above). That is the important message from science. What we need to discuss is not what caused Katrina, but the likelyhood that global warming will make hurricanes even worse in future.

_____________________

1. By ‘destructive’ we refer only to the intrinsic ability of the storm to do damage to its environment due to its strength. The potential increases that we discuss apply only to this intrinsic meteorological measure. We are not taking into account the potential for increased destruction (and cost) due to increasing population or human infrastructure.

References:

Delworth, T.L., Mann, M.E., Observed and Simulated Multidecadal Variability in the Northern Hemisphere, Climate Dynamics, 16, 661-676, 2000.

Emanuel, K. (2005), Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years, Nature, online publication; published online 31 July 2005 | doi: 10.1038/nature03906

Goldenberg, S.B., C.W. Landsea, A.M. Mestas-Nuñez, and W.M. Gray. The recent increase in Atlantic hurricane activity. Causes and implications. Science, 293:474-479 (2001).

Kerr, R.A., 2000, A North Atlantic climate pacemaker for the centuries: Science, v. 288, p. 1984-1986.

Knutson, T. K., and R. E. Tuleya, 2004: Impact of CO2-induced warming on simulated hurricane intensity and precipitation: Sensitivity to the choice of climate model and convective parameterization. Journal of Climate, 17(18), 3477-3495.

[lang_fr]

La réponse correcte — celle que nous avons fournie dans les articles précédents (Storms & Global Warming II, Some recent updates and Storms and climate change) — est qu’il n’y a aucune manière de prouver que Katrina était ou n’était pas affectée par le réchauffement global. Pour un seul événement, sans regarder à quel point il est extrême, une telle attribution est fondamentalement impossible. Nous avons seulement une Terre et elle suivra seulement une des infinies possibilités de séquence du temps. Il est impossible de savoir si cet événement aurait eu lieu ou pas si nous n’avions pas eu d’augmentation de la concentration de gaz à effet de serre dans l’atmosphère autant que nous avons. Les évènements du temps résultent toujours d’une combinaison de facteurs déterminants (incluant le forçage des gaz à effet de serre ou les cycles lents naturels du climat) et de facteurs stochastiques (pure chance).

Dû au semi-hasard de la nature du temps, nous avons tort d’imputer un seul événement tel que Katrina au réchauffement global – et, bien sûr, il est juste indéfendable de blâmer Katrina d’un cycle naturel à long terme dans le climat.

Néanmoins, ce n’est pas la bonne manière d’encadrer la question. Comme nous l’avons indiqué dans des articles précédents, nous pouvons en effet dessiner quelques conclusions importantes sur les liens entre l’activité des ouragans et le réchauffement global dans un sens statistique. La situation est analogue à faire rouler un dé pipé : on peut, si on a l’envie, construire un ensemble de dés où les 6 sortent deux fois plus souvent que la normale. Mais si on voulait tirer un six avec ces dés, on ne pourrait pas les blâmer spécifiquement sur le fait que les dés ont été pipés. La moitié des 6 seront tirés de toute façon, même avec un dé normal. Charger les dés a doublé simplement les impairs. De la même manière, bien que nous ne puissions pas tirer des conclusions fermes sur un seul ouragan, on peut tirer certaines conclusions sur des ouragans plus généralement. En particulier, la documentation scientifique à disposition indique qu’il est possible que le réchauffement global fera – et l’a peut-être déjà fait – que ces ouragans ont une forme plus destructive qu’ils auraient eu sinon.

Le lien clé est celui entre les températures des eaux de la mer de surface (abréviation TES – SST en anglais) et la puissance des ouragans. Sans aller trop loin dans les détails techniques sur la dynamique et la thermodynamique impliquées dans les tempêtes tropicales et les ouragans ( une excellent discussion de cela peut être trouvée ici), le lien fondamental entre les deux est assez simple : l’eau chaude, et l’instabilité dans la basse atmosphère que cela crée, est la source d’énergie des ouragans. C’est pourquoi ils surviennent seulement dans les tropiques et durant la saison où les TESs sont les plus élevées (Juin à Novembre dans l’Atlantique Nord tropical).

La TES n’est pas la seule influence sur la formation des ouragans. Un fort cisaillement dans les vents atmosphériques (c’est-à-dire, des changements dans la force du vent et la direction avec la hauteur d’atmosphère au-dessus de la surface), par exemple limite le développement de la structure hautement organisée qui est requise pour la formation d’un ouragan. Dans le cas des ouragans de l’Atlantique, l’ El Niño/Oscillation Australe a tendance à influencer le cisaillement vertical du vent et ainsi, en retour, le nombre d’ouragans qui se forment en une année donnée. Beaucoup d’autres caractéristiques du processus du développement des ouragans et leur force sont, cependant, étroitement liées à la TES.

Les modèles de prévision météorologique des ouragans (les mêmes qui ont été utilisés pour prédire le passage de Katrina) indiquent une tendance pour des ouragans plus intenses (mais, dans l’ensemble, pas plus fréquents) quand ils simulent pour des scénarii de changement climatique (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Simulation d’un modèle de tendance pour les ouragans (d’après Knutson et al., 2004)

Dans la simulation particulière montrée ci-dessus, la fréquence des ouragans les plus forts (catégorie 5) triplent grosso modo dans un scénario de changement anthropique du climat. Cela suggère que les ouragans pourraient, en effet, devenir plus destructifs (1) puisque les TESs tropicales se réchauffent à cause des impacts anthropiques.

Mais qu’en est-il du passé ? Que montrent vraiment les observations du dernier siècle ? Certaines études du passé (par exemple, Goldenberg et al., 2001) soutiennent qu’il n’y a aucune évidence d’une augmentation à long terme dans les mesures statistiques de l’activité des ouragans de l’Atlantique tropical, malgré le réchauffement global en cours. Ces études cependant se sont focalisées sur la fréquence de tous les ouragans et tempêtes tropicaux (réunissant les faibles et les forts) plutôt que de mesurer des changements dans l’intensité des tempêtes. Comme nous l’avons discuté auparavant sur ce site, les mesures statistiques qui se focalisent sur des tendances dans les tempêtes de catégorie la pus forte, le maximum des vents des ouragans, et des changements dans le minimum des pressions centrales, suggèrent une augmentation systématique dans les intensités des tempêtes qui se forment. Cette conclusion est cohérente avec les simulations des modèles.

Une étude récente dans Nature par Emanuel (2005) a examiné, pour la première fois, une mesure statistique de la dissipation de la puissance associée à l’activité des ouragans passés (i.e. “Indice de Dissipation de la Puissance” ou “IDP” — Fig. 2). Emanuel a trouvé une étroite relation entre l’augmentation dans la mesure de l’activité de l’ouragan (qui est susceptible d’être une meilleure mesure du potentiel destructif des tempêtes que les mesures précédemment utilisées) et la hausse de la TES de l’Atlantique Nord tropical, ce qui est cohérent avec les attentes théoriques. Comme les TESs tropicales ont augmenté durant les dernières décennies, alors le potentiel destructif intrinsèque des ouragans l’a fait aussi.

Figure 2. Mesure de la puissance totale dissipée annuellement par les cyclones tropicaux (Indice de Dissipation de Puissance “IDP”) comparée à la TES de Septembre de l’Atlantique Nord tropical (d’après Emanuel, 2005)

La question clé devient alors : pourquoi la TES a t-elle augmenté dans les tropiques ? Est-ce que cette augmentation est due au réchauffement global (qui est presque certainement en grande partie dû à l’impact humain sur le climat) ? Ou est-ce que cette augmentation fait partie d’un cycle naturel ?

Il a été affirmé (par exemple, par le NOAA National Hurricane Center) que la récente reprise dans l’activité des ouragans est due à une cycle naturel, nommé Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (“AMO”). Les nouveaux résultats d’Emanuel (Fig. 2) argumentent contre cette hypothèse comme seule explication : l’augmentation récente de la TES (au moins pour Septembre comme montré dans la figure) est bien en dehors de la gamme des oscillations passées. Emanuel conclut donc dans cet article que “la large hausse dans la dernière décennie est sans précédent, et probablement reflète l’effet du réchauffement global”. Cependant, la prudence est toujours de mise avec des résultats scientifiques très nouveaux jusqu’à ce qu’ils aient été complètement discutés par la communauté et soit supportés, soit affaiblis par des analyses supplémentaires. Des analyses précédentes du AMO et des modes d’oscillations naturelles dans l’Atlantique (Delworth and Mann, 2000 ; Kerr, 2000) suggèrent que l’amplitude des variations naturelles de la SST moyennée sur les tropiques est d’environ 0,1 – 0,2 °C, donc un basculement de la phase la plus froide à la phase la plus chaude peut expliquer jusqu’à 0,4 °C de réchauffement.

Qu’en est-il de l’hypothèse alternative : la contribution des gaz à effet de serre anthropiques au réchauffement de la TES tropicale ? A quelle force s’attend-on ? Une manière d’estimer cela est d’utiliser des modèles climatiques. Diriger par des forçages anthropiques, cela montre un réchauffement de la TES tropicale dans l’Atlantique d’environ 0,2 – 0,5 °C. Globalement, la TES a augmenté d’environ 0,6 °C dans les derniers 100 ans. Cela reflète principalement la réponse à des forçages radiatifs globaux qui sont dominés par le forçage anthropique au cours du XXe siècle. Les modes régionaux de variabilité, comme l’AMO, se neutralisent largement et font une faible contribution dans les changements globaux de TES moyenne.

Ainsi, nous pouvons conclure qu’à la fois un cycle naturel (l’AMO) et le forçage anthropique pourrait avoir fait grosso modo également de larges contributions au réchauffement de l’Atlantique tropical au cours des dernières décennies, avec une attribution exacte impossible jusqu’ici. Le réchauffement observé est probablement le résultat d’un effet combiné : des données suggèrent fortement que l’AMO a été dans une phase de réchauffement pour les deux ou trois dernières décennies, et nous savons aussi qu’au même moment le réchauffement anthropique global est en cours.

Alors, finalement, nous retournons à Katrina. Cette tempête était un faible ouragan (catégorie 1) quand elle a croisé la Floride, et a gagné de la force plus tard au-dessus des eaux chaudes du Golfe du Mexique. La question a posé alors ici est : pourquoi le Golfe du Mexique est si chaud actuellement – combien de cela peut être attribué au réchauffement global et combien à la variabilité naturelle ? Des analyses plus détaillées des changements de la TES dans les régions en question, et des comparaisons avec les prédictions des modèles, apporteront probablement de la lumière sur cette question dans l’avenir. À présent, cependant, la documentation scientifique disponible suggère qu’il serait prématuré d’affirmer que le récent comportement anormal peut être attribué entièrement à un cycle naturel.

Mais, en fin de compte, la réponse à ce qui a causé Katrina est d’une valeur pratique faible. Katrina est dans le passé. Beaucoup plus important est d’apprendre quelque chose pour le futur, puisque cela pourrait nous aider à réduire le risque de tragédies supplémentaires. Une meilleure protection contre les ouragans sera un point de discussion évident dans les mois à venir, auquel, en tant que climatologues, nous ne sommes pas particulièrement qualifiés pour contribuer. Mais la science du climat peut nous aider à comprendre comment les actions humaines influencent le climat. La documentation actuelle suggère fortement que :

(a) les ouragans ont tendance à devenir plus destructifs quand les températures de l’océan augmentent, et

(b) une hausse incontrôlée dans les concentrations des gaz à effet de serre sera fortement susceptible d’augmenter plus les températures de l’océan, surpassant en fin de compte toutes oscillations naturelles.

Les scénarii pour un réchauffement global futur montrent une TES tropicale augmentant de quelques degrés, pas juste des dixièmes de degré (voir par exemple, résultats du modèle du Hadley Centre et les implications montrées pour les ouragans fig. 1). C’est le message important de la science. Ce dont nous avons besoin de discuter n’est pas ce qui a causé Katrina, mais la probabilité qu’un réchauffement climatique fera des ouragans même pires dans le futur.

1. Par “destructif” nous nous référons à la capacité intrinsèque des tempêtes de faire des dommages à l’environnement à cause de sa force. L’augmentation potentielle dont nous discutons s’applique seulement à cette mesure météorologique intrinsèque. Nous ne prenons pas en compte le potentiel pour une destruction accrue (et un coût) due à une population en hausse ou à l’infrastructure humaine.

Références :

Delworth, T.L., Mann, M.E., Observed and Simulated Multidecadal Variability in the Northern Hemisphere, Climate Dynamics, 16, 661-676, 2000.

Emanuel, K. (2005), Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years, Nature, online publication; published online 31 July 2005 | doi: 10.1038/nature03906

Goldenberg, S.B., C.W. Landsea, A.M. Mestas-Nuñez, and W.M. Gray. The recent increase in Atlantic hurricane activity. Causes and implications. Science, 293:474-479 (2001).

Kerr, R.A., 2000, A North Atlantic climate pacemaker for the centuries: Science, v. 288, p. 1984-1986.

Knutson, T.K., and R.E. Tuleya, 2004: Impact of CO2-induced warming on simulated hurricane intensity and precipitation: Sensitivity to the choice of the climate model and convective parametization. Journal of Climate, 17 (18), 3477-3495.

[\lang_fr]

I am not sure if I believe the “Hurricane results in a Net Gain for the Economy” line of reasoning, since the money spent on fixing hurricane damage, could be spent instead, say, on installing solar panels, if there were no hurricane damage, and installing solar panels would help to mitigate global warming, while fixing what breaks does not mitigate global warming.

200 billion in solar panels, and their installation, would make a big difference, and would create just as many construction jobs and manufacturing jobs, as hurricane damage re-construction. (It’s what economists call the “opportunity cost” which this “net gain for the economy” reasoning misses.)

Re # 298 – I was not questioning the reporting of a theory – you are making the issue complicated – I was saying that measuring the amount of GW or AGW is difficult or almost impossible with instruments — that’s it!

Re # 300 – Again I am not saying that CO2 or other parameters are not changing or we are not measuring them. However, CO2 is small compared with water vapor in the atmosphere, so therefore the total change in greenhouse gases is not as great as the change in CO2. So if CO2 changes 35 percent, the change in greenhouse gas total is less than a percent. Anyway, my point is the same as above – hard to measure the exact amount of influence – good career opportunity!!

RE # 299 – “It indicates a connection, since, over the last few centuries (since people have been inhabiting the coast of Brazil in rather large numbers), no TCs had ever been recorded.

This is likely due to SSTs being sufficiently warm for the formation of these storms when previously, the SSTs inhibited TC/TS/TD formation. This would lead most scientists to conclude that the oceanic warming needed for storm development is likely due to human-induced climate change.”

I have not looked at this area in detail which is why I opened with a question in my response. In other words – Has the SST increasd? When I noted lack of reporting sites, I was quoting from scientific reports. You indicated that people have been living there a long time – but the scientists noted a lack of reports. You have to realize that the records there may not be as good as in North America. To have a report on the coast – the storm has to make landfall. One report noted that there may have been less ship activity therre compared with the north Atlantic so less storms may have been encountered. Even if SST is high enough, you still need the right meteorological conditions to form the storm or hurricane. I believe that there is less cyclone activity in the southern hemisphere than the north.

“Maybe atmospheric temperatures were cooler than normal. However, SSTs were likely not! ”

This report came from scientists who noted the cooler conditions. Have you checked the SST’s? Scientists did indicate that they would have to rely more on satellite photos for observing activity.

Further to Catarina, the following quote is from a UCAR site:

“Already, southern Brazil’s summer had been a strange one. “January and February 2004 were the coldest in 25 years,” notes modeler Pedro Leite da Silva Dias (University of Sao Paolo). Although Catarina was later tagged by some as a possible sign of climate change, the waters over which it formed were actually slightly cooler than average. However, “the air was much colder than normal,” says Dias. This produced the same type of intense upward heat flux that fuels hurricanes, normally seen in warmer waters.”

Other sites indicate that one of the main reasons for a lack of hurricanes there is the wind shear is too great.

You can find studies on this hurricane by searching “Hurricane Catarina”