2020 has been an unusual and challenging year in many ways. One was the record-breaking number of named tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic (and the Carribean Sea). There has been 30 named North Atlantic tropical cyclones in 2020, beating the previous record of 28 from 2005 by two.

A natural question then is whether we can expect this high number in the future or if the number of tropical storms will continue to increase. A high number of such events is equivalent to a high frequency of tropical cyclones.

But we should expect fewer tropical cyclones generally in a warmer world according to the IPCC “SREX” report from 2012, and those that form may become even more powerful than the ones that we have observed to date:

There is generally low confidence in projections of changes in extreme winds because of the relatively few studies of projected extreme winds, and shortcomings in the simulation of these events. An exception is mean tropical cyclone maximum wind speed, which is likely to increase, although increases may not occur in all ocean basins. It is likely that the global frequency of tropical cyclones will either decrease or remain essentially unchanged…

So how does this conclusion relate to the number of tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic with a new record this season? One reason to look in more detail at the North Atlantic is because its observational record is believed to be more complete and more reliable than for other regions around the world.

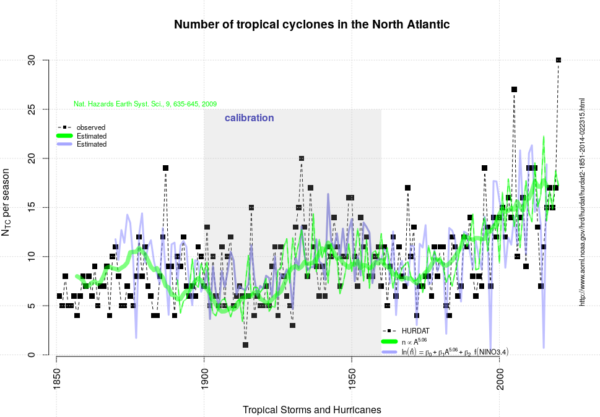

The observational record may also suggest that the number of tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic has increased slowly over the 50 years in addition to year-to-year fluctuations around this trend (black symbols in Fig 1).

We know that the number of cyclones is sensitive to the time of the year (hence, hurricane seasons), phenomena such as El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO), and geography (the ocean basin shape and the latitude). We also know that the sea surface needs to be warmer than 26.5°C for them to form.

The role of sea surface temperature is indeed an important factor, and from physical reasoning, one would think that the number of tropical cyclones depends on the area of warm sea surface (sea surface temperature exceeding 26.5°C).

One explanation for why the area is a key factor may be that the probability of finding favourable conditions with right ‘seed’ for organised convection (e.g. easterly waves) and no wind shear increases when there is a greater region with sufficient sea surface temperatures.

The area of warm sea surface is mentioned in the IPCC SREX that dismisses the expectation that an increase in the area extent of the region of 26°C sea surface temperature should lead to increases in tropical cyclone frequency. Specifically it says that there is

a growing body of evidence that the minimum SST [sea surface temperature] threshold for tropical cyclogenesis increases at about the same rate as the SST increase due solely to greenhouse gas forcing.

On the other hand, there has also been some indication that the number of tropical cyclones does seem to be proportional to the area to the power of 5: (Benestad, 2008). When this relationship is extended to recent years, as shown with the green and blue curves in Fig 1, we see an increase that this crude estimate more or less follows the observed number of evens.

Global warming implies a greater area with sea surface exceeding the threshold of 26.5°C for tropical cyclone genesis. Also, the nonlinear dependency to implies few events and little trend as long as

is below a critical size. The combination of a nonlinear relationship and a critical threshold area could explain why it is difficult to detect a trend in the historical data.

There is some good news in that is limited by the geometry of the ocean basin. Nevertheless, a potential nonlinear connection between the number of tropical cyclones and

is a concern. If this cannot be falsified, then the tropical cyclones represent a more potent danger than anticipated by the IPCC SREX conclusions. So let’s hope that somebody is able to show that the analysis presented in (Benestad, 2008) is wrong.

Fig 1. Observed (black symbols) and estimated (green and blue curves) number of named tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic and the Caribbean Sea after (Benestad, 2008). Source: “demo(tropicalcyclones)”.

References

- R.E. Benestad, "On tropical cyclone frequency and the warm pool area", Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, vol. 9, pp. 635-645, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/nhess-9-635-2009

“The observational record may also suggest that the number of tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic has increased slowly over the 50 years…”

I’m surprised you didn’t mention one contribution to this could be improvements in observational methods over that period. I’m almost certain we are seeing more very short lived weak storms and subtropical storms that would have been missed back then, and hurricanes that would have been previously classed as tropical storms (there was at least one hurricane in the last 10 years that looked like a sloppy mess on satellite).

https://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/historical-atlantic-hurricane-and-tropical-storm-records/

Shear Frustration,

I keep reposting this comment/question from Andrew Sipocz (#13 UV) in the hope that someone familiar with the topic will answer it for him… not an area I’ve paid attention to:

“What’s going on here? Check out the negative trend line of vertical wind shear for the Main Development Region of Atlantic tropical cyclones on page 30 by Dr. Klotzbach.

https://tropical.colostate.edu/Forecast/2020-11.pdf

What we’ve heard in the past is that with AGW, climate models show increasing wind shear and thus fewer tropical cyclones in the future, though stronger ones (due to increased ocean temperature). This seems to show that AGW may bring both more (lower wind shear) and stronger tropical cyclones to the Atlantic. This seems to be the case with more, and more rapidly intensifying storms since 2005.”

Anyone?

If the stratosphere is also cooling, wouldn’t that increase the pressure differential that drives cyclones, and reduce the necessary sea-surface temperatures for them to form?

Or is that not enough of a change to be significant?

Glad to see this discussion. Particularly interesting is the point about increases warm-sea area, even if it remains a bit inconclusive at this point.

I’d be interested, too, about the potential effects of an *extended* hurricane season. All this piece says about that is the very embryonic comment that “We know that the number of cyclones is sensitive to the time of the year (hence, hurricane seasons).” So, if ‘off-season’ months warm, what happens?

One metric would be hurricane frequency during ‘edge months’ such as December. Is there enough data to draw a conclusion, or at least give an indication?

If TS Wilfred had occurred in 1860, would it have been named?

Adam Lea @1 – I am sure that some short-lived tropical storms were missed early in the satellite days, say 1970s and 80s. However, the north Atlantic shipping routes are fairly well used, and I would be very surprised if enough was missed to account for more than a small fraction of the over 50% increase since then. What I find more surprising is that there isn’t much overall trend in the 100 years preceding 1970, although it was clearly to the advantage of ships to stay well away from a tropical storm if they could.

Keith Woollard @4,

I don’t think naming is of itself relevant to the count of storms. There was, after all, an un-named sub-tropical storm included in the then-record-breaking 28 storms of the 2005 season, between TS Stan and TS Tammy.

The large number of US storms was predicted, but underestimated.

Something to do with La Nina (sorry for fuzzy term, but my brain is fuzzy). But an extraordinary year and in many ways counterintuitive for a La Nina year as well.

For anyone interesting in looking up tropical storm data, Wikipedia does a remarkable job, in general and in specific. For example:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_United_States_hurricanes

Other of W’s sites also have excellent maps. For example, see “season summary” here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_Atlantic_hurricane_season

Can anyone provide a quick explanation for why they say the “minimum SST threshold for tropical cyclogenesis increases at about the same rate as the SST increase”? Is there a physical reason given or just statistics?

#4 as I understand it storms were normally only named in those days if they caused major damage or inconvenience and then often by the saints name of the day or the name of an island or landmass hit by it.

3: “So, if ‘off-season’ months warm, what happens?”

I’m not a tropical cyclone expert, although it is an area of my work. If wamring sea surface temperatures are having an effect on Atlantic tropical cyclone genesis, I would expect this to happen more at the beginning of the season than at the end. In June and July, the atmospheric conditions (e.g wind shear) are conducive in localised regions for tropical cyclones to form, but the sea surface temperature in the main development region is insufficient, so they typically form in the Caribbean/Gulf in earfly season. At the end of the season, the sea surface temperature is still conducive but the wind shear increases over the Atlantic and Caribbean, and the relative humidity decreases, so tropical cyclone genesis ceases in the main development region, then later the Caribbean, sometimes storms for in the sub-tropics late season e.g. 2005.

One thing I am curious about is whether climate change might be having an effect on tropical cyclone genesis in the sub-tropical Atlantic. There seem to have been several years recently where activity in the sub-tropics has been high, even when main development region activity has not been notable. 2018 is a good example, lots of activity north of 25N, anything tracking across the MDR sheared apart or choked with dry air.

Is there any good reason to think that warmed oceans equals longer storm season and stronger storms? It seems like that would simply follow, but I don’t study storms much, so maybe I have missed something.

Mike

S Molnar@9 Yes, there is a physical reason to suspect that “minimum SST threshold for tropical cyclogenesis increases at about the same rate as the SST increase.” A tropical cyclone is a self-sustaining organized system of tropical convection (i.e. thunderstorms). In order to achieve this, the thunderstorms that develop must be consistently strong enough to reach to the tropopause or higher – which requires that the warm moist air from near the sea surface must have enough potential instability to keep rising to the tropopause when lifted. However, the height of the tropical tropopause is established by other thunderstorms. So, warming oceans drive up the general height of the tropopause through repeated formation of towering thunderstorms, even if these aren’t organized into a tropical cyclone. Thus, a general warming of the tropical oceans ought to create an overall environment requiring taller thunderstorms in order to initiate tropical cyclogenesis. This means that warmer background tropical SSTs tend to require higher local SSTs in order to “compete” and create a self-sustaining tropical cyclone.

correction at 12: Is there any good reason to NOT think… should be obvious, but want to be clear

14: One reason would be if models predicted that mean atmospheric conditions in a warming climate became more hostile for tropical cyclones. It doesn’t matter how warm the sea surface temperature is if the atmosphere is bone dry and full of subsidence with 60 kts of vertical wind shear, you are not getting any tropical cyclone development.

It might be that atmospheric conditions do become less conducive, which seems to be consistent with the prediction that number of storms remains constant or decreases slightly, and intensity of the strongest storms increases. If the atmosphere does become less conducive for tropical cyclones on average, there will still be periods when the atmospheric conditions are optimal, and if a disturbance is available to take advantage, that disturbance has a greater potential to develop into a very intense hurricane. Hence you may not get more storms forming in the future, but any storm that does form has a higher potential intensity due to a warmer sea surface temperature.

@5 (plus a couple of others)…

Your question is freshman science. It’s like suggesting to a pro qb he should look downfield before passing.

When examining any historical record for scientifically worthwhile purposes, Job #1 in any analysis data is to ask precisely the question you asked and make sure to erect a criterion or set of measurable criteria for inclusion/exclusion on a single set of terms. Historical naming conventions aren’t the important factor. Wind speed, cyclone size, rainfall amounts, central pressures.

It’s why some alcohol thermometer on the side of some hut in some random Australian outback settlement (reported by DS in another thread as such a disproof) really doesn’t “disprove” global warming. It proves an individual total scientific incompetence from the lowest levels on up. Most science-bound students still in high school wouldn’t make this error. But our resident deniers can.

Sorry MAR@7, I was just using the same nomenclature as the post. Read the second sentence.

If a hurricane in 1860 was only recorded due to re-analysis of one ship’s log, do you really think the difference in numbers is due to anything other than observational improvements? Particularly as Rasmus is keen to say

“One reason to look in more detail at the North Atlantic is because its observational record is believed to be more complete and more reliable than for other regions around the world.”

So the observational record is clearly imperfect, but he doesn’t ever suggest that that is why the increase has happened?????

Using the same argument you could equally well ask why almost all the Atlantic storms in the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries are near the US coast, whereas nowadays they are spread right across the Atlantic. Perhaps someone should tie this easterly migration to CO2 increases?

This post is a new low for RC

…. and it’s curious that the start of the rise in hurricane frequency corresponds exactly to when they set up the NHRP and started flying plans to look for them!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Hurricane_Research_Project

KW 17: So the observational record is clearly imperfect, but he doesn’t ever suggest that that is why the increase has happened?????

BPL: Uncertainty is not your friend. It could work against you as well as for you.

19: “Uncertainty is not your friend. It could work against you as well as for you.”

True in the general case, irrelevant to this specific case under discussion. There are solid reasons why tropical storm, hurricane and intense hurricane numbers are very likely to have been undercounted in the past, relating to changes/improvements in observing practices. Therefore the low bias in past records has to be addressed before any conclusions sbout trends over decades to over a century are drawn. That is why there has been a reanalysis project underway going through each historical decade to improve the hurricane records. Keith makes a sound argument, just because it doesn’t fit the tendency of trying to attribute something to climate change doesn’t make him, or anyone else, a denier. If you don’t agree with his argument, put a solid counterargument down as to why you think changes in observational practices are not likely to have a significant effect on past records and therefore historical trends in Atlantic tropical cyclones.

John Pollack #13,

Any chance you can relate this to wind shear?

See page 30:

https://tropical.colostate.edu/Forecast/2020-11.pdf

#20, adam–

Right. But if you go back to the specifics of Keith’s argument and then compare them to the specifics of this post, you find a bit of a discrepancy.

The post:

Keith:

So, noting that the National Hurricane Research Project dates from 1955, which was 65 years ago, one sees immediately that Keith is making critiques based on data already excluded from the part of “the observational record” described as significant in the post. Some would call that “Straw Man argumentation.”

(One also sees that he’s wrong to connect the rise in hurricane frequency “exactly” to the NHRP, as there were about 15 years worth of decline following its establishment, but that’s a bit secondary.)

As jgn said in #16, it’s important to “ask [research questions] precisely.”

Adam Lea: put a solid counterargument down as to why you think changes in observational practices are not likely to have a significant effect on past records and therefore historical trends in Atlantic tropical cyclones.

AB: Yes, but not so stark and you place the burden on the wrong party. The question at hand is whether changes in observational practices are the dominant (as opposed to merely significant) factor in the historical trend in Atlantic tropical cyclones. A secondary, hopefully stupid question, is whether scientists have attempted to factor in observational changes into their analysis.

This looks like yet another denier pointing out the glaringly obvious, along with the implied insult that scientists as a group are so clueless that they’ve all surely missed such a DUH! thing for decades on end. THAT amazing story about how clueless all those eggheads really are is the extraordinary claim that requires extraordinary evidence.

@20 ” put a solid counterargument down as to why you think changes in observational practices are not likely to have a significant effect on past records and therefore historical trends in Atlantic tropical cyclones.”

Nope. This was done a decade ago by the cited author, Benestad.

In historical statistical work with time series, you ALWAYS have biases and changes over time to deal with. The 2008 report underlying this post does in fact do so using a number of methods–primary among them is using equivalent records in other areas at the same historical times.

What YOU need to do FIRST is show how the Benestad’s strategies misaligned the changing technologies and methodologies (biases) over time. What exactly did Benestad get wrong? Be specific.

Also, READ the Benestad paper, which you most surely have not given your comments. It doesn’t matter if you don’t have access to a research library, the journal is open source though their site is a bit clumsy for those not familiar with academic journals. The article is also quickly and very easily googled on researchgate using scholar.google.com. Read it carefully before commenting further on methodology. You just look silly otherwise.

All this is Historical Time Series 101 which I infer you have never taken given your statement. It is an extremely challenging area needing huge amounts of careful validating, equating, debiasing, and contextualizing each individual observation first before any statistical test is done at all. This is kinda like all the original Mann work getting the right wood samples to analyse first and then aligning everything appropriately BEFORE actual statistical testing–which they did …all denier propaganda aside).

18 I am curious about this business of flying “plans”?

AL 20: Keith makes a sound argument, just because it doesn’t fit the tendency of trying to attribute something to climate change doesn’t make him, or anyone else, a denier.

BPL: If you don’t think Keith is a denier, you obviously haven’t been here very long.

You guys are so obsessed trying to prove anything any “denier” says is wrong you are willing to throw logic out the window.

Let me expand on my very first comment…..

If TS Wilfred had occurred in 1860, would it have been noted?

If TS Wilfred had occurred in 1910, would it have been noted?

If TS Wilfred had occurred in 1940, would it have been noted?

If TS Wilfred had occurred in 1955, would it have been noted?

If TS Wilfred had occurred in 1970, would it have been noted?

If TS Wilfred had occurred in 1980, would it have been noted?

If TS Wilfred had occurred in 1990, would it have been noted?

If TS Wilfred had occurred in 2000, would it have been noted?

Clearly as we progress through time, the odds of being recorded increase. Slowly at first as the only real change is volume of shipping traffic, and then there was local radar, air traffic, NHPR flights, powerful weather radars, balloons and buoys, satellites, significant increase in air and sea travel (not necessarily in that exact order).

Benestad 2008 provided most of the displayed graph, but the

“The observational record may also suggest that the number of tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic has increased slowly over… 50 years…”

has nothing to do with the referenced paper, nor it’s conclusions. Benestad 2008 seeks to correlate the short term variation of temperature with TC count. As such slow variation in observational quality is irrelevant.

He says clearly in the paper …

“The ability to detect TCs in the open Atlantic has increased

substantially over time as aircraft reconnaisance and (in the

1970s) satellite monitoring have become available. These

improvements in detection tools may have led to enhanced

probability of detection of weak and remote TCs over time,

although estimated maximum potential intensities of tropical

cyclones appear to show some agreement with the observations

(Henderson-Sellers et al., 1998).”

Whether the change in observational accuracy is merely “significant” rather than “dominant”, it is “glaringly obvious” and needed to be said as this long term trend is the thrust of the post

Zebra #21 Thanks for linking the discussion of the 2020 Atlantic tropical cyclone season.

Regarding a possible relationship between rising subtropical SSTs and decreasing zonal wind shear, I’m out of my area of expertise. There are some real experts who understand the issues far better than I do.

With that caveat, I feel fairly safe making a few general comments. The graph you mentioned on p.30 certainly indicates a substantial decline in zonal winds in the subtropical Atlantic basin during the peak Aug.-Oct. hurricane season in the last 40 years. It also matches the observed rise in tropical cyclone numbers during those years, and is a contributing factor. What is unclear to me is whether this trend should be attributed more to background AGW, manifested in rising SSTs, or more to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. We’re certainly in a warm/active phase of the AMO, but the authors also note that the AMO is “likely related to fluctuations in the strength of the oceanic thermohaline circulation.” There’s plenty of expert discussion of those fluctuations elsewhere on this board.

Another issue outside my expertise is the decline in subtropical zonal shear in the Atlantic basin, as opposed to planetary scale. My understanding of current modeling is that it indicates a slow long-term increase in overall shear, which ought to slow or cancel the rising potential tropical cyclone numbers due to rising SSTs from AGW. This certainly contradicts what has been happening in the Atlantic basin since 1979, so we need to be alert to a possible discrepancy between climate model behavior and reality – and a need to get a better handle on these MDOs so that we can separate the effects of AGW from medium term cycles. Or, perhaps the Atlantic basin will exhibit a different behavior from the much larger Pacific basin.

Again, I welcome expert commentary here. I have not closely followed current research in this area.

KW, #27–

Really? Then I suppose the graph from the “referenced paper” showing precisely that there has been a slow increase over 50 years ought to count as independent evidence for that proposition.

KW suggests by implication that there could have been an increase in detection probability not only from 1860-present, but also from 1970-present, but does not present any evidence that that has been the case. And in fact, that suggestion actually flies in the face of his previous (incorrect) claim that the advent of NHRP flights accounts for all the putative observational bias (#18):

Apparently he has now discovered that there could also be contributions from “local radar, air traffic.. powerful weather radars, balloons and buoys, satellites, significant increase in air and sea travel…”

But I note that the satellite era began in the 70s, and that there were powerful weather radars, lots of transoceanic air traffic, and of course those NHRP flights, considerably before that. To which I’d add that numerical modeling weather analysis began during the 60s and 70s too, and quite early on began to display the ability to infer storm systems that escaped direct detection. (For instance, the excellent book “A Vast Machine” cites an instance that occurred in the Sahara–IIRC!–when communications failures delayed weather reports until after the dissipation of a cyclonic system. But the system was nevertheless modeled more or less correctly, as was confirmed when the delayed observations were eventually reported.) This capability surely gave added effectiveness to NHRP and similar efforts by directing attention to areas requiring it.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Numerical_weather_prediction#History

Personally I doubt there’s much change in the effective probability of TS detection during that 1970-present span–and while that certainly qualifies as an argument from incredulity, I think my incredulity is at least as valid as KW’s.

24: “This was done a decade ago by the cited author, Benestad.”

Thank you. I’ll have a read of that paper, assuming it is the one referenced here, which somehow I missed.

23: “This looks like yet another denier pointing out the glaringly obvious, along with the implied insult that scientists as a group are so clueless that they’ve all surely missed such a DUH! thing for decades on end.”

What it sounds like to you and what it is in reality aren’t the same thing. I’ve never made or implied such a statement, so that is a straw man, don’t try and put words in my mouth. I have suggested that data inhomogenities could be a contribution, I have not claimed it is the dominant factor or that it explains all the trend, or that scientists are clueless. Several scientists who work in the field of tropical cyclones have pointed out that changes in observational practices can result in artificial trends in tropical cyclone statistics, hence why I queried why it wasn’t mentioned in the above article. Now someone has pointed out a paper that addresses this I can hopefully improve my understanding.

It is an unfortunate and incidious characteristic of one or two on this blog to be very quick to throw out the DENIER accusation at anyone who questions anything relating to climate change attribution or similar. If I question something, it is because there is a gap in my understanding or it contradicts my understanding, so my aim is to bridge the gap, not to engage in a pointless and tiresome exercise in trying to deny potential consequences of climate change, so I object to being slapped with that label.

KMK@29 – like talking to a brick wall.

“Really? Then I suppose the graph from the “referenced paper” showing precisely that there has been a slow increase over 50 years ought to count as independent evidence for that proposition.”

– no, and that is my point. The increase in observation is not evidence of increased activity.

And you emphasise all in my comment and the word wasn’t even there????

Quote me next time, don’t change the meaning of what I said

John Pollack #28,

John, I can’t take credit for spotting the data that contradicts the well-known projection of increasing wind shear. See my #2 above. (But I have been persistent in trying to get someone to answer Andrew’s question, without much success.)

Anyway, you seem as close to an expert in this area as there is for RC regulars.

When I saw your description of increasing height for the tropopause, I thought there might be a connection, whether physical or due to distortion of the measurements.

KW, #31–

Sigh. That “brick wall” you perceive, Keith, isn’t me; it’s logic. I’ll walk through it again–er, make that “I’ll trace its outlines for you again”–and in more depth this time.

Starting with the less important, you complained that I “changed the meaning” of #18 and I was adjured to “quote.” Actually, I did–and almost the entirety of the comment, at that. Go back and have a look.

The crucial bit reads like this:

(My emphasis.)

There are two senses which might apply here: it could “correspond” in time and/or in magnitude. As I noted, though, it doesn’t correspond very exactly in time–there’s a 15-year ‘lag’ before the rise kicks in. So it would seem to be magnitude, which would make “exactly” equivalent to the ‘plan flights’ accounting more or less completely for that rise. If you meant something else, I’m sure we’re all ears. But to me, “exactly” and accounting for “all” of the rise are reasonable equivalents.

But more importantly, you are claiming that the observed rise in North Atlantic TC storm frequency “is not evidence of increased activity,” to use your exact words. This is frankly ludicrous. Of course it is evidence for exactly that! If we ‘see’ something, it’s clearly evidence that it *may* be there.

Now, you can claim that it is not *conclusive* evidence–and you are correct, as far as that goes, because the issue then becomes “How strong is that evidence?” You are apparently claiming that the observed rise is accounted for by:

Let’s systematize that:

Remote sensing: “Satellites”

Radar: 1) “local radar”; 2) “powerful weather radars”

Purposeful reconnaissance: “NHPR flights”

Static reconnaissance: “Balloons and buoys”

Observations from conveyances: 1) “air traffic”; 2) “significant increase in air and sea travel”

Now, while it is absurd to claim that the number of North Atlantic hurricanes observed has “nothing to do with the referenced paper” [i.e., Benestad (2008)]–since if the number of hurricanes is biased, then the correlation with the area of the “warm pool” will also be affected–it is true that Benestad (2008) did not itself investigate numbers of TCs. Rather, it obtained the North Atlantic data from HURDAT. HURDAT has quite the history, which one can look up easily, but a seminal paper is Jarvinen (1983), which can be found here:

https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/7069/noaa_7069_DS1.pdf

So let’s apply Jarvinen’s Figure 1, “Technical advances in systems for observing tropical cyclones, 1871 through 1980,” to the list above.

Remote sensing: Sun-synchronous, 1960; Geo-statonary, 1967; GS infrared, 1973.

Radar: Coastal radar network, 1955.

Purposeful reconnaissance: Organized reconnaissance, 1948.

Static reconnaissance: Radiosonde network, 1937; Ocean data buoys, 1972.

Observations from conveyances: Ship logs, 1871; Marine wireless telegraphy, 1905; Aircraft satellite data link, 1978.

Note that of these 10 categories of observations, only one is newer than 1973. Crucially, there seems to be a consensus that the single most powerful tool is satellite sensing, which is why it’s common among TC researchers to speak of “pre-satellite” and “post-satellite” periods.

An example of this usage is found in Chang & Guo (2007)–entitled Is the number of North Atlantic tropical cyclones significantly underestimated prior to the availability of satellite observations?–which compared TC detections via ship to total detections during recent times to examine the potential for TC undercount during historical times, and hence bias in the trends:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2007GL030169

In a sense, this paper is not strictly relevant to topic at hand, since we’re concerned with trends from 1970, and the satellite era already begins in 1960. But it’s valuable to move from a qualitative assessment, which is what we have so far, to a quantitative one, which Chang & Guo provide for earlier decades, thus also providing a limit for the possible effects during the satellite era.

Quoting from their results:

So, if prior to 1965, only 1.2 open-ocean TCs were likely to be missed per decade* on average, there’s clearly very little room for improvement *during* the satellite era. (And I think there’s also a reasonable presumption that the improvement would more closely resemble a step change rather than a “slow increase,” since it doesn’t take a lot of satellites to achieve pretty complete coverage for crude detection purposes.)

I think your claim that there may have been a significant bias due to observational change post 1970 is pretty well refuted by the above considerations.

And–refuting also your accusation about motivated reasoning–I don’t care because ‘I want to prove a denier wrong.’ After all, the consensus seems at present to be that AGW will worsen storms, but *not* increase their frequency, so North Atlantic cyclone frequency (and thus our present debate) isn’t really relevant to climate change denialism (or “alarmism”, if you prefer). I care because I think it’s important to get an accurate picture of what research says, or doesn’t say.

*(The wording in the Results quoted is a bit ambiguous, but comparing Tables 2 & 4 clarifies that the frequency is given per decade, not per year.)

jgnfld(24): “ This looks like yet another denier pointing out the glaringly obvious, along with the implied insult that scientists as a group are so clueless that they’ve all surely missed such a DUH! thing for decades on end.”

Adam Lea (30): “What it sounds like to you and what it is in reality aren’t the same thing.”

It was a figure of speech – so don’t make too much hay out of it – it means in effect: “based on your arguments, the most likely explanation for them is …”. And _this_ you can’t just wave off with your paternalistic line, but have to falsify it by providing a BETTER explanation for your posts.

Adam Lea (30): “ I’ve never made or implied such a statement”

Since nobody said that you “ made ” such a statement – there is not point to break down the door that nobody closed.

As for “ never implied“: if a layman not knowing the literature could point to a problem that scientists working in the field for decades in his opinion didn’t account for – WHAT ELSE did you IMPLY?

Adam Lea (30): It is an unfortunate and incidious characteristic of one or two on this blog to be very quick to throw out the DENIER accusation at anyone who questions anything relating to climate change attribution or similar.

The layman not knowing the literature implying that scientists are either morons or cheats because they missed what the layman figured out by himself – is the MO of practically all internet deniers.

So, if you walk like a duck and quack like a duck – don’t be surprised if jgnfld who in his life probably saw 100s? 1000s? ducks, says that you “ look like another duck“. By their quack you shall know them ? ;-)

So if we suddenly could detect all storms from some year XXXX (your choice KMK) then you are suggest the observational record should have a step at that point and anything non-step-like must be due to actual changes rather than observational changes. Look back at the last real paragraph of my #17.

I suggested that there is an observable easterly shift in TC locations. Now I would be hugely surprised if that was real and (IMHO) is an observational artifact. Using your logic, if we plotted the average longitude against time then there should be a flat line, step down at XXXX and then flat line. Using my logic, I would expect a flat line until XXXX, followed by a gradual slope. Have a look and you try and decide.

https://photos.app.goo.gl/gbj2w2wNpSTZe2Y87

Or better still, do it yourself – don’t trust what someone else tells you even if (especially if) they claim to be an expert. The data comes from here:-

https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/

It is the first download of the “Best Track Data (HURDAT2)” section

Here is the script I used to average, but assuming you are younger than me, you could probably do it in R rather than unix that dinosaurs like me use.

awk -F “,” ‘BEGIN {oldyear=1851} {

if ( NF >=5 ) {

if ( substr($1,1,4) == oldyear ) {

counter+=1

summ_lat+=substr($5,1,5)

summ_long+=substr($6,1,6)

}

else {

print oldyear,summ_lat/counter,summ_long/counter

counter=1

summ_lat=substr($5,1,5)

summ_long=substr($6,1,6)

oldyear=substr($1,1,4)

}

}

}’ $1

It’s 10 minutes work