by Stefan Rahmstorf, Michael Mann, Rasmus Benestad, Gavin Schmidt, and William Connolley

On Monday August 29, Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans, Louisiana and Missisippi, leaving a trail of destruction in her wake. It will be some time until the full toll of this hurricane can be assessed, but the devastating human and environmental impacts are already obvious.

Katrina was the most feared of all meteorological events, a major hurricane making landfall in a highly-populated low-lying region. In the wake of this devastation, many have questioned whether global warming may have contributed to this disaster. Could New Orleans be the first major U.S. city ravaged by human-caused climate change?

[lang_fr]

by Stefan Rahmstorf, Michael Mann, Rasmus Benestad, Gavin Schmidt, and William Connolley (traduit par Claire Rollion Bard)

Le lundi 29 août, l’ouragan Katrina a ravagé la Nouvelle-Orléans, la Louisiane et le Mississipi, laissant une traînée de destruction dans son sillage. Il va se passer du temps avant que le bilan total de cet ouragan soit estimé, mais les impacts environnementaux et humains sont déjà apparents.

Katrina était le plus craint des évènements météorologiques, un ouragan majeur laissant un terrain vide dans une région très peuplée de faible élévation. Dans le sillage de sa dévastation, beaucoup se sont demandés si le réchauffement global pouvait avoir contribué à ce désastre. La Nouvelle-Orléans pourrait-elle être la première ville majeure des Etats-Unis à être ravagée par le changement climatique causé par les humains ?

(suite…)

[\lang_fr]

[lang_es]Traducción disponible aqui (gracias a Mario Cuellar).[/lang_es]

The correct answer–the one we have indeed provided in previous posts (Storms & Global Warming II, Some recent updates and Storms and Climate Change) –is that there is no way to prove that Katrina either was, or was not, affected by global warming. For a single event, regardless of how extreme, such attribution is fundamentally impossible. We only have one Earth, and it will follow only one of an infinite number of possible weather sequences. It is impossible to know whether or not this event would have taken place if we had not increased the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere as much as we have. Weather events will always result from a combination of deterministic factors (including greenhouse gas forcing or slow natural climate cycles) and stochastic factors (pure chance).

Due to this semi-random nature of weather, it is wrong to blame any one event such as Katrina specifically on global warming – and of course it is just as indefensible to blame Katrina on a long-term natural cycle in the climate.

Yet this is not the right way to frame the question. As we have also pointed out in previous posts, we can indeed draw some important conclusions about the links between hurricane activity and global warming in a statistical sense. The situation is analogous to rolling loaded dice: one could, if one was so inclined, construct a set of dice where sixes occur twice as often as normal. But if you were to roll a six using these dice, you could not blame it specifically on the fact that the dice had been loaded. Half of the sixes would have occurred anyway, even with normal dice. Loading the dice simply doubled the odds. In the same manner, while we cannot draw firm conclusions about one single hurricane, we can draw some conclusions about hurricanes more generally. In particular, the available scientific evidence indicates that it is likely that global warming will make – and possibly already is making – those hurricanes that form more destructive than they otherwise would have been.

The key connection is that between sea surface temperatures (we abbreviate this as SST) and the power of hurricanes. Without going into technical details about the dynamics and thermodynamics involved in tropical storms and hurricanes (an excellent discussion of this can be found here), the basic connection between the two is actually fairly simple: warm water, and the instability in the lower atmosphere that is created by it, is the energy source of hurricanes. This is why they only arise in the tropics and during the season when SSTs are highest (June to November in the tropical North Atlantic).

SST is not the only influence on hurricane formation. Strong shear in atmospheric winds (that is, changes in wind strength and direction with height in the atmosphere above the surface), for example, inhibits development of the highly organized structure that is required for a hurricane to form. In the case of Atlantic hurricanes, the El Nino/Southern Oscillation tends to influence the vertical wind shear, and thus, in turn, the number of hurricanes that tend to form in a given year. Many other features of the process of hurricane development and strengthening, however, are closely linked to SST.

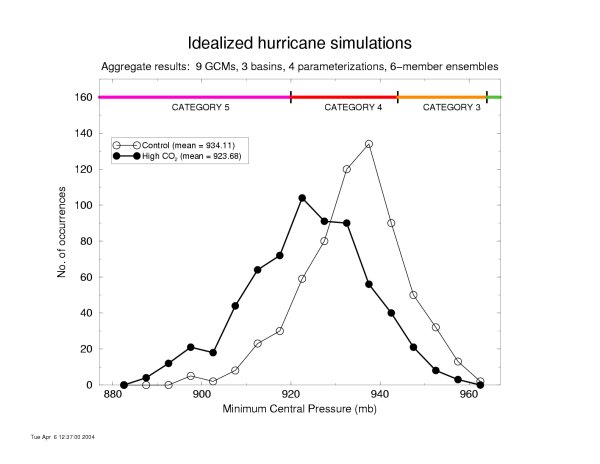

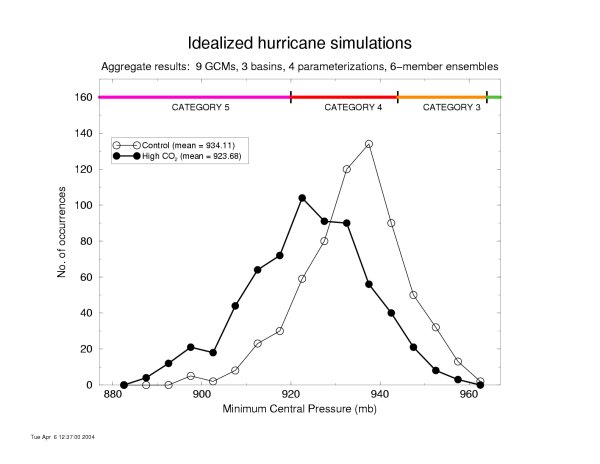

Hurricane forecast models (the same ones that were used to predict Katrina’s path) indicate a tendency for more intense (but not overall more frequent) hurricanes when they are run for climate change scenarios (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Model Simulation of Trend in Hurricanes (from Knutson et al, 2004)

In the particular simulation shown above, the frequency of the strongest (category 5) hurricanes roughly triples in the anthropogenic climate change scenario relative to the control. This suggests that hurricanes may indeed become more destructive (1) as tropical SSTs warm due to anthropogenic impacts.

But what about the past? What do the observations of the last century actually show? Some past studies (e.g. Goldenberg et al, 2001) assert that there is no evidence of any long-term increase in statistical measures of tropical Atlantic hurricane activity, despite the ongoing global warming. These studies, however, have focused on the frequency of all tropical storms and hurricanes (lumping the weak ones in with the strong ones) rather than a measure of changes in the intensity of the storms. As we have discussed elsewhere on this site, statistical measures that focus on trends in the strongest category storms, maximum hurricane winds, and changes in minimum central pressures, suggest a systematic increase in the intensities of those storms that form. This finding is consistent with the model simulations.

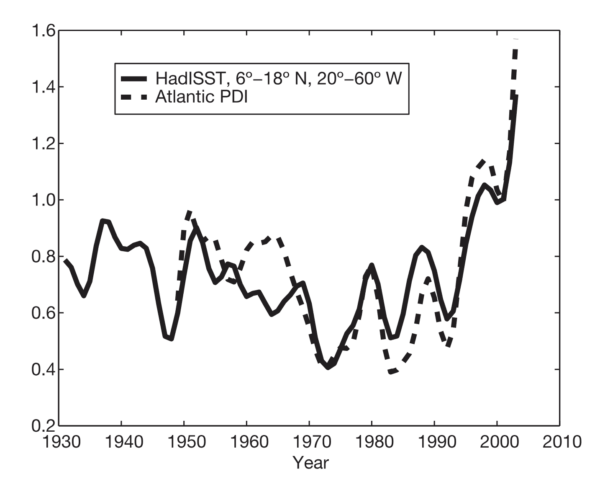

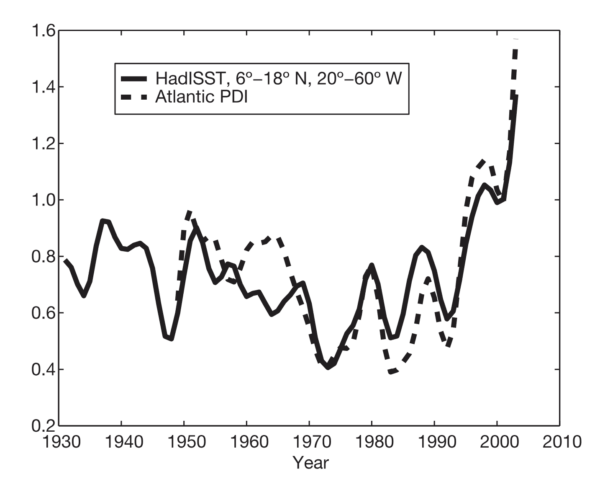

A recent study in Nature by Emanuel (2005) examined, for the first time, a statistical measure of the power dissipation associated with past hurricane activity (i.e., the “Power Dissipation Index” or “PDI”–Fig. 2). Emanuel found a close correlation between increases in this measure of hurricane activity (which is likely a better measure of the destructive potential of the storms than previously used measures) and rising tropical North Atlantic SST, consistent with basic theoretical expectations. As tropical SSTs have increased in past decades, so has the intrinsic destructive potential of hurricanes.

Figure 2. Measure of total power dissipated annually by tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic (the power dissipation index “PDI”) compared to September tropical North Atlantic SST (from Emanuel, 2005)

The key question then becomes this: Why has SST increased in the tropics? Is this increase due to global warming (which is almost certainly in large part due to human impacts on climate)? Or is this increase part of a natural cycle?

It has been asserted (for example, by the NOAA National Hurricane Center) that the recent upturn in hurricane activity is due to a natural cycle, e.g. the so-called Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (“AMO”). The new results by Emanuel (Fig. 2) argue against this hypothesis being the sole explanation: the recent increase in SST (at least for September as shown in the Figure) is well outside the range of any past oscillations. Emanuel therefore concludes in his paper that “the large upswing in the last decade is unprecedented, and probably reflects the effect of global warming.” However, caution is always warranted with very new scientific results until they have been thoroughly discussed by the community and either supported or challenged by further analyses. Previous analysis of the AMO and natural oscillation modes in the Atlantic (Delworth and Mann, 2000; Kerr, 2000) suggest that the amplitude of natural SST variations averaged over the tropics is about 0.1-0.2 ºC, so a swing from the coldest to warmest phase could explain up to ~0.4 ºC warming.

What about the alternative hypothesis: the contribution of anthropogenic greenhouse gases to tropical SST warming? How strong do we expect this to be? One way to estimate this is to use climate models. Driven by anthropogenic forcings, these show a warming of tropical SST in the Atlantic of about 0.2 – 0.5 ºC. Globally, SST has increased by ~0.6 ºC in the past hundred years. This mostly reflects the response to global radiative forcings, which are dominated by anthropogenic forcing over the 20th Century. Regional modes of variability, such as the AMO, largely cancel out and make a very small contribution in the global mean SST changes.

Thus, we can conclude that both a natural cycle (the AMO) and anthropogenic forcing could have made roughly equally large contributions to the warming of the tropical Atlantic over the past decades, with an exact attribution impossible so far. The observed warming is likely the result of a combined effect: data strongly suggest that the AMO has been in a warming phase for the past two or three decades, and we also know that at the same time anthropogenic global warming is ongoing.

Finally, then, we come back to Katrina. This storm was a weak (category 1) hurricane when crossing Florida, and only gained force later over the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico. So the question to ask here is: why is the Gulf of Mexico so hot at present – how much of this could be attributed to global warming, and how much to natural variability? More detailed analysis of the SST changes in the relevant regions, and comparisons with model predictions, will probably shed more light on this question in the future. At present, however, the available scientific evidence suggests that it would be premature to assert that the recent anomalous behavior can be attributed entirely to a natural cycle.

But ultimately the answer to what caused Katrina is of little practical value. Katrina is in the past. Far more important is learning something for the future, as this could help reduce the risk of further tragedies. Better protection against hurricanes will be an obvious discussion point over the coming months, to which as climatologists we are not particularly qualified to contribute. But climate science can help us understand how human actions influence climate. The current evidence strongly suggests that:

(a) hurricanes tend to become more destructive as ocean temperatures rise, and

(b) an unchecked rise in greenhouse gas concentrations will very likely increase ocean temperatures further, ultimately overwhelming any natural oscillations.

Scenarios for future global warming show tropical SST rising by a few degrees, not just tenths of a degree (see e.g. results from the Hadley Centre model and the implications for hurricanes shown in Fig. 1 above). That is the important message from science. What we need to discuss is not what caused Katrina, but the likelyhood that global warming will make hurricanes even worse in future.

_____________________

1. By ‘destructive’ we refer only to the intrinsic ability of the storm to do damage to its environment due to its strength. The potential increases that we discuss apply only to this intrinsic meteorological measure. We are not taking into account the potential for increased destruction (and cost) due to increasing population or human infrastructure.

References:

Delworth, T.L., Mann, M.E., Observed and Simulated Multidecadal Variability in the Northern Hemisphere, Climate Dynamics, 16, 661-676, 2000.

Emanuel, K. (2005), Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years, Nature, online publication; published online 31 July 2005 | doi: 10.1038/nature03906

Goldenberg, S.B., C.W. Landsea, A.M. Mestas-Nuñez, and W.M. Gray. The recent increase in Atlantic hurricane activity. Causes and implications. Science, 293:474-479 (2001).

Kerr, R.A., 2000, A North Atlantic climate pacemaker for the centuries: Science, v. 288, p. 1984-1986.

Knutson, T. K., and R. E. Tuleya, 2004: Impact of CO2-induced warming on simulated hurricane intensity and precipitation: Sensitivity to the choice of climate model and convective parameterization. Journal of Climate, 17(18), 3477-3495.

[lang_fr]

La réponse correcte — celle que nous avons fournie dans les articles précédents (Storms & Global Warming II, Some recent updates and Storms and climate change) — est qu’il n’y a aucune manière de prouver que Katrina était ou n’était pas affectée par le réchauffement global. Pour un seul événement, sans regarder à quel point il est extrême, une telle attribution est fondamentalement impossible. Nous avons seulement une Terre et elle suivra seulement une des infinies possibilités de séquence du temps. Il est impossible de savoir si cet événement aurait eu lieu ou pas si nous n’avions pas eu d’augmentation de la concentration de gaz à effet de serre dans l’atmosphère autant que nous avons. Les évènements du temps résultent toujours d’une combinaison de facteurs déterminants (incluant le forçage des gaz à effet de serre ou les cycles lents naturels du climat) et de facteurs stochastiques (pure chance).

Dû au semi-hasard de la nature du temps, nous avons tort d’imputer un seul événement tel que Katrina au réchauffement global – et, bien sûr, il est juste indéfendable de blâmer Katrina d’un cycle naturel à long terme dans le climat.

Néanmoins, ce n’est pas la bonne manière d’encadrer la question. Comme nous l’avons indiqué dans des articles précédents, nous pouvons en effet dessiner quelques conclusions importantes sur les liens entre l’activité des ouragans et le réchauffement global dans un sens statistique. La situation est analogue à faire rouler un dé pipé : on peut, si on a l’envie, construire un ensemble de dés où les 6 sortent deux fois plus souvent que la normale. Mais si on voulait tirer un six avec ces dés, on ne pourrait pas les blâmer spécifiquement sur le fait que les dés ont été pipés. La moitié des 6 seront tirés de toute façon, même avec un dé normal. Charger les dés a doublé simplement les impairs. De la même manière, bien que nous ne puissions pas tirer des conclusions fermes sur un seul ouragan, on peut tirer certaines conclusions sur des ouragans plus généralement. En particulier, la documentation scientifique à disposition indique qu’il est possible que le réchauffement global fera – et l’a peut-être déjà fait – que ces ouragans ont une forme plus destructive qu’ils auraient eu sinon.

Le lien clé est celui entre les températures des eaux de la mer de surface (abréviation TES – SST en anglais) et la puissance des ouragans. Sans aller trop loin dans les détails techniques sur la dynamique et la thermodynamique impliquées dans les tempêtes tropicales et les ouragans ( une excellent discussion de cela peut être trouvée ici), le lien fondamental entre les deux est assez simple : l’eau chaude, et l’instabilité dans la basse atmosphère que cela crée, est la source d’énergie des ouragans. C’est pourquoi ils surviennent seulement dans les tropiques et durant la saison où les TESs sont les plus élevées (Juin à Novembre dans l’Atlantique Nord tropical).

La TES n’est pas la seule influence sur la formation des ouragans. Un fort cisaillement dans les vents atmosphériques (c’est-à-dire, des changements dans la force du vent et la direction avec la hauteur d’atmosphère au-dessus de la surface), par exemple limite le développement de la structure hautement organisée qui est requise pour la formation d’un ouragan. Dans le cas des ouragans de l’Atlantique, l’ El Niño/Oscillation Australe a tendance à influencer le cisaillement vertical du vent et ainsi, en retour, le nombre d’ouragans qui se forment en une année donnée. Beaucoup d’autres caractéristiques du processus du développement des ouragans et leur force sont, cependant, étroitement liées à la TES.

Les modèles de prévision météorologique des ouragans (les mêmes qui ont été utilisés pour prédire le passage de Katrina) indiquent une tendance pour des ouragans plus intenses (mais, dans l’ensemble, pas plus fréquents) quand ils simulent pour des scénarii de changement climatique (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Simulation d’un modèle de tendance pour les ouragans (d’après Knutson et al., 2004)

Dans la simulation particulière montrée ci-dessus, la fréquence des ouragans les plus forts (catégorie 5) triplent grosso modo dans un scénario de changement anthropique du climat. Cela suggère que les ouragans pourraient, en effet, devenir plus destructifs (1) puisque les TESs tropicales se réchauffent à cause des impacts anthropiques.

Mais qu’en est-il du passé ? Que montrent vraiment les observations du dernier siècle ? Certaines études du passé (par exemple, Goldenberg et al., 2001) soutiennent qu’il n’y a aucune évidence d’une augmentation à long terme dans les mesures statistiques de l’activité des ouragans de l’Atlantique tropical, malgré le réchauffement global en cours. Ces études cependant se sont focalisées sur la fréquence de tous les ouragans et tempêtes tropicaux (réunissant les faibles et les forts) plutôt que de mesurer des changements dans l’intensité des tempêtes. Comme nous l’avons discuté auparavant sur ce site, les mesures statistiques qui se focalisent sur des tendances dans les tempêtes de catégorie la pus forte, le maximum des vents des ouragans, et des changements dans le minimum des pressions centrales, suggèrent une augmentation systématique dans les intensités des tempêtes qui se forment. Cette conclusion est cohérente avec les simulations des modèles.

Une étude récente dans Nature par Emanuel (2005) a examiné, pour la première fois, une mesure statistique de la dissipation de la puissance associée à l’activité des ouragans passés (i.e. “Indice de Dissipation de la Puissance” ou “IDP” — Fig. 2). Emanuel a trouvé une étroite relation entre l’augmentation dans la mesure de l’activité de l’ouragan (qui est susceptible d’être une meilleure mesure du potentiel destructif des tempêtes que les mesures précédemment utilisées) et la hausse de la TES de l’Atlantique Nord tropical, ce qui est cohérent avec les attentes théoriques. Comme les TESs tropicales ont augmenté durant les dernières décennies, alors le potentiel destructif intrinsèque des ouragans l’a fait aussi.

Figure 2. Mesure de la puissance totale dissipée annuellement par les cyclones tropicaux (Indice de Dissipation de Puissance “IDP”) comparée à la TES de Septembre de l’Atlantique Nord tropical (d’après Emanuel, 2005)

La question clé devient alors : pourquoi la TES a t-elle augmenté dans les tropiques ? Est-ce que cette augmentation est due au réchauffement global (qui est presque certainement en grande partie dû à l’impact humain sur le climat) ? Ou est-ce que cette augmentation fait partie d’un cycle naturel ?

Il a été affirmé (par exemple, par le NOAA National Hurricane Center) que la récente reprise dans l’activité des ouragans est due à une cycle naturel, nommé Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (“AMO”). Les nouveaux résultats d’Emanuel (Fig. 2) argumentent contre cette hypothèse comme seule explication : l’augmentation récente de la TES (au moins pour Septembre comme montré dans la figure) est bien en dehors de la gamme des oscillations passées. Emanuel conclut donc dans cet article que “la large hausse dans la dernière décennie est sans précédent, et probablement reflète l’effet du réchauffement global”. Cependant, la prudence est toujours de mise avec des résultats scientifiques très nouveaux jusqu’à ce qu’ils aient été complètement discutés par la communauté et soit supportés, soit affaiblis par des analyses supplémentaires. Des analyses précédentes du AMO et des modes d’oscillations naturelles dans l’Atlantique (Delworth and Mann, 2000 ; Kerr, 2000) suggèrent que l’amplitude des variations naturelles de la SST moyennée sur les tropiques est d’environ 0,1 – 0,2 °C, donc un basculement de la phase la plus froide à la phase la plus chaude peut expliquer jusqu’à 0,4 °C de réchauffement.

Qu’en est-il de l’hypothèse alternative : la contribution des gaz à effet de serre anthropiques au réchauffement de la TES tropicale ? A quelle force s’attend-on ? Une manière d’estimer cela est d’utiliser des modèles climatiques. Diriger par des forçages anthropiques, cela montre un réchauffement de la TES tropicale dans l’Atlantique d’environ 0,2 – 0,5 °C. Globalement, la TES a augmenté d’environ 0,6 °C dans les derniers 100 ans. Cela reflète principalement la réponse à des forçages radiatifs globaux qui sont dominés par le forçage anthropique au cours du XXe siècle. Les modes régionaux de variabilité, comme l’AMO, se neutralisent largement et font une faible contribution dans les changements globaux de TES moyenne.

Ainsi, nous pouvons conclure qu’à la fois un cycle naturel (l’AMO) et le forçage anthropique pourrait avoir fait grosso modo également de larges contributions au réchauffement de l’Atlantique tropical au cours des dernières décennies, avec une attribution exacte impossible jusqu’ici. Le réchauffement observé est probablement le résultat d’un effet combiné : des données suggèrent fortement que l’AMO a été dans une phase de réchauffement pour les deux ou trois dernières décennies, et nous savons aussi qu’au même moment le réchauffement anthropique global est en cours.

Alors, finalement, nous retournons à Katrina. Cette tempête était un faible ouragan (catégorie 1) quand elle a croisé la Floride, et a gagné de la force plus tard au-dessus des eaux chaudes du Golfe du Mexique. La question a posé alors ici est : pourquoi le Golfe du Mexique est si chaud actuellement – combien de cela peut être attribué au réchauffement global et combien à la variabilité naturelle ? Des analyses plus détaillées des changements de la TES dans les régions en question, et des comparaisons avec les prédictions des modèles, apporteront probablement de la lumière sur cette question dans l’avenir. À présent, cependant, la documentation scientifique disponible suggère qu’il serait prématuré d’affirmer que le récent comportement anormal peut être attribué entièrement à un cycle naturel.

Mais, en fin de compte, la réponse à ce qui a causé Katrina est d’une valeur pratique faible. Katrina est dans le passé. Beaucoup plus important est d’apprendre quelque chose pour le futur, puisque cela pourrait nous aider à réduire le risque de tragédies supplémentaires. Une meilleure protection contre les ouragans sera un point de discussion évident dans les mois à venir, auquel, en tant que climatologues, nous ne sommes pas particulièrement qualifiés pour contribuer. Mais la science du climat peut nous aider à comprendre comment les actions humaines influencent le climat. La documentation actuelle suggère fortement que :

(a) les ouragans ont tendance à devenir plus destructifs quand les températures de l’océan augmentent, et

(b) une hausse incontrôlée dans les concentrations des gaz à effet de serre sera fortement susceptible d’augmenter plus les températures de l’océan, surpassant en fin de compte toutes oscillations naturelles.

Les scénarii pour un réchauffement global futur montrent une TES tropicale augmentant de quelques degrés, pas juste des dixièmes de degré (voir par exemple, résultats du modèle du Hadley Centre et les implications montrées pour les ouragans fig. 1). C’est le message important de la science. Ce dont nous avons besoin de discuter n’est pas ce qui a causé Katrina, mais la probabilité qu’un réchauffement climatique fera des ouragans même pires dans le futur.

1. Par “destructif” nous nous référons à la capacité intrinsèque des tempêtes de faire des dommages à l’environnement à cause de sa force. L’augmentation potentielle dont nous discutons s’applique seulement à cette mesure météorologique intrinsèque. Nous ne prenons pas en compte le potentiel pour une destruction accrue (et un coût) due à une population en hausse ou à l’infrastructure humaine.

Références :

Delworth, T.L., Mann, M.E., Observed and Simulated Multidecadal Variability in the Northern Hemisphere, Climate Dynamics, 16, 661-676, 2000.

Emanuel, K. (2005), Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years, Nature, online publication; published online 31 July 2005 | doi: 10.1038/nature03906

Goldenberg, S.B., C.W. Landsea, A.M. Mestas-Nuñez, and W.M. Gray. The recent increase in Atlantic hurricane activity. Causes and implications. Science, 293:474-479 (2001).

Kerr, R.A., 2000, A North Atlantic climate pacemaker for the centuries: Science, v. 288, p. 1984-1986.

Knutson, T.K., and R.E. Tuleya, 2004: Impact of CO2-induced warming on simulated hurricane intensity and precipitation: Sensitivity to the choice of the climate model and convective parametization. Journal of Climate, 17 (18), 3477-3495.

[\lang_fr]

Hi, I’m in a hurry but wanted to ask about societal adaptation (or some such phrase) that in part counters the increasing damage expected from hurricanes, etc. If this adaptation is to be used as an argument to suggest that AGW is not increasing costs in damage or loss of life, then I think there would have to be some accounting of the costs of that adaptation. I’m sorry if I’ve misuderstood, and if I have please correct my misinterpretation. Assuming that some index of damage remains flat, it seems to me that if money was spent on better levees, better pumps, more resistent construction (rather than on something else) in part to ameliorate climatological impacts, if the index ignored those expenditures then that metric is not a good one. In fact, if new technology is brought to bear on the problem because it should provide an improved solution, the cost of the climate change or whatever should in part be measured by the amount that the damage was not reduced as it should have been. This is a poorly-worded way of challenging the idea that we should make comparisons to a fixed baseline. I realise that you’re not comparing to a fixed baseline (because you account for increased population and investment in the affected coastal areas), but Dr. Pielke can you answer regarding whether the costs of adaptation are fully accounted? Thank you.

Re: 151

Steve- Thanks. This is a good question. But the available data actually suggests the opposite effect. Society was arguably less vulnerable in historical times than today. For example, surveys of damage conducted after hurricane Andrew found that homes built more recently experienced more damage. This makes sense if you consider that in the past there was less insurance availability, much less federal disaster assistance, etc. So people had to build in ways that were more resilient. An important “adaptation” to disasters has simply been to become more wealthy as a nation. The federal aid following Katrina could not have occurred in 1900, 1926, 1938 etc. Scholars debate whether programs such as the National Flood Insurance Program have resulted in decreased or increased losses. We have discussed here the challenges of identifying a climate signal in disaster trends, but identification of policy signals is equally as challenging. I think that the balance of evidence suggests that adjustments of past losses are likely underestimates, perhaps significantly so, of what the same storms/events would result in today. But like any other complex issue, more research would be a useful contribution to this relevant, but under-studied area.

Re #144 – now I understand the problem with the PDI! Thanks Roger.

Re 130

Thanks for the explanation of the differences between the effects of CO2 and H2o vapor.

However, with regard to wind I believe the jury is still out. See http://www.ucalgary.ca/~keith/papers/66.Keith.2004.WindAndClimate.e.pdf

for the only study I have been able to find on the possible effects of wind power on climate. There seems to be enough evidence to indicate further study is needed. It appears that there is definitely some effect (and it may even be positive vis a vis greenhouse gases).

I am concerned about politicians jumping on “solutions” for parttially understood problems with consequences that are not known or considered. Most solutions WILL have impacts on the global economy (not talking business, here, but distribution and exchange of goods and services inherent in human societies.) The fact that wind is renewable and “clean” makes it attractive but not necessarily safe. From a systems perspective I would like to see more risk analysis of the climate problems exacerbated by human activity as well as the solutions available.

This thread is an interesting foray into the intersection of science and regulatory policy.

We cannot expect too much from the scientific community in the policy / regulatory arena. Directing research to answer policy questions has some merit but it also has limits. Research should not be overly focused on supporting policy decisions. There is not a straight path to scientific discoveries. Undirected research has value even if it might bring up unforeseen policy implications and might be controversial or distracting.

In regulatory decisions one’s theory, research or publications might not receive the attention the author wants or deserves, but it is naive to think that the most accurate information will always be translated into regulations. Environmental law and regulation making is a very messy process.

Roger some of your comments can be pretty confrontational, but others are more accommodating, its kind of a “good cop – bad cop” thing. More good cop and less bad cop would be better ;)

Re #121 (Bahner on Ausubel, etc.)

Thanks for the links – they make Ausubel’s forecast clearer. His logic is fuzzy though.

Ausubel’s position requires invoking a jump in the decarbonization rate from 0.3%/yr observed in the past (his number) to something well above the growth rate of the economy. If we pretend that the current energy system is all coal, a total shift to gas this century would only get you about 2%/yr decarbonization – still way too slow.

Since he’s not optimistic about renewables and efficiency and places nuclear far out on the horizon (here) sequestration would have to play a big role, and he writes about zero-emission power plants. But why would anyone build a ZEPP (e.g. coal IGCC with sequestration at 45% efficiency and $2000/kW vs. plain IGCC at 55% and $1200/kW) if the price of carbon emissions is 0?

The economy in the past has not been pursuing decarbonization. It’s been pursuing economic gain, and realizing decarbonization as a side-effect. The coal-oil transition was driven by liquid fuel convenience. The oil-gas transition is happening mainly in the power sector due to lower gas cost and high CCT efficiency. But there are reasons to think those trends won’t continue. A large share of future gas may be used for upgrading coal and heavy oil for transport fuel. Coal could easily expand its role in the power sector. Since hydrogen is a carrier, not a source, it doesn’t fundamentally change the outcome, unless its source is carbon free. But again, if you’re making fossil H2, it’s easier to vent CO2 than sequester it.

Finally, even if Ausubel is right and decarbonization magically jumps from 1 to 5%/yr with no policy intervention other than R&D, that might not affect the marginal product of avoided carbon emissions much because the logarithmic concentration-forcing relationship offsets the ~exponential forcing-damage relationship. So, carbon will continue to have a value, and ought to have a price.

RE #147, and the loop-current & gulf stream, have these been (or will these be) impacted by AGW in any way – say, increasing the SST?

Thanks for previous responses (sorry to ask twice): new questions (sorry not sure how to ask it except hitting the one thread that is open). What is a good source to explain the very basics of radiation effects of how greenhouse gases trap heat? For instance, do greenhouse gases vary in their effect based on if sun is shining or not (day versus night, also polar summer, winter). Do they vary in their effect depending on the temperature of the surface? I am an anti-person (i.e. evil) however I think this area is really one where my question is not leading to a gotcha, but just to understanding the unarguable basic physics.

Thanks.

-evil anti-person ;)

[Response: Try here or here or here. The answers to your questions are not much (but it depends) and yes. -gavin]

Gavin I must say, here and here are complete apples and oranges but here (the one in the middle from uchicago) is right on with a caveat). The VUV (<200 nm) absorption due to the O2 Schuman Runge bands essentially wipe out all of the radiation that would be absorbed by methane/CO2 and water vapor as discussed in the here and here. The stratospheric ozone layer takes care of most of the deep UV (<300 nm), so that it has very little flux through the troposphere, and thus very little absorption and thus very little direct effect from sunlight. Thus the comments in here and here are mostly besides the point, because there is no VUV or UV in the regions where greenhouse gases can absorb.

The uchicago here, rightly place the emphasis on absorption and reradiation of IR emission by the greenhouse gases. The caveat is that these molecules can weakly absorb sunlight in the near IR and visible on combination and overtone bands, mostly of water vapor, and on weakly absorbing forbidden transitions such as the Chappius bands of ozone, and for very low concentrations of dimers. See http://www.sron.nl/~ahilleas/wv_retrieval.html (at the bottom) where the lower limit contribution of the visible absorptions of water vapor between 550 and 600 nm are estimated as ~ 0.2 W/m2 (~peak of the solar spectrum) For something a bit more esoteric http://www.templeton.org/wateroflife/doc/pubnew/Vaida.Water_Dimer.pdf

The new paper on TCs and climate change is out

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/309/5742/1807?etoc

I have internet access to it but I don’t have a subscription. Having given it a quick review the conclusions seem similar to Emanuel’ s paper.

Re #160 – The paper seems to cover a 35 year period beginning in the 1970’s. Considering that ocean temperatures have cycles lasting several decades, this study does not give any suprising results. Why not try a 35 year cycle that ends in the 1970’s? Would that show a decline and indicate why there was so much building in hurricane prone areas?

[Response: There is no evidence to support the existence of a multidecadal cycle that influences global mean tropical SSTs. So while one might speculate that some of the changes in tropical Atlantic hurricane statistics could be related to cyclic changes in climate (i.e., the AMO), it is very difficult to argue this for hurricane statistics in other ocean basins, let alone global average hurricane statistics. As discussed in our posting above, Emanuel’s analyses also cast doubt on the proposition that the recent Atlantic basin trends can be dismissed as simply part of multidecadal cycle alone. -mike]

Webster’s study is based on satellite imagery, so only data for the past 35 yrs is available. But all you can ask of a theory is that the available data are consistent with it. So it’s interesting that these data don’t support current theories – the increase in intensity is greater than the theory predicts. So either there’s something else going on or the theory is wrong. “And modeler Thomas Knutson of the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, New Jersey, says, “We would not have expected the signal [of storm intensification] to be detectable at the present time,” based on theory and his modeling of storms under a growing greenhouse. That, he says, prompts the question, “Are these trends real?”“

“Hurricanes Are Getting Stronger, Study Says”:

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2005/09/050916072459.htm

Since the Saffir-Simpson rating system is a wind strength-based scale (unlike the Fujita Scale for tornadoes, which is a damage-based scale), the increase in human inhabitation along the coasts of the Gulf of Mexico and the western Atlantic Ocean does not figure into the number of Category 4s and 5s.

What is startling is that this increase in inhabitation is happening while the danger to coastal residents is rising. It is like people are blissfully ignorant to the consequences of such actions. I guess Hurricane Katrina may (and will hopefully) change this alarming trend.

The level of discussion on this board is terrific, and it is striking how many arguments here can be seen as a world view clash between branches of science, as opposed to disagreements between scientists within a field. The PDI as proxy for “destructiveness” (re #73, etc.) is a perfect example. From a climatologist’s point of view, PDI is about the most objective measure of a storm’s overall strength one could possibly devise, yet the same number lacks any meaning to an economist who’s looking at the financial cost. Many will argue that more powerful storms tend to cause more economic damage, which is intuitively correct, but not really accurate… For if GW is real, the amount of human development on land has a causal connection to the physical power of the hurricane. Looking at Katrina, I would suppose the largest chunk of economic loss is the destruction of homes, yet much of that property value can probably be traced to the US housing boom (see this spooky article) which was in turn fueled primarily by the booming — and polluting — Chinese economy. It is for this kind of interdisciplinary conundrum that all sides must find a common language of values and terms to reach consensus.

Along those lines, I would propose unnecessary loss of human life is the most important measure, yet such a metric does not appear to be posited in the 163+ comments above! That sentiment notwithstanding, I question the implicit assertion in #6 above (re 30,000 deaths in Europe) that rapid climate shifts do not regularly occur without humans involved. My limited understanding is ice cores show rapid changes (ie. several degrees in a few decades) have occured fairly often in the recent geologic past. Objectively, for GW to be really considered a menace, one would want to show it could cause a series of rapid climate shifts which seems doubtful (because if it’s only one shift, then a future cold shift could be avoided for ‘free’).

Re #162 Models, such as GRIB, lack resolution, they can’t interpolate and determine perfect 3D weather between distant fixed points, for instance an inversion between two Upper Air stations, some inversions even 30 miles away. I have measured a warming trend by analysing atmospheric refraction of the sun, at two distinct climatic locations, 2000 miles apart, and found the sun disk getting bigger every year at both locations, sun disks were especially bigger this year. A warmer atmosphere will do that. As shown above, hurricanes get stronger with warmer SST’s, and they merely reflect the state of heat over the region

they pass over. 2005 being very warm year, almost the, or the warmest in Northern Hemisphere met. history, should not be a surprise for those looking back the last 10 years worldwide warmer climate. Whenever the models will get higher resolution, they may calculate or catch up what we are measuring every day, mean time we can clearly see (6 billion of us) that we are responsible for this warming, and that it is likely going faster, in direct proportionality with humanities world wide economic output driven by growth, and sadly of course its by-product, pollution.

“Global warming ‘past the point of no return'”:

http://news.independent.co.uk/world/science_technology/article312997.ece

Hello,

It just came to my attention that a “re-search” of Kerry Emanuel’s intensity index (wind speed cubed) by both Kerry Emanuel and James O’Brien (FSU) reveals no significant linear trends (as argued in Kerry’s Nature paper) if one extends the data set backwards to circa mid-1800’s. Kerry justified his choice of not looking further back than 1935 on increasing uncertainty with respect to inferring wind speeds (if I remember correctly). But they seem to have been able to backtrack in time, and these new results contradict Kerry’s Nature findings. To my knowledge Kerry himself ackowledges these new findings. Another interesting analyses concerning monthly SST anomalies in the tropical Atlantic extracted from reanalysis data from the Hadley Climate Model show a slight negative SST anomaly trend (-0.01 to -0.06 C) (mean average 1950-2004).

I would expect, if these findings are truly legitimate/accurate, that they must eventually be published in the not too distant future.

-inge (meteorologist, Norway)

Re: #167

I just reran the analysis I did in #122 for the full data set. The windspeed corrections are the same as given by Emanuel for other pre-1970 measurements, so one thing that might change the results would be a different windspeed correction for pre-1950 values. If anyone has any insights on how to do a rough correction, please let me know.

I was unable to find any references to this “re-search” on Google news or on the web and Dr. Kerry’s FAQ for the paper on his web site at MIT makes no mention of this. Can you provide any links? Do you know which findings were being contradicted?

Re #162: I get the impression that the research in this field is moving very quickly indeed. This from the interview with Emanuel posted on the AAAS site:

“There is some recent compelling evidence of causality from another source, though. Experiments with climate models at the NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and in Tokyo using the Earth Simulator model have found that with a doubling of CO2, there was an increase in intensity of hurricanes and, simultaneously, an overall decrease in frequency. These results are very much in accord with our findings.”

Re #168: I don’t know much about this, but is there some reason to think Emanuel’s correction isn’t right?

On the other subject, I’m not surprised your search came up empty. There are certain parts of the net where there’s a lot of what some might call “wingnut spam” relating to climate. I’ve seen examples of it similar to that mentioned in #167 that were clearly made up from whole cloth. As I recall, there’s someone (else) in Norway who generates quite a bit of it. Don’t hold your breath waiting for a substantive response, BTW.

As for the claim itself, I think the business about no “linear trend” from 1850 to 1935 is not even wrong. The lack of such a trend would say very little about the 1970-2005 rise unless it showed some kind of long-period oscillation of the sort Gray seems to wish was there, but evidence of such a cycle would be big scientific news indeed (perhaps as big as any implied direct refutation of Emanuel). And yet our new correpondent refers to no such thing. Norway… trolls… hmm.

I suppose a third possibility is that there’s a consistentish trend claimed from 1850 to 1970, followed by that big rise, making for a graph kind of like … Kerry, meet Mike. :)

Re #166,

Presently Barrow Strait has no visible great pack ice , very unusual. It seems that Dr Wadhams may be right, positive forcing may not be well factored in the models and that GW is too conservatively predicted. I think very much in terms of symmetry between distant regions. Lack of Arctic Ocean ice ultimately gave Katrina’s warmer Gulf of Mexico SST’s, worldwide heat has reached a new balance .as it does every day. Simultaneous warming at all distant regions on Earth is clearer then ever, the science is understood, but may be not the rate .

[some inflammatory remarks have been deleted -moderator].

Re #168: Regarding my first post, the source is originally from Dr. James J. O’Brien, Director of the Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies at Florida State University (http://www.coaps.fsu.edu/). I myself received this “tip” from NASA Goddard/Norwegian Space Centre (Dr. Paal Brekke).

Mr. O’Brien’s results are presumably so “fresh” that any “googling” wouldn’t highlight any “hits”. Mr. O’Brien claims he’s discussed his results with Mr. Emanuel. He also claims his results show that the recent surge in intensity is well within observed natural variability if one extends the data set backwards to 1850, as opposed to a cuttoff in 1935.

Note that I also wrote in my original post that if these results are truly genuine, then I would expect them to appear in the peer reviewed litterature sooner than later. If not, well then it certainly won’t warrent any further attention until someone does publish contrary results.

I would suspect that working with such a short data set (1935-2005) is a challenge with respect to “proving” the existence of statistically significant trends beyond observed natural variability..?

But from purely physical reasoning, I myself also find it hard not to expect that a warmer climate should raise the theoretical limit of maximum hurricane intensity if all environmental factors (sst, upwelling, shear, lifetime, etc.) coincide in time and space to produce optimal conditions for development and maintenance (which Kerry Emanuel has argued in previous research).

Re #168 again: Possibly you were referring to tbe discussion on Emanuel’s FAQ page that subsequent to submission of his paper he talked to Chris Landsea about this wind speed issue, made an adjustment and re-did his calculations. Apparently this did not shift any conclusions, though. Maybe you should just email him and ask for the information you want.

Re #171: Your first post (#167) said new work “by both Kerry Emanuel and James O’Brien (FSU) reveals no significant linear trends (as argued in Kerry’s Nature paper) if one extends the data set backwards to circa mid-1800’s. (…) But they seem to have been able to backtrack in time, and these new results contradict Kerry’s Nature findings. To my knowledge Kerry himself ackowledges these new findings.” This was an amazing and provocative claim for which no sources were listed.

Your second post (#171) says instead: “Mr. O’Brien claims he’s discussed his results with Mr. Emanuel. He also claims his results show that the recent surge in intensity is well within observed natural variability if one extends the data set backwards to 1850, as opposed to a cuttoff in 1935.” This is way, way different. It no longer claims collaboration between O’Brien and Emanuel or agreement by Emanuel with any such new results.

The fact that O’Brien has this point of view is not news. He is, after all, rather active in sceptic circles; see, e.g., http://www.techcentralstation.com/images/obrientranscript.htm . Interestingly, this related Washington Post story from just a couple of days ago quotes O’Brien but makes no reference to this supposed new research: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/09/15/AR2005091502234.html . There is no reference to any such recent revelation on O’Brien’s own site: http://www.coaps.fsu.edu . Emanuel’s site and other MIT sites (e.g. http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2005/hurricane-quotes.html, which includes a link to a radio statment from last Monday) also have nothing on it. None of these sources would involve any search lag. All that I can find from O’Brien on the web are repeated claims that a linkage of the historic hurricane record going back to 1850 shows a recurring cycle, and that this explains everything. Emanuel, Webster and his co-authors, their peer reviewers, Nature and the AAAS (publishers of Science) were all aware of this view held by O’Brien and Bill Gray (among others, although Chris Landsea seems to have gotten a little quieter post-Webster), yet the results of neither paper were affected. I look forward to seeing a peer-reviewed paper demonstrating that all of this work is in error.

The Dr. Brekke you quote is apparently a sceptic of the discredited (my opinion) solar school (see e.g. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_depth/sci_tech/2000/climate_change/1026375.stm and http://zeus.nascom.nasa.gov/~pbrekke/articles/halifax_brekke.pdf ), although perhaps his views have changed since my web search found nothing on this more recent than 2002.

So, at this point there doesn’t appear to be a lot of content here. I apologize for perhaps over-reacting, but it seems fairly clear that you posted a sceptic-generated rumor and clothed it as fact. Please be more careful. (And BTW I take my own advice; it took me over two hours to review all of the material I cited above.)

Hmmm.. In the Jim O’ Brien interview is the link cited in # 173

http://www.techcentralstation.com/images/obrientranscript.htm .

He states:

“But what’s amazing is if you actually looked at the trends in the Atlantic Ocean – the region where hurricanes form from five north to 20 north – from Africa over to the United States, it’s actually cooling down. So, I mean yes, there are hotspots in the globe which are warming up, but not in the Atlantic hurricane formation region. So, their theory doesn’t really hold water.”

But when I look at the single figure in Kevin Trenberth’s recent Science paper (“Uncertainty in Hurricanes and Global Warming”, vol 308, 1753-54) the mean SSTA averaged over the tropical Atlantic (“10 N to 20 N excluding the Caribbean west of 80 W”) sure doesn’t indicate recent cooling. Seems unlikely that the slight difference in O’ Brien’s (5 N to 20 N) vs. Trenberth’s ( 10 N to 20 N) averaging region could account for this. Gee whiz, I’m confused…

[Response: The difference is the time period involved. O’Brien is using data from 1950 to 2003 over which time the mean over the area has barely warmed (and some parts have indeed cooled). However, over the last 30 years there has been significant warming, and over the longer term (say 1900) there has been warming as well. The upshot is that there is cyclic activity in the Atlantic basin, but not over the whole of the tropics – and this is what is significant about the Webster et al results. – gavin]

[Response: O’Brien seems to have relied purely on the linear trends over the period, which is not well suited to the task if the upturn, as Emanuel notes, is only in the most recent decade. Perhaps more of an issue, O’Brien placed as much emphasis on winter trends as summer or fall trends. One can rightfully question whether cooling trends in winter are relevant to this debate. Emanuel focused only on the part of the year (early Fall) corresponding to peak formation of Hurricanes, which would appear more appropriate. -mike]

The Independent newspaper article linked in Comment 166 misrepresents the views of the US National Ice and Snow Data Centre (NISDC). The article imples that ‘the scientists’ believe all Arctic ice melt is caused by man-made global warming. What the NISDC actually says is”

“Fossil fuel consumption and the resulting increase in global temperatures could explain sea ice decline, but the actual cause might be more complicated. The Arctic Oscillation (AO) is a seesaw pattern of alternating atmospheric pressure at polar and mid-latitudes. The positive phase produces a strong polar vortex, with the mid-latitude jet stream shifted northward. The negative phase produces the opposite conditions. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the AO flipped between positive and negative phases, but it entered a strong positive pattern between 1989 and 1995. This flushed older, thicker ice out of the Arctic, leaving the region with younger, thinner ice that was more prone to summer melting. So sea ice decline may result from natural variability in the AO. Growing evidence suggests, however, that greenhouse warming favors the AO’s positive mode, meaning recent sea ice decline results from a combination of natural variability and global warming.” (http://nsidc.org/sotc/sea_ice.html)

Thus, the scientists believe man-made global warming is a component, not necessarily the most important, and not a proven one. An analogy is in those who seem to claim that the destruction of New Orleans was ’caused’ by global warming, even if you accept that it was a significant component of the hurricane’s severity. Such over-claiming and over dramatisation of the impacts of global warming does not represent the scientific consensus (eg. as represented by IPCC), and devalues the quality of the scientific debate.

“Nothing unusual-ists” always fail to look at the whole planet, always selecting a region in favour of their premise, and then they pounce on that single area forcing the view that the rest of our planet is likewise the same, they should be regarded as climate isolationists, basically thinking that one region has absolutely nothing to do with others. Of course, everything is linked, and there is no way to consider even ponder an active Hurricane season when the Northern Hemisphere climate is cooler.

Do you believe that proper levee and protection policies against a hurricane of Katrina’s strength was/is even possible? And if it was possible to protect against Katrina’s severity, to what extent would it have made a difference?

[Response: Unfortunately this is way outside of our competence -gavin]

RE #175,

What happened in the Arctic, was a slow, very slow and gradual decrease in cooling, caused by progressively longer warmer seasons, with a feedback loop of warm air reducing albedo, with reduced albedo increasing warm air. Arctic daily sun positions now is the same as the end of March, yet today’s (Resolute) temperature -2 C does not compare with end of March -35 C, albedo plays a role in this especially with all that missing ice and clouds. Familiar Arctic climate cycles are by no means comparable to what we are experiencing here now, with much more warmer weather encroaching almost unabated since 1998. So the referred to Arctic Oscillation has no semblance to anything in human memory here. It is plainly getting warmer in an unprecedented way. With this Polar region warmer, so is your region where-ever it is down South. This is where the debate is, a failure to link one region’s climate with another ultimately leads to a poor understanding of climate anywhere. All these oscillations, ENSO, AO and AMO’s are influenced way beyond their recognized borders. Not recognizing so yields nothing useful.

There’s an excellent column by James Risbey, Karl Braganza, and Thomas Homer-Dixon in today’s (Sept 19) Globe & Mail from here in Canada.

The article is available online only to those with subscriptions, but some university libraries may have access to this newspaper.

I’d highly recommend the article.

Re#177, as a civil engineer who often deals with drainage issues and storm events and who has “always known” something like this was going to happen to New Orleans, I would say “theoretically yes, but realistically, probably no” to question #1.

From what I understand, the levees were designed to withstand a Cat 3 without breaching. However, they were supposed to over-top under the storm surge in a stronger storm, and the most common explanations I have seen given for the levee breaches is that the over-topping wore down the surface soil and foundation on the inner face (the side which faces New Orleans), which led to the structural failures. So even a Cat 3 hurricane may have created the same failure results (I think there has been levee over-topping in New Orleans from lesser hurricanes which hit farther away, so I’m not sure how well it could really handle a Cat 3 or lesser storm with Katrina’s path in the first place).

Some people are under the impression the levee system in New Orleans was constructed and is improved on time-to-time, like a typical building. This is far from the case. The levee system is a hodge-podge of construction that settles faster than the rest of New Orleans and constantly needs to be built-up and re-inforced. In a lot of ways, the levee system is no “better” than it was 30-40 yrs ago. Construction methods may be better these days, but the regular levee work is/was basically a maintenance effort and not much of an improvement effort. I believe I heard on one of the post-Katrina stories on the History Channel that parts of the levee have settled as much as 4 feet in a year. The discussion on that show of the future of New Orleans included: (1) a huge series of sea walls similar to what the Netherlands has; (2) restoration of the wetlands outside of New Orleans; (3) levees within the levee system so that if one levee fails, only part of the city is flooded; (4) taller levees; and (5) return of some of the city back to its original swamp state.

With #1-4 in place, the flooding effects of Katrina would likely have been diminished significantly. However, only items #2-4 had really been seriously considered prior to Katrina, and they were part of a plan of construction through 2050 – far too late to do anything. #5 will be VERY unlikely because of politics, but it seems to be a frequent suggestion of many engineers (including myself). #3 will also be politically difficult, but I think it could happen. #1 will be an immense engineering and construction undertaking that could take decades – arguably among the biggest ever in the US.

So even if the US and New Orleans got serious about these items 20-30 yrs ago, it’s uncertain exactly how much would actually have been in place for Katrina.

Al Gore weighs in on the climate change-Katrina link:

http://news.ft.com/cms/s/7c972c82-27b2-11da-ac98-00000e2511c8.html

Re #179: On growing greenhouse petunias in Nunavut? :) Seriously, when posting something like this please paste in the first paragraph or two and a link (not a copyright problem, BTW), or at least some kind of summary, and maybe something about the authors if you think they’re especially worth listening to; otherwise, I think it’s pretty certain that nobody’s going to follow up, however useful the article may be.

Re #180: I wonder if #2 (wetlands restoration) will really be possible of the Mississippi is left in its present unnatural course. Also, my understanding is that it was not the levees themselves that failed, but rather flood walls (essentially large reinforced concrete fences set in the middle of levees). They were supposedly designed to withstand foundation overtopping, but whether it was that or direct failure may never be known since the evidence largely washed away.

RE #175, and AGW being only one small component (if at all) of vanishing arctic ice and hurricanes. Did you ever hear about the straw that broke the camel’s back?

While scientists in a detached fashion equally investigate all components, it’s mainly those small human-caused components that I’m concerned with. Afterall, there’s not much I can do about purely natural processes. Not much I can do by myself either regarding GHGs, even though we’ve lowered ours 75%+ from our 1990 (when we started) emissions. But I’m doing what I can, even if insignificant in the larger scheme of things. I’m hoping beyond hope that by removing one tiny straw I might be able to save at least a baby camel’s back, or ease its pain.

RE #166 (arctic melting) & hurricanes, I have no idea on the science, but if the arctic ice melts a lot more, would the Northern Pacific ocean warm more (say, during the summer, when they have midnight sun), and could this lead to hurricanes or typhoons possibly hitting LA or San Francisco?

I read somewhere that even if hurricanes intensify with AGW, they will be pretty much in the same tropical/subtropical areas as today. But I wonder…

Re: #171

I hope that my post was not the cause of the “inflammatory remarks”. I was posting late on a Friday afternoon and I apologise if my phrasing was off.

[the inflammatory remarks were related to another post, not yours. -moderator].

Re: #172

Thanks. I did note several corrections listed there, although I have not had time to adjust my model yet. Hopefully some time in the next few days, especially if I can get Landsea’s coefficient.

My question was more whether the poster in #167 had the pre-1950 corrections that must have been used. As it now appears that there is no there there, the question is probably irrelevant now.

Re the loop current (147, 156), with the reminder that I’m not a climatologist, just an avid reader — this

http://ctr.stanford.edu/ResBriefs03/dedietrich.pdf

Center for Turbulence Research

2003

Nonlinear Gulf Stream Interaction with the western boundary current: observations and a numerical simulation

Fascinating description; color maps; far more that possible to quote about what the “loop current” is and where Atlantic temperature variations are moving around.

And note their Section 4 — contemplating what happens if deep warm water currents change in a way that changes the current temperature in areas where methane hydrates are in equilibrium, suggesting the possibility of a rapid large scale release of methane gas.

Quietly nightmarish, to this reader. I don’t know of other discussion in the literature looking specifically at changes in warm currents in relation to known methane hydrate deposits. But this paper has plenty of footnotes to pursue the thought.

Here’s the link to the G&M article from #179:

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/Page/document/v4/sub/MarketingPage?user_URL=http://www.theglobeandmail.com%2Fservlet%2Fstory%2FRTGAM.20050919.wxcoclimate19%2FBNStory%2FspecialComment%2F&ord=68582812&brand=theglobeandmail&redirect_reason=2&denial_reasons=none&force_login=false

Katrina has generated a lot of discussion. However the greatest death toll was from a typhoon that hit Bangladesh in November, 1970 killing 200,000 to 500,000 people.

Re: #188,

That may be true. However, infrastructure in Bangladesh is terrible, while in the developed world, it tends to be fairly solid. Also, the population density of Bangladesh is very high, while less so in the developed world, so a greater number of people were in grave danger of dying or being left homeless (at the very least).

Post #188 does not effectively rebut the premise that climate change is happening and that events such as Katrina (and its significant intensity) are at least a partial result of climate change. A couple of years before Hurricane Andrew struck Florida and the Gulf Coast in 1992, a typhoon struck Bangladesh resulting in the death of approximately 140,000 people. (I think this Bangladesh storm struck in 1989.)

The fact that two very intense tropical cyclones occurred so soon after each other may mean that more frequent TCs will occur and to a higher intensity as a result of climate change, which may result in even more devastating effects. As a previous (and very recent) study has found, Category 4 and 5 storms may be on the rise, and climate change could very likely be the reason for this increase.

Re#182: For all intents and purposes, the wall is part of the levee system. The reason for failure is probably pure conjecture at this point. There are other possible natural explanations for the failure, such as creating a slurry and pushing-out earth below the wall and weakening the support that way, construction flaws in the walls, design flaws, material flaws, debris strikes that damaged the wall, etc. There have been other explanations ranging from loose barges striking the levee to the intentional use of explosives.

As far as wetlands go, there has been talk of re-routing the path ships take south of New Orleans, constructing silt diversion channels, augmentation by dumping sand from other locations, etc.

Re evacuations – When Typhoon Talim hit China on September 1, 2005, they were able to evacuate about a half million people, with only a hundred or so dying.

In reply to Steven Berg (189): the observation of two strong storms occuring 3 yrs apart on different continents does not on its own make any case that climate change is a contributary factor to either frequency or intensity when compared to conclusions of the IPCC TAR (published several yearas after these events and therefore very unlikely to have missed them) – stating:

“There is no compelling evidence to indicate that the characteristics of tropical and extratropical storms have changed… Owing to incomplete data and limited and conflicting analyses, it is uncertain as to whether there have been any long-term and large-scale increases in the intensity and frequency of extra-tropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere. Regional increases have been identified in the North Pacific, parts of North America, and Europe over the past several decades. In the Southern Hemisphere, fewer analyses have been completed, but they suggest a decrease in extra-tropical cyclone activity since the 1970s.”

The paper at the start of this discussion is of clear scientific value, representing a progression of work since the TAR, but it appears naive to suggest that every extreme whether event is significantly influcenced by climate change.

To draw in a legal distinction again, the discussion appears to be between guilty and innocent, while the evidence points to not proven. Given this what is a policy maker to do? I submit that nothing is a very bad choice given the likely outcomes even if there is no casual link. However, I would go much farther than what Roger Pielke advocates because the possibility of a casual relationship between storm frequency and anthropic climate change has not been falsified, and the possibility of stronger tropical cyclones appears to have increasing evidence in its favor. Given the catastrophic consequences of even one Cat 5 storm making landfall in a populated area, strong actions beyond those necessary if there were no possible relationship are called for.

Re 193 – We will never be able to stop a hurricane or earthquake, no matter what its strength is. The most significant things we can do is be prepared personally and with respect to government agencies. That means supplies, funds, communication, tents, transportation to be available with less than 24 hours notice. On a longer time period, we must also be prepared for droughts, wet spells, cold and warm spells.

http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=Tech_Central_Station

RE #193 my legal understanding (as a layperson) would be that we cannot make a criminal case re the link between CC & hurricane intensity of a specific hurricane, which requires “beyond a resonable doubt” (sort of like a scientific standard of p<.05), but there could be a civil case, which requires a "preponderance of evidence." When I did jury duty the judge instructed it meant "more likely than not" or above 50%. It seems we may be at or above that level of certainty on this. Then re a "precautionary approach," which might be above 20% or even 10% certainty (depending on the severity of the possible harm), we've got all the proof we need.

192,

I think naive would be to postulate that Arctic Air can’t influence the Gulf of Mexico climate. Perhaps those crop destructive extremely cold Arctic airmass blasts destroying oranges in Florida come from the State of Minnessota?

The reverse influence is true as well. In the Arctic we benifit from warm air advection every day of the year. There is a continuous exchange of heat going back and forth from North to South, South to North. A heat balance is achieved continuously everywhere else on Earth as well. The case for climate change is made when the average temperature of the world increases or decreases. Recent world wide records indicate a steady increase, pretty much found in all regions, which portends something good for Hurricanes, beasts born from heat. Looking back with hurricane statistics will not be comparable to present day history, since we are breaking new temperature increase records almost every year, unfamiliar climates are breaking loose. For those seeking certainty, we know a few of them: The only thing certain is hurricanes weaken or die over land and or colder water. With equal certainty, a warmer planet will lead to hurricanes/typhoons range widening with some having greater intensity, this in itself gives cause to ponder, should we do something to reduce the number of coming storms? Or just compile statistics?

By the way, 1997 proved to be a very interesting year, with a very large and cold Arctic Vortex in the spring (coldest in memory……… care for an Arctic Oscillation anyone?) , there were very few Hurricanes for the entire same year: 5.

I have a few questions on your article. Please don’t read between the lines, I’m not laying a trap and have no other motive than learning.

One, you base much of this discussion on data from past storms, for instance comparing PDI over the last few decades, etc. It seems to me that we can now measure a storm more accurately and continuously than, say, 1900. The Galveston Hurricane of 1900 is measured as a Cat 4, at landfall. Is there any way to account for its strength before landfall, say if it fell from a Cat 5 to 4 just before landfall? Or, more broadly, when does information become as sophisticated as it is today?

Second, does the PDI measure a storm at landfall, at its peak, or using some average? What I’m getting at, I’m sure you’ve figured out, is whether the PDI’s trend could have anything to do with how accurately we measure storms now, as opposed to in previous periods? Are models used, or direct measurements? At what period does the PDI determination on actual data become perfectly consistent with modern measurements? Again, I’m not laying a poorly disguised trap, I’m trying to learn.

Third, you describe the AMO as a decades based cycle. What about a centuries-long cycle? I’ve studied history, and I’ve seen that the world undergoes centuries-long warming and cooling cycles which affect argriculture, settlement patterns, glaciers, even wars and the fates of empires. Do hurricane researchers have any models, or direct methods, to measure how active a season may have been in, oh, say 1705, based on possible long duration climactic trends?

I’m interested in how a long duration model of hurricane activity could show increases and decreases in hurricane strength, frequency and size, which could give a more clear image of how much GW is calling the shots, so to speak. I’m also curious about evidence, and how accurate hurricane measurements are now compare to 1950, or 1920, etc.: it’s the history student in me.

Hi Joe,

I’m not an expert on these matters, but here would be my answers to your questions:

1) “Or, more broadly, when does information become as sophisticated as it is today?”

We’ve only had satellite data since the late 1960s-early 1970s. Before that, back to approximately the end of WWII, the U.S. had airplanes doing measurements for North Atlantic hurricanes.

I found this website that talks about measurements at sea that extend back to 1851 for the North Atlantic hurricane basin:

http://www.theroyalgazette.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20050909/MIDOCEAN/109090137

But I don’t understand how *sea-based* measurements could exist back to 1851, because I can’t believe anyone could or would sail a ship into the eye of a hurricane, to measure the point of lowest pressure:

http://ww2010.atmos.uiuc.edu/(Gh)/wwhlpr/hurricane_preswind.rxml?hret=/indexlist.rxml

2) “Second, does the PDI measure a storm at landfall, at its peak, or using some average?”

Stefan Rahmstorf explains the PDI as, “Concerning the power dissipation index: this is the wind speed cubed, integrated over the surface area covered by the hurricane and over time.”

So it’s the wind speed *cubed*, integrated over the surface area covered by the hurricane (i.e., for a given wind speed, a larger surface area produces a larger PDI), integrated over the life of the storm. So it’s not just at landfall, and it’s not a peak. It covers the entire lifetime of the storm, over the entire area covered by the storm.

3) “What I’m getting at, I’m sure you’ve figured out, is whether the PDI’s trend could have anything to do with how accurately we measure storms now, as opposed to in previous periods?”

Well, the PDI trend shown in Figure 2 only goes back to 1945…the start of the airplane-monitoring period. So the trend in PDIs only includes two “periods” (monitoring by planes, and monitoring by satellites). Further, there was no real “jump” up or down in PDI in the period of the early 1970s when satellites started to be used. So I don’t think the trend in PDI is significantly affected by planes-vs-satellites as PDI measurement methods.

Hi, I was wondering if based on the global warming situation and the way that the hurricanes have gotten worse and more frequent over the last 30 years, is it realistic to expect a possible category 6 or 7 in the near future? And what would that mean for the US. Could we ever be ready for such a storm of that magnitude? Thankyou