In a comment in Nature titled Ditch the 2 °C warming goal, political scientist David Victor and retired astrophysicist Charles Kennel advocate just that. But their arguments don’t hold water.

It is clear that the opinion article by Victor & Kennel is meant to be provocative. But even when making allowances for that, the arguments which they present are ill-informed and simply not supported by the facts. The case for limiting global warming to at most 2°C above preindustrial temperatures remains very strong.

Let’s start with an argument that they apparently consider especially important, given that they devote a whole section and a graph to it. They claim:

The scientific basis for the 2 °C goal is tenuous. The planet’s average temperature has barely risen in the past 16 years.

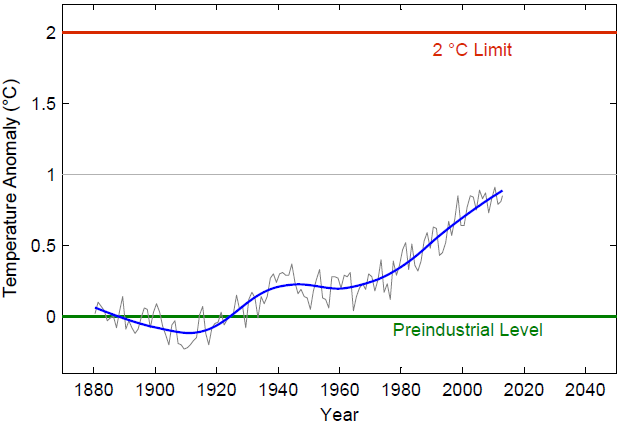

They fail to explain why short-term global temperature variability would have any bearing on the 2 °C limit – and indeed this is not logical. The short-term variations in global temperature, despite causing large variations in short-term rates of warming, are very small – their standard deviation is less than 0.1 °C for the annual values and much less for decadal averages (see graph – this can just as well be seen in the graph of Victor & Kennel). If this means that due to internal variability we’re not sure whether we’ve reached 2 °C warming or just 1.9 °C or 2.1 °C – so what? This is a very minor uncertainty. (And as our readers know well, picking 1998 as start year in this argument is rather disingenuous – it is the one year that sticks out most above the long-term trend of all years since 1880, due to the strongest El Niño event ever recorded.)

The logic of 2 °C

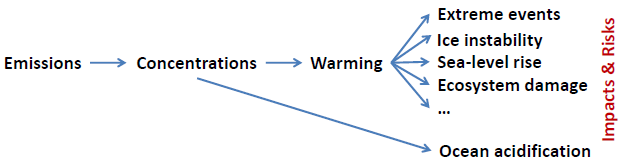

Climate policy needs a “long-term global goal” (as the Cancun Agreements call it) against which the efforts can be measured to evaluate their adequacy. This goal must be consistent with the concept of “preventing dangerous climate change” but must be quantitative. Obviously it must relate to the dangers of climate change and thus result from a risk assessment. There are many risks of climate change (see schematic below), but to be practical, there cannot be many “long-term global goals” – one needs to agree on a single indicator that covers the multitude of risks. Global temperature is the obvious choice because it is a single metric that is (a) closely linked to radiative forcing (i.e. the main anthropogenic interference in the climate system) and (b) most impacts and risks depend on it. In practical terms this also applies to impacts that depend on local temperature (e.g. Greenland melt), because local temperatures to a good approximation scale with global temperature (that applies in the longer term, e.g. for 30-year averages, but of course not for short-term internal variability). One notable exception is ocean acidification, which is not a climate impact but a direct impact of rising CO2 levels in the atmosphere – it is to my knowledge currently not covered by the UNFCCC.

From emissions to impacts.

Once an overall long-term goal has been defined, it is a matter of science to determine what emissions trajectories are compatible with this, and these can and will be adjusted as time goes by and knowledge increases.

Why not use limiting greenhouse gas concentrations to a certain level, e.g. 450 ppm CO2-equivalent, as long-term global goal? This option has its advocates and has been much discussed, but it is one step further removed from the actual impacts and risks we want to avoid along the causal chain shown above, so an extra layer of uncertainty is added. This uncertainty is that in climate sensitivity, and the overall range is a factor of three (1.5-4.5 °C) according to IPCC. This would mean that as scientific understanding of climate sensitivity evolves in coming decades, one might have to re-open negotiations about the “long-term global goal”. With the 2 °C limit that is not the case – the strategic goal would remain the same, only the specific emissions trajectories would need to be adjusted in order to stick to this goal. That is an important advantage.

2 °C is feasible

Victor & Kennel claim that the 2 °C limit is “effectively unachievable”. In support they only offer a self-citation to a David Victor article, but in fact they disagree with the vast majority of scientific literature on this point. The IPCC has only this year summarized this literature, finding that the best estimate of the annual cost of limiting warming to 2 °C is 0.06 % of global GDP (1). This implies just a minor delay in economic growth. If you normally would have a consumption growth of 2% per year (say), the cost of the transformation would reduce this to 1.94% per year. This can hardly be called prohibitively expensive. When Victor & Kennel claim holding the 2 °C line is unachievable, they are merely expressing a personal, pessimistic political opinion. This political pessimism may well be justified, but it should be expressed as such and not be confused with a geophysical, technological or economic infeasibility of limiting warming to below 2 °C.

Because Victor & Kennel complain about policy makers “chasing an unattainable goal”, they apparently assume that their alternative proposal of focusing on specific climate impacts would lead to a weaker, more easily attainable limit on global warming. But they provide no evidence for this, and most likely the opposite is true. One needs to keep in mind that 2 °C was already devised based on the risks of certain impacts, as epitomized in the famous “reasons of concern” and “burning embers” (see the IPCC WG2 SPM page 13) diagrams of the last IPCC reports, which lay out major risks as a function of global temperature. Several major risks are considered “high” already for 2 °C warming, and if anything the many of these assessed risks have increased from the 3rd to the 4th to the 5th IPCC reports, i.e. may arise already at lower temperature values than previously thought.

One of the rationales behind 2 °C was the AR4 assessment that above 1.9 °C global warming we start running the risk of triggering the irreversible loss of the Greenland Ice Sheet, eventually leading to a global sea-level rise of 7 meters. In the AR5, this risk is reassessed to start already at 1 °C global warming. And sea-level projections of the AR5 are much higher than those of the AR4.

Even since the AR5, new science is pointing to higher risks. We have since learned that parts of Western Antarctica probably have already crossed the threshold of a marine ice sheet instability (it is well worth reading the commentaries by Antarctica experts Eric Rignot or Anders Levermann on this development). And that significant amounts of potentially unstable ice exist even in East Antarctica, held back only by small “ice plugs”. Regarding extreme events, we have learnt that record-breaking monthly heat waves have already increased five-fold above the number in a stationary climate. (These are heat waves like in Europe in 2003, causing ~ 70.000 fatalities.)

And we should not forget that after 2 °C warming we will be well outside the range of temperature variation of the entire Holocene; the planet will be hotter than anything experienced during human civilisation.

If anything, there are good arguments to revise the 2 °C limit downward. Such a possible revision is actually foreseen in the Cancun Agreements, because the small island nations and least developed countries have long pushed for 1.5 °C, for good reasons.

Uncritically adopted?

Victor & Kennel claim the 2 °C guardrail was “uncritically adopted”. They appear to be unaware of the fact that it took almost twenty years of intense discussions, both in the scientific and the policy communities, until this limit was agreed upon. As soon as the world’s nations agreed at the 1992 Rio summit to “prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”, the debate started on how to specify the danger level and operationalize this goal. A “tolerable temperature window” up to 2 °C above preindustrial was first proposed as a practical solution in 1995 in a report by the German government’s Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU). It subsequently became the climate policy guidance of first the German government and then the European Union. It was formally adopted by the EU in 2005.

Also in 2005, a major scientific conference hosted by the UK government took place in Exeter (covered at RealClimate) to discuss and describe scientifically what “avoiding dangerous climate change” means. The results were published in a 400-page book by Cambridge University Press. Not least there are the IPCC reports as mentioned above, and the Copenhagen Climate Science Congress in March 2009 (synthesis report available in 8 languages), where the 2 °C limit was an important issue discussed also in the final plenary with then Danish Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen (‘Don’t give us too many moving targets – it is already complex’).

After further debate, 2 °C was finally adopted at the UNFCCC climate summit in Cancun in December 2010. Nota bene as an upper limit. The official text (Decision 1/CP.16 Para I(4)) pledges

to hold the increase in global average temperature below 2 °C above pre- industrial levels.

So talking about a 2 °C “goal” or “target” is misleading – nobody in their right mind would aim to warm the climate by 2 °C. The goal is to avoid just that, namely keeping warming below 2 °C. As an upper limit it was also originally proposed by the WBGU.

What are the alternatives?

Victor & Kennel propose to track a bunch of “vital signs” rather than global-mean surface temperature. They write:

What is ultimately needed is a volatility index that measures the evolving risk from extreme events.

As anyone who has ever thought about extreme events – which by definition are rare – knows, the uncertainties relating to extreme events and their link to anthropogenic forcing are many times larger than those relating to global temperature. It is rather illogical to complain about ~0.1 °C variability in global temperature, but then propose a much more volatile index instead.

Or take this proposal:

Because energy stored in the deep oceans will be released over decades or centuries, ocean heat content is a good proxy for the long-term risk to future generations and planetary-scale ecology.

It seems that the authors are not getting the physics of the climate system here. The deep oceans will almost certainly not release any heat for at least a thousand years to come; instead they will continue to absorb heat while slowly catching up with the much greater surface warming. It is also unclear what the amount of heat stored in the deep ocean has to do with risks and impacts at our planet’s surface – if deep ocean heat uptake increases (e.g. due to a reduction in deep water renewal rates, as predicted by IPCC), how would this affect people and ecosystems on land?

Vital Signs

The idea to monitor other vital signs of our home planet and to keep them within acceptable bounds is of course neither bad nor new. In fact, in addition to the 2 °C warming limit the WBGU has also proposed to limit ocean acidification to at most 0.2 (in terms of reduction of the mean pH of the global surface ocean) and to limit global sea-level rise to at most 1 meter. And there is a high-profile scientific debate about further planetary boundaries which Victor & Kennel don’t bother mentioning, although the 2009 Nature paper A safe operating space for humanity by Rockström et al. already has clocked up 932 citations in Web of Science. The key difference to Victor & Kennel, apart from the better scientific foundation of these earlier proposals, is that these bounds are intended as additional and complementary to the 2 °C limit and not to replace it.

If one wanted to sabotage the chances for a meaningful agreement in Paris next year, towards which the negotiations have been ongoing for several years, there’d hardly be a better way than restarting a debate about the finally-agreed foundation once again, namely the global long-term goal of limiting warming to at most 2 °C. This would be a sure recipe to delay the process by years. That is time which we do not have if we want to prevent dangerous climate change.

Footnote

(1) According to IPCC, mitigation consistent with the 2°C limit involves annualized reduction of consumption growth by 0.04 to 0.14 (median: 0.06) percentage points over the century relative to annualized consumption growth in the baseline that is between 1.6% and 3% per year. Estimates do not include the benefits of reduced climate change as well as co-benefits and adverse side-effects of mitigation. Estimates at the high end of these cost ranges are from models that are relatively inflexible to achieve the deep emissions reductions required in the long run to meet these goals and/or include assumptions about market imperfections that would raise costs.

Links

The Guardian: Could the 2°C climate target be completely wrong?

We have covered just the main points – a more detailed analysis [pdf] of the further questionable claims by Victor and Kennel has been prepared by the scientists from Climate Analytics.

Climate Progress: 2°C Or Not 2°C: Why We Must Not Ditch Scientific Reality In Climate Policy

Carbon Brief: Scientists weigh in on two degrees target for curbing global warming. Lots of leading climate scientists comment on Victor & Kennel (none agree with them).

Jonathan Koomey: The Case for the 2 C Warming Limit

Robert Watson and Marlene Moses: Is it time to abandon 2 degrees?

Update 6 October: David Victor has posted a lengthy response at Dot Earth. I was most surprised by the fact that he says that I use “the same tactics that are often decried of the far right—of slamming people personally with codewords like “political scientist” and “retired astrophysicist” to dismiss us as irrelevant”. I did not know either author, so I looked up Thomson Reuters Web of Science (as I routinely do) to see what their field of scientific work is. I have no idea why calling someone a political scientist or astrophysicist are “codewords” (for what?) or could be taken as “ad hominem slam” (I’m proud to have started my career in astrophysics), or why a political scientist should not be exactly the kind of person qualified to comment on the climate policy negotiation process. I thought that this is just the kind of thing political scientists analyse. In any case I want to make very clear that characterising these scientists by naming their fields of scientific work was not intended to call into question their expertise, nor did my final paragraph intend to imply they are trying to sabotage an agreement in Paris – I just fear that this would be the (surely unintended) effect if their proposal were to be adopted.

It seems that the authors are not getting the physics of the climate system here. The deep oceans will almost certainly not release any heat for at least a thousand years to come; –

Can you explain this a little more in detail? How much of the excess heat trapped by higher Co2 levels in the atmosphere is the ocean absorbing? There must be some heat re-emitted or at least the absorption rate is declining over a small time frame. If I were to take your statement out of context I might conclude that we can rely on the oceans to cool the planet for the next thousand years and have nothing to worry about with regard to C02 at least in the next 125 years, roughly seven generations.

[Response: Because of the large heat capacity of the oceans, it takes a lot of energy to warm them up.If you think about a new warmer equilibrium state after CO2 has increased and stabilised, this will be associated with warmer sea surface temperatures and because of the ocean circulation, it will have to be associated with warmer oceans at depth. Thus the ocean heat content has to rise before the equilibrium can be reached. That energy has to have come from the planetary imbalance set up by the forcings in the first place. So, increases in OHC are indicative of a continuing imbalance, and ocean surface temperatures will need to increase before we get to equilibrium, but the heat that is going in to the ocean right now is not going to leave. – gavin]

This piece starts with the line: “In a comment in Nature titled Ditch the 2 °C warming goal, political scientist David Victor and retired astrophysicist Charles Kennel advocate just that.”

Let me point out WHO David Victor and Charles Kennel really are:

David Victor is one of the two Coordinating Lead Authors for Chapter 1, a Lead Author of the Summary for Policymakers, and a Lead Author of the Technical Summary of the latest IPCC report. He is also the author of “Global Gridlock” a book about Climate Policy.

Charles Kennel has been an Associate Administrator of NASA, Director of NASA’s Mission to Planet Earth, Chair of the NASA Advisory Council (NAC) Science Committee, a Director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Chair of the National Academy of Science’s Space Studies Board.

Not quite “just” a political scientist and a retired astrophysicist as implied by Dr. Rahmstorf.

I thought both articles deeply flawed; the Real Climate response is confused and just plain incorrect on many counts. The Nature article was waving a white flag at the business as usual agenda.

I have been shocked by the absence, from the article and the subsequent online debate, of any mention of the public as having a role in deliberations on acceptable climate risk. If we are facing our biggest ever crisis, if we are democratic societies and if, as the IPCC and UNFCCC continuously repeat, deciding how much is too much is a value and ethical choice, then where are the people in this process?

I frequent RC, but do not live here. What the site has meant for me, across several years, is a source of rock-solid, unassailable, facts and descriptions of scientific relationships. As in, I cannot recall having picked up something on a RC keypost, taken it to the bank, and later found that me money went missing.

I did not recognize the reputations of the two authors, so I did not develop heart burn with the early exposition. When I hit “cost” of constraining CO2 is but half more than the current volumetric ratio, or a 0.6 per mil hit to global growth–that is an assertion so wildly outside of my notions of the RC realm, as to risk reputation. As if, for the first time, I had encountered an RC-sanctioned author describing the relationship between recent rainfall in Uganda and the influence of Neptune’s moons.

A frequent contributor to the old, before the bust, Oil Drum site went by “Gail the Actuary.” She argues, that declining thermodynamic returns in petroleum recovery (geology) expose the existing global pension architecture to eventual failure, much less the contemplation of politically imposed C constraints.

1. “WATER WARS” article in

Foreign Policy maga zine in DC -2014.9.18.

Shane Harris wrote: “Public anxiety — and fascination — has given rise to a new genre of films, “cli-fi,” with apocalyptic climate-change scenarios at the heart of their …”

2. Major wire service just told me today THEY WILL DO A MAJOR CLI FI news story on the worldwide global wire middle of November in connection with INTERSTELLAR release of movie

3. Peter Sinclair cartoonist activist headline on his post of Interstellar Trailer part 2 says “INTERSTELLAR may be cli fi classic”

4. Taipie Times newspapers runs my oped on the CLI FI MOVIE AWARDS here today

http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2014/10/05/2003601306

Jim (#41),

I think Hansen is correct in Storms when he says that we will never have another ice age.

There is a saying in real estate that they are not making any more land. That is something that climate control could change and would likely out weight Victor’s odd economic objections to technology that could do that. Just the chance to build a new row of hotels at Waikiki would pay for a great deal of sequestration.

“The case for limiting global warming to at most 2°C above preindustrial temperatures remains very strong.”

Sure it is. If you ignore all the evidence, the lag times, the disappearing ice, the albedo effect, the deep oceans, methane contributions, the suspended aerosols (which MUST continue) and the whole of industrialized civilization that continues to insist “let’s do more”.

This is why I do not read this site anymore. Ever since Gavin left, this site has gone to the dogs.

(And as our readers know well, picking 1998 as start year in this argument is rather disingenuous – it is the one year that sticks out most above the long-term trend of all years since 1880, due to the strongest El Niño event ever recorded.)

How about 1880 being a disingenuous start? It is not only “the start” of the Industrial Age but also the end of the Little Ice Age.

[Response: For a look further back in time, try the article about the Holocene that I linked to above. https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2013/09/paleoclimate-the-end-of-the-holocene/langswitch_lang/en/ -Stefan]

There is a different approach to this. It’s not 2C, it’s not another climatic metric. I say, ditch the whole climate discussion in politics as it is now. But read on, I’ll get back to the climate.

The current path is clearly not working convincingly well. What the world is craving for is abundant, cheap energy. Almost free, and available for everyone, rich and poor. Obviously, fossil fuels cannot provide that, not even if we believe it’s altogether harmless. So scientists and politicians need to get together and discuss how science must move towards the promise of abundant energy, and the climate goals will simply be biproducts, as well as the abolishment of poverty, rapid technological advancements, etc. But currently the climate discussion seems to stall discussions on what I believe is the core problem to solve.

Technology advances in steps, and this will take time, and it also involves acknowledging fossil fuels as a necessary step on the technological ladder. But in 2014 we should have been mostly over to the next step. Whose name is taboo on RC. We can try to skip that step and move directly to the next, whatever that is. In the meantime, however, we’re likely going to keep on burning fossil fuel as we’re used to. Ending the current discussions and start talking about the next technological levels will not in any way be a concession of any view in the debate, apart from that it is a better approach strategically.

My 2c(ents).

56 Chris D said, “Just the chance to build a new row of hotels at Waikiki would pay for a great deal of sequestration. ”

We have a lot of assets at the shoreline that will be degraded or even useless if sea levels fall. The cold climate regime needed to produce your goal would devastate farming and ecosystems. And there’s only one coastline. Drop the water and build a new row of hotels and you end up with two rows of hotels. You can get the same end result just by building a row inland.

Jim (#60),

Location, location, location! You’ve completely forgotten the new Saharan breadbasket. Start buying acreage now to get in on the ground floor! It seems quite clear that the economic objections to mitigation evaporate if we consider the benefits of super-mitigation.

Steinar,

Of course we could lie to ourselves and pretend that there is a way to have endless cheap energy without downsides. I’m not sure exactly how that would help us in the long term, though.

Tony (#62),

Care to explain what contradiction you see between “endless” and “long term”?

While there are many reasons to be skeptical that a 2 C limit is safe, the more numerous and urgent those reasons, the more dramatically less safe a 2.5 C or 3 C or 4 C limit would be. An international binding agreement on a 2 C limit does not preclude further agreement to cut the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to below 350 ppm, for example, just as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade does not prevent OPEC from ceasing its collusion in restraint of trade.

I do think the 2 C limit is frequently used to anticipate going right up to it, however, contrary to Stefan’s thinking. For example, the fossil fuels divestment movement identifies future stranded assets based on the cumulative carbon budget that the 2 C limit implies. Richard Millar makes such calculations in the most recent RC post. https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2014/10/climate-response-estimates-from-lewis-curry/

Very likely, the 2 C limit must be superseded. But for that very reason, it can’t be ditched.

SA (#50),

That was only OT for a few months. There are a number of efforts looking particularly at China and India which are finding they have been on the wrong energy track and that refocusing on renewables will have great economic benefit.

In the face of possible adverse impacts of catastrophic climate change, virtually all ethical approaches suggest that something should be done to reduce the associated risks.

Policymakers, scientists, and social scientists have debated a wide array of responses to the realities and prospects of anthropogenic climate change. The focus of this review is on the 2 degrees C temperature target, described as the maximum allowable warming to avoid dangerous anthropogenic interference in the climate.

What will 2 degrees C do to agriculture? How bad will the dust bowl be? The Rain Move is the important thing because empty grocery stores signal the end of civilization and the beginning of the global famine.

Can anybody peg 2 degrees C to a point on the agricultural output curve?

What will be happening to our food supply at 2 degrees C of warming? Can GCMs predict desertification and whatever you call the opposite of desertification yet? At what warming will the average American realize that something has happened? What do you call the opposite of desertification?

I would frame the argument in terms of food. Six Degrees by Mark Lynas says that there is a major food impact at 1 degree C of warming. I read somewhere that GW has already cost American farmers billions of dollars. But food prices here have not been impacted much. Will most people be able to associate food prices with GW? I think not, even if we tell them.

Is the 2 degree limit is the short term sensitivity? And the long term sensitivity is twice the short term sensitivity. So a 2 degree limit is really a 4 degree limit.

51 Response

” because of the ocean circulation, it will have to be associated with warmer oceans at depth. Thus the ocean heat content has to rise before the equilibrium can be reached”

Gavin, every decade or so the audience should be reminded that this controversy began a generation ago with the observation that the thermal mass of the first ten meters of ocean depth is roughly equivalent to the thermal mass of the atmosphere.

As the vertical mixing time of the deep hydrosphere is on the order of five to seven centuries, the time scale for achieving that new thermal equilibrium puts the 100 Years War to shame — it will take roughly 30 generations , so framing enthusiasts of all stripes had better start planting sequoia seeds now.

Well, this is a revolting development: results suggest that disgusting pictures evoke very different emotional processing in conservatives and liberals

I wonder if that includes climate pictures.