2017 is set to be one of warmest years on record. Gavin has been making regular forecasts of where 2017 will end up, and it is now set to be #2 or #3 in the list of hottest years:

With update thru September, ~80% chance of 2017 being 2nd warmest yr in the GISTEMP analysis (~20% for 3rd warmest). pic.twitter.com/k3CEM9rGHY

— Gavin Schmidt (@ClimateOfGavin) October 17, 2017

In either case it will be the warmest year on record that was not boosted by El Niño. I’ve been asked several times whether that is surprising. After all, the El Niño event, which pushed up the 2016 temperature, is well behind us. El Niño conditions prevailed in the tropical Pacific from October 2014 throughout 2015 and in the first half of 2016, giving way to a cold La Niña event in the latter half of 2016. (Note that global temperature lags El Niño variations by several months so this La Niña should have cooled 2017.)

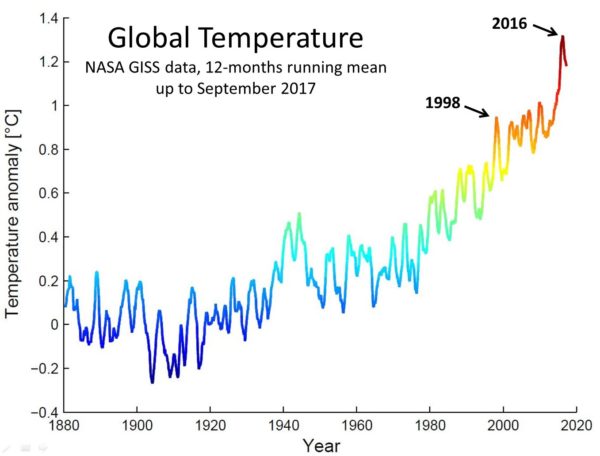

The hot El Niño year of 1998 is comparable to 2016, since both years followed the two hitherto strongest El Niño events. And 1998 was followed by a cool 1999, only ranked #7 in the list of hottest years until then. So here is a comparison of 1998 versus 2016. Let us first look at the full time series of GISTEMP global temperature data, see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 GISTEMP global temperature data, in 12-months running average (anomalies relative to the first 30 years). The data are available monthly and averaging over 12 months removes a considerable amount of month-to-month ‘noise’. Showing only calendar-year averages would lose some information – e.g. it would only fully show peaks in temperature if by chance the maxima aligned with the calendar year.

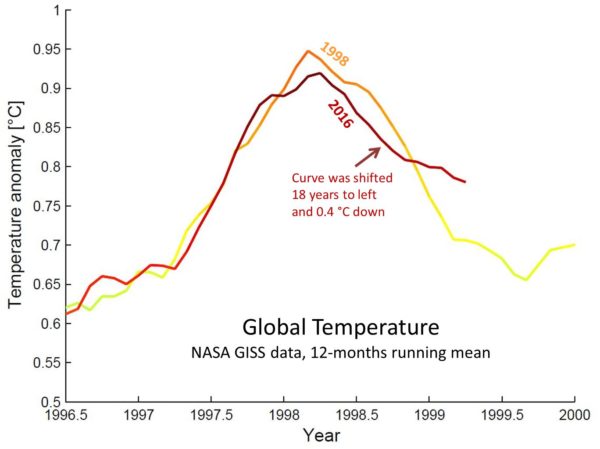

The El Niño peaks in 1998 and 2016 are clearly seen. It has been shown in several studies (e.g. Foster and Rahmstorf 2011) that El Niño is one of the main causes – perhaps the main cause – of short-term variability in global temperature. The following graph overlays those 2 El Niño peaks by shifting the 2016 peak back in time by 18 years and down by 0.4 °C.

Fig. 2 The two El Niño peaks in global temperature from Fig. 1, zoomed in and overlayed by shifting the 2016 peak back in time by 14 years and down by 0.4 °C. The darker red curve is the 2016 peak, as in Fig. 1.

The two peaks align very well. The first conclusion is that global temperature evolution over the last few years is very similar to that around 1998 – except the Earth is now 0.4 °C hotter. That’s 0.4 °C warming over 18 years, corresponding to 0.22 °C per decade – a bit more than expected from the long-term global warming trend since 1980, which is 0.17 °C per decade in the GISTEMP data. (So much for the “no warming since 1998” meme so popular with climate deniers.)

The second observation is that initially temperatures climbed down from the peak as fast as in 1998 – but then the cooling slowed down, and the last 12 months haven’t just been 0.4 °C warmer than in 98/99 but closer to 0.5 °C warmer. So it is clear that our planet is not cooling off as fast as after the 1998 El Niño peak. I wouldn’t over-interpret this – we’re looking at a really short interval here, so it is clearly no reason to diagnose a noteworthy acceleration of global warming. But there certainly is no sign of global warming slowing down. It will be interesting to watch how this continues over the next months; the ENSO forecast is for developing La Niña conditions again this coming fall/winter.

Stefan,

“we’re looking at a really short interval here, so it is clearly no reason to diagnose a noteworthy acceleration of global warming.”

I would tend to say, that there is a jump, on a physical way, the climate system is interacting with antropogenic Forcing, i think sometimes in a non linear way, this view can be supported if you looking at the ocean temperature in the first 100 meters: https://data.nodc.noaa.gov/woa/DATA_ANALYSIS/3M_HEAT_CONTENT/DATA/basin/yearly_mt/T-dC-w0-100m.dat

for latest data:

https://data.nodc.noaa.gov/woa/DATA_ANALYSIS/3M_HEAT_CONTENT/DATA/basin/3month_mt/T-dC-w0-100m4-6.dat

You see clearly the difference between 1998/1999 to 2016/2017. On the other Hand, this layer is the most important one, because of atmosphere-ocean-interactions due the mixing layer. If you would correct 2017 by MEI-Index you would get the the warmest year and strongest year to year increase.

So where it come from? My opinion:

Because since 1998 energy was stored in lower ocean layers (below 100m) because of more upwelling, same time, the first 100m gets relativ cool compared to forcing, since 2015, upwelling has brocken down and first 100m aprupt adjust to forcing, so why its warmer now then after 1998, is possibly because before the event, the relativ imbalance in the first 100m was stronger then in 1997

Greets

“we’re looking at a really short interval here, so it is clearly no reason to diagnose a noteworthy acceleration of global warming.”

I agree, fwiw. The 1998/1999 peak, rebound, and recovery to a higher level was about 5 years in duration. This could be like that.

I think a large part of what’s going on has to do with Arctic amplification. The normal seasonal cycle of Arctic amplification is coincidentally basically the same as for the global average response to El Nino, even though the Arctic warming is probably at least partly independent of El Nino. And as we get further from the baseline that seasonal cycle becomes more exaggerated.

That means the 2016 El Nino response maybe looks stronger than it really was. If you make the same comparison as above but look at GISS cropped to 90S-60N, the 2016 event peaks significantly lower than 1998, and is closer to the less strong 1988 event. A number of other indicators also suggest that 2016 wasn’t as severe as 1998 or 1983, belonging to a lower class of merely very strong events.

Likewise, the 12-month running mean probably hasn’t gone down as much in 2017 because very strong Arctic warmth persisted during the first few months of this year.

The other large contribution to year-on-year variability of the global mean temperature is the winter weather in Siberia and Canada. This is a large area with very large variability due to random weather on short time scales, which even averaged out over a year gives s sizeable contribution. And yes, it was very warm there the 12 months.

The question that arises is whether El Ninos are increasing in frequency with increasing ocean temperatures. Is there any significant statistical relationship?

0,4/1.8= 0,222222222 /decade.

‘I am surprized.

S.K.

But, Hr Stefan

I lack a proper discussion also of the minimals along the curve. This hunting for Guinness records may often overshadow the negative side of the curve.

There has been a gtremendous rain in Southern Norway last month, car doors and Windows 3 times under water, beat that! When will People learn? And we are pumping water in the cellar again. Hamburg had it even worse. “Hochwasser” they Call it.

S.K.

Alas – nothing learned from dealing with deniers. Above Fig. 2 will be ‘cited’ up and down by deniers that 1998 truly had been warmer than 2016 – see, even realclimate says so!!11!1 You could have included the 0,4 degree thingy a gazillion times more to no avail. Unforced error, I would say…

[Response: It is why I put it in the figure and not just the caption. -stefan]

Oops – I could have sworn that part wasn’t there when I made the comment…

It is why I put it in the figure…

Stefan, meet PhotoShop. PhotoShop, meet Stefan.

There are people out there who will gladly mask out that detail and still claim it came from RealClimate!

#8 and #10

Agree; I understand the need for the 18-year leftward shift – but shape of the curves could still be compared without the 0.4 degree downward shift in the 2016 curve.

Bob Loblaw: Wonderful! Deniers photoshopping the figure would discredit them as dishonest (as if they needed further discrediting) in the eyes of people still not totally brainwashed.

This is really interesting. How can I get a synopsis of this article for consumption by our students at the Institute for Climate Change and Adaptation in the University of Nairobi? I’d also like to see the projected impacts for East Africa

The article is open access – see the reference above.

One thing. According to the ENSO chart the La Nina that followed the El Nino in late 2016 was very mild and was in fact within the accepted neutral zone of + or – half a degree C. So it shouldn’t have had much of an effect. Though the warming in the first half of 2017 is a mystery, NASA/GISS showing anomalies of more than 1C in some months.

You are right about your picks for warmest years only if you include theEl Nino peaks as permanent temperature. They are temporay structures that stand over the real temperature line. The 2016 El Nino is a clearly an abnormality that stands higher than the super El Nino of 1998 does. And that super El Nino itself is an abnormality because it distorts the serial Ef Ninos in the eighties and nineties. There were five of them in a row, all erssentially the same height. The 1998 El Nino came in with twice the height of its five predecessors. It was also in a hurry – it came and left within a three-year period. Furthermore, it left a chunk of its warm water behind that created the warn hump at the beginning of the 21st century. Its peak in 2002 was 0.4 degrees higher than the mean temperature of theEl Ninos that preceded the 1998 El Nino. That chunk of warm water started to cool after 2002. In ten years, vrom 2002 to 2012, global temperature went down by 0.2 degrees Celsius. Beyond that the temperature begins to rise because of the buildup to 2016 El Nino has started. If the 1998 El Nino was clearly an abnormality at the time. The 2016 El Nino is even more of an abnormality judging by its height. We need to find the source of these abnormalities and it must involve the process by which El Ninos are created. Peak height relates to the amount of warm water each El Nino was able to bring to the coastal environs at the latitude of California and above. First, all the warm water of all the El Ninos that exist comes from the equatorial currents whipped up by the trade winds in the Pacific. The amalgamated currents hit the east coast of New Guinea and split np north and south along the coast. Each branch ends up creatng an elevated platform called a warm pool at its terminus. On the north side of the equator it is called the Indo-Pacific warm pool, alleged to contain the warmest water on earth. On the south side of the equator it us a warm pool in the Solomons where tthe Japanese attempt to grab Australia was stopped at Guadalcanal, But there is a limit to how much water you can pile up into a warm pool. When that limit is reached the flow reverses itself because of granity. It so happens that the beginning of the equatorial countercurrent is where the trade currents came ashore. Thr back flow from thhe lndo-Pacjfjc warm pool is now carried across the ocean by the equatorial countercurrent and runs ashore in South America. There it is divided again into north and south flowing streasns. The north-flowing segment spreads out in front of the West Ciast near California. Its warm water creates a mass of warm moist air by evaporation. And this is just wha the Westerlies that blow in from the ocean need to create an El Nino. They cross the continent and the ocean beyond it to spread El Ninos all over the world. This does not happen in the southern hemisphere because the High Andies are in the way, I have assumed that the warm water source for El Ninos came from the Indo-Pacific warm pool but this is by no means certain, It is conceivabke that the southerb\n warm pool just may occasionally contribute to El Nino zize by contributing additional warm water. Like for the 1998 super El Nono and the giant 2016 El Nino. Its peak height almost dictates this. And when you examine the structure if that peak in UAH satellite data it almist looks like there is a buried peak on its right side that just may be the cause of its unusual peak height. All this will dissipate, If you extrapolate the short segment from 2002 40 2012 you end up guessing tha t maybe, next year ,sometime the real ground temoerature will be smilar to what it was in the eighties and nineyies.

Arno Arrak, #16, I didn’t read that carefully, but the blah blah blah seemed to contain stuff about cooling and a lot of hand-waving. Do you have a prediction for global surface temps different from the scientific mainstream, which tells us to expect just about every decade to be warmer than the last, absent really large volcanic eruptions? I keep offering a substantial bet on the subject, but I never get any takers.