How has global sea level changed in the past millennia? And how will it change in this century and in the coming millennia? What part do humans play? Several new papers provide new insights.

2500 years of past sea level variations

This week, a paper will appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) with the first global statistical analysis of numerous individual studies of the history of sea level over the last 2500 years (Kopp et al. 2016 – I am one of the authors). Such data on past sea level changes before the start of tide gauge measurements can be obtained from drill cores in coastal sediments. By now there are enough local data curves from different parts of the world to create a global sea level curve.

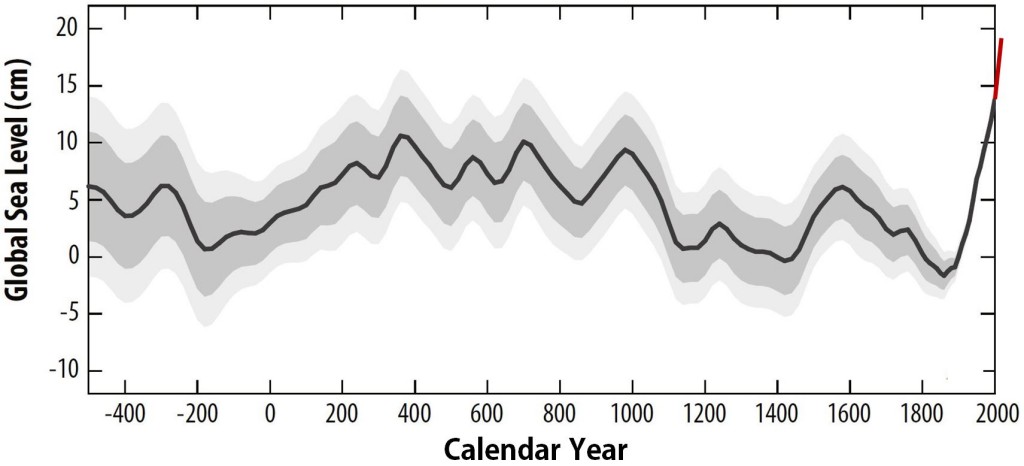

Let’s right away look at the main result. The new global sea level history looks like this:

Fig. 1 Reconstruction of the global sea-level evolution based on proxy data from different parts of the world. The red line at the end (not included in the paper) illustrates the further global increase since 2000 by 5-6 cm from satellite data.

To understand this curve we need to know one thing. There is a remaining uncertainty in the linear trend over the whole period. This is because in many places of the world slow processes, especially continuing land uplift or subsidence after the end of the last Ice Age, cause a sea-level trend uncertainty (because land subsidence is not the same as sea level rise, this needs to be subtracted). It is therefore the fluctuations around the linear trend which are the most robust aspect of these data. The uncertainty in the trend is small, only 0.2 mm/year (the current sea level rise is 3 mm/year). But even a small steady trend of 0.2 mm/year amounts to half a meter during 2500 years. For the graph above, this means that the correct curve could be “tilted” a little to the left or right. This would, for example, change the relative global sea level in 2000 compared to the Middle Ages – this relative height does not belong to the robust results, as stated in the paper.

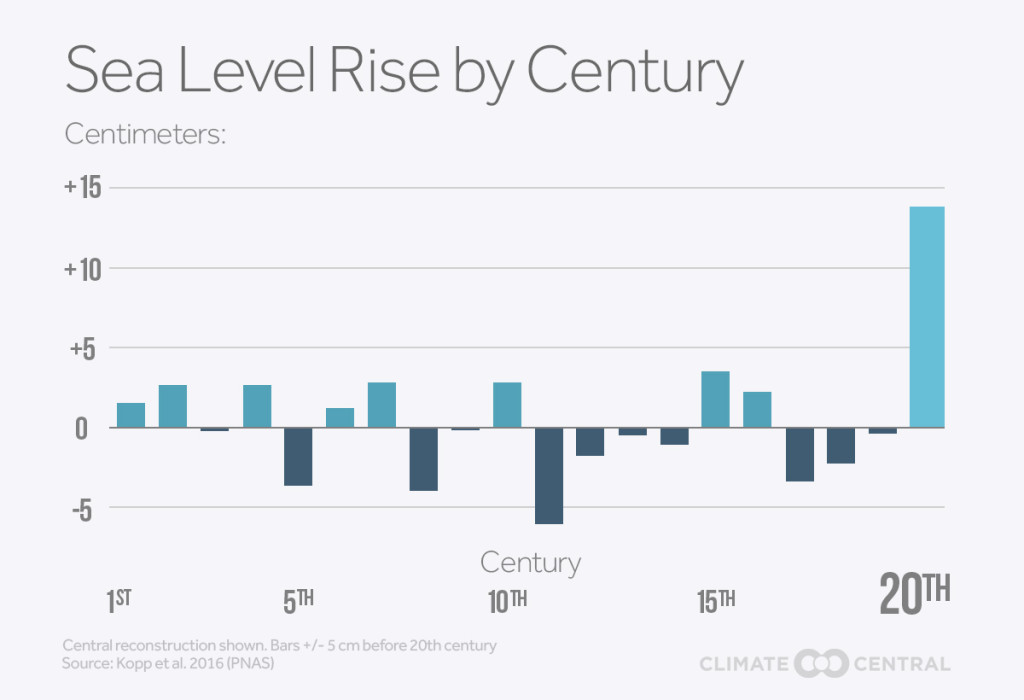

In contrast, a robust result is the fact that sea level has risen more during the 20th century than during any previous century. (This statement is true regardless of an additive trend.) A good way to show this is the following graph.

Fig. 2 Sea-level change during each of the twenty centuries of the Common Era (Graph: Climate Central.)

The fact that the rise in the 20th century is so large is a logical physical consequence of man-made global warming. This is melting continental ice and thus adds extra water to the oceans. In addition, as the sea water warms up it expands. (A new study has also just been published about the size of individual contributions derived from satellite data: Rietbroek et al 2016).

The paleoclimatic data reaching back for millennia can be used to better separate the natural variations in sea level and the human impact. With near-certainty at least half of the rise in the 20th century is caused by humans; possibly all of it. From natural causes alone sea level might also have fallen in the 20th century, instead of the observed rise by close to 15 centimeters.

What will happen in the 21st century?

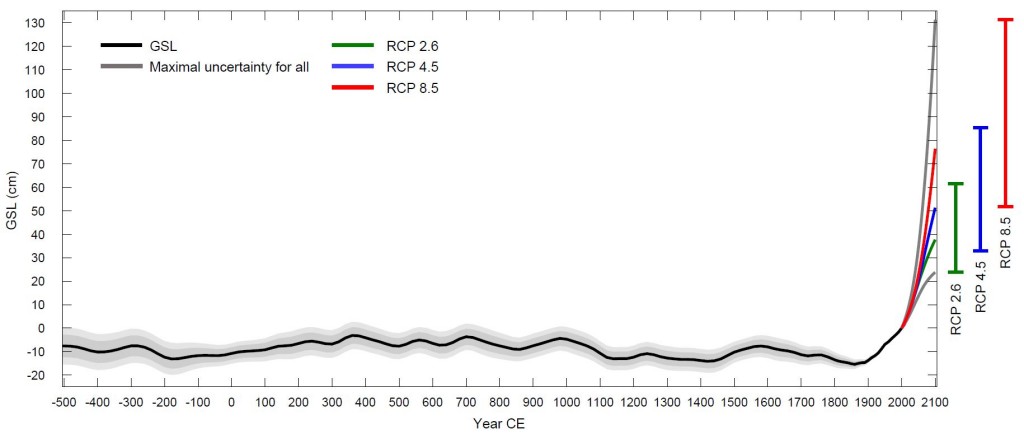

The data from the past can also be used for future projections, using a so-called semi-empirical model calibrated with the historically observed relationship between temperature and sea level. With the new data, this results in a projected increase in the 21st century of 24-131 cm, depending on our emissions and thus on the extent of global warming.

This brings us to a second study, also published this week in PNAS (Mengel et al. 2016). In this paper a new method of sea-level projections is developed. It is not based on complex models, but also on simple semi-empirical equations. But not for sea level as a whole but for the individual causes of sea-level changes: thermal expansion of sea water, melting of glaciers and mass loss of the large ice sheets. These equations are calibrated based on data from the past and then extrapolated to a warmer future. It is a kind of hybrid between the semi-empirical and the process-based approach (favored by the IPCC) to sea-level projections. The following table compares the projections of the various methods.

| Scenario | IPCC 2013 | Kopp 2016 | Mengel 2016 | Horton 2014 |

| RCP 2.6 | 28–60 | 24–61 | 28-56 | 25–70 |

| RCP 4.5 | 35–70 | 33–85 | 37-77 | n.a. |

| RCP 8.5 | 53–97 | 52–131 | 57-131 | 50–150 |

Table 1 Global sea level rise in centimeters over the 21st century according to various studies for different emission scenarios. The first scenario (RCP 2.6) assumes successful climate policies limiting global warming to about 2°C; the last (RCP 8.5), however, unabated emissions and heating by around 5°C. (The ranges indicate the 90 percent confidence intervals except for the IPCC, which only provided a 66 percent confidence interval.)

The final column shows the results of an expert survey among 90 distinguished sea-level researchers (Horton et al. 2014). The projections on the basis of very different data and models thus yield very similar results, which speaks for their robustness. With one important caveat, however: the possibility of ice sheet instability, which for many years has been hanging like a shadow over all sea-level projections. While we have a pretty good handle on melting at the surface of the ice, the physics of the sliding of ice into the ocean is not fully understood and may still bring surprises. I consider it possible that in this way the two big ice sheets may contribute more sea-level rise by 2100 than suggested by the upper end of the ranges estimated by Mengel et al. for the solid ice discharge, which is 15 cm from Greenland and 19 cm from Antarctica. (The biggest contributions to their 131 cm upper end are 52 cm from Greenland surface melt and 45 cm from thermal expansion of ocean water.)

This concern is reinforced strongly by two further new papers, also appearing in PNAS this week, by Gasson et al. and by Levy et al.. These papers look at the stability of the Antarctic Ice Sheet during the early to mid Miocene, between 23 and 14 million years ago. What is most relevant here is the advances in modelling the Antarctic ice sheet by including new mechanisms describing the fracturing of ice shelves and the breakup of large ice cliffs. The improved ice sheet model is able to capture the highly variable Antarctic ice volume during the Miocene; the bad news is that it suggests the Antarctic Ice Sheet can decay more rapidly than previously thought.

Fig. 3 The last 2500 years of sea level together with the projections of Kopp et al. for the 21st century. Future rise will dwarf natural sea-level variations of previous millennia.

Global vs. regional increase

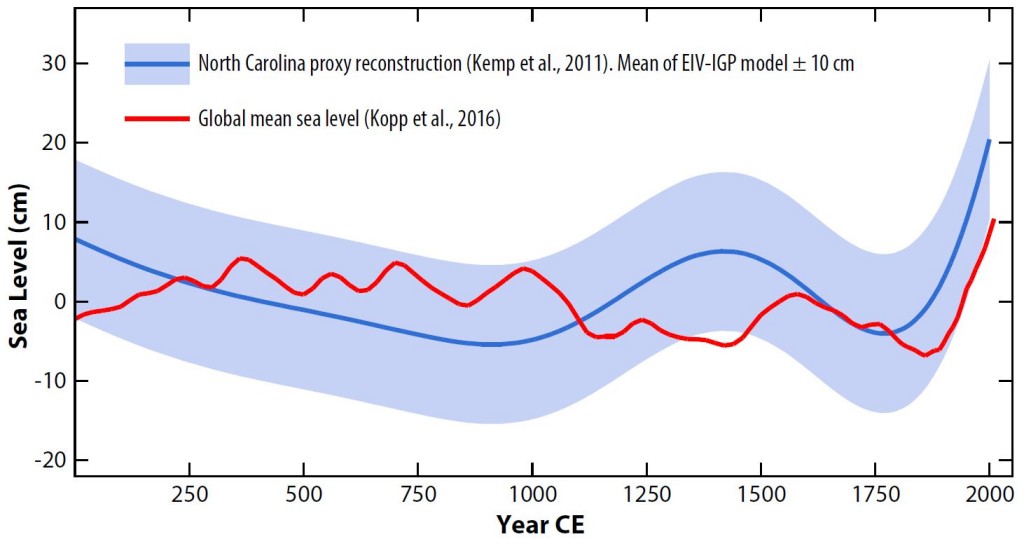

One question I was asked by a journalist was how the new results compare with our previous study (Kemp et al. 2011), which reconstructed the last two millennia of sea level in North Carolina based on cores from the Outer Banks. Sea level changes in one place can of course differ substantially from the global sea level history. In that paper we therefore estimated the expected size of these deviations on the basis of known physical processes, and came to the conclusion:

This analysis suggests that our data can be expected to track global mean sea level within about ±10 cm over the past two millennia.

The graph below shows a direct comparison of the new global and the former regional curves. (To allow a fair comparison, the uncertainty about a linear background rate discussed above was treated in the same manner in both curves, namely by removing the linear trend over the pre-industrial period AD 0-1800.)

Fig. 4 Comparison of the new global curve of Kopp et al. (2016) with the regional curve for North Carolina by Kemp et al. (2011).

As we see, our assessment wasn’t bad at all.

Ten thousand years of future sea level rise

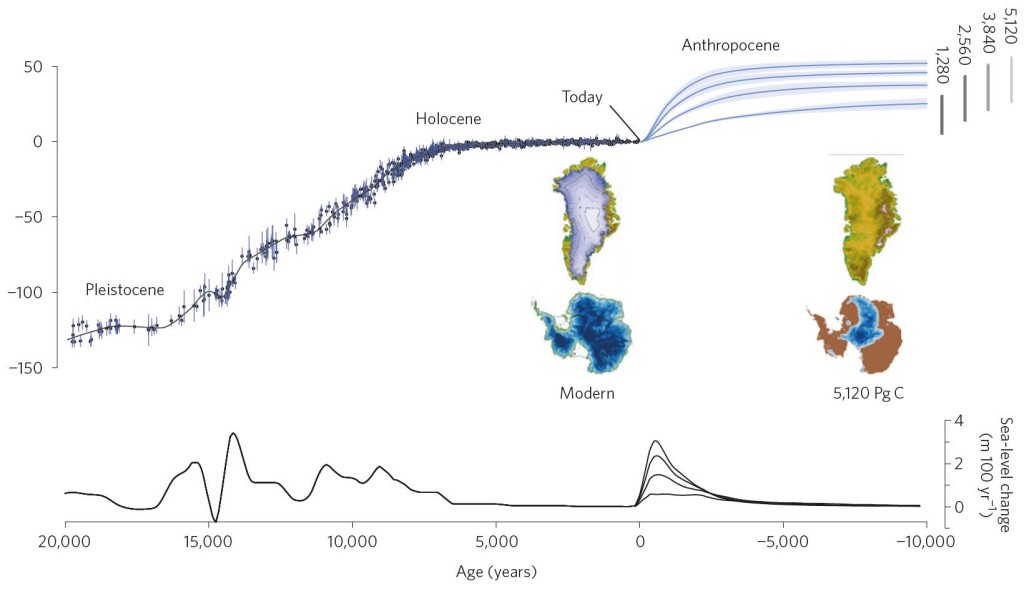

Another recent paper, by 22 renowned researchers in Nature Climate Change (Clark et al. 2016), discusses the long-term sea level rise which we will cause by our emissions of the coming decades. Largely because of the slow response of the large ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica to global warming, the sea will continue to rise for at least ten thousand years even after global warming was stopped – longer than the history of human civilization. The reason is that the lifetime of CO2 in the atmosphere is very long – even millennia after we will have stopped burning fossil fuels, the CO2 content of the atmosphere and the global temperature will continue to be higher than now, and ice will continue to melt. Even if we limit global warming to 2°C, the likely end result will be a sea-level rise of around 25 meters.

Fig. 5 From the Ice Age to the Anthropocene: the last 20,000 and the next 10,000 years of sea level, by Clark et al. 2016. The vertical scale is measured here not in cm but in meters: at the height of the last Ice Age, at the start of the curve, global sea level was about 125 meters lower than today. Due to our greenhouse gas emissions we are currently setting in motion a sea-level rise of 25 to 50 meters above present levels. The small inset maps show the ice cover on Greenland and Antarctica. The lower curves give the rate of sea-level rise in meters per century.

This expected large sea-level rise does of course not surprise us paleoclimatologists, given that in earlier warm periods of Earth’s history sea level has been many meters higher than now due to the diminished continental ice cover (see the recent review by Dutton et al. 2015 in Science).

I have often emphasized the inexorable long-term effects of sea level rise in my lectures and articles over the years. Often I was told that people don’t care about what will happen in thousands of years – they are at best interested in the lifetime of their children and grandchildren. Would you agree with that? I would hope that we do care how future generations will see the legacy that we leave them.

Links

New York Times: Seas Are Rising at Fastest Rate in Last 28 Centuries

Washington Post: Seas are now rising faster than they have in 2,800 years, scientists say

Associated Press: Seas are rising way faster than any time in past 2,800 years

Scientific American: New Data Reveal Stunning Acceleration of Sea Level Rise

Phys.org: Sea level rise in 20th century was fastest in 3,000 years, study finds

Phys.org: Sea-level rise past and future: Robust estimates for coastal planners

The Independent: Sea levels ‘could rise by more than a metre’ if global warming is not tackled, says new study

USA Today: Sea levels rising faster now than in past 3,000 years

References

- R.E. Kopp, A.C. Kemp, K. Bittermann, B.P. Horton, J.P. Donnelly, W.R. Gehrels, C.C. Hay, J.X. Mitrovica, E.D. Morrow, and S. Rahmstorf, "Temperature-driven global sea-level variability in the Common Era", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517056113

- R. Rietbroek, S. Brunnabend, J. Kusche, J. Schröter, and C. Dahle, "Revisiting the contemporary sea-level budget on global and regional scales", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, pp. 1504-1509, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1519132113

- S. Rahmstorf, "A Semi-Empirical Approach to Projecting Future Sea-Level Rise", Science, vol. 315, pp. 368-370, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1135456

- M. Mengel, A. Levermann, K. Frieler, A. Robinson, B. Marzeion, and R. Winkelmann, "Future sea level rise constrained by observations and long-term commitment", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, pp. 2597-2602, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1500515113

- B.P. Horton, S. Rahmstorf, S.E. Engelhart, and A.C. Kemp, "Expert assessment of sea-level rise by AD 2100 and AD 2300", Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 84, pp. 1-6, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.11.002

- E. Gasson, R.M. DeConto, D. Pollard, and R.H. Levy, "Dynamic Antarctic ice sheet during the early to mid-Miocene", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, pp. 3459-3464, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516130113

- R. Levy, D. Harwood, F. Florindo, F. Sangiorgi, R. Tripati, H. von Eynatten, E. Gasson, G. Kuhn, A. Tripati, R. DeConto, C. Fielding, B. Field, N. Golledge, R. McKay, T. Naish, M. Olney, D. Pollard, S. Schouten, F. Talarico, S. Warny, V. Willmott, G. Acton, K. Panter, T. Paulsen, M. Taviani, . , G. Acton, R. Askin, C. Atkins, K. Bassett, A. Beu, B. Blackstone, G. Browne, A. Ceregato, R. Cody, G. Cornamusini, S. Corrado, R. DeConto, P. Del Carlo, G. Di Vincenzo, G. Dunbar, C. Falk, B. Field, C. Fielding, F. Florindo, T. Frank, G. Giorgetti, T. Grelle, Z. Gui, D. Handwerger, M. Hannah, D.M. Harwood, D. Hauptvogel, T. Hayden, S. Henrys, S. Hoffmann, F. Iacoviello, S. Ishman, R. Jarrard, K. Johnson, L. Jovane, S. Judge, M. Kominz, M. Konfirst, L. Krissek, G. Kuhn, L. Lacy, R. Levy, P. Maffioli, D. Magens, M.C. Marcano, C. Millan, B. Mohr, P. Montone, S. Mukasa, T. Naish, F. Niessen, C. Ohneiser, M. Olney, K. Panter, S. Passchier, M. Patterson, T. Paulsen, S. Pekar, S. Pierdominici, D. Pollard, I. Raine, J. Reed, L. Reichelt, C. Riesselman, S. Rocchi, L. Sagnotti, S. Sandroni, F. Sangiorgi, D. Schmitt, M. Speece, B. Storey, E. Strada, F. Talarico, M. Taviani, E. Tuzzi, K. Verosub, H. von Eynatten, S. Warny, G. Wilson, T. Wilson, T. Wonik, and M. Zattin, "Antarctic ice sheet sensitivity to atmospheric CO 2 variations in the early to mid-Miocene", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, pp. 3453-3458, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516030113

- A.C. Kemp, B.P. Horton, J.P. Donnelly, M.E. Mann, M. Vermeer, and S. Rahmstorf, "Climate related sea-level variations over the past two millennia", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 108, pp. 11017-11022, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1015619108

- P.U. Clark, J.D. Shakun, S.A. Marcott, A.C. Mix, M. Eby, S. Kulp, A. Levermann, G.A. Milne, P.L. Pfister, B.D. Santer, D.P. Schrag, S. Solomon, T.F. Stocker, B.H. Strauss, A.J. Weaver, R. Winkelmann, D. Archer, E. Bard, A. Goldner, K. Lambeck, R.T. Pierrehumbert, and G. Plattner, "Consequences of twenty-first-century policy for multi-millennial climate and sea-level change", Nature Climate Change, vol. 6, pp. 360-369, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2923

- A. Dutton, A.E. Carlson, A.J. Long, G.A. Milne, P.U. Clark, R. DeConto, B.P. Horton, S. Rahmstorf, and M.E. Raymo, "Sea-level rise due to polar ice-sheet mass loss during past warm periods", Science, vol. 349, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa4019

Well look at that, yet another Hockey Stick. (How may does that make now?) But then, did anyone seriously expect sea level rise would show anything else?

Sea level rise has trminal crisis in its sights.

Salt water infiltration of South Florida’s fresh water supply will be a several trillion dollar hemorrhage of its real estate value. From that point on the turning point will no longer be ecological demise. It will be an economic turning point, from which the US economy will not recover.

Perhaps that +/- 50cm uncertainty should be shown on figure 1

[Response: To illustrate that effect one could show three curves: one with the best estimate trend, and two that have linear trends of + and – 0.2 mm/year added. It would probably best be done in a separate figure; showing the data uncertainty together with the trend uncertainty in one plot would be messy and hard to read. -stefan]

You ask if we should or should not care about sea-level rise in the far future. As far as I’m concerned it would be utterly selfish and immoral to ignore the problem when we know we can do something about it.

#4 “As far as I’m concerned it would be utterly selfish and immoral to ignore the problem when we know we can do something about it.”

What did you have in mind?

the dois for Levy and Gasson are

10.1073/pnas.1516030113

10.1073/pnas.1516130113

pnas is exhibiting an interesting failure mode where each article abstract leads to the pdf for the other …

Gasson is quite horrifying, may meters of sea level in far less than a millennium.

sidd

oi vey, the pdfs for the papers show the same doi ? but the abstract for each does lead to the pdf for the other, but somebody has blundered further

In line with Digby, I most certainly think we should care about what we’re leaving to those generations still alive in 2100 and way beyond. It’s unconscionable to arbitrarily limit our concern to the next 85 years. Will that also apply to those alive in 2050? If so, then they will be only considering the effects of our behaviour up to 2135 (but will they be able to do anything about it by then). That illustrates how ridiculous focusing on 2100 is. If something is dangerous (whether sea level rise of 1m or warming of 2C), it will be dangerous if it occurs in 2150 just as much as if it occurs in 2100. Moreso, if population is higher then.

You ask if we should or should not care about sea-level rise in the far future. As far as I’m concerned it would be utterly selfish and immoral to ignore the problem when we know we can do something about it.

Comment by Digby Scorgie — 22 Feb 2016 @

Don’t we already have ~60′ of SLR baked in no matter what? I guess it could get worse than that but how many people will still be around at that point? 400-500ppm of CO2 is not reversible is it?

Stefan, thanks for connecting the dots between these new papers.

Looking at fig3 in Gasson et al 2016 it seems they find about 10m of SLR in about two centuries once the ice on (West-)Antarctica starts collapsing. Let’s hope this collapse takes more than a century to really get going, but what chance would you estimate that it will get going before 2100, of even halfway this century? What is the risk of 10m of SLR between 2100-2300, or even between 2050-2250, under BAU in your expert opinion based on Gasson et al and the rest of the relevant literature that you’re alluding to? And how much could strong mitigation reduce this risk?

[Response: Good questions! I wish I knew the answers. -stefan]

I do care about the long term future a lot and am firmly convinced that many others care just as much. It would be beneficial if scientists, like in this post, put more emphasis on the long term effects of global warming in their predictions. There is much room for improvement in the IPCC reports in this domain.

Correction: Gasson et al don’t find 10m of SLR in two centuries, but in four, with about 6m in the first two, and about 4m in the next two.

Stefan, also look at fig2b in Rohling et al 2013:

http://www.nature.com/articles/srep03461/figures/2

The ice sheets could get to full response within 2-4 centuries (or it could take much longer). It may be fair to say we’re at two centuries now, since the start of industrialization. So we seem to be in risky territory.

Also see:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/02/160222155615.htm

Gasson says:

“The ice sheets will take hundreds of years to respond, so although CO2 may be at the same level as during the Miocene in the next 30 years, it doesn’t mean that they will melt in 30 years,”

No, but when will they reach their maximum melt rate? Around 2100? Around 2200? Later?

Our custodianship is of utmost importance, i couldn’t agree more.

Not questioning data but if diameter of the earth is shrinking due to whatever factors may be at work, is that a variable not considered.

#15–To repurpose one of the great quotations of antiquity:

“If.”

The graphs you present look very different from any SLR graphs I’ve ever seen, which generally reveal a steady rise in sea level going back roughly 200 years. See, for example this one: http://notrickszone.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/Caryl_Level2.gif Or this one: http://notrickszone.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/caryl_Level4.gif

Both are from this article by Ed Caryl: http://notrickszone.com/2011/02/16/a-level-look-at-sea-levels/#sthash.CuptQ9ZL.sf6EPWSz.dpbs

Also, I see no evidence from this data of anything other than a steady rise. No sudden acceleration, no “hockey stick.” Does it really matter, in any case? Won’t we have plenty of time to adapt?

From the Caryl article:

What about Bangladesh? The river silt has kept up with sea level rise so far, and will in the future, in fact, 250 years ago, much of Bangladesh was flooded all the time. . .

What about the Pacific Islands, the Maldives, etc? Coral grows much faster than 2 mm/year, and has kept up with sea level rise so far, and it will in the future. Many of those islands are only there because of coral growth.

What about our harbors? Infrastructure is continuously wearing out, being torn down, and rebuilt. The docks of 1700 are no longer there. They have been replaced, 300 mm higher.

[Response: Perhaps this is because you are looking at denialist websites? Ever even looked at a photo of Male, capital of the Maldives? Still think this is going to be saved by coral growth? (Which, as an aside, will be severely stunted by ocean acidification, if coral reefs survive at all.) The Maldives are currently building an artificial island called Hulhumale, where in 40 years 150.000 people are planned to live (more than half the current population of the Maldives). -stefan]

I find it interesting that most people do not really care about SLR beyond the 21st century and yet, when talking about nuclear energy and nuclear wastes, they expect a clear demonstration that there is no impact 100 kyr from now.

Rolan O. Clark:

Uhm, presumably “diameter of the earth is shrinking” wasn’t considered because there’s no evidence for it.

There is a growing literature in social science, law and policy on the extent to which people care about the deep future and the implications for climate mitigation. We found that people would allocate roughly $40 of $100 to buy a positive reputation after they die as opposed to a positive reputation during their lifetime (e.g., Vandenbergh & Raimi 2015, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2397818), and this is in line with other recent work on the topic (e.g., Zaval, Markowitz & Weber, 2015, and Fox, Tost, & Wade-Benzoni, 2009). We proposed a private climate legacy registry as one way to harness this concern, but there are many other options if we can get past policymakers’ almost exclusive focus on 2100.

“Often I was told that people don’t care about what will happen in thousands of years – they are at best interested in the lifetime of their children and grandchildren… I would hope that we do care how future generations will see the legacy that we leave them.”

How do we develop a sustainable civilization?

The Fractal Frontier

Sustainable Development Trilogy

http://cdn5.triplepundit.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/THE-FRACTAL-FRONTIER.pdf

Satellites provide measurement of distance from satellite to sea level. That is not quite the same as sea level itself.

The steady climb is a little too steady, in my sense of things, so my thoughts go to whether we are not seeing some orbital altitude decay, which is something that does happen. No doubt there is a calibration done from one satellite to the next. I gather this would be done based on tidal gauges.

[Response: Indeed those data are calibrated, including using GPS stations on land. And if you look at the paper by Rietbroek et al. mentioned above, you can see that the total SLR can also be understood in terms of its indididual components using independent data. -stefan]

The diameter of the Earth is not shrinking to any relevant degree.

The argument that we shouldn’t care about effects kiloyears in the offing has always struck me as morally vacuous. Are people somehow less important in the future? Do they not deserve a quality of life as good or better than our own? Worse than this is the possible legacy we leave behind, if we don’t get our act together. For not only will posterity be worse off, they will look back at our own time with disgust and a deep resentment about what could be but isn’t. A planet once full of hope consumed by ignorance and greed.

Rolan – what makes you think the diameter of earth is shrinking

“As far as I’m concerned it would be utterly selfish and immoral to ignore the problem when we know we can do something about it.”

clearly, you have not heard the story of King Canute (Cnut).

1750 to roughly 1900 looks odd. That’s when AGW is supposed to have started yet it looks like man-made influences were not yet affecting temperatures and indeed the lowest point looks like 1850. Also the error bars went away at some point even though glacial isostatic rebound is relatively new and would affect tide gauge readings prior to satellite measurement (i.e. how glacial rebound was discovered).

[Response: Postglacial rebound was discovered in the 19th Century, just check out Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-glacial_rebound#Discovery. It has been happening since the last deglaciation, and its rate changes over longer timescales than the ones we focused on here. It is close to constant over the Common Era.

Error bars don’t go away, they do shrink greatly once we have additional data from tide gauge sites and then from the global network of tide gauge sites (the Hay et al curve) available. -stefan]

Also, in Table 1 on the “Historical” line and the commment for it, I note the 5th – 95th percentile seems to take the lower limit of Mann et al, and the upper limit of Marcott et al. It seems odd that these numbers would fall out this way. The 5-95 percentile can’t just be minima/maxima of two datasets. Both provide a mean and range and they should be convolved, otherwise it appears the claim is increasing uncertainty or that the datasets are fundamentally incompatible.

[Response: You’re right, the minimum/maximum approach we took was a conservative one; had we assigned equal probability weights to either calibration, it would have narrowed the error bars.-stefan]

Figure 3 shows the sea level not to have been high during the Roman Warm Period and Medieval Warm Period. Why? Does it argue that those periods were not “warm”? Is it correct that you are forecasting the rise for the 21st century to have a higher rate than in the 20th century?

There are some who think we can do nothing to prevent sea-level rise in the far future, implying that we should sit back and do nothing.

While it is true that a certain amount of sea-level rise is inescapable, an enormous amount of sea-level rise can be avoided.

“Often I was told that people don’t care about what will happen in thousands of years – they are at best interested in the lifetime of their children and grandchildren. Would you agree with that? I would hope that we do care how future generations will see the legacy that we leave them.”

Well, based on the utter indifference most people display towards the poor, the displaced, and the enslaved RIGHT NOW (and fundamentally always have), I seriously doubt that more than a meaningless handful of humans care enough about future generations to make sacrifices now. Certainly not enough to change the trend towards an uninhabitable planet.

Happy to be wrong.

> the Roman Warm Period and Medieval Warm Period. Why?

Those were regional events, not global;

those were brief events, not longterm;

those were variability around the then norm, not increasing trends;

those were transient, not longterm geoengineering with fossil fuels

those were not sufficient to melt Greenland and the polar icecaps

those did not supply water from any source to raise sea level

But you knew that.

> if diameter of the earth is shrinking due to whatever factors

When you notice that “the world is shrinking” it’s an observer effect, not a physical change.

Your transportation, communication, network, and computer gear have been getting faster and faster for the past few decades.

It’s not the world that’s changing, it’s the way you experience it.

Please do an article on the possibility of ice sheet instability. I remember that somebody said before to not worry about it, but it is one thing I do not understand well. If an ice sheet could crumble suddenly, it would be very dangerous.

Re #17:

All the graphs on this site, and the ones you link to look roughly consistent to me. There is a slight discrepancy about what happens between 1700 and 1850. Either sea level was dropping slowly, or was roughly constant. All sources have rather large error bars in this region. Maybe the glacial isostatic adjustment in the Jevrejeva data is part of the discrepancy, I’m not sure

Either way, the change from just before 1900 to now is clear — rapidly increasing sea level, best fit by an exponentially increasing curve, unprecedented in the last 2500 years.

According to a 2014 study by Jevrejeva et al. (http://www.co2science.org/articles/V17/N20/C1.php), “the new reconstruction suggests a linear trend of 1.9 ± 0.3 mm/yr during the 20th century” and “1.8 ± 0.5 mm/yr for the period 1970-2008.” An associated graph shows a steady sea level rise beginning in the mid 19th century.

From the review in CO2 Science:

“Although some regions have recently experienced much greater rates of sea level rise, such as the Arctic (3.6 mm/yr) and Antarctic (4.1 mm/yr), with the mid-1980s even exhibiting a rate of 5.3 mm/yr (Holgate, 2007), this newest analysis of the most comprehensive data set available suggests that there has been no dramatic increase – or any increase, for that matter – in the mean rate of global sea level rise due to the historical increase in the atmosphere’s CO2 concentration.”

Can you explain why their results are so completely different from yours?

[Response: Yes. “The only outlier set which shows high early rates of SLR is the Jevrejeva et al. (2008) data – and this uses a bizarre weighting scheme, as we have discussed here at Realclimate. For example, the Northern Hemisphere ocean is weighted more strongly than the Southern Hemisphere ocean, although the latter has a much greater surface area. With such a weighting movements of water within the ocean, which cannot change global-mean sea level, erroneously look like global sea level changes.” http://www.realclimate-backup.org/index.php/archives/2013/10/sea-level-in-the-5th-ipcc-report/ and

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2013/01/sea-level-rise-where-we-stand-at-the-start-of-2013/ – gavin]

for EG:

http://www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ngeo1887.html

Diverse calving patterns linked to glacier geometry

Nature Geoscience (2013)

doi:10.1038/ngeo1887

op. cit.

For mike @26: clearly you don’t know the story of King Cnut. To demonstrate the limits of his power Cnut commanded that the tide not come in, not that his subjects stop burning fossil carbon and thereby avoid melting the polar ice caps. Notice the difference?

UNLESS we start projects to sequester CO²; there are pilot projects and initiatives, some of which have net energy output, and others which do not seem undoable (leveraging natural olivine weathering processes), at least not if the future of the planet is at stake. These would mitigate the long term effects of the warming pulse to which we will subject the climate.

Lennart @ # 13

You said “No, but when will they reach their maximum melt rate? Around 2100? Around 2200? Later?

Why do you focus on 2100 or 2200? It is incremental sea level rise that should be your focus.

Each increment of rise will impact some coastal area somewhere on the globe.

How about enough sea level rise to infiltrate Florida’s fresh water resources? Is that a concern? When? 2030- 2040 or when?

That will be the focus of a collapse of the real estate market in Florida and the onset of financial collapse of US economy and civil chaos as people abandon South Florida. Is that a better way to focus your attention?

So, yeah (did I already say this?) — I would agree with EG that it would be appropriate to see a writeup about the worst-case-so-far notion of “catastrophic disintegration” mentioned a few years ago, noted at

https://www.realclimate.org/?comments_popup=15633#comment-404270

I’m old enough to remember when the great ice caps were stable for a thousand years to come — that was back when the continents hadn’t started drifting either, of course. You youngsters have no idea how recently that all happened.

I took college geology the summer Apollo 11 landed on the Moon.

That was the last year the standard course taught the old geology — the year _before_ continental drift finally, formally, officially replaced the old idea that longterm erosion, creating synclines and antisynclines, explained those odd folds and rifts in the continents.

I can’t recall exactly when the great ice caps started to show weakness.

I know I tracked papers for a while over at Stoat, in the “Why do Science in Antarctica” thread. Turned out one reason was that, surprising at the time, Antarctica was changing fast. I recall how in one paper, one day, drumlins changed from longterm slow erosional features to rapidly formed shapes in meltwater flows below the ice caps — I remember that paper well. Surprise!

Rates of change alter in scientific understanding, as well as in ecology.

Xref, when the changes were appearing:

Why do Science in Antarctica? – Stoat – ScienceBlogs

http://scienceblogs.com/stoat/2007/02/05/why-do-science-in-antarctica/

Feb 5, 2007 – “Rapid Sediment Erosion and Drumlin Formation Observed Beneath a Fast-Flowing Antarctic Ice Stream” – American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2005

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2005AGUFM.C13A..04S

“… Our results are the first observations from a modern glacial analogue of processes that have so far only been modelled theoretically or interpreted from former glaciated regions. They allow us to discriminate between a number of different theories of subglacial erosion and bedform generation as well as quantifying the rates of a number of subglacial processes.”

The tires on my car are balding. I wonder how many miles before they fail? One person tells me they are good for 10,000 miles. Another tells me I should replace them now. What if one picks up a nail or blows while driving on the highwayy. The windshield is cracke, the frame rusted, brakes a rubbing metal and let’s not mention the sludge in the oil pan. The vehicle is beyond repair.

If we do not change our human ways, nothing matters.

#29 MatthewRMarler:

First, the rate of global sea-level change in the 20th century (1.4 ± 0.2 mm/yr) was, with 95% probability, faster than during any century since at least 800 BCE. (And the 800 BCE date is not because the rate of global sea-level rise was probably faster before then, but simply that the reconstruction quality isn’t good enough before then to have the same level of confidence.)

Second, the 20th century wasn’t the only time period when temperature and global sea level changed together. Global sea level underwent a statistically robust fall of 8 ± 8 cm (95% probability interval) over 1000-1400 CE, coincident with a decline in global temperature of ~0.2°C. Notably, both the decline in sea level and the decline in temperature occurred during the so-called European “Medieval Warm Period,” providing additional evidence that the “Medieval Warm Period” and “Little Ice Age” were not globally synchronous phenomena.

–Bob Kopp, Rutgers Dept. of Earth & Planetary Sciences and Rutgers Energy Institute.

http://www.bobkopp.net/160222-pnas-commonera/

“The 20th-century rise was extraordinary in the context of the last three millennia – and the rise over the last two decades has been even faster…”

“The statistical challenge is to pull out the global signal.”

http://news.rutgers.edu/news/sea-level-rise-20th-century-was-fastest-3000-years-rutgers-led-study-finds/20160217#.Vs8OCimoKo_

Hansen on rate of SLR

John #40,

You’re right of course that more and more effects of SLR will be felt already before 2100 or 2200. Some people think however those earlier effects may be manageable on a global scale, although maybe not on a local scale, like you mention for Miami. That’s why I’m also interested in the long term SLR and maximum potential rate of SLR: those determine the ultimate (un)manageability of SLR, and those risks seem to be most neglected or under-estimated. But again, I think you’re right that earlier effects of SLR may already be challenging enough.

> Victor … the review in CO2 Science

> … Can you explain why their results are

> so completely different from yours?

Because they lie, Victor. They’re notorious.

CO2 Science twists the most recent science, ever so subtly

-0- blogs.nature.com/climatefeedback

This video of a lecture by Richard Alley where he points out that:

1) We don’t know when Thwaites will cross its tipping point

2) When it does, it is likely to totally collapse in a matter of decades, raising sea levels in the Northern hemisphere by f o u r m e t e r s.

He doesn’t think it highly likely that this will happen this century, but that it can’t be ruled out (fat tail, and all that).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yCunWFmvUfo

“Often I was told that people don’t care about what will happen in thousands of years”

Wise words. The United States has existed as a nation little over 200 years. Let’s go back just one thousand years, to 1016 and from there look forward 1000 years. How many predictions projections or wild guesses will have come true or even been imagined?

http://www.lascelleshistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Time-Line.jpg

North America will still have humans inhabiting, most likely, 200 years from now but whether the United States will still resemble its creation, probably not, there’s not much left of it already.

You worry about legacy. How much history do you possess written only one thousand years ago? How much of today’s history will be available to anyone one thousand years from now? Much modern writing is ephemeral. One big EMP and billions of photographs and written records will simply vanish.

So, yes, I worry a lot more about the next 50 years.

@ 37 Hank Roberts says: (24 Feb 2016 at 10:55 AM)

Thank you very much, Mr. Roberts, for the “complimentary access” to the paper by Bassis and Jacobs. Their research, coupled with what Hansen says in the greenman interview linked by #45 Killan (25 Feb 2016 at 11:13 AM, thank you, too) should heighten the concerns and accelerate further investigation into potential ice-shelf/glacier collapse possibilities. I was a bit dismayed that Hansen didn’t mention that rising sea-level will also increase shear stresses (referenced by Bassis & Jacobs) on ice-shelves/tongues as well as increase seabed pressures leading to deeper (inland) incursion of [warm-ish?] sea-water under “grounded” ice.