A new study by Screen and Simmonds demonstrates the statistical connection between high-amplitude planetary waves in the atmosphere and extreme weather events on the ground.

Guest post by Dim Coumou

There has been an ongoing debate, both in and outside the scientific community, whether rapid climate change in the Arctic might affect circulation patterns in the mid-latitudes, and thereby possibly the frequency or intensity of extreme weather events. The Arctic has been warming much faster than the rest of the globe (about twice the rate), associated with a rapid decline in sea-ice extent. If parts of the world warm faster than others then of course gradients in the horizontal temperature distribution will change – in this case the equator-to-pole gradient – which then could affect large scale wind patterns.

Several dynamical mechanisms for this have been proposed recently. Francis and Vavrus (GRL 2012) argued that a reduction of the north-south temperature gradient would cause weaker zonal winds (winds blowing west to east) and therefore a slower eastward propagation of Rossby waves. A change in Rossby wave propagation has not yet been detected (Barnes 2013) but this does not mean that it will not change in the future. Slowly-traveling waves (or quasi-stationary waves) would lead to more persistent and therefore more extreme weather. Petoukhov et al (2013) actually showed that several recent high-impact extremes, both heat waves and flooding events, were associated with high-amplitude quasi-stationary waves.

Intuitively it makes sense that slowly-propagating Rossby waves lead to more surface extremes. These waves form in the mid-latitudes at the boundary of cold air to the north and warm air to the south. Thus, with persistent strongly meandering isotherms, some regions will experience cold and others hot conditions. Moreover, slow wave propagation would prolong certain weather conditions and therefore lead to extremes on timescales of weeks: One day with temperatures over 30oC in say Western Europe is not really unusual, but 10 or 20 days in a row will be.

But although it intuitively makes sense, the link between high-amplitude Rossby waves and surface extremes was so far not properly documented in a statistical way. It is this piece of the puzzle which is addressed in the new paper by Screen and Simmonds recently published in Nature Climate Change (“Amplified mid-latitude planetary waves favour particular regional weather extremes”).

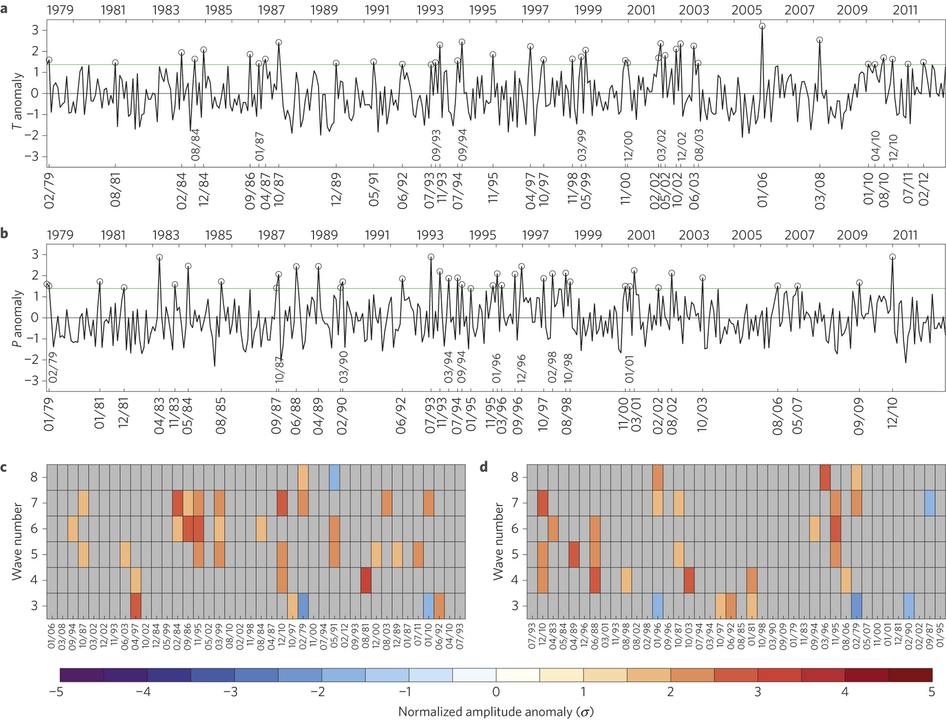

In a first step they extract the 40 most extreme months in the mid-latitudes for both temperature and precipitation in the 1979-2012 period, using all calendar months. They do this by averaging absolute values of temperature and precipitation anomalies, which is appropriate since planetary waves are likely to induce both negative and positive anomalies simultaneously in different regions. This way they determine the 40 most extreme months and also 40 moderate months, i.e., those months with the smallest absolute anomalies. By using monthly-averaged data, fast-traveling waves are filtered out and thus only the quasi-stationary component remains, i.e. the persistent weather conditions. Next they show that roughly half of the extreme months were associated with statistically significantly amplified waves. Vice versa, the moderate months were associated with reduced wave activity. So this nicely confirms statistically what one would expect.

Figure: a,b, Normalized monthly time series of mid-latitude–(35°–60° N) mean land-based absolute temperature anomalies (a) and absolute precipitation anomalies (b), 1979–2012. The 40 months with the largest values are identified by circles and labelled on the lower x axis, and the green line shows the threshold value for extremes. c,d, Normalized wave amplitude anomalies, for wave numbers 3–8, during 40 months of mid-latitude–mean temperature extremes (c) and precipitation extremes (d). The months are labelled on the abscissa in order of decreasing extremity from left to right. Grey shading masks anomalies that are not statistically significant at the 90% confidence level; specifically, anomalies with magnitude smaller than 1.64σ, the critical value of a Gaussian (normal) distribution for a two-tailed probability p = 0.1. Red shading indicates wave numbers that are significantly amplified compared to average and blue shading indicates wave numbers that are significantly attenuated compared to average. [Source: Screen and Simmonds, Nature climate Change]

The most insightful part of the study is the regional analysis, whereby the same method is applied to 7 regions in the Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes. It turns out that especially those regions at the western boundary of the continents (i.e., western North America and Europe) show the most significant association between surface extremes and planetary wave activity. Here, moderate temperatures tend to be particularly associated with reduced wave amplitudes, and extremes with increased wave amplitudes. Further eastwards this link becomes less significant, and in eastern Asia it even inverts: Here moderate temperatures are associated with amplified waves and extremes with reduced wave amplitudes. An explanation for this result is not discussed by the authors. Possibly, it could be explained by the fact that low wave amplitudes imply predominantly westerly flow. Such westerlies will bring moderate oceanic conditions to the western boundary regions, but will bring air from the continental interior towards East Asia.

Finally, the authors redo their analysis once more but now for each tail of the distribution individually. Thus, instead of using absolute anomalies, they treat cold, hot, dry and wet extremes separately. This way, they find that amplified quasi-stationary waves “increase probabilities of heat waves in western North America and central Asia, cold outbreaks in eastern North America, droughts in central North America, Europe and central Asia and wet spells in western Asia.” These results hint at a preferred position (i.e., “phase”) of quasi-stationary waves.

With their study, the authors highlight the importance of quasi-stationary waves in causing extreme surface weather. This is an important step forward, but of course many questions remain. Has planetary wave activity changed in recent decades or is it likely to do so under projected future warming? And, if it is changing, is the rapid Arctic warming indeed responsible?

References

- J.A. Francis, and S.J. Vavrus, "Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in mid‐latitudes", Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 39, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051000

- E.A. Barnes, "Revisiting the evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in midlatitudes", Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 40, pp. 4734-4739, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/grl.50880

- V. Petoukhov, S. Rahmstorf, S. Petri, and H.J. Schellnhuber, "Quasiresonant amplification of planetary waves and recent Northern Hemisphere weather extremes", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, pp. 5336-5341, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222000110

- J.A. Screen, and I. Simmonds, "Amplified mid-latitude planetary waves favour particular regional weather extremes", Nature Climate Change, vol. 4, pp. 704-709, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/NCLIMATE2271

Great study and article.

I would assume there are certain pathways and weather anomalies tied to continental and ocean currents configuration, thus preferred position appear to me very likely. I would think that because it is difficult to evaluate the AMOC/THC for instance conclusions are a challenge. Btw, Screen published a study in 2013 and found a stastitical significance… Influence of Arctic sea ice on European summer precipitation

“Here we show that months of extreme weather over mid-latitudes are commonly accompanied by significantly amplified quasi-stationary mid-tropospheric planetary waves. … Depending on geographical region, certain types of extreme weather (for example, hot, cold, wet, dry) are more strongly related to wave amplitude changes than others.”

Thank you for pointing out this research and describing it clearly. And thanks to you and your group for leadership in investigating large scale circulation and extreme weather.

Now all you have to do is snap your fingers and make me understand inertial waves.

It’s good to know that we’re finally getting down to the level of detail about this issue which will help with adaptation. Of course we’re not there yet, but the latest research seems to be a giant step in the right direction.

We all look to RealClimate to keep us up-to-date.

The work of Russell et al. (2013) http://pubs.giss.nasa.gov/abs/ru00200g.html suggests that the reduction in temperature gradient with latitude continues with even greater warming and shows up in the Southern hemisphere as well by 8xCO2. http://aom.giss.nasa.gov/CO2/TSvsLAT.jpg One wonders if resonances might affect the South even sooner.

Interesting, indeed. Thanks for this summary!

Can you relate this to today’s weather news, since people have apparently already been asking if this is another “polar vortex” item?: http://abcnews.go.com/US/summer-colder/story?id=24503103

which points to the picture for July 10th at the moment (this may change):

http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/610day/610temp.new.gif

Hank; See Jeff Master’s post here for a discussion:http://www.wunderground.com/blog/JeffMasters/comment.html?entrynum=2722

This is very interesting work and directly linked to my interest in extreme weather events as they relate to mining operations and long term reclamation and water management issues.

Fascinating! Corroborating evidence about jet stream perturbations.

The observations by Dr Francis help me to understand the chaotic climactic response we are undergoing. Change may be more rapid than our ability to conclusively prove any theory.

Thanks to everyone for their efforts in helping us to understand our world.

“Francis and Vavrus (GRL 2012) argued that a reduction of the north-south temperature gradient would cause weaker zonal winds (winds blowing west to east) and therefore a slower eastward propagation of Rossby waves.”

Maybe I am getting this backwards, but shouldn’t polar amplification increase the north-south temperature gradient, rather than reducing it?

I thought there were some problems with the Barnes paper. It it really the case that there have been no changes in Rossby waves. Can we really not attribute any of the ‘stuck’ patterns that we have been seeing so far to greater amplitude of Rossby waves? If not, then what _is_ causing these increasingly stalled weather patterns?

Alfio (#9),

The poles are colder that the equator. If the poles warm faster, then the difference in temperature between the poles and the equator is reduced which means the gradient is reduced. So far, this seems to only affect the North pole.

@ Alfio Puglisi – since the arctic is colder than the equator a relative increase in arctic temperature will decrease the temperature gradient. I also got this wrong first time I read it.

Re Wili, i think the Barnes study points out that Arctic amplification can not explain trends in midlatitude weather patterns, alone. Though, the study found a significant decrease in the month October-November-December, and concludes – but this trend is sensitive to the analysis parameters. Not entirely sure what that means but i guess, more studies are needed.

This video seems to be relevant, when Trenberth made similar points.

Pole/Equator temperature difference using NCEP/NCAR surface temperature data.

http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8223/8350036681_cdc6191164_o.jpg

Where:

Arctic = 90degN to 65degN

Mid Latitude = 65degN to 25degN

And the above plots show mid lattitude minus Arctic.

That’s from an old blog post so it’s not been updated past 2012. Note the lack of change in summer, melting sea ice pegs the temperature to zero reducing sensible temperatue change.

Tangentially related…

UK Annual average rainfall data from here:

http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/pub/data/weather/uk/climate/datasets/Rainfall/date/UK.txt

Calulated as anomalies from the 1951 to 1980 average annual rainfall and plotted here:

https://farm4.staticflickr.com/3891/14457253230_dfc9e409d5_o.png

See what happens after the mid 1990s, the range shifts upwards.

#10 Wili,

There were no ‘problems’ with the Barnes paper. Dr Barnes was correct.

Francis & Vavrus 2012 didn’t manage to show what they claimed to show. What Screen & Simmonds have managed to do is identify what F&V2012 didn’t.

Barnes never said the effect wasn’t happening. She concluded that “the wave elongation reported by FV12 is at least partially an artifact of the poleward shift of the isopleths with polar warming.” Screen and Simmonds 2013 also showed that F&V2012’s method was picking up artefacts of their method.

Barnes concluded: “The Arctic is changing rapidly, and these changes will likely have profound effects on the Northern Hemisphere. This study, however, highlights that the relationship between Arctic Amplification and midlatitude weather is complex.” Which cannot be read as a dismissal of the premise F&V2012 were studying.

Thanks Dr. Coumou,

I’m sure that I’m confused here, but since the aim of the paper is partly to make some contact with the Francis et al. hypothesis, wouldn’t the appropriate wave amplitude metric to examine be the meridional extent of selected isopleths at, say, the 500 hPa level (or higher, see below)? The paper examines reanalysis output of height anomalies averaged over a fairly broad swath across the mid-latitudes and selected regions, whose relevance is a bit less intuitive for me with respect to what Dr. Francis and others are postulating.

Just my $0.02 for discussion purposes, but there are still a lot of dynamical mysteries relating to the issue of Arctic sea ice/mid-latitude weather variability. For example, the decreased pole-to-equator temperature gradient discussed in the post is primarily expressed close to the surface (and manifested seasonally), whereas the opposite situation is true near the tropopause (where the upper tropical troposphere warms up much more than the polar tropopause regions). It’s not obvious, to me at least, why the mechanisms controlling the lower layer thickness anomalies should win out when talking about wave propagation along the Polar jet. The dynamical trends in the Southern Hemisphere, for example, seem strongly linked to ozone trends that are occurring much higher up in the atmosphere. Moreover, although the vertical gradient in east-west wind is slaved to the pole-to-equator temperature gradient in order to obey the thermal wind balance, the vertical gradient in north-sound wind depends on east-west temperature gradients, which could be important when thinking about regional and basin-by-basin trends.

If the underlying mechanisms were “simple” in that they were elegantly connected only to low level temperature gradients, CMIP5 should have no problem simulating with trends in the prevailing wave propagation characteristics.

Since the observations and simulations of propagation changes are equivocal, the underpinning theory not well-established, and the whole hypothesis focuses on the wintertime mid-latitudes (that exhibits very large unforced temperature variability), any dialogue about climate-wintertime weather connections should probably keep in mind the closing sentences from the Wallace et al. letter in Science here : “…But to make it the centerpiece of the public discourse on global warming is inappropriate and a distraction. Even in a warming climate, we could experience an extraordinary run of cold winters, but harsher winters in future decades are not among the most likely nor the most serious consequences of global warming.”

From the “why didn’t I think of that” department, the fact that this obvious relationship between high-amplitude waves and extreme weather wasn’t yet documented statistically makes for the easiest paper project ever. It’s like 101-type stuff. Kudos to them for seizing the opportunity.

However, and I think this RC post also alludes, I’m left quite wanting on how little ‘implications’ the research leaves us with. I realize it may not have been the focus of the paper, but ‘everybody’ wants to know what exactly is going to be the result of greater differential Arctic warming. Will it be weaker/zonal waves, or “high amplitude quasi-stationary” waves?

But, while we’re on the subject of intuitiveness– isn’t it hard to make a case for “high amplitude” quasi stationary waves? I mean, they rarely are stationary, with the exception of cut-off lows, and with those there’s much less room for ‘extreme’ weather seeing as they often modify in terms of temperature and don’t provide adequate breeding grounds for tornadoes nor hurricanes (at least on the trough side).

And, when viewed in another light, doesn’t this research continue to cast a pall on those who wish to insta-denigrate those who would suggest that ‘The Science’ might be unsettled toward conclusive statements on future Tornado/Hurricane climatology..?

Thanks prok and Chris R for those illuminations. I would also love to see Chris C excellent points at #16 addressed. My first guess is that it is the great amount of warming in the lower Arctic lower atmosphere that changes the height along which the jet stream flows. Temperatures gradients higher in the atmosphere would have less of an effect, I would think. (But, need I add, I’m no expert.)

– See more at: https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2014/07/rossby-waves-and-surface-weather-extremes/comment-page-1/#comment-571957

No. Say to make numbers up the poles are zero C and the middle of the planet is 70C. Difference is 70C

Then we get warming with polar amplification.

… the poles are 4C and the middle of the planet is 72C; diff. is 68

….9C and 74C, diff. is 65

….14C and 76C, diff is 62

and so on

The poles are warming faster, and the average difference between the poles and the middle of the planet is lessened.

Not a realistic example, just a thought experiment.

A lecture of Jennifer Francis about her hypothesis. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4spEuh8vswE

Chris, Jesper, Hank, thanks for the explanation. In hindsight, it was blindingly obvious…

Does Prof. Frances’ model work for the southern hemisphere? My impression is that it is specifically oriented toward the northern hemisphere. I hear that NZ is currently experiencing a rather extreme ‘stuck’ pattern. If such stuck patterns are also increasing in the southern hemisphere, don’t we need another mechanism to explain it than we do for the northern hemisphere?

…Stupid question: IIRC, average atmospheric humidity has risen by about 6%. Wouldn’t that have an effect on how everything in the system behaves? Could this be part of the explanation for increasingly ‘stuck’ systems? In other words, do heavier systems (laden as they are with more water vapor) tend to move more slowly?

this presentation:

http://www.fields.utoronto.ca/programs/scientific/10-11/biomathstat/Langford_W.pdf

has some worrying implications if the ferrel cell completely disappears..

what then will the weather be?

of more concern is the bifurcation implying abrupt climate change is in the offing …

Arctic Warming and Increased Weather Extremes: The National Research Council Speaks

Wii (22): “Do heavier systems (laden as they are with more water vapor) tend to move more slowly?” – thye would be heavier only if the air mass is “ladden” with water droplets. If water vapour remains as water vapour, i.e. as gas – then the air with more water vapour is LIGHTER- the average molecular mass of water molecule is 18, while the average weight of molecule of air should be around 28. But then again if the other air mass is also more humid these increases in humidity would at least partly cancel each out as it is the relative difference in density that matters.

Ah, I see that water vapor is actually _less_ dense than dry air. As Gilda Radner used to say, “Never mind!”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_vapor#Water_vapor_density

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3FnpaWQJO0

Maybe it’s just me but there seems something wrong with the tendency over many years for surface thermal surface lows to form cyclonic “rotten centers” beneath subtropical Rossby ridges. The idea has always been that these ridges are salients of tropical air moving northward aloft and they are supposed to be cooling and sinking. So how in this regime do you get monsoonal moisture and warm sea surface anomalies moving north as is happening right now off California?

The obvious answer is that all that sunshine bakes the surface so much that convecting air overmatches the sinking pressure and forces the subsidence to the edges. That notion works pretty well over land which is where monsoons are supposed to be, but the current rascal is offshore and it is a tongue rather than a circular cyclone and its moisture is being entrained in the macro anticyclonic flow and flung eastward across the Klamaths and the Rockies.

Just noticing.

Also just checking to see if perchance the Berlin Wall has come down.

> water vapor is actually _less_ dense than dry air.

Fun facts from physics: the Wright Brothers made that discovery — after flying at the wintertime North Carolina beach, they packed up and went home. The next summer in Ohio, their aircraft didn’t fly. They figured it out.

Thanks, Hank and Piotr.

John Abraham now has something on the subject of the main post over at Skeptical science:

https://www.skepticalscience.com/global-warming-extreme-weather-jet-stream-waves.html

mati (#23)

This notion of an equator-to-pole Hadley cell is quite implausible in my mind for a planet exhibiting Earth-like rotation rates. Such a state would require enormous angular momentum dissipation of the upper-level flow; in the current climate, twin constraints of near angular momentum conservation and the thermal wind equation demand latitudinal confinement of the circulation. You don’t need to appeal very much to the baroclinic instability that occurs in the mid-latitudes to arrive at this conclusion, even if it’s a critical part of Hadley cell termination in the real world. There are more compelling ways to start thinking about equable climate dynamics, but I don’t view any of this as particularly relevant for the “small” amounts of global warming we’re talking about in the 21st century.

#22–“…Does Prof. Frances’ model work for the southern hemisphere? My impression is that it is specifically oriented toward the northern hemisphere.”

(See more at: https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2014/07/rossby-waves-and-surface-weather-extremes/comment-page-1/#comment-573093)

I wouldn’t have thought so, since the Southern sea ice isn’t crashing, and Antarctic warming is (barring the peninsula) mostly still small enough to be hard to detect. Therefore the preconditions for the posited effect don’t exist in the Southern Hemisphere–despite the situation in NZ that you refer to.

Yet more fun facts from flying:

A standard pilot’s phrase for reduced aircraft performance is “high. hot, and humid”. They refer to high altitude, hot temperatures, and high humidity, all of which lead to lower air density. Lower air density means less lift from the wings.

The 1940’s seem to have experienced a similar period of arctic amplification. Given that many of the regions covered by this work will have fairly good data in this period, is it possible to see similar processes back then?

“Bob Loblaw says:

17 Jul 2014 at 6:38 PM

Yet more fun facts from flying:

A standard pilot’s phrase for reduced aircraft performance is “high. hot, and humid”. They refer to high altitude, hot temperatures, and high humidity, all of which lead to lower air density. Lower air density means less lift from the wings.”

In prop aircraft it also means less thrust from the prop for the same reason.

I recall after a summer of flying lessons flying on a frosty morning and wondering what they had done to the engine! The takeoff distance was shorter and the climb out rate was impressive compared with earlier in the year.

Phil:

Yes, you’re right. A prop gets its pulling power from the same “lift’ mechanism that a wing does.

I did my flying training in Ottawa, close to sea level, mostly in winter. I was used to getting off the ground in about half a 2000′ runway. When I moved to Calgary (4000′ ASL) and started flying in summer, I wondered if I was going to get off the ground before I ran out of space on a 4000′ long runway…

Bob and Phil:

Facts nicely handled and integrated into Peter Heller’s The Dog Stars, which is in part a climate change novel (though his Apocalypse–yes, its a post-Apocalypse novel–is mostly due to super-flu.) There’s a scene in which the protagonist has to get his vintage Cessna out of an extremely tight place… though from this review you’d never know what a large part of the story flying is:

http://www.npr.org/2012/08/07/157431750/dog-stars-dwells-on-the-upside-of-apocalypse

Anyone who wishes for civilization to have any chance at dealing with the Climate Crisis we currently face should really look at this Indiegogo campaign.

https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/launch-the-climate-mobilization#gallery

I am not at this time nor have I ever in the past been associated with the organization in question.

The aircraft lift stuff is fascinating. Johannesburg, South Africa is a relatively high-altitude airport and I remember the odd time feeling that the poor 747 was battling to get of the ground. The place has extremely dry (though not super-cold) winters, so I should remember to plan my future departures from there for winter :)

Thanks once again to RC for making new research accessible.

Fascinating. If they could load this into a 3D visualization movie it would be really cool.

The Antarctic has the recurring ozone hole which is a much more pronounced and regular feature of that region than anything in the way of ozone depletion that happens in the Arctic. One net effect is a reduction of ozone all year compared to the north. Ozone strongly absorbs radiation. The ocean surrounding Antarctica allows the most powerful ocean current and powerful winds to in comparison to the Arctic, isolate Antarctica. People would need to keep things like this in mind when wondering why “polar amplification” doesn’t affect both poles equally.

Since Frances is the first scientist who speaks on this video, it seems relevant to post it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c3XpF1MvC8s

I think if someone were to monitor the changes on the PNW coast here in Tofino British Columbia Canada…on Vancouver Island’s west coast…over the last two years..With the jet stream much further north, warmer night time lows, the reduced wind events off the ocean, the much warmer ocean water( surfers are wearing summer suits much, much sooner now)…the fact that we are not getting the wet fog events…and record breaking temperatures all year 2014…but mostly there is no wind..no heavy rains..no storms. Now I’ve only lived here twenty years, and out here we all watch the weather cause there’s usually so much of it…and our industries are dependent on the weather…well, it’s pretty darn strange. Might be due to these wind events…

Thanks to COBob at robertscribbler’s for this:

“Trapped atmospheric waves triggered more weather extremes”

08/12/2014 –

Weather extremes in the summer – such as the record heat wave in the United States that hit corn farmers and worsened wildfires in 2012 – have reached an exceptional number in the last ten years.

Man-made global warming can explain a gradual increase in periods of severe heat, but the observed change in the magnitude and duration of some events is not so easily explained. It has been linked to a recently discovered mechanism: the trapping of giant waves in the atmosphere.

A new data analysis now shows that such wave-trapping events are indeed on the rise.

https://www.pik-potsdam.de/news/press-releases/trapped-atmospheric-waves-triggered-more-weather-extremes

Climate Central now has a piece helping to explain Rossby Waves for those who haven’t followed the science lately.

http://www.climatecentral.org/news/whats-a-rossby-wave-17936