The “end of the world” or “good for you” are the two least likely among the spectrum of potential outcomes.

Stephen Schneider

Scientists have been looking at best, middling and worst case scenarios for anthropogenic climate change for decades. For instance, Stephen Schneider himself took a turn back in 2009. And others have postulated both far more rosy and far more catastrophic possibilities as well (with somewhat variable evidentiary bases).

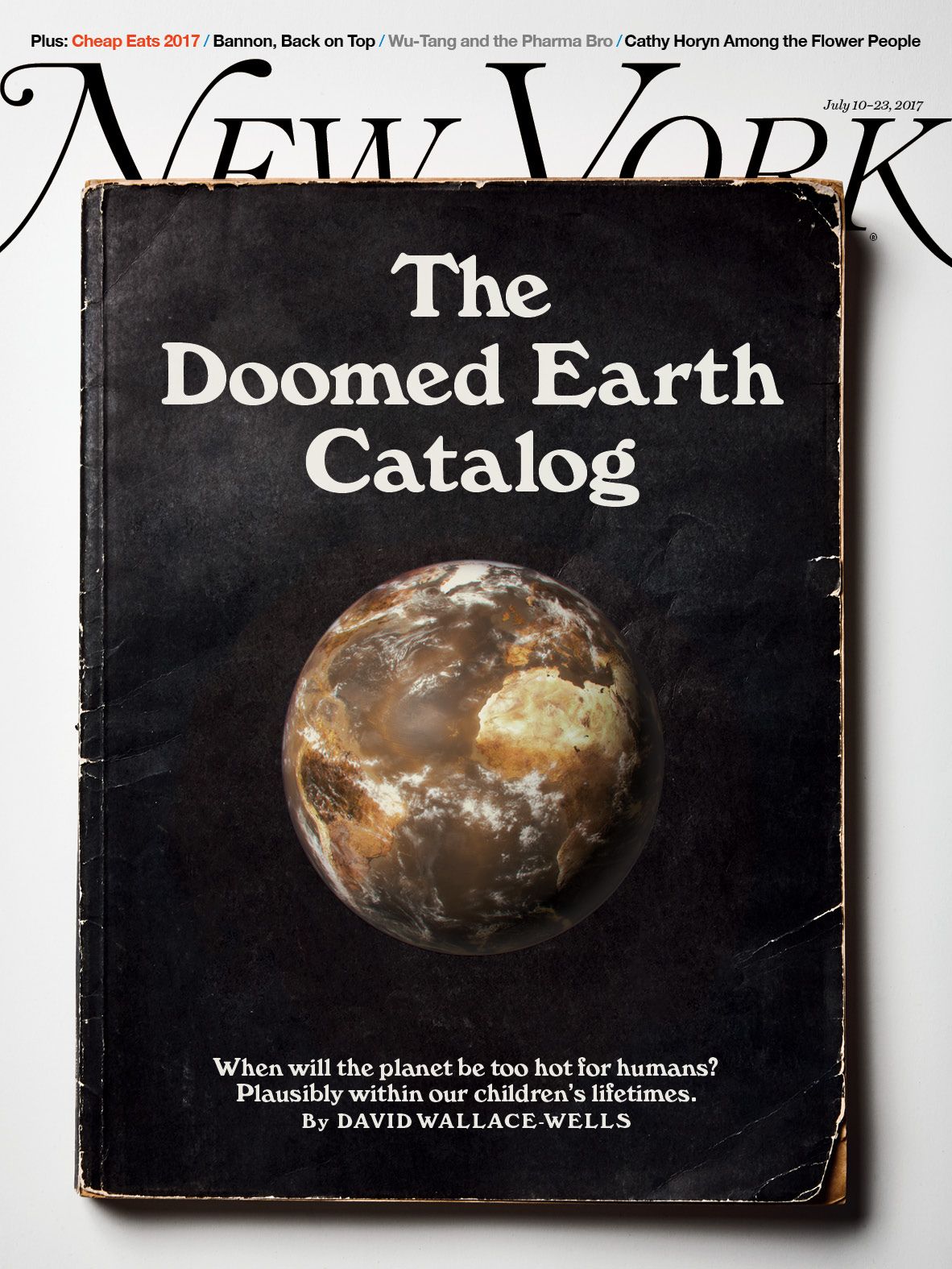

This question came up last year in the wake of a high profile piece “The Uninhabitable Earth” by David Wallace-Wells in New York magazine. That article was widely read, and heavily discussed on social media – notably by David Roberts, Mike Mann and others, was the subjected to a Climate Feedback audit, a Salon Facebook live show with Kate Marvel and the author, and a Kavli conversation at NYU with Mike Mann this week as well. A book length version is imminent.

In a similar vein, Eric Holthaus wrote “Ice Apocalypse” about worst-case scenarios of Antarctic ice sheet change and the implications for sea level rise. Again, this received a lot of attention and some serious responses (notably one from Tamsin Edwards).

It came up again in discussions about the 4th National Assessment Report which (unsurprisingly) used both high and low end scenarios to bracket plausible trajectories for future climate.

However, I’m not specifically interested in discussing these articles or reports (many others have done so already), but rather why it always so difficult and controversial to write about the worst cases.

There are basically three (somewhat overlapping) reasons:

- The credibility problem: What are the plausible worst cases? And how can one tell?

- The reticence problem: Are scientists self-censoring to avoid talking about extremely unpleasant outcomes?

- The consequentialist problem: Do scientists avoid talking about the most alarming cases to motivate engagement?

These factors all intersect in much of the commentary related to this topic (and in many of the articles linked above), but it’s useful perhaps to tackle them independently.

1. Credibility

It should go without saying that imagination untethered from reality is not a good basis for discussing the future outside of science fiction novels. However, since the worst cases have not yet occurred, some amount of extrapolation, and yes, imagination, is needed to explore what “black swans” or “unknown unknowns” might lurk in our future. But it’s also the case that extrapolations from incorrect or inconsistent premises are less than useful. Unfortunately, this is often hard for even specialists to navigate, let alone journalists.

To be clear, “unknown unknowns” are real. A classic example in environmental science is the Antarctic polar ozone hole which was not predicted ahead of time (see my previous post on that history) and occurred as a result of chemistry that was theoretically known about but not considered salient and thus not implemented in predictions.

Possible candidates for “surprises in the greenhouse”, are shifts in ecosystem functioning because of the climate sensitivity of an under-appreciated key species (think pine bark beetles and the like), under-appreciated sensitivities in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, or the North Atlantic overturning, and/or carbon feedbacks in the Arctic. Perhaps more important are the potential societal feedbacks to climate events – involving system collapses, refugee crises, health service outages etc. Strictly speaking these are “known unknowns” – we know that we don’t know enough about them. Some truly “unknown unknowns” may emerge as we get closer to Pliocene conditions of course…

But some things can be examined and ruled out. Imminent massive methane releases that are large enough to seriously affect global climate are not going to happen (there isn’t that much methane around, the Arctic was warmer than present both in the early Holocene and last interglacial and nothing similar has occurred). Neither will a massive oxygen depletion event in the ocean release clouds of hydrogen sulfide poisoning all life on land. Insta-freeze conditions driven by a collapse in the North Atlantic circulation (cf. “The Day After Tomorrow”) can be equally easily discounted.

Importantly, not every possibility that ever gets into a peer reviewed paper is equally plausible. Assessments do lag the literature by a few years, but generally (but not always) give much more robust summaries.

2. Reticence

The notion that scientists are so conservative that they hesitate to discuss dire outcomes that their science supports is quite prevalent in many treatments of worst case scenarios. It’s a useful idea, since it allows people to discount any scientists that gainsay a particularly exciting doomsday mechanism (see point #1), but is it actually true?

There have been two papers that really tried to make this point, one by Hansen (2007) (discussing the ‘scientific reticence’ among ice sheet modelers to admit to the possibility of rapid dynamic ice loss), and more recently Brysse et al (2013) who suggest that scientists might be ‘erring on the side of least drama’ (ESLD). Ironically, both papers couch their suggestions in the familiar caveats that they are nominally complaining about.

I am however unconvinced by this thesis. The examples put forward (including ice sheet responses and sea level rise, and a failed 1992 prediction of Arctic ozone depletion, etc) demonstrate biases towards quantitative over qualitative reasoning, and serve as a lesson in better caveating contingent predictions, but as evidence for ESLD they are weak tea.

There are plenty of scientists happy to make dramatic predictions (with varying levels of competence). Wadhams and Mislowski made dramatic predictions of imminent Arctic sea ice loss in the 2010s (based on nothing more than exponential extrapolation of a curve) with much misplaced confidence. Their critics (including me) were not ESLD when they pointed out the lack of physical basis in their claims. Similarly, claims by Keenlyside et al in 2008 of imminent global cooling were dramatic, but again, not strongly based in reality. But these critiques were not made out of a fear of more drama. Indeed, we also made dramatic predictions about Arctic ozone loss in 2005 (but that was skillful).

The recent interest in ice shelf calving as a mechanism of rapid ice loss (see Tamsin’s blog) was marked by a dramatic claim based on quantitative modelling, later tempered by better statistical analysis (not by a desire to minimise drama).

Thus while this notion is quite resistant to being debunked (because of course the reticent scientists aren’t going to admit this!), I’m not convinced that there is any such pattern behind the (undoubted) missteps that have occurred in writing the IPCC reports and the like.

3. Consequentialism

The last point is similar in appearance to the previous, but has a very different basis. Recent social science research (for instance, as discussed by Mann and Hasool (also here)) suggests that fear-based messaging is not effective at building engagement for solving (or mitigating) long-term ‘chronic’ problems (indeed, it’s not clear that panic and/or fear are the best motivators for any constructive solutions to problems). Thus an argument has been made that, yes, scientists are downplaying worst case scenarios, but not because they have a personal or professional aversion to drama (point #2), but because they want to motivate the general public to become engaged in climate change solutions and they feel that this is only possible if there is hope of not only averting catastrophe but also of building a better world.

Curiously, on this reading, the scientists could find themselves in a reverse double ethical bind – constrained to minimize the consequences of climate change in order to build support for the kind of actions that could avert them.

However, for this to be a real motivation, many things need to be true. It would have to widely accepted that downplaying seriously bad expected consequences would indeed be a greater motivation to action, despite the risk of losses of credibility should the ruse be rumbled. It would also need the communicators who are expressing hope (and/or courage) in the face of alarming findings to be cynically promoting feelings that they do not share. And of course, it would have to be the case that actually telling the truth would be demotivating. The evidence for any of this seems slim.

Summary

To get to the worst cases, two things have to happen – we have to be incredibly stupid and incredibly unlucky. Dismissing plausible worst case scenarios adds to the likelihood of both. Conversely, dwelling on impossible catastrophes is a massive drain of mental energy and focus. But the fundamental question raised by the three points above is who should be listened to and trusted on these questions?

It seems clear to me that attempts to game the communication/action nexus either through deliberate scientific reticence or consequentialism are mostly pointless because none of us know with any certainty what the consequences of our science communication efforts will be. Does the shift in the Overton window from high profile boldness end up being more effective than technical focus on ‘achievable’ incremental progress or does the backlash shut down possibilities? Examples can be found for both cases. Do the millions of extra eyes that see a dramatic climate change story compensate for technical errors or idiosyncratic framings? Can we get dramatic and widely read stories that don’t have either? These are genuinely difficult questions whose solutions lie far outside the expertise of any individual climate scientist or communicator.

My own view is that scientists generally try to do the right thing, sharing the truth as best they see it, and so, in the main are neither overly reticent nor are they playing a consequentialist game. But it is also clear that with a wickedly complex issue like climate it is easy to go beyond what you know personally to be true and stray into areas where you are less sure-footed. However, if people stick only to their narrow specialties, we are going to miss the issues that arise at their intersections.

Indeed, the true worst case scenario might be one where we don’t venture out from our safe harbors of knowledge to explore the more treacherous shores of uncertainty. As we do, we will need to be careful as well as bold as we map those shoals.

References

- S. Schneider, "The worst-case scenario", Nature, vol. 458, pp. 1104-1105, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/4581104a

- J.E. Hansen, "Scientific reticence and sea level rise", Environmental Research Letters, vol. 2, pp. 024002, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/2/2/024002

- K. Brysse, N. Oreskes, J. O’Reilly, and M. Oppenheimer, "Climate change prediction: Erring on the side of least drama?", Global Environmental Change, vol. 23, pp. 327-337, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.10.008

Nemesis @49 “I saw 10 fellow human beings at the table and 10 loafs of bread. Now 1 of these 10 fellow human beings took 9 loafs of bread and said “we have a problem, our house is overpopulated!” Now guess what happened next…boing poum tchak…”

Point well made, but 10 bliion people on the planet with some sort of fairer distribution of wealth, (and this is desirable) still pollute and consume, every one of them. It’s a huge load on the environment. Population is a problem. Full stop.

This is off topic so continue it on FR thread.

Al Bundy @46 as special kellog would say “use all the tools in the tool box”.

It is not just anthro climate forcing in isolation. Stipulate that a magic mechanism had subtracted all anthro forcing ever since say, homo habilis. Nevertheless, humankind would exert tremendous pressure on the environment even absent climate forcing.

So we must consider climate forcing as another stressor in addition to all our other impact. This is really difficult, since we are unaware of a majority of living things in even a teaspoonful of healthy soil. We burn away support from under our feet, we do not even care to name that we kill.

The combined impact is becoming evident on human timescale and living memory, people are waking up. The costs are dear, but one way or another, they must be paid.

sidd

I completely understand scientists desire to not say anything’s certain without 100% confidence. To err deep in the territory of caution. The very moment the even tiniest mistake, overestimation, underestimation, words spoken without extreme care, whatever, might occur, the professional denial industry leaps in an effort to undermine the entire science in the public mind. This creates an unrealistic expectation of perfection. Way more pressure, I suspect than for any other science, except perhaps evolution theory. Still, the more accurate the better. So in a way it could be argued that these people are performing a public service. Though, of course, that’s not their intention.

I wonder if anyone has compiled a list of mistakes in climate science and their subsequent editorial fixes to demonstrate that the scientists are indeed striving for honesty?

Al Bundy@46,

I find nothing in your comment that even indicates that you read mine. Are you just randomly typing?

Oh, Gavin?

https://themindunleashed.com/2018/11/mini-ice-age-nasa-scientist-sunspots-record-cold.html

The links seem mostly to go to pages associated with disaster preppers and nutrition supplements (sigh).

The very worst possible climate scenario could be hard to define precisely,given the complexity of the system. Perhaps there’s a possibility of run away warming that takes us someway towards Venus atmosphere. Perhaps the greatest presently unknown threats could be unforseen interactions between various processes and changes.

Having said that, we already know there are possible worst case scenarios that look very grim, and suggest the precautionary principle apply, so I’m not sure why a discovery of something even more catastrophic is going to do much more to motivate action to mitigate climate change. The problem looks like it’s people are not fully internalising and comprehending what we already know.

Some of the climate related problems are not easy to quantify, but are still very important to people, as in the following recent research. All this stuff adds together with the more tangible problems.

“One thousand ways to experience loss: A systematic analysis of climate-related intangible harm from around the world”

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959378018308276

“This is the case, for instance, for the symbolic and affective dimensions of culture and place, such as sense of belonging, personal and collective notions of identity, and ways of knowing and making sense of the world, all of which are already undermined by climate change. Here, we perform the first systematic comparative analysis of people-centered and place-specific experiences with climate-related harm to people’s values that are largely intangible and non-commensurable. ”

“We draw upon >100 published case studies from around the world to make visible and concrete what matters most to people and what is at stake in the context of climate-related hazards and impacts. We show that the same threats can produce vastly different outcomes, ranging from reversible damages to irreversible losses and anticipated future risks, across numerous value dimensions, for indigenous and non-indigenous families, communities, and countries at all levels of development. “

“The rise in atmospheric methane (CH4), which began in 2007, accelerated in the past four years. The growth has been worldwide, especially in the tropics and northern mid‐latitudes. With the rise has come a shift in the carbon isotope ratio of the methane. The causes of the rise are not fully understood, and may include increased emissions and perhaps a decline in the destruction of methane in the air. Methane’s increase since 2007 was not expected in future greenhouse gas scenarios compliant with the targets of the Paris Agreement, and if the increase continues at the same rates it may become very difficult to meet the Paris goals. There is now urgent need to reduce methane emissions, especially from the fossil fuel industry.”

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2018GB006009

https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/vbwpdb/the-climate-change-paper-so-depressing-its-sending-people-to-therapy?utm_source=vicefbuk

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2018JC014775

Unabated Bottom Water Warming and Freshening in the South Pacific Ocean

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2018JC014775

Ron R,

When discussing human nature “should” generally is a segue into a complaint about an irrefutable fact.

Steve Tubb,

The key is villainy. I once asked my biological “father” whether spending a hundred billion dollars saving tens of thousands of lives via the production of safer vehicles would be a better use for the money than slaughtering Others so as to maybe save more innocent lives on Our side than Our side loses in the slaughter?

He looked at me like I was crazy. Death and destruction aren’t terribly important to many folks unless there’s intent behind the factoid.

Paul Beckwith,

Excellent point. If you graph the trajectory of inaccuracy you could come up with an estimate of how inaccurate current estimates are.

Zebra,

The issue isn’t “give and take” but a refusal to engage play and imagination. I see the so-called debates. They’re about points and trades.

But even the ideal, when based on that system, is 50% stupid in this direction combined with 50% stupid in that direction.

Stupid is as stupid compromises. When the system is inadvertently designed to elevate stupid people and stupid ideas. You’d have to be stupid to expect brilliance

Radge,

Yeah. You grok it. Ever read “Stranger in a Strange Land”? Way relevant to today.

Larry G,

Yeah. Humans aren’t deer. When we see headlights we build an IED.

Phil Hayes,

Yep, the best is the enemy of the good and the GND would have benefitted from better grounding.

John Monroe,

Ysda yada yada. We’re partying like it was 1999. Get with the program, dude. ;-)

To all,

This thread is an example of what RC can be.

Congrats

John Monro,

You’ve never met a slumlord, eh? Insurance is often for the best case scenario….

….and giving the best case a nudge can be fun.

John Monro,

The working class lives an uninsured life. Yet I don’t see any of the stuff you claim should result. As if more than two old bitties in the apt complex I live in have a fire extinguisher.

You are anthroanthromorphizing

John Monro,

The rich insure, the poor endure.

Plug that dynamic into the climate equation (and remember to include the fossil fuel reserves and infrastructure bubble)…

…and see what pops

For some reason worst case scenarios are used regularly everywhere we want people to change their behaviour. Consider the campaigns against smoking or drunk driving. Fear is used as a motivator in pretty much anything with negative consequences, from drug use to nuclear proliferation. Yet global warming is always seen as the exception to this. Why is that?

It’s not important whether “fear-based messaging” is effective or not. The purpose of articles and comments on this blog is to make cogent comments about the current state of climate science. News lately has been worse than IPCC projections in many areas, and most of the public doesn’t even know much about altered ocean circulation, Arctic melt and tundra burp surprises, and many other reinforcing feedback loops.

Scientists should not censor or play down scary information. It needs to get out to the public. More of us need to find a way to accomplish that goal, including calling most “green” NGO’s and “liberal” media platforms to account.

Worst case scenarios help us to better understand the problem, the art of it is to stay focused, and not to give in too much to the fantasies. However, there are also “surprises” when it comes to species extinctions (insects, fish etc), and you cannot discard scenarios, only because they might take hundreds or thousands of years to establish.

Facts. We are out of the realm of the known, faster than PETM, more like in the middle of a large impact event and natural abrupt climate change. Imho, some worst case scenarios will establish itself, maybe due to influence on the human psyche, or through interconnectedness. The problem with general science is that it requires evidence, but in our situation, by the time we get that to a point of established knowledge, we are already are well in the middle of a catastrophe. Hence, precautionary principle applies.

So I would not discard methane scenarios and similar, because honestly the debunking is not convincing enough. What if there is another Storegga Slide event? And because you can not be 100 percent sure that you are correct. You can say that time scales are off, or that there are unknowns and so on, but eventually we will get some very nasty situations from a global perspective.

To be more precise, look at Hurricane Harvey’s rain fall amounts, it surprised researchers who study this. Ozone holes over major cities, surprised researchers. Thermokarst formation and the progress of thawing, surprised researchers…

It all comes down to, if we can survive this as a species.

@Steve, #62

“Fear is used as a motivator in pretty much anything with negative consequences, from drug use to nuclear proliferation.”

Exactly. Fear is essential in the struggle for survival. An animal (or a man) without fear is a dead animal, a species without fear is a dead species. Fear acts like a warning sign. When I realize my house is burning down, then I’m in fear, only psychopaths would have no fear.

Where is the fear? Capitalism does not like fear when it comes to climate heating, because climate heating questions capitalism in total. It is getting more and ever more obvious by the minute:

The system can not go on the way it used to go, but that’s bad for the established economy and the modern myth of everlasting and evergrowing consumerism. Capitalism does not like fear of climate heating, because it’s bad for consumerism and therefore bad for capitalism. Fatal.

66 Steve says: “Why is that?”

A lack of knowledge and very poor judgment by those with a public presence that has broad appeal. With a dose of the Dunning-Kruger effect – the assumption that a high intelligence and education level combined with an expertise in one arena presupposes a very high level of expertise in every other arena.

Concern about the worst case seems to be something of a red herring. In the worst case we are all dead after all. Just like in the best case nothing of any negative consequence happens.

What I and the rest of the public want to know is how bad is the most likely case going to be. Everyone I know studying climate science is certain that we are heading to a 4 deg world, and that no, a magic pixie dust technology that can remove gigatonnes of CO2 will not come to save us at the last minute. As such, I’d rather be hearing realistic analysis of agriculture, fresh water, soil, storms, and so on in a 4 deg world, rather than endless feel good studies that pretend we can keep warming below 1.5 deg.

Ray,

I read your comment and stand by my point. Scientists tend to think that standoffishness contemplation and first officer Spock reactions, “fascinating”, and caveated conversation is the only ” proper” way.

I’m sure I’m not conveying my point as well as I should (my mind is elsewhere at the moment) but that you missed my point, whether my point rules or drools, reinforces my point.

Scientists tend to be stuck up. And no, the way they’ve chosen is not the be-all and end-all for all situations.

Like now, for example. How effective have climate scientists been over the last four decades? 3%?

“Not my job” is a lame excuse when one’s job is stupidly defined.

Ray,

Remember when unions committed suicide? They took “not my job” to heart. A worker standing next to a leaking valve that WILL blow up the facility should NOT close the valve because it’s not his job??!

Timely and relevant to this discussion; David Wallace Wells was interviewed on Amanpour & Company a few days ago. I think Amanpour did a pretty good job:

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/amanpour-and-company/video/david-wallace-wells-severity-climate-change-ot0rdx/

Re the reference Christiane made to Greta Thunberg… this clip:

https://www.pbs.org/video/16-year-old-climate-activist-greta-thunberg-cayhpt/

—-

Kudos to AOC for making climate a thing in party politics. General reaction of party hacks, “Huh? Wha? You can actually do that?”

Just putting it out there.

Ray,

An example:

Scientists constrained thermal expansion of the oceans decades ago and also knew that melt was unconstrained. So they did the most counterproductive thing imaginable:

Let’s set melt to zero and put an asterisk next to the number so everybody will (well, important people, you know, scientists), everybody will comprehend that that’s a stub.

FAIL!

Then there’s the fact that little kids are outperforming the lot of you scientists. WTF aren’t you guys on the picket lines with the kids. As if a sea of white coats wouldn’t be way more valuable than playing with test tubes.

Steve @66 says “Fear is used as a motivator in pretty much anything with negative consequences, from drug use to nuclear proliferation. Yet global warming is always seen as the exception to this. Why is that?”

Good comment. Probably several reasons. One reason for scepticism about using fear might be the climate denialists keep telling us fear wont work. Frankly I’m not too impressed with anything they say.

Part of the problem with discussion of worst case scenarios is complexity. At the risk of sounding trite, climate models model climate. Human responses to climate change are only included in the models as a simple variable (crudely: if we reduce GHG emissions at x rate per annum, we can expect y outcome in terms of warming by 2100). What exactly being on this trajectory means for society at any given point on the trajectory and how it modifies x is not what climatologists do, and is not knowledge in the same way that the outputs from a climate modelling exercise are. We know what has happened to date in terms of GHG emissions, and based on this knowledge we know that we are much closer to worse case scenarios than we were 20 years ago. The clear implication is that we need systemic changes to how our society is organised, and that these changes need to happen urgently because our current trajectory is unsustainable. What worries me with the rise of right-wing nationalism in the USA and elsewhere is the risk that the socio-economic stress of climate change is already precipitating a downward spiral of maladaptation. Let’s hope that leaders like AOC and ideas like the Green New Deal can arrest and reverse this.

“To get to the worst cases, two things have to happen – we have to be incredibly stupid and incredibly unlucky. ” Well we’ve already been incredibly stupid, so that means we only have to get incredibly unlucky….

A number of brief points:

1. Science is set up to incentivize publishing papers that turn out to be true (of course). In fact, a scientist has to be quite certain of something before publishing. See Comment 19 about Type 1 and Type 2 errors. This is fine for subjects like Black Holes, but not so good for issues that threaten human civilization. So you might publish that SLR will be 3 feet within a certain time if you are 95% certain, but will not publish about it being 10 feet, if you are only 50% certain. If the military worked this way, they would lose every battle they fought.

2. Fear is not just a motivator, it is the #1 motivator! As others have pointed out, conservatives use (often fake) fear to motivate their constituents to great effect. You see it in the news every day. How can we deny it works? To put it another way… how can we possibly solve a problem if we are not honest about what the impacts of the problem may be?

3. Civilization is a complex system. A subset of civilization, the economy, is also a complex system. We saw what happened when we had a problem with sub-prime mortgages and how that one minor thing screwed up the economic system. Climate change will screw up many of the interconnected pieces of civilization simultaneously.

4. Worst case is probably run-away warming leading to Venus-like conditions that extinguish all life on Earth. OK, we can agree that the worst case is low probability. But a still-bad case is the collapse of civilization, which we seem quite on track for. We are headed for +4ºC warming (unless civilization collapses first) and that may very well lead to +6ºC warming (or, with the recent cloud study, +12ºC). The last time the Earth hit +6ºC, 90% of life on Earth perished. That experiment has already been run. Why do we think it does not apply to us?

Al Bundy,

Dude, have you ever even known a scientist? Because your description does not match the reality I have come to know over my ~40 years in physics. In terms of personality, scientists run the gamut–and far from being “Spock-like,” they are passionate about what they do.

What is more, your criticism of scientists is unjustified–because the most consistent voices in this struggle have always been scientists. Unfortunately, what you are demanding of scientists is not something science, by itself, can give. It was never designed to dictate policy. Its purpose is to increase understanding, and so at most it can inform policy and policy makers. It is up to the policy makers to implement policy.

The one thing scientists bring to the table is their reputation as truth tellers–and part of the truth is uncertainty. If scientists pretend their conclusions are more certain than they are; if they shade the truth; if they push particular policies as “the only solution”, they lose that advantage, because in that moment they cease to be scientists.

So, by all means, scientists should alert the public to the threats their research shows. They should warn the politicians of the serious and unnecessary risks they are taking. They should alert the larger community to potential solutions. Indeed, they are already doing this. What they cannot do is put their thumbs on the scales, ignore uncertainties and pretend perfect knowledge.

It is the citizens who must have the courage to embrace the understanding that science gives and pressure the policy makers to implement policies based on that understanding. When a scientist does this he or she is acting as a citizen, not a scientist. They are speaking ex-cathedra.

What they absolutely should not do is listen to an ignoramus such as you who has not understanding of science, of politics or human nature. They should feel quite free to ignore you–because your ignorance will only get in the way of a solution.

#71 Steve,

But how precise do the realistic assessments have to be?

I agree that we are likely to experience an energy increase in the climate system that will manifest as a GMST in the range you suggest, at least.

Then what? Predictions by zip code of rainfall, or heatwaves, or agricultural failure, and so on?

At best we will get some regional projections, and we don’t really need super-skillful models to know that only a few regions will experience “positive changes”; mostly it will be very disruptive.

As others have pointed out, we are dealing with the intersection of the climate system with the human socioeconomic/geopolitical system. The most likely result is disruption plus, I think. Very plus.

Worse case is that:

worsening climate + worsening of other independent variables (political, environmental…) = run-away stupidity

Radge Havers: “Worse case is that:

worsening climate + worsening of other independent variables (political, environmental…) = run-away stupidity”

Aw Batshit! We’re there!

Gavin, with respect, I do not agree that reticence is not a problem in climate science (and other areas of science as well), though some scientists are less reticent than others. I do agree with those above who have suggested that scientists could take a cue from engineers. I have tried to explain this view in a recent paper in Ethics, Policy, and Environment 21(2), 2018: https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.uleth.ca/doi/full/10.1080/21550085.2018.1509483.

The problem is partly ethical, partly methodological. Short version: climate scientists are presently faced with the same problem that medical doctors and engineers have been faced with for centuries, which is to make decisions or offer concrete advice on life-or-death matters in real time, under conditions of uncertainty. Research scientists are trained to withhold judgement until the highest feasible level of certainty has been reached (thus, for instance, no one got a Nobel for the Higgs boson until it was confirmed to seven sigma). Doctors and engineers, by contrast, all too often have to make decisions without what Hansen called “the comfort of waiting for incontrovertible confirmations.” That is why their decisions tend to be as conservative as possible, consistent with the necessity of actually solving the given problem.

Very smart people can disagree about the probability of such extreme outcomes as the near-term collapse of WAIS, widespread oceanic euxinia, or a methane belch. What we can be certain about, though, is that humanity is presently engineering the conditions that make such outcomes more probable, as well as many other somewhat more likely but still very deleterious outcomes. The fact that extreme outcomes of global carbonization are increasingly probable but still probably preventable needs to be front and center in public discourse, and only the relevantly qualified scientists can put it there. They must be willing to take the intellectual risks entailed in doing so.

Accredited professionals have a legally defined duty to report and to inform the public. Research scientists can’t be legally compelled to blow whistles in the way that engineers can, but they may well feel a similar sense of moral obligation.

Hansen again: “We may come to rue reticence if it serves to lock in future disasters.” Erring on the side of least drama could in the end amount to erring on the side of much more drama than anyone would care to experience.

[Response: I’ll read your paper, but I don’t disagree that reticence or ESLD should be avoided, my argument was that there isn’t much in the way of convincing evidence that they are important. – gavin]

Rachel Carson saw the worst case and wrote about it, just in time. Where were the scientists then? Don’t be complacent. I have watched the scientists for thirty years and found that there is a consistent underestimate in severity, consequence , and severity over time. Call me pessimistic or pragmatic but I am not sanguine about the accuracy of scientific projections.

49: “I saw 10 fellow human beings at the table and 10 loafs of bread. Now 1 of these 10 fellow human beings took 9 loafs of bread and said “we have a problem, our house is overpopulated!” Now guess what happened next…”

How did the other 9 stop the 10th from taking more than their fair share?

How do you propose that we stop people in the privileged West from consuming more than their fair share of resources?

This is what it comes down too, you can pinpoint the core issues very simply, but I’ve yet to see a realistic practical solution, which is probably why humanity as a whole has done three fifths of bugger all over the last century in addressing anthropogenic climate change and resource consumption/depletion.

Re 69 the post inadvertently summed up a lot of the problem. The alarm about warming is too often monopolized by people with extreme political agendas. The repeated use of the word capitalism says it all. To get the public onside the campaign has to be more mainstream.

DP@87,

Unfortunately, capitalists by and large have contributed to this situation by denying the climate crisis rather than embracing it for the opportunity it really is. If you see a group that feels they must deny the incontrovertible facts to assert their ideology, it undermines your confidence in their ability to take effective action.

The best way for capitalists to make the movement more mainstream–and more profitable for them–is to come up with solutions.

Let stay positive and treat the environment around us just like we treat ourselves.

@Adam Lea, #86

” How do you propose that we stop people in the privileged West from consuming more than their fair share of resources?

This is what it comes down too, you can pinpoint the core issues very simply, but I’ve yet to see a realistic practical solution, which is probably why humanity as a whole has done three fifths of bugger all over the last century in addressing anthropogenic climate change and resource consumption/depletion.”

Well, I stayed away from overconsumption all my life and I did not procreate. The less I need the more I am free :) See, I take my personal responsibility very serious. If everyone would do that, the world would look very different. Beyond that, I can’t change the greed and ignorance of others, I can’t even change my neighbour. Everyone is responsible for his very own actions, that’s Karma. The wealthy folks don’t change, they grab whatever they can. Bad luck for them too :)

DP says: “The alarm about warming is too often monopolized by people with extreme political agendas. The repeated use of the word capitalism says it all. To get the public onside the campaign has to be more mainstream.”

The extremists do talk a lot about capitalism. They are also always hammering away about fossil fuels or even on the amorphous global economy. What the hell is that?

It gets old, does it not? It’s just like the worst case scenario discussion, hammering on about these things just turns people off. Why can’t we discuss climate change and the possible outcomes without talking about capitalism, fossil fuels and the global economy. There would be a lot less drama if we would just make these simple adjustments.

Thanks for helping with that!

Mike

DP:

To be fair, the author of #69 doesn’t think of himself as mainstream either. Regardless, it’s true that tragedies of the Commons, including climate change due to anthropogenic global warming, are consequences of ‘free market’ capitalism. That’s because without collective intervention, buyers and sellers on the ‘free’ (of collective intervention) market will jointly externalize every cost they can get away with. OTOH, from that perspective a careful nudge from the ‘visible hand’ of government in the form of a carbon tax, such as Carbon Fee and Dividend with Border Adjustment Tariff, should (in the predictive sense) direct the market toward a carbon-neutral energy economy at the lowest net cost. A version of CF&D-BAT has been introduced in the US House of Representatives as H.R. 763, the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act. As a narrower, more mainstream (we pay taxes already) decarbonization proposal, something like it should (again, in the predictive sense) be easier for the US to enact than a complete overhaul of national economic policies. That’s not, of course, to say CF&D-BAT will be all that easy! Caveat: I am neither an economist nor a politician by profession.

I’m obliged to redirect any followups to the Forced Responses thread.

87 DP says:

6 Mar 2019 at 2:13 PM

Re 69 the post inadvertently summed up a lot of the problem. The alarm about warming is too often monopolized by people with extreme political agendas. The repeated use of the word capitalism says it all. To get the public onside the campaign has to be more mainstream.

—

Only in the USA. The rest of the world 6.7 billion are more rational and balanced and far to the Left of the USA mainstream “world views”. The sooner the USA joins the rest of the world where reality resides the better. But do not hold your breath. I find it really humorous how so many people in the USA who see themselves as “liberals/progressives” are in fact nothing of the sort.

@mike, #91

” The extremists do talk a lot about capitalism. They are also always hammering away about fossil fuels or even on the amorphous global economy. What the hell is that?

It gets old, does it not? It’s just like the worst case scenario discussion, hammering on about these things just turns people off. Why can’t we discuss climate change and the possible outcomes without talking about capitalism, fossil fuels and the global economy. There would be a lot less drama if we would just make these simple adjustments.

Thanks for helping with that!”

LMAO, yeah, let’s get rid of discussions about the economy resp capitalism and fossil fools. Climate heating has nothing to do with the economy and fossil fools. Just let the people make money, money is neutral, it is way above the mundane world, so capitalism will never be affected by climate heating anyway, hehe 8) Hehe, harr harr 8))

Hi Kent re your post #84, I agree with you that scientists could learn from engineers. Engineering is based on how things work in practice, not on how they work in theory.

But I was unable to read your paper because the URL you gave is for your university proxy. I have found the paper now, but only the abstract is outside a paywall. If you add your paper to your ResearchGate publication list then it would be possible for me, and other independent researchers who cannot afford $30 a time for each interesting paper, to request a preprint from you. In the meantime, I am showing what I have discovered regarding it:

Peacock, K. A. (2018) ‘A Different Kind of Rigor: What Climate Scientists Can Learn from Emergency Room Doctors’, Ethics, Policy & Environment, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 194–214 [Online]. DOI: 10.1080/21550085.2018.1509483.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21550085.2018.1509483

ABSTRACT

James Hansen and others have argued that climate scientists are often reluctant to speak out about extreme outcomes of anthropogenic carbonization. According to Hansen, such reticence lessens the chance of effective responses to these threats. With the collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) as a case study, reasons for scientific reticence are reviewed. The challenges faced by scientists in finding the right balance between reticence and speaking out are both ethical and methodological. Scientists need a framework within which to find this balance. Such a framework can be found in the long-established practices of professional ethics.

Tom Lehrer on worst case scenario: “Always predict the worst and you’ll be hailed as a prophet.” Lehrer attributes this line to a friend.

Peacock 2018 (full pre-print):

http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/13428/1/Scientific%20Reticence%20Preprint.pdf

The issue here is what climate models predict, concerning temperature and ocean levels, concerning what will happen several decades out if CO2 admissions continue to increase. What happens when the model parameters are adjusted? If there is no clear result with this modeling, the worse case scenario is anybody’s guess, and commentators are justified in worrying about a likely horrible worse case scenario.

The problem is worsened by the fact that there is a several-decade time lag between greenhouse gas increases and temperature increases, and between temperature increases and ocean level rising. It is easy to show that with regression analysis. The interactions and feedbacks, especially between ocean CO2, ocean temperature at different depths, and atmosphere temperature and CO2, take a long time to play out. If there are strong positive feedbacks, change is exponential over the long haul, which means a horrible worse case scenario.

Here ya go:

http://www.lifeworth.com/deepadaptation.pdf

Although making many valid arguments, I think Gavin is missing some very important points.

1) The Man-made release of greenhouse gases is – as far as we know – happening at a speed never before experienced on Earth. For example it’s going at least fifteen times faster than when siberian volcanic eruptions created enormous burning of hydrocarbons in sediments before the end-permian extinction event 252 million years ago – the worst extinction event we know. Consequently also the temperature rise is probably much faster than in any known natural events so far.

Therefore we can’t rule out that things will happen that has never before happened in periods of natural releases of greenhouse gases and natural warming of the globe. Collapse of ecosystems at hitherto unknown scales and with hitherto unknown catastrophic consequences are possible. And it is probably impossible to calculate the odds of such events occuring – because we have no examples from the paleoclimatology.

2) Even if we confine our scope to natural events of rapid climate change in the most well-known past, we must recognize that the whole human civilization has developed during a very short timespan with extremely stable conditions compared to these events in the paleoclimatic. Especially the industrial capitalism and its burning of fossil hydrocarbons has developed at its current speed and global scale, and the rapid rises of atmospheric CO2 content and global temperatures, has only been going on for less than around the last fifty years.

This study http://science.sciencemag.org/content/321/5889/680 show that big parts of the global atmospheric circulation was rearranged in just a few years around 12 ky BP. Noone can doubt that if something like that should happen today, the consequences for the global agriculture and societies would be catastrophic. Imagine fx a major shift in the monsoon system. I think even something much less dramatic than that could lead to enormous and chaotic developments in the global economy and social conflicts and wars on a very dangerous scale.

Our current global “market” economy is what in physics is called a metastable system: even small instabilities are self-enhancing. Just look at what happened during the socalled financial crisis 2008 or during older economic periods of depression. Modern society is very complicated and very vulnerable, especially with respect to its ecological basis. Mankind is fx now using more than fifty percent of the global photosynthetic product. Which is an enormous stress on ecosystems in itself with consequences like “insectageddon” that are just beginning to emerge.

Of course it does not help anyone to panic. But to say that we can just carry on more or less with business as usual, as is the message from the current “scientific consensus” as expressed fx by the IPCC “summary for policymakers” etc. is completely irresponsible. All experience shows that the socalled “optimism” proclaimed by almost everyone in the last few decades has led to absolutely nothing else than further exploding emissions so far. It has been and is a sleeping pill.

“There is a widespread inclination to think of climate change as a form of compound payback for two centuries of industrial capitalism. But among Wallace-Wells’s most bracing revelations is how recent the bulk of the destruction has been, how sickeningly fast its results. *Most of the real damage, in fact, has taken place in the time since the reality of climate change became known. And we are not slowing down. One of the sentences I found most upsetting in this book composed almost exclusively of upsetting sentences: “We are now burning 80% more coal than we were just in the year 2000.”*

There’s also a temptation, when thinking about climate change, to focus on denialism as the villain of the piece. *The bigger problem, Wallace-Wells points out, is the much vaster number of people (and governments) who acknowledge the true scale of the problem, and still act as if it’s not happening*.” (My *’s, KJ).