by Jim and Rasmus

NOTE: The authors of the book are following this post. If you have questions on this broad topic, ask them!

In the big, wide-ranging world of global change effects, one would be hard pressed to find a topic that is more important–or of more interest to more people–than effects on human health. And in science, one can sometimes also be pressed to find books that smoothly integrate technical knowledge with the experiences and needs of human beings.

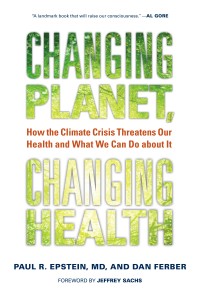

So, when you have someone with a lifetime of hands-on experience and academic training in international environmental health, describing the actual and potential impacts of global changes on the health of individuals, societies, and ecosystems, then you have something well worth paying attention to. This is certainly the case with Changing Planet, Changing Health, a new book from the University of California Press, authored by Paul Epstein and Dan Ferber, physician and writer, respectively. Written for a general audience, it deals with a number of current, and potential future, effects of global change—with an emphasis on climate change–on various health-related issues.

Senior author Paul Epstein has a strongly holistic/synthetic health perspective. Accordingly, the book is very wide ranging topically, covering issues from the discovery of the puzzling roots of cholera’s epidemiology, to the effects of large storms on the behavior of the insurance industry, to the social disruptions arising from hurricanes and warfare, to the roots of the problems with the global economic system–and much in between. The book does an outstanding job of connecting many otherwise disparate issues. These topics are all described in simple prose–there are no mathematics or model expositions, few acronyms and little jargon, etc. For these and other reasons, this book is an important and accessible contribution that many will want to read, and which many others really should.

Many of the discussions depict scenarios that are already happening, or could happen in the future, not necessarily what is likely to happen. That is, they provide examples of some possible effects, not an exhaustive attribution-oriented discussion of cause and effect, nor a model-based attempt to weigh future likelihoods of occurrence. The book is structured around chapters which integrate a particular climate change element’s effect on one or more health issues, often involving a personal story of some type. These situations include, for example, the discovery of the changing epidemiology of malaria in East Africa, crop disease and insect attacks in the United States, and the plights of the poor in Honduras.

This synthetic viewpoint stands in contrast to the narrower, reductionist perspective which permeates much of current medical science (or perhaps science in general). Accordingly, there is a short synopsis of the systems theory perspective in biology that was a central concept of the seminal work of Ludwig von Bertalanffy in the mid-20th century. It is also not surprising that the book extends the human health theme to the broader topic of system health in several places. In fact, two of the 13 chapters specifically address ecosystem stability issues, using disruptions of marine and forest ecosystems as examples, topics which may or may not have obvious ties to human health issues.

Relatedly, the book returns at several points to the general concept of cumulative effects. This first appears in a discussion of how ecologist Richard Levins of the Harvard School of Public Health influenced Epstein’s thinking on public health. It shows up later in discussions of the similar ways that plant and human pathogens’ virulence depend on the base health state of their hosts. This leads directly into a discussion of the spread of soybean rust throughout the world in the late 20th century, with its potential to greatly reduce yields and hence affect human food supplies. The idea returns yet later in discussions of the ongoing, multiple health stresses experienced by the rural poor in Honduras, making them less able to handle the effects of any additional stresses, such as those resulting from environmental disasters like Hurricane Mitch in 1998. This latter case speaks more generally to the susceptibility of the poor in general.

There are also discussions of potential surprises. For example, they describe the unexpectedly high amounts of beetle herbivory in soybeans in response to elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide, as evidenced by FACE experiments. Another example discusses ragweed pollen, a very important hay fever and asthma allergen. They describe research showing that the quantity of ragweed pollen produced in doubled CO2 environments is increased significantly (61 percent), not because of large increases in size (~ 10 percent) but rather (apparently) due to a changing internal allocation of resources. Life history characteristics of the genus might reasonably predict this result, and there are many factors in the real world that could alter it. But it still serves as a useful example that could otherwise fly completely under the radar.

While the use of ecosystem complexity to illustrate the potential for surprises is certainly valid, it can also be a double edged sword. There will very likely be surprises that have unexpectedly positive results as well, and the overall balance between positive and negative is highly uncertain. My (Jim) one criticism is that I would like to have seen this this point made, with reference to experimental or model results. The plant ecology and/or agriculture discussions would have been a good place to do so, given the complexities/uncertainties involved. The authors’ strongest points are arguably those dealing directly with well-defined and direct human health concerns having demonstrated relationships with well understood climate dynamics.

Several important points of the book relate to biological thresholds. These are ubiquitous in biology at all scales and are illustrated nicely in several places; a particularly good example is the effect of temperature changes on malarial epidemiology. Malaria is caused by species of single-celled parasites in the genus Plasmodium, vectored by mosquitoes primarily in the genera Aedes and Anopheles between many vertebrate hosts, including humans. Debilitating to lethal in effects, the disease also comprises a fascinating scientific story. This includes for example, the effects of weather/climate on the population dynamics of rapidly reproducing, cold-blooded organisms, and the epidemiology of disease spread (and interesting textbook cases in genetics and evolution as well).

Epstein and Ferber describe how small changes in temperature can lead to large changes in malarial dynamics. This is a function of both insect and parasite life cycle development time–both of which are typically non-linear. These in turn have non-linear effects on malarial epidemiology, via changing spatial patterns of temperature and precipitation combined with the spatial pattern of human populations and the genetic resistance to malaria therein. So, full Plasmodium falciparum development that takes 56 days at 18 degrees C, but only 19 days at 22 degrees, has very significant implications for a mosquito host that lives only 3 weeks maximum: it allows the full development of malarial parasites which are not possible at the lower temperature. The insect population dynamic also matters, which in an aquatic breeder like mosquitoes, will be a function of both temperature and the existence of water reservoirs having a 3+ week lifetime, which in turn are a function of precipitation intensity and frequency. Insect population threshold effects are also discussed in a later chapter devoted to the topic of tree mortality and bark beetle dynamics in western North America.

The forest that really should not be missed for the trees here, is the importance of these non-linear dynamics in response to climate change. Considering that many biophysical systems are webs that are considerably more complex than the examples provided, it takes little imagination to realize the potentially high levels of unpredictability that are quickly reached. And this should give any reasonable person–and society–concern about the consequences of forcing the climate into a state that is without precedent in modern society. Science is difficult enough when equilibrium states are the study focus, let alone when strongly forced and thus, transient.

Environmental health also includes non-biological stressors, such as environmental chemicals, food, water and air quality, social upheavals, etc. Epstein and Ferber address these broader issues as well. For example, one chapter is devoted entirely to air quality/composition and its effects on a wide ranging and chronic disease, asthma. They also recognize that global change is not just climatic. They describe, for example, the multiple causes of health effects in places like Honduras, resulting from the combined effects of mangrove clearing and shrimp farming, gold mining, El-Nino changes, and hurricanes, each contributing its part to an unhealthy and unsustainable condition.

The book is also not shy about engaging controversial topics or discussing the disinformation campaign. For example, Kenyan malarial epidemiologist Andrew Githeko was targeted a decade ago after his model-based predictions of the spread of malaria into the highlands of East Africa, where it is currently expanding but was historically absent due to the temperature limitations that altitude brings. Several of the tactics of denial that are well known to RC readers, are discussed. Nor are the authors afraid to discuss issues in the socio-political world that drive many of the human behaviors that are leading to climate change as well as the unequal suffering that will be experienced due to inequalities in wealth. And neither are they reluctant to address the multiple social and environmental costs of fossil fuels, such as coal. Once trained in making connections across disciplines, well, the habit tends to express itself.

In the discussions of climate per se, there are a few minor inaccuracies in an otherwise sound discussion of what is known. However, none of these has any bearing on the bigger picture portrayed. For instance, the book discusses the (essentially non-existent) effect of El Nino Southern Oscillation on the Gulf stream; it is possible that the authors actually had the ocean currents off the Peruvian and Equatorial coasts in mind. There is also a misconception in the book’s introduction about the strength of a greenhouse and the thickness of the glass panes, but this does not translate to the greenhouse effect. This is, however, noted later in the book, so the inconsistency is just a glitch. The book also asserts that global warming will lead to more storms, which is still a disputed issue. The situation regarding glaciers on Mt. Kenya is probably more complicated than just a question about temperature – changes in precipitation pattern will also affect their mass balance.

The authors are critical towards certain multinational corporations, discussing for example the role of ‘economic hit men’ (e.g. John Perkins). And although the book covers many topics, it does not discuss population growth, and it touches on communication issues only lightly in discussing why the world has so far failed to act on climate change. This is somewhat ironic, given that the book is one of the best examples we have yet seen regarding the effective communication of climate change issues. It suffices to mention “Climategate”, “Wikileaks”, and social networks (in recent developments in Northern Africa) to understand the power of information/disinformation and communication, in molding public opinion.

The book also mentions Norway as a shining example regarding the tackling of climate change, but the world is more nuanced; Norway also pushed for more oil drilling in the Arctic, and is involved in tar sands in Canada, as well as oil exploration in Libya. Also, much of the surplus that Norway gains from pumping oil is invested into the same kinds of corporations as those Epstein and Ferber describe as part of the problem.

But there is much more to be learned from the book than just the various technical issues discussed. Just as important is the very evident concern with human welfare and justice; these have clearly motivated a very large part of Epstein’s life work, as well as several of those discussed in the book. One particularly good example is the rather amazing story of the Honduran doctor Juan Almendares and his lifelong dedication to the welfare of rural and/or marginalized people there. The importance of this human aspect in solving the impending global climate change problem is most certainly not to be overlooked, and it in fact forms a kind of subliminal undercurrent upon which the various technical discussions in the book all ride.

Paul Epstein and Dan Ferber have created in this book an outstanding synthesis of climate change and human/environmental health concerns. It is born of a lifetime’s work, and addresses topics that will potentially affect a very large number of people. This is a great and needed contribution and we recommend it without reservation.

Does anyone know of any studies about the effect of chronically elevated CO2 levels (per se) on breathing organisms such as myself? I’ve seen investigations on how the pores of plants are affected, and of acute, short-term exposures. But as to the biological effects of never drawing a breath of air with less than 300 ppm of CO2, I’m surprised that few have thought of looking into it.

Daniel,

Here is a real-life study on airplanes, where CO2 levels are typically between 600 and 1500 ppm. It also contains references for other CO2 studies.

http://www.boeing.com/commercial/cabinair/ventilation.pdf

Thanks for letting us know about what sounds like avery valuable resource!

Hello All,

Talk about timely! I write from climate denialist New Zealand, where the wonderful James Hansen is touring, and where I’ve had the privilege of attending a public lecture he gave and a forum on the “Future of Coal” he contributed to. (Tragically the future of coal/lignite glows brightly in NZ. I possibly should not be running down my own country, but I feel it is my patriotic duty to do so. If you’ve ever heard the expressions “Clean, green New Zealand” or “100% Pure” in connection with this backward country, then don’t believe a word of it. We have the world’s sixth highest environmental footprint, soils are washing into the ocean at an entirely unsustainable rate, our CO2 emission have increased around 35-40% since 1990, we are planning to dig up millions of tonnes of lignite and convert to diesel or fertiliser which will further double our CO2 emissions, 70% of lowland lake and streams are seriously polluted with farm run-off, we are now importing over a million tonnes of palm-oil kernel feed for our increasingly intensive dairy and livestock farming practices when a few years ago we imported no cattle feed at all, our public transport system is failing in our sprawling cities and we are planning to build billions of dollars worth of new motorways. We get away with our clean green image, and that’s actually all it is, it’s an advertising slogan with the same underlying intellectual honesty as “Persil washes whiter”, because of our low population, our temperate climate and our beautiful and apparently empty countryside and wild places. As a consequence of which, when James Hansen was invited to say what he actually thought about New Zealand’s record, he was, as he always is, honest, and he was highly critical. Which caused the CEO of our Nationalised and shortly to be privatised coal company, Dr Don Elder (he’s an engineer) to have an apoplectic fit and petulantly dress down one of my most admired Americans with “Who do you think you are coming to New Zealand and criticising us like this” It was appallingly rude, and was the display of a man whose cocky and glib presentation looked to be the covering for a pretty shallow skin and insubstantial argument.)

At any rate, sorry about this rant, but it’s really important that New Zealand suffer some real economic consequences for its failure to live up to its carefully cultivated image, and that if you are buying products from New Zealand, you are supporting a country that is no better than yours. Tell your friends. If New Zealand were to change, I will tell you.

In regard to this particular topic, then, I am a local medical practitioner, and over the last few years, myself and some of my medically qualified colleagues and other people with the professional qualification of “Dr” have so signed their letters to our local (climate denialist) newspaper, the Dominion Post. But we have come under fire from other correspondents for doing this, what right does our medical qualification give us, they complain, to suggest expertise in climate science or in any other matter other than pertaining directly to medicine. This caused one of our number, Dr Scott Metcalfe, to send this letter, signed by several of us.

(Italic) Doctors’ responsibility

Rex Benson (Letters, May 6) misunderstands modem medical practice, which is much more than prescribing pills for individuals. Health professionals – including doctors – have a professional duty to act and press for their patients and populations, current and future, including scientifically established risks to public health. Every day we see the harm of inaction.

The NZ Medical Association’s landmark statement on health equity on 4 March (on the NZMA website) clearly mandates doctors to talk about what determines health. The longstanding ethic to ‘First do no harm’ extends to speaking out against policies and practices that harm – whether by damaging child health, widening health gaps, or escalating climate risk.

The world’s health authorities are focused on dangerous, costly and potentially irreversible climate change as the biggest health threat this century. Good medicine recognises risk and urgency and sometimes must act presumptively on emerging but incomplete information. So despite some uncertainties (inevitable with any science), the potential consequences are so calamitous and imminent that the responsible action must be to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

While New Zealand lags behind responding to the global climate crisis and fails to see the wider implications for health, many health professionals will continue to speak out.(End italic – sorry couldn’t get this to work)

Following this letter, was yet another saying how “arrogant” we are. So I wrote another letter back, poking some fun about all this nonsense. I don’t know whether it will be published, but in any case, this posting in Real Climate, with your coverage of the publication of this book, provides some much needed ammunition for us beleaguered but concerned medical practitioners here in Wellington. I hope we will be able to buy this book locally, or we may order if from Amazon, or electronic book from Apple etc. I don’t wish to comment on the substance of the book or your review, but perhaps when I’ve read it, you might like to have this 64 year old practitioner’s review and thoughts? Apologies for this rather long effort, but I thought you might be interested to hear the experiences of us concerned citizens and professionals here in what used to be called “Godzown”

[Response: No apologies needed John. And we’d certainly be interested in your thoughts, no question.–Jim]

PS Re my posting about New Zealand.

1) The environmental footprint mentioned is, of course, per capita

2) New Zealand does do many environmental things very well, and it’s not that NZ is manifestly worse than many other countries, it’s just that it’s manifestly no better. This attempt to increase the perceived value of our goods and services, in our competition with other nations, by claiming that it is better, is either unintentionally hypocritical or intentionally misleading.

While I think this book is a good idea, it seems like there would have been a better market for it 5 to 10 years ago. The general public is tiring of the “Dangers of Climate Change” scenarios these days and turning a deaf ear.

I think the article’s authors said it right when they described it as a book “..which many others really should [read]”. The question is, will they?

I had the privilege of driving a professor of medicine from Houston a couple of weeks ago. He was in town to deliver the keynote address at the Primary Care Update conference. His topic was Tropical Diseases You Need to Know About, Now. On our trips he outlined the problems as he saw them: increasing malaria across the Southern US, expansion of the dengue fever range into Southeast US, increase in cases of encephalitis and return of yellow fever in the west, increase in plague that is completely resistant to treatment (found in Madagascar) and so forth. Lovely, but he had a good attitude.

Thanks for mentioning allergy and asthma problems. I don’t happen to be allergic to ragweed, but less winter means more pollen in general.

Thanks for mentioning “Soybean rust” and insects which are additional reasons for going hungry, but droughts and floods may do us in first. The book seems to me to be soft-pedaling GW. The problems mentioned are trivial compared to a world wide drought that shuts down agriculture in the middle of this century. Such a drought that ends civilization has been discussed before in RC.

“Non-linear”ities are the thing that bites most people. They don’t understand the concept because it is mathematical. A tiny change now is not noticeable, so they dismiss the whole issue of GW. But the tiny change is the precursor of something cataclysmic.

The “unequal suffering that will be experienced due to inequalities in wealth” may not work out the way you expect. Since money is worthless once civilization collapses, the formerly rich are in for a rude awakening. The most likely to survive may be those who are still living in the stone age. The collapse of money will have no effect on stone age people. If they are not over-run by outsiders looking for food, they may continue as they were until some of them migrate out much later.

[Response: They’re not soft-pedaling climate change effects at all, and they discuss the effects of drought and severe drought in several places. There’s no evidence for what you suggest regarding global drought. The earth could also get hit by a giant meteorite. Please stick to the reasonable.–Jim]

Thank you for the review. Sounds like an important and timely book.

It constantly surprises me how infrequently the word ‘health’ appears in mainstream media and blog discussions around climate change. For better or worse, people in the real world generally don’t care about complicated abstractions like CO2 ppm, temperature anomalies, attribution of extreme weather events, and ecosystem degradation.

They do care about the physical and mental health of themselves and their families. The time when climate change gets widespread recognition as a public health issue is the time when we’ll see serious political moves to mitigate and adapt to the problem.

[Response: Good points all. This lack of attention was in fact a main reason for the post, and Paul Epstein discusses exactly the same incredulity at the lack of attention when he went to the earth summit in Rio in the early 1990s, and how that inspired much of his later work on the issue. If you can’t get society motivated by human health considerations, then forget it, it’s all over in terms of ever doing anything significant to address the problem. Just look at the number of comments on this post so far.–Jim]

spyder,

Did the professor mention what he felt was the cause of these recent increases? It has been reported by the CDC(at least for malaria) that the increase in infections has been due to person travelling to infected areas. Any comments?

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21508921

[Response: Yes, most of the US malaria cases for 2009 (and presumably previous years) were due to traveling into endemic areas. However, the authors devote an entire chapter to the issue of the geographic spread of malaria (via the spread of the mosquito vector), using examples from Kenya, where the evidence is strong that increased temperatures have led to a geographic spread of mosquitoes from lower to higher elevations, and with it, unstable transmission (because of the lack of the genetic resistance that is more common at low elevations). They also cite similar evidence from other East African countries, and Latin America–Jim]

Dan, it’s not malaria, but mosquito borne disease has killed a couple of people in Australia following our summer flooding – not in Queensland but because of the flooding in Victoria and similar floods in the Pilbara region of WA. The people who got ill (including the 2 who died) didn’t go anywhere, the mosquitoes bred locally.

Murray Valley encephalitis has no vaccination nor any specific treatment. The only prevention measure is insect repellent.

Adelady,

I know very little about Murray Valley encephalitis except for what I just read in an NSW government report, which said it was confined to NW Australia except during times of heavy rainfall and flooding when it spreads east and south. That sounds like what has happened this year. Do you concur?

Are there signs of a possible epidemic?

Jim wrote: “There’s no evidence for what you suggest regarding global drought.”

With all due respect, I am inclined to push back on that assertion.

I suppose it depends what you mean by “global drought”. If you mean “every square inch of the Earth’s land surface is experiencing drought”, perhaps you are right.

But if “global drought” means increasing frequency and duration of intense drought conditions and/or steadily increasing chronic aridity in the American southwest, Australia, Russia, China, Africa and South America, all occurring at the same time, and significantly reducing the productivity of some of the world’s most important agricultural regions, then I would say the evidence for that is that we are already seeing it happen, now.

[Response: It wasn’t my term or concept. We can certainly discuss drought trends and effects on agriculture. We’re just not going down the road of wild speculations about the end of civilization, stone age etc. That’s my main point.–Jim]

Without speculating wildly about the end of civilization, one question has occurred to me: if we eventually have to downshift to a somewhat less high-tech, long-supply-line mode of life, how can we maximize the usefulness of the huge advances in medical knowledge, technology, and technique that we have achieved? Might it not be useful to start thinking about what a relatively resource-constrained medicine but still scientifically informed medicine might look like?

Jim and Rasmus: Paul Epstein and I appreciate your thoughtful review, and are glad that you highlighted our emphasis on a synthetic, systems-based approach.

I’d like to respond to the point Jim made about the effects of ecosystem changes on human health. I agree that ecosystems can change in surprising ways in response to climate change; that these are very difficult to predict, and that in certain cases, regional changes could be judged as positive.

In the case of agriculture, for example, it is possible that as some northern regions warm (near the U.S.-Canadian border, for example), that crop production could rise regionally. But overall, we believe that the cumulative effects of climate change on agriculture—the increased insect damage, harm to crops from heat, loss of irrigation water from melting mountain glaciers, extreme weather and flooding (as we’re seeing in the Mississippi Valley right now), and a rise in weeds and plant diseases will lead to lower average crop yields. This of course could harm food security, or lead to malnutrition or even, in some vulnerable areas, famine.

More generally, our discussion of the effects of ecosystem change on human health was anecdotal. It had to be. Knowledge of these effects is incomplete. That said, we think it’s important to combat the reductionist thinking that has led many people, including some scientists, to focus only on the risks that can be clearly documented, and not on the murkier yet potentially larger risks that arise when stressors accumulate and push ecosystems to the brink.

This is why we covered health risks such as intestinal and neurological problems from red tides and how climate change in the U.S. West has contributed to forest fires, causing smoke that aggravates respiratory and heart disease. More generally, healthy ecosystems, including the managed ecosystems we call farms, help supply us with clean air to breathe, pure water to drink and nutritious food. The links are intuitive, if incompletely documented, and we ignore them at our peril.

Finally, in Changing Planet, Changing Health, we also lay out a suite of technology and policy solutions to help us move to a low-carbon economy, mitigate climate change, and thereby protect human health. Many of these solutions were carefully vetted in studies that Paul and many colleagues conducted, with the goal of identifying solutions that offer maximal benefits and minimal damage to human health and to the environment. At this point, we need to choose such solutions carefully. We can no longer afford to miss the forest for the trees.

[Response: Thanks Dan, very nicely stated. The point about the need for cumulative, system-wide cause and effect analysis is very important and I fully agree with it. The problem of course, is in the doing–Jim]

Matt (#9), it surprises me as well that health is mentioned so infrequently in media coverage of climate change. It’s one reason we wrote the book. And I agree that ordinary people care about the physical and mental health of themselves and their families more than abstractions about climate change.

I share your hope that when people connect climate change with their health and the health of their children and grandchildren, that it will help spur real change. But, alas, I don’t think it’s quite that simple.

Since we didn’t talk much about communicating climate change in the book, as Jim and Rasmus point out, I’ll share a few of my thoughts here. (I’m speaking only for myself and not for Paul Epstein.) I think there’s no one-size-fits-all approach that will move everyone to action. Some people pay a great deal of attention to health news and information; some don’t. The ones who do can be influenced. Some care mostly about national security, and will respond more to a report by a bunch of generals and defense experts on the looming national security problem posed by climate change. Others will respond more to the threat to the forests, rivers, lakes and seas. Still others will respond only if their pastors talk about the threat to Creation. Many, many others will respond only if they stand to gain or lose money, which is why we need policies that create incentives for doing the right thing.

Then there’s the question of what will move policy makers to take meaningful steps to mitigate and adapt–or even to drop the denial and recognize reality. Some are–but most of them are working at the local or regional level. In Washington, money has contaminated the system to such a degree that I think it will take a very large groundswell of public support to dislodge the big power players and push through the reforms we need. Politicians tend to move when they’re scared they’ll lose their jobs, and often not before then.

About a month ago, I was on a panel at the University of Illinois discussing the solutions we recommend in Changing Planet, Changing Health. A rural sociologist on the panel noted the absence of social scientists in our book and suggested that such experts might have a lot to offer in terms of understanding how to move people to action in the real world. I agree. The communications challenge is a big one–a lot of smart people have thought about it for years–and we need every possible tool at our disposal.

Dan. Epidemic? I hope not. The numbers are pretty low – half a dozen in WA, even fewer in SA and Victoria. But these were the first MVE cases for 30+ years in SA. So by comparison, it would look a bit like an epidemic on a graph. There have also been higher reports of Ross River virus and a couple of other unusual mosquito borne illnesses. But these tend to cause long term debility rather than kill you by raging infection as MVE can.

The big issue for MVE is that it’s carried by birds and there’s been a welcome explosion of water birdlife in the region. So the rule here from now on looks to be – don’t just smile when you see lots of pelicans and ibis nesting by the water, get out the repellent spray.

Dan, thanks for stopping by. Will the book be published in the UK?

Re: human health as a driver for action on climate change, I agree it won’t work for everyone. Otherwise health promotion would be easy. Most smokers know it’s bad for their health, and that knowledge on its own isn’t enough to make them stop. But the line climate activists have been taking to date is analogous to telling smokers not to smoke because it degrades the environment- other people don’t like it, it smells bad, stains the walls etc- while neglecting the argument that it kills the smoker.

The public health community does seem to be engaging with climate change as an issue, at least on this side of the pond, but the problem is that the public and politicians are not engaging with it as a health issue. Unfortunately I’m not optimistic. It will probably get widespread recognition as a serious public health problem at the same time it’s recognised as a serious national security, food security, and (possibly) immigration problem- and meaningful action will be taken, but not before avoidable adverse societal and health impacts have been incurred.

(Argh! I hate recaptcha. I didn’t see it below the preview, so I “failed” it, but I had to go back to get my text back, and then when I submitted it again it said a duplicate comment was detected. So Mods, if this is a duplicate, kill it. But why is the Say It button not down beside the recaptcha?)

I’d like to second the question posed by SqueakyRat (#14). Indeed his question can be expanded beyond medicine to most facets of a modern society. What does a sustainable society look like when it is committed to the advancement of knowledge, the best affordable medical care, the alleviation of a regional problem (like drought) with surplus from another region, etc? It’s not a bunch of self sufficient and relatively isolated communities. It still has to have cities, universities and long-distance shipping even if we try to do less long-distance shipping.

Anyway, I’d be really interested if the authors of this book have a picture in their heads of what an advanced sustainable society looks like.

Thanks!

Matt, I do think the public health approach is critically important. Many of the environmental laws we have in the states came about in large part because of concerns people had about their health. I think health is a powerful motivator for many, and we definitely want to reach them with this book. The smoking analogy is a good one in several ways. We’re dealing with an addiction — nicotine, or easy energy from oil, gas and coal — that is dangerous yet tough to beat. The wealthy industry that sells the addictive product has many politicians in its hip pocket. (This was once true about tobacco.) It has funded a public relations campaign of several decades duration to sow doubt about well-established science confirming the harm of their product. And that public relations campaign in fact includes some of the same people who used to defend cigarettes and excuse second-hand smoke.

The public health community in the United States is becoming engaged in this issue, as are leaders in the medical community. It hasn’t really filtered down to the rank-and-file doctor or nurse, though. I spoke with a medical educator recently who complained that when she tried to educate first-year medical students about the health risks posed by climate change, she got little support from her colleagues or superiors. So there’s a long way to go. But there are also a lot of positive changes happening right now, which offer reasons for hope.

And on publishing the book in the UK and other territories. We hope so and are working to make that happen.

The last IPCC report was pretty reserved on malaria, I thought. For good reasons, or out of conservatism? Do we know more now than in 2007 about the relative importance of non-climatic factors in the observed and projected spread of malaria (vector control, migration, drug resistance, insecticide resistance, land-use and other ecological changes)? Do we have projections that take adaptive capacity better into account?

http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg2/en/ch8s8-2-8-2.html

http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg2/en/ch8s8-4-1-2.html

re: 14

“Might it not be useful to start thinking about what a relatively resource-constrained medicine but still scientifically informed medicine might look like?”

I’ve thought for a long time that it would be really useful to aggregate in some place all that we know about the technologies of other eras. Instead of by some arbitrary time line, maybe by available energy sources. A life style like the 1920s with much of modern medicine, would be fantastic alternative to the Mad Max kind of dystopias that are widely imagined.

Jeffrey – It would be useful to consider how much of “modern life” in general, and the life sciences in particular are dependent on petrochemicals – it’s not all about “energy”

Very interesting stuff – thanks for posting this review.

This may be too specific of a question for here, but in recent years there have been more and more outbreaks of West Nile and forms of equine encephalitis. The first case of the year was reported earlier this week in Texas. I know these are mostly mosquito borne diseases – are they linked to shifting patterns in mosquito species distribution? Or, like with malaria in the above post, mostly owing to contact with regions where EHV-1 is endemic?

[Response: I think it’s more an issue of spread into an increasing number of insect species, and alternate hosts (birds especially) that are already endemic (at least in the first several years in the US), but I could be wrong. Some of these species can survive certain winter conditions and that’s a (potentially) critical factor as well.–Jim]

It would be really good to have a well-developed idea of where we are trying to go. It’s not easy to imagine how things will need to be.

I keep getting stuck at more mixed development and higher mean population densities in order to reduce both energy intensity and utilization rates of motorized transport. (Probably it would be most helpful, but also hard to picture happening fast enough.)

But of course there are many, many pieces to the overall puzzle.

John Munro (#4) has some highly relevant comments re the New Zealand “Clean and Green” image. From my perspective – 36 years in England and 38 years in New Zealand, it is the cultural discontinuity of a mostly British high-population-density immigration into a low-population density New Zealand that is the determinant of “world’s sixth highest environmental footprint”. The dilution by the environment of the so-easily disposed contaminants was once so great as to raise no significant concern. In more recent times, following 1 to 2% per annum immigration, the population has risen very noticeably – 3 million when I arrived in 1973 to over 4 million today – as has the vehicle density per capita, from generally one per family to two, and the level of indistrialisation, especially intensive pastoral mecahnisation.

It is very noticeable that Japanese and some Asian tourists are exceptionally careful of their rubbish disposal – a cultural feature in Japan and Singapore. If our population and industries followed their example we would have no problem to speak of.

Not that this is much relevant, but my father was diagnosed with malignant tertian malaria during the Solomons Campaign (Guadalcanal, Tulagi, Gavutu-Tanambogo, etc.) during WW2. They sprayed the base areas with copious amounts of DDT, as well as drenching their clothing and bedding in it. He still caught it.

He’s 92.

Good presentation (including Dr. Epstein) on PBS “Need to Know” tonight. It’s very interesting that diseases and pests are migrating – they used an instance of tropical fungus that appeared in the Pacific Northwest; incidents like this are becoming common. Allergens are certainly on the increase due to longer warm seasons and enhanced pollen production. (I don’t understand all the mechanics, but the facts seem to be established if you discount the fringe knee-jerk negaters.) The program tends to rerun over the weekend so you can find it on your local PBS station if you wish to view it.

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/need-to-know/environment/video-from-allergies-to-deadly-disease-feeling-the-effects-of-climate-change/9457/

John Monro:

New Zealand has a fine potpourri of climate commentary and information which you might appreciate and might make you feel less isolated. Their weekly radio show covers a lot of bases.

http://hot-topic.co.nz/

Susan, one of the better episodes of “Need to Know”. Worth noting they also had a piece on the coal mining disaster with a clip of the CEO of Massey Energy company waddling around a stage clad head-to-toe in a garish American flag outfit berating government regulators, saying that the idea that they care about worker safety more than Massey was as crazy as the global warming theory. A. sobering and revolting spectacle of bloated parochial arrogance.

“There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that ‘my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.” Isaac Asimov

Is there a link in their book to disease vector information? I would be interested in the duration and loci of disease outbreaks. I am also searching for information on animal and insect pathology changes. Are we, as a species causing other species to adapt specifically to the environments we create? Altering their social dynamics, reproductive tendencies, lifespans etc.

[Response: There are a number of citations in the book relative to the infectious diseases that they discuss (cholera, malaria, lyme disease, dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fevers, etc.) and also on work relating climatic extremes to disease outbreaks. Two excellent places to start, for all diseases, are at the CDC website:

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/ (morbidity and mortality weekly report)

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/ (journal of emerging infectious diseases)

Hope that helps–Jim]

Re: #1; direct CO2 health effects

From Hank, long ago (B-grader, but interesting): http://www.ias.ac.in/currsci/jun252006/1607.pdf

I clicked to the book’s website, and this was the penultimate sentence of the promotional descriptive paragraph:

‘In clear, accessible language, it also discusses topics including Climategate, cap-and-trade proposals, and the relationship between free markets and the climate crisis.’, which sounds much more ‘political economics’ than the science/health/AGW/environment book described in the post?

The last sentence of the promo para:

‘Most importantly, Changing Planet, Changing Health delivers a suite of innovative solutions for shaping a healthy global economic order in the twenty-first century.’ Those two sentences describe a different book to that described overall in the post?

[Response: The book is very wide ranging. The review was already kind of long and so I omitted mentioning that the authors also discuss the causes of the current state of affairs, and provide some proposed solutions and examples of what individuals can do, or are doing, to help. This approach is appropriate given the nature of environmental health, which is to diagnose and treat the problem, and then take action to prevent recurrence. And the causes involve these socio-political-economic aspects.–Jim]

Ah, ok, had it been a book concentrating more on layman-accessible science, and less on political economics I would have been more interested,

[Response: It’s still much heavier on the former than the latter.]

but having browsed through his other writings from the HMS website and letters to the NYT and so on I see he has plenty of strongly held opinions in areas well outside his undoubted qualifications in environment and health.

I also noticed (in the other writings) a perhaps one-sided naivety that you remark on in your review, you mention issues like the Gulf Stream, storms, Norway, African glaciers, where he tends to the black and white, which for me detracts from the level of trust I’d have when he’s writing about what he knows.

Perhaps unfair.

[Response: Try to keep in mind that it’s very difficult to write really wide-ranging stuff and also get all the technical details right on the various topics. This is a book where you really want to focus mainly on the bigger picture, trying to connect dots rather than to scrutinize each individual dot.–Jim]

Hot Rod (#33): We certainly make an argument with this book, but it’s one we believe is well-grounded in science and documented fact. As you know, not all expertise comes from academic training programs–much is learned on the job by collaborating with experts in other fields. For the past decade Paul Epstein has collaborated extensively with scientists with a wide range of expertise, as well as with economists and leaders in the banking and insurance industries, to help identify practical, real-world solutions. This work includes a number of in-depth studies to vet many of the solutions we propose in this book, all of which are available for download at the Center for Health and the Global Environment website: http://chge.med.harvard.edu/publications/reports/index.html. If you’d like to dive in, I suggest the various life cycle analyses of energy sources like oil and coal, and especially the report, Healthy Solutions for a Low Carbon Economy. We draw on all this work and additional research to propose solutions that range in scale from the individual to the global. Thanks for your interest in our book.

One concern I have is there seems to be little or no discussion of possible health benefits of a warmer climate. This leaves such work wide open to the attacks of the denialists. What are possible benefits? For those of us who live in high latitudes, these might include a shorter flu season, longer growing seasons, more rain in some places, and the health benefits of spending more time outdoors. To be credible, both potential negative and positive effects need discussion.

Great post.

And to add to it….there is the issue of warmer weather (which we would expect in a warming climate) contributing to higher violence rates. This has been studied for years, well before CC became a big topic. And some have also studied the impact of other CC effects, such as severe storms, floods & droughts on increasted violence, due to the increased psychological stress.

And then there are the heat and collective violence riots) studies.

There is also the issue of the increased flooding caused by CC spreading toxic and hazardous waste and chemicals around & harming health, as well.

Is there an entomologist in the house? I am wondering about research on the relationships between a warming climate and insect populations (in general, but of course there are many health ramifications.) We have been experiencing a very wet spring in New England (USA) followed by a period of well-above-average heat and humidity. I have lived at my address for 12 years, and clearly notice a change in the phenology of blackflies (a major annoyance, a mental health threat!) — their peak arrives about two weeks sooner than previously, and their numbers, along with mosquitoes, June bugs, and others have been through the roof this season. Ticks are also more numerous and earlier. Do insect populations show trends with CO2 as well as temperature? Do we have a prognosis with the expected changes this century and beyond?

While I do not doubt our species’ ability to survive whatever may come our way, at least in some numbers, I do wonder about the quality of life, and insects could figure heavily in that.

Can’t say I’ve read the book yet (on order) but could the authors, or anyone else, comment on the 300,000 deaths/year attributed to global warming in the Human Impact Report published by the Global Humanitarian Forum in 2009? If such a figure can be supported it should be made more use of.

Well, I have not read the book as yet, and sadly only came to read the article just today, but I am happy to see systems theory and Bertalanffy mentioned. He is considered the father of modern systems science.

I worked with Dr. James Grier Miller from the late 80’s and throughout the 90’s who had based much of his work in Living Systems Theory (LST) on Bertalanffy.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Living_systems_theory

Miller was also worked in cybernetics and behavioral science (actually he coined the term).

http://projects.isss.org/James_Grier_Miller

For those interested I developed a health definition of interacting systems.

http://ossfoundation.us/our-view/health-definition

The version of the health definition on this page is an older version but applicable. I have further developed it and will have the new version hopefully online later this year.

Dynamical system interaction has struggled somewhat with what is health. Even modern psychology has struggled with what is health? The definition applies to general system interaction as well as subsystem and parent system interaction. It applies to physical and non physical systems as well.

The Lancet is speaking out about climate change vs human health. h/t Sime.