At Jim Hansen’s now famous congressional testimony given in the hot summer of 1988, he showed GISS model projections of continued global warming assuming further increases in human produced greenhouse gases. This was one of the earliest transient climate model experiments and so rightly gets a fair bit of attention when the reliability of model projections are discussed. There have however been an awful lot of mis-statements over the years – some based on pure dishonesty, some based on simple confusion. Hansen himself (and, for full disclosure, my boss), revisited those simulations in a paper last year, where he showed a rather impressive match between the recently observed data and the model projections. But how impressive is this really? and what can be concluded from the subsequent years of observations?

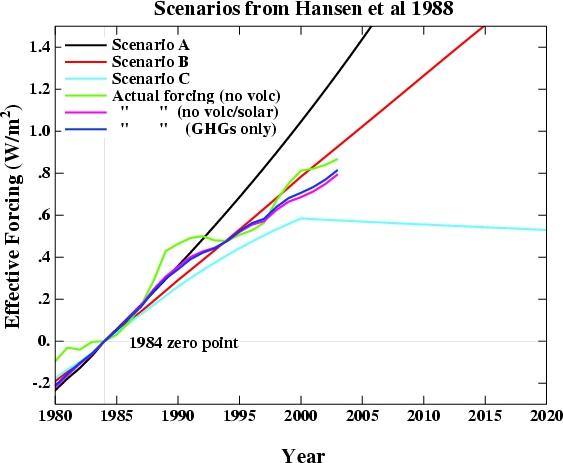

In the original 1988 paper, three different scenarios were used A, B, and C. They consisted of hypothesised future concentrations of the main greenhouse gases – CO2, CH4, CFCs etc. together with a few scattered volcanic eruptions. The details varied for each scenario, but the net effect of all the changes was that Scenario A assumed exponential growth in forcings, Scenario B was roughly a linear increase in forcings, and Scenario C was similar to B, but had close to constant forcings from 2000 onwards. Scenario B and C had an ‘El Chichon’ sized volcanic eruption in 1995. Essentially, a high, middle and low estimate were chosen to bracket the set of possibilities. Hansen specifically stated that he thought the middle scenario (B) the “most plausible”.

These experiments were started from a control run with 1959 conditions and used observed greenhouse gas forcings up until 1984, and projections subsequently (NB. Scenario A had a slightly larger ‘observed’ forcing change to account for a small uncertainty in the minor CFCs). It should also be noted that these experiments were single realisations. Nowadays we would use an ensemble of runs with slightly perturbed initial conditions (usually a different ocean state) in order to average over ‘weather noise’ and extract the ‘forced’ signal. In the absence of an ensemble, this forced signal will be clearest in the long term trend.

How can we tell how successful the projections were?

Firstly, since the projected forcings started in 1984, that should be the starting year for any analysis, giving us just over two decades of comparison with the real world. The delay between the projections and the publication is a reflection of the time needed to gather the necessary data, churn through the model experiments and get results ready for publication. If the analysis uses earlier data i.e. 1959, it will be affected by the ‘cold start’ problem -i.e. the model is starting with a radiative balance that real world was not in. After a decade or so that is less important. Secondly, we need to address two questions – how accurate were the scenarios and how accurate were the modelled impacts.

The results are shown in the figure. I have deliberately not included the volcanic forcing in either the observed or projected values since that is a random element – scenarios B and C didn’t do badly since Pinatubo went off in 1991, rather than the assumed 1995 – but getting volcanic eruptions right is not the main point here. I show three variations of the ‘observed’ forcings – the first which includes all the forcings (except volcanic) i.e. including solar, aerosol effects, ozone and the like, many aspects of which were not as clearly understood in 1984. For comparison, I also show the forcings without solar effects (to demonstrate the relatively unimportant role solar plays on these timescales), and one which just includes the forcing from the well-mixed greenhouse gases. The last is probably the best one to compare to the scenarios, since they only consisted of projections of the WM-GHGs. All of the forcing data has been offset to have a 1984 start point.

Regardless of which variation one chooses, the scenario closest to the observations is clearly Scenario B. The difference in scenario B compared to any of the variations is around 0.1 W/m2 – around a 10% overestimate (compared to > 50% overestimate for scenario A, and a > 25% underestimate for scenario C). The overestimate in B compared to the best estimate of the total forcings is more like 5%. Given the uncertainties in the observed forcings, this is about as good as can be reasonably expected. As an aside, the match without including the efficacy factors is even better.

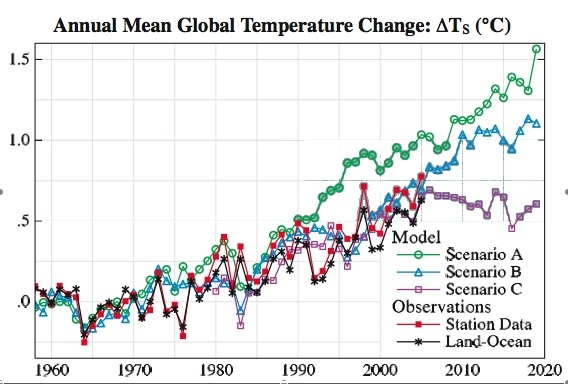

Most of the focus has been on the global mean temperature trend in the models and observations (it would certainly be worthwhile to look at some more subtle metrics – rainfall, latitudinal temperature gradients, Hadley circulation etc. but that’s beyond the scope of this post). However, there are a number of subtleties here as well. Firstly, what is the best estimate of the global mean surface air temperature anomaly? GISS produces two estimates – the met station index (which does not cover a lot of the oceans), and a land-ocean index (which uses satellite ocean temperature changes in addition to the met stations). The former is likely to overestimate the true global surface air temperature trend (since the oceans do not warm as fast as the land), while the latter may underestimate the true trend, since the air temperature over the ocean is predicted to rise at a slightly higher rate than the ocean temperature. In Hansen’s 2006 paper, he uses both and suggests the true answer lies in between. For our purposes, you will see it doesn’t matter much.

As mentioned above, with a single realisation, there is going to be an amount of weather noise that has nothing to do with the forcings. In these simulations, this noise component has a standard deviation of around 0.1 deg C in the annual mean. That is, if the models had been run using a slightly different initial condition so that the weather was different, the difference in the two runs’ mean temperature in any one year would have a standard deviation of about 0.14 deg C., but the long term trends would be similar. Thus, comparing specific years is very prone to differences due to the noise, while looking at the trends is more robust.

From 1984 to 2006, the trends in the two observational datasets are 0.24+/- 0.07 and 0.21 +/- 0.06 deg C/decade, where the error bars (2) are the derived from the linear fit. The ‘true’ error bars should be slightly larger given the uncertainty in the annual estimates themselves. For the model simulations, the trends are for Scenario A: 0.39+/-0.05 deg C/decade, Scenario B: 0.24+/- 0.06 deg C/decade and Scenario C: 0.24 +/- 0.05 deg C/decade.

The bottom line? Scenario B is pretty close and certainly well within the error estimates of the real world changes. And if you factor in the 5 to 10% overestimate of the forcings in a simple way, Scenario B would be right in the middle of the observed trends. It is certainly close enough to provide confidence that the model is capable of matching the global mean temperature rise!

But can we say that this proves the model is correct? Not quite. Look at the difference between Scenario B and C. Despite the large difference in forcings in the later years, the long term trend over that same period is similar. The implication is that over a short period, the weather noise can mask significant differences in the forced component. This version of the model had a climate sensitivity was around 4 deg C for a doubling of CO2. This is a little higher than what would be our best guess (~3 deg C) based on observations, but is within the standard range (2 to 4.5 deg C). Is this 20 year trend sufficient to determine whether the model sensitivity was too high? No. Given the noise level, a trend 75% as large, would still be within the error bars of the observation (i.e. 0.18+/-0.05), assuming the transient trend would scale linearly. Maybe with another 10 years of data, this distinction will be possible. However, a model with a very low sensitivity, say 1 deg C, would have fallen well below the observed trends.

Hansen stated that this comparison was not sufficient for a ‘precise assessment’ of the model simulations and he is of course correct. However, that does not imply that no assessment can be made, or that stated errors in the projections (themselves erroneous) of 100 to 400% can’t be challenged. My assessment is that the model results were as consistent with the real world over this period as could possibly be expected and are therefore a useful demonstration of the model’s consistency with the real world. Thus when asked whether any climate model forecasts ahead of time have proven accurate, this comes as close as you get.

Note: The simulated temperatures, scenarios, effective forcing and actual forcing (up to 2003) can be downloaded. The files (all plain text) should be self-explicable.

Did you ever doubt that he was wrong ?

RealClimate has discussed the global dimming effect on the average temperature several times. Is the dimming effect (if there is any?) included in the model projections and is there a potential for a more rapid global temperature increase after hypothetical stopping of air pollution and subsequent cleaning of air?

I.e. could the observed temperature increase be mitigated by the air pollution?

GISS produces two estimates – the met station index (which does not cover a lot of the oceans), and a land-ocean index (which uses satellite ocean temperature changes in addition to the met stations). The former is likely to overestimate the true global SAT trend (since the oceans do not warm as fast as the land), while the latter may underestimate the true trend, since the SAT over the ocean is predicted to rise at a slightly higher rate than the SST.

Um… let’s see: “SAT” = surface air temperature? And “SST” = sea surface temperature? So is the idea that the satellite measurements are of the sea surface temperature, which is predicted to be cooler than the air temperature immediately above it?

(I was really confused by this passage, until I went looking elsewhere and found an explanation of “SAT”; initially, I was thinking it was some kind of shorthand for “satellite measurements.” It’s occasionally useful to unpack some of the acronyms you use…)

[Response: My bad. I’ve edited the post to be clearer. -gavin]

Another possible forcings scenario has been discussed on energy forums, namely that all fossil fuels including coal will peak by 2025. If fuel burning drives most of the forcing then the curve should max out then decline. If the model can work with sudden volcanic eruptions I wonder if it can give a result with a peaking scenario.

[Response: I’d be extremely surprised if coal peaked that soon. There is certainly no sign of that in the available reserves, but of course, you can run any scenario you like – there will be a paper by Kharecha and Hansen shortly available that shows some ‘peak’ results. – gavin]

Nice post, Gavin. One tiny question, though. You write:

“Given the noise level, a trend 75% less, would still be within the error bars of the observation (i.e. 0.18+/-0.05) [….]”

This seems a bit confusing. I would think that “75% less” than 0.24 would be 0.06, not 0.18. (Also, the comma after “less” is not really appropriate…)

Maybe something like this:

“Given the noise level, a trend with only 75% of this magnitude would still be within the error bars …”

or perhaps

“Given the noise level, a trend that was only 75% as large …”

[Response: You are correct. Edited. -gavin]

Could someone clarify the difference between this analysis and the one Eli Rabbett posted on his blog a year ago, here and here, and here?

That analysis gave me the impression that Scenario C was the closest. Is the difference the use of ‘efficacies’?

The fossil fuel supply has of coarse bean descused by IPCC but as always some disagree with the conclusions.

http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn4216

Re #5:

Oh, great, grammar police!

Re Gavin’s comment to #4:

“Peak Oil” isn’t just about running out, it’s also about production and cost. Being permanently impatient, I’m going to have a hard time waiting for Hansen, et alias’, report, but I’ll be paying careful attention to the references, and particularly the fields of study which are included. I don’t have anything against climatologists, but I expect to see economists and petroleum engineers heavily referenced in any paper that addresses “peak oil”.

It’ll also be interesting to watch electric consumption in the States in the wake of Al Gore’s slideshow and the nationwide movement to ban incandescents.

The Land-Ocean temperature trend line is below Scenario C for most of the record and the end point in your graphic – 2005. Scenario C assumed GHG forcings would stablize in the year 2000 which it clearly has not.

Extending the data out to last year – 2006 – we see the temperature trend is still below Scenario C and about 0.2C below Scenario B. I am asserting that the 1998 models over-estimate the impact on global temperature.

Since Scenario A assumed accelerating GHGs, I’m assuming we can now discard that assumption and the drastic increase in temperatures which resulted. Scenario A predicted a temperature increase of 0.95C to 2005 while global temperatures increased by about 0.55C and GHG concentrations are not accelerating.

Unless the geologists who measure these things really screwed up, coal ain’t peaking any time soon:

“Total recoverable reserves of coal around the world are estimated at 1,001 billion tons – enough to last approximately 180 years at current consumption levels”

Now, China is certainly ramping up coal consumption, but not that fast.

If the world was running out of coal, there would be a lot more attention on nukes, wind, etc.

Great article. Thank you for writing it. I cross posted about this article on my site (http://www.globalwarming-factorfiction.com) but I thought I would make a few comments here as well. I have encouraged all of my readers to regularly come to RealClimate since I respect much of what is written here.

My readers know that I frequently call for more research and better modeling techniques on the issue of global climate change and global warming. It is something that I think is necessary before our governments spend billions or trillions of dollars to change behavior.

I think public discussion on this subject is very important and encourage more scientists to do this outside of the veil of the scientific community. My concerns about the accuracy of models are confirmed with this analysis – the 3 models that are described in the first analysis are off by 50%, 10% and 25%.

It is interesting that even the observed measurement has some ambiguity in it since there is no “standard” way of measuring global averages. This is yet another way for models to not be precise enough since we don’t have a golden standard to live up to.

There is an often repeated saying “Close enough for government work.” In this case, I think we should hold the politicians to a higher standard and we need to have models that can more accurately predict observed occurrences. Many of you will be familiar with another saying “Close only counts in horseshoes and hand grenades.”

Once again, great article. Thank you for writing on this subject.

[Response: Umm…. you’re welcome. But basically you are saying that nothing will ever be good enough for you to be convinced. The 3 forcing scenarios are nothing to do with the model – they come from analyses of real world emissions and there will always be ambiguity when forecasting economics. Thus a spread is required. Given the scenario that came closest to the real world, the temperatures predicted by the model are well within the observational uncertainty. That is, even if you had a perfect model, you wouldn’t be able to say it was better than this. That is a purely empirical test of what is ‘good enough’ – and not just ‘for government work’ (which by the way is mildly offensive). How could it do better by this measure? Perhaps you would care to point to any other predictions of anything made in the mid-1980s that are as close to the obs as this? – gavin]

Not every one is convinced that there’s that much coal left,

http://globalpublicmedia.com/richard_heinbergs_museletter_179_burning_the_furniture

Richard Heinberg’s Museletter #179: Burning the Furniture | Global Public Media

Re # 9 John Wegner: “The Land-Ocean temperature trend line is below Scenario C for most of the record and the end point in your graphic – 2005…..

I am asserting that the 1998 models over-estimate the impact on global temperature.”

Apparently you missed this passage in the original:

“The former is likely to overestimate the true global surface air temperature trend (since the oceans do not warm as fast as the land), while the latter may underestimate the true trend, since the air temperature over the ocean is predicted to rise at a slightly higher rate than the ocean temperature. In Hansen’s 2006 paper, he uses both and suggests the true answer lies in between.”

re: 9. “Extending the data out to last year – 2006 – we see the temperature trend is still below Scenario C and about 0.2C below Scenario B. I am asserting that the 1998 models over-estimate the impact on global temperature.”

Except it appears that your assertion does not consider, as stated above, that:

“In these simulations, this noise component has a standard deviation of around 0.1 deg C in the annual mean. That is, if the models had been run using a slightly different initial condition so that the weather was different, the difference in the two runs’ mean temperature in any one year would have a standard deviation of about 0.14 deg C., but the long term trends would be similar. Thus, comparing specific years is very prone to differences due to the noise, while looking at the trends is more robust.”

Gavin,

I have no doubt that your statement “Thus when asked whether any climate model forecasts ahead of time have proven accurate, this comes as close as you get” is correct. Just as I am sure that somewhere in the range of the IPCC projections (or “forecasts” if you prefer), lies the true course of temperature during the next 20-50 years or so (and maybe longer). In hindsight, we’ll be able to pinpoint which one (or which model tweaks would have made the projections even closer), just as you have done in your analysis of Hansen’s 1988 projections. Projections are most useful when you know in advance that they are going to be correct into the future, and are not so much so (especially when they encompass a large range of possibilities) when you only determine their accuracy in hindsight. Surely knowing in 1988 that for the next 20 years the global forcings (and temperatures) were going to be between scenarios B&C rather than closer to scenario A would have been valuable information (more valuable then, in fact, than now). Given that the forcings from 1984 to present (as well as the temperature history) lie at or below the low end of the projections made in 1988, do you suppose that this will also prove to be true into the future? If so, don’t you think this is important information? And that perhaps some of the crazier SRES scenarios on the high side should have been discounted, if not in the TAR, then definitely in AR4?

-Chip

to some degree, supported by the fossil fuels industry since 1992

[Response: Chip, Your credibility on this topic is severely limited due to your association with Pat Michaels. Hansen said at the time that B was most plausible, and it was Micheals (you will no doubt recall) who dishonestly claimed that scenario A was the modellers’ best guess. It would indeed have been better if that had not been said.

However, I’d like to underline the point that the future is uncertain. A responsible forecast must take both a worst case and best case scenario, with the expectation that reality will hopefully fall in between. Most times it does, but sometimes it doesn’t (polar ozone depletion for instance was worse than all scenarios/simulations suggested). Your suggestion that we forget all uncertainty in economic projections is absurd. I have much less confidence in our ability to track emission scenarios 50 or 100 years into the future than I have in what the climate consequences will be given any particular scenario, and that is what underlies the range of scenarios we used in AR4. I have previously suggested that it would have been better if they had come with likelihoods attached – but they didn’t and there is not much I can do about that. -gavin]

Re #10:

Again, having the fuels in the ground doesn’t mean anyone can afford to get them OUT of the ground.

This is the note that always gets in the way —

“3 Proved reserves, as reported by the Oil & Gas Journal, are estimated quantities that can be recovered under present technology and prices.”

My recollection is that Kyoto (?) assumed $20/bbl oil. Seen that lately? Think you’ll see it any time soon?

Here’s the next one —

“9 Based on the IEO2006 reference case forecast for coal consumption, and assuming that world coal consumption would continue to increase at a rate of 2.0 percent per year after 2030, current estimated recoverable world coal reserves would last for about 70 years.”

The IEO2006 paper forecasts having NO remaining fossil reserves, and basically being bankrupt in 2077. Those last few years of production are going to be unaffordable to all but the heirs of Bill Gates and Sam Walton.

The IEO2006 paper also assumes a quadrupling of Chinese coal consumption. That behavior is going to have to contend with this problem — whether that was their goal or not, the skies over China are now so dirty that our spy satellites can’t even see the ground over many cities. Here is a bigger image. I don’t see China sustaining growth in air pollution for too many more years.

In addition to rapidly declining air quality — as shown by those satellite images of China — the IEO2006 paper ignores the rising costs of energy as a fraction of living expenses. Just about everything we buy includes “energy” as a cost.

I understand that large estimates of recoverable fossil fuels are central to making a case for the risks of burning those fuels, but the longer term risk, if we manage to survive burning everything we’ve got in the ground, is taking a path that is completely dependent on those fuel sources and finding ourselves living on a baked planet with no energy to do anything about it.

And yes, I realize the driving issue is economics, not total reserves, but I don’t see coal becoming uneconomic any time soon (I wish it would).

“There have however been an awful lot of mis-statements over the years – some based on pure dishonesty, some based on simple confusion.”

For a side by side comparison of Pat Michaels ‘confusion’ please go here:

Logical Science’s analysis of Pat Michaels

It amazes me that this is the most interviewed commentator by a factor of two on CNN.

A minor point: Hansen first presented these projections in his November 1987 Senate testimony. It didn’t receive much attention, which is why they decided to hold the next hearings during the dead of summer.

Regarding peak coal, there seems to be some disagreement about this. For example, this report puts the worldwide peak (not US peak) between 2020 and 2030: http://www.energywatchgroup.org/files/Coalreport.pdf

Re # 8

Thank goodness for so-called ‘grammar police’ within this forum to remind everyone of the importance of tight wording.

Legal cases too often ‘fall over’ on technicalities even this small.

Indeed countries have gone to war over differing interpretations of rights implied to them by a single preposition in a treaty or declaration.

I’m curious about whether the model has been run out into the future for several hundred years? Do these models fall apart outside some time range or just level off (as the distance from the forcing grows)? Thanks for any insight on this.

[Response: Yes they have. They don’t fall apart, but they do get exceptionally warm if emissions are assumed to continue to rise. However, on those timescales, physics associated with ice sheets, carbon cycle, vegetation changes etc. all become very important and so there isn’t much to be gained by looking at models that don’t have that physics. – gavin]

How much of an effect did the stabilization of methane concentrations have on forcing changes? My rough estimate indicates that if methane concentrations had continued to rise at their 1980s rate, that would have led to more than a 0.05 W/m2 over observations. And if Bousquet et al. (2006) are correct about the stabilization being a temporary artifact of wetland drying, then future forcing might jump up again. (if on the other hand it is a result of reduced anthropogenic emissions from plugging natural gas lines, changes in rice paddy management in China, landfill capping in the EU and US, etc. – then maybe we’ve been more successful at mitigation this past decade than is otherwise estimated)

Also, in response to FurryCatHerder: I work with energy economists. All of them believe that at prices near $100/barrel, so many otherwise marginal sources become profitable (tar sands, oil shale, coal to liquids, offshore reserves, etc.) that those present an effective cap on price increases for many decades. And $100/barrel is not yet high enough to really put much of a dent in demand. Mind you, they all think that there is good reason to reduce fossil fuel use as early as possible in any case… but more for climate, geopolitical, and other environmental reasons…

Hansen first presented these projections in his November 1987 Senate testimony. It didn’t receive much attention, which is why they decided to hold the next hearings during the dead of summer.

And that was an extremely hot and dry summer for most people was it not? I distinctly remembering that I discovered that the only thing between me and total agony, was my very extensive deciduous black walnut, maple and oak leaf cover. There is a really big difference between total scorch, and the greatly reduced temperatures, and the elevated oxygen and humidity of the decomposing forest floor. It will be interesting to see what this summer brings for us.

I just don’t see how we can recover from this with anything less than a complete technological breakthrough solution, as it appears we are already too over extended technologically on this planet. It’s going to require people to adjust their critical thinking in far more ways than just energy reduction. Is the average joe American scientist capable of this sort of creative out of the box thinking? From what I’ve seen thus far, no. At least not with this administration.

Re. 11.

Gavin – perhaps I wasn’t clear. I thought this was great effort for a rather old model and surely advances in technology should be able to improve on this.

However, as a mechanical engineer (no longer practicing), industry would never design a product that had such a high error rate as the result would be a guaranteed lawsuit and likely loss of life. From a scientific POV, this may be acceptable but politicians are using this kind of data to create legislation that will cost billions and likely cost lives in hopes of saving lives. The error rate is simply to large to make that kind of investment. We need to invest in better research and better models before that kind of investment is justified. Showing 3 graphs and finding that one is “kind of” correct and therefore could be used 50-100 years later is bad engineering. If a model cannot get within a few percentages on an average for a 15-20 year test than how off will it be for 2100?

The Wall Street Journal said that I was a semi-skeptic and that is pretty accurate. I speak to both sides of this argument on my site http://www.globalwarming-factorfiction.com. I am willing, ready, and anxious to “believe” but I need better math than I have seen so far. If I saw decent math to getting to the conclusions than I am willing to invest the multi-billions (and the toll in lives that will be lost due to the decline in treasure) that it will be required to fix the problem.

This site is great because it gives some very compelling arguments on the climate. We simply need to invest more in getting better science.

[Response: But what is your standard for acceptable? My opinion, judging from the amount of unforced (and hence unpredictable) weather noise is that you would not have been able to say that even a perfect model was clearly better than this. Think of it was the uncertainty principle for climate models. After another 20 years we’ll know more, but as of now, the models have done as well at projecting long term trends as you can possibly detect. Thus you cannot have a serious reason to use these results to claim the models are not yet sufficient for your purpose. If you will not make any conclusion unless someone can show accurate projections for 100 years that are within a few percent of reality then you are unconvincible (since that will never occur) and thus your claim to open-mindedness on this issue is a sham. Some uncertainty is irreducible and you deal with that in all other aspects of your life. Why is climate change different? As I said, point me to one other prediction of anything you like that was made in the mid-1980s that did as well as this. – gavin]

> industry would never design a product that had such a high error rate

> as the result would be a guaranteed lawsuit and likely loss of life.

Who did design the current technology?

Re comment 24 by Sean O.:

This is just the old argument that we can’t do anything until we are certain. The fallacy in that argument was, and still is, that we are doing something to change the radiative behavior of the atmosphere. The appropriate response, without knowing more, other things being equal, would be to stop that right now, but I don’t suppose that you proose closing down all fossil fuel emissions until the science is better understood.

Gavin,

Thanks for the response. As far as my “credibility” on the issue as addressed in my comment (#15), I was largely paraphrasing your results. I wasn’t relying on credibility to make my point, thus my association with Pat Michaels (and, for full disclosure, my boss) doesn’t seem to impact the contents of my comment–that it is easy to take credit in hindsight for a correct forecast, but, if you can’t use it to reliably identify a future course, than it is of little good. You seem to be of the mind that Dr. Hansen was able to reliably see the future (or at least 20 years of it) in his scenario B, so, what is your opinion about the next 20 years? Did Dr. Hansen’s Scenario A serve any purpose? Does IPCC SRES scenario A2? A1FI? If Dr. Hansen never imagined Scenario A as being a real possibility for the next 20 years, I guess indicated by his description “Scenario A, since it is exponential, must eventually be on the high side of reality in view of finite resource constraints and environmental concerns, even though the growth of emissions in Scenario A (~1.5% yr-1) is less than the rate typical of the past century (~4% yr-1)” then his subsequent comment (PNAS, 2001) “Second, the IPCC includes CO2 growth rates that we contend are unrealistically large” seems to indicate that Dr. Hansen doesn’t support some of the more extreme SRES scenarios. Am I not correct in this assumption?

I guess the point of your posting was that IF we know the course of the actual forcing, climate models can get global temperatures pretty well. But you go beyond that, in suggesting that Dr. Hansen knew the correct course of the forcing back in 1988. Isn’t that what you meant in writing “Thus when asked whether any climate model forecasts ahead of time have proven accurate, this comes as close as you get.”?

So, in the same vein, which is the IPCC SRES scenario that we ought to be paying the most attention too (i.e. the one made “ahead of time” that will prove to accurate?)

-Chip Knappenberger

to some degree, supported by the fossil fuels industry since 1992

It’s amazing how our politicians can tell the truth while maintaining deniability:

___________________________________

Yesterday, White House spokesman Tony Snow said Bush wants new regulations because “you’ve got a somewhat different atmosphere now, ….”

Ok . A hypothetical math question.

Let’s say for argument’s sake we wanted to achieve a certain global temperature in , say , 25 years.

Given the track record of Government, what are the chances that could be achieved?

I’d say almost zero.

[Response: Nothing to do with the government. If the temperature rise was not around 0.5 deg C warmer than today, it would not be achievable under any circumstances. However, radically different outcomes will be possible by 2050, and certainly by 2100. – gavin]

Gavin–thank you for this post. As a physics student very much used to operating on the “make prediction; test prediction” model of determining the reliability of a theory, I appreciate thorough discussion of realistic expectations for these climate models. One question I would ask, being a non-specialist, is what the models gain us over a, say, “straight curve-fitting” approach in the first 10-20 years regime you examine here. For example, just looking at these graphs, I feel like I could have drawn in 3 lines (A,B,C) by hand, based on what seems plausible given recent trends, and be reasonably confident that the near future would lie somewhere within those predictions (and statistically, maybe even land right on one of them). Is this the case? Of course, I wouldn’t expect to be able to do that for 50 to 100 years, which is the interesting timescale for global warming.

[Response: For a short period, the planet is still playing “catch up” with the existing forcings, and so we are quite confident in predicting an increase in global temperature of about 0.2 to 0.3 deg C/decade out for 20 years or so, even without a model. But the issue is not really the global mean temperature (even though that is what is usually plotted), but the distribution of temperature change, rainfall patterns, winds, sea ice etc. And for all of those elements, you need a physically based model. As you also point out, that kind of linear trend is very unlikely to be useful much past a couple of decades which is where the trajectory of forcings we choose as a society will really make the difference. – gavin]

Congrats Gavin, it puts recent intellectual crimes to light. How can anyone especially top-level scientists, and sometimes the odd science fiction book writer, come to any conclusion that GCM’s are bunk? It would be good to constantly refer this site to any prospective journalist or blogger inclined to devote some ink to the regular “arm chair” contrarian scientist, usually equipped with a snarky philosophy rather than facts. The basic contra GCM argument is dead.

Great to see this revisited in this way. It’s something that comes up a lot in our workshops with teachers. I think it’s worth pointing out that the GCM in EdGCM is the GISS Model II, the same as was used by Hansen et al., 1988. Thus, anyone who can download and run EdGCM (see link to the right) can reproduce for themselves Hansen’s experiments. The hard-coded trends are now gone, but it’s easy to create your own, and you can try altering the random number seed in the Setup Simulations form to create unique experiments for an ensemble (as Gavin mentions, this wasn’t done for the orginal 1988 paper). The only differences in the GCM are a few bug fixes related to the calculation of seasonal insolation (a problem discovered in Model II in the mid-1990’s) and an adjustment to the grid configuration that makes Model II’s grid an exact multiple of the more recent generations of GISS GCMs (like Model E).

29.

I’m not following. How will radically different outcomes be possible?

[Response: By controlling emissions of CO2, CH4, N2O, CFCs, black carbon etc. By 2050, a reasonable difference between BAU (A1B) and relatively aggressive controls (the ‘Alternative Scenario’) could be ~0.5 deg C, and by 2100, over 1 deg C difference. And if we’ve underestimated sensitivity or what carbon cycle feedbacks could do, the differences could be larger still. – gavin]

An interview with renowned climate scientist James Hansen | By Kate Sheppard | Grist Main Dish 15 May 2007

http://www.grist.org/news/maindish/2007/05/15/hansen/index.html?source=daily

In my January 31, 2006 letter to the U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC) Office of Inspector General (IG) I requested the DOC IG to see to it that NASA oversee NOAA on climate change and global warming (comment 1).

http://npat1.newsvine.com/_news/2007/05/15/720628-an-interview-with-renowned-climate-scientist-james-hansen-by-kate-sheppard-grist

Re: 24

Choose any mathematical scenario you like. They range from bad to catstrophe. Hansen provided 3 emissions scenarios to bracket what was likely, based on models that are now 20 years old. The results were as accurate as anyone could have hoped for. Yet, somehow, for some reason, that isn’t good enough. No one is going to be able to predict what actual emissions of the various greenhouse gases will be over the next 100 years. No one will be able to predict what volcanic activity there will be. We do not understand all of the possible feedbacks, but the more we know, the worse it looks. The only way the models can be substantially wrong is if there is an unknown feedback that will swoop in and negate all of the warming in the nick of time. Only a fool would delay policy action based on such a “hope.” We know the basic mechanisms well enough to know that doing nothing is a recipe for disaster.

And please, the idea that industry always carefully weighs the cost to society is a bit silly. How many decades did it take the tobacco industry to admit in public what their own scientist knew about their products? How many people died during this time? How aggressive did the autocompanies persue safety? Did it really take until the mid ’60s to recognize the importance of seatbelts? Delay, delay, delay.

RE 15 & 27

Chip:

There are many who read the comments and replies contained here who are not “in the business” and who cannot readily discern what comments come from what side of the issue.

Note how Gavin included complete disclosure in his first paragraph about Dr. Hansen being his boss. Then note how you faild to do so, about your boss, Pat Michaels until Gavin pointed it out.

Why did you do that? Was it merely an oversight? Or was it an attempt to lessen the impact of your association with your boss who has been convincingly exposed as being willing to manipulate the findings of others for what appears to be a predetermined political/economic goal?

I cannot convince myself you simply forgot to disclose this important information, after all this is the type of communication you do all the time and you know how important the perception of bias is in any debate.

So Gavin scores points on the “credibility scale” and in my ledger you have lost a few.

Steve Horstmeyer

Steve (re comment 36):

For 1, the contents of my comment 15 was in no way dependent on my association with Pat Michaels (reread the comment to see for yourself). I agreed with Gavin’s analysis about which scenario was closest to the observations, but quibbled with his underlying sentiment that this was known to be the case in 1988. And if so, wondered if we knew the most likely pathway for the next 20-50 years (my guess was that it does not include the extreme IPCC SRES scenarios such as A2).

For 2, I included my usual disclaimer about being funded by the fossil fuels industry (in an attempt to head off replies to my comments being dominated by folks pointing out that association)

For 3, I sort of thought it was common knowledge that I work for Pat Michaels (perhaps I need to add this to my disclaimer as well)

For 4, I repeat my first point…my comment 15 was in no way a defense of Pat Michaels, it had to do with hindsight v. foresight. True I am keenly aware of the contents of Hansen 1988 because of my work for Pat, and thus, I guess have a tendency to comment on them.

If my failure to point out my association with Pat (or even simply that an association with him exists, whether pointed out or not) severly reduces my “credibility” so be it. But rarely do I invoke credibility in my comments. If you don’t believe what I am saying, then look it up. I try to include quotes and references to help you (and others) in their ability to cross-check what I am commenting on.

-Chip Knappenberger

to some degree, supported by the fossil fuels industry since 1992

and Pat Michaels is my boss

re 35: just a sidebar tidbit — in 1956 Ford made a great corporate effort to push safety. Resulted in the industry saw, “Ford sold safety; Chevy sold cars!”

Just wondering what you use for initial conditions. Seems like a shame to waste processors doing ten years simulated time waiting for the transients to settle down so you can pick out the secular trend. Not that there’s necessarily a better way of doing it.

I’d look in the paper to find out but I’m assuming the article’s not in the open access literature.

Thanks,

Peter

[Response: It’s available. Just follow the link. (The answer is at the end of a 100 year control run). – gavin]

Re: 24: “industry would never design a product that had such a high error rate as the result would be a guaranteed lawsuit and likely loss of life.”

The climate system was not built by industry.

Just like the San Andreas fault was not built by industry and models do not accurately predict when, where and how big quakes will be. The San Andreas fault is far less predictable than the climate, but it does not stop industry from proceeding with operations using building and other specifications that are (hopefully) designed to take account of and minimize the risks involved in building near an active fault line.

If the geophysics science community were to come to the conclusion that something we are doing was 90% likely to be significantly, and irreversibly increasing the frequency and strength of damaging earthquakes, would industries insist that they be able continue to do it until the frequency, strength and timing of quakes could be predicted with precession? Obviously not. Why then is this course of action OK with the Climate?

Re: 24.

We know we need to transition to renewable energy sources – this must happen in the next century regardless of climate change. But the potentially severe impacts of a quickly warming world up the ante; therefore, though the model predictions have significant error bars, a risk management perspective demands that significant mitigations steps be taken immediately. Gavins analysis, posted here, serves to further support this conclusion.

An analogy: Hurricanes approaching the Gulf coast pose a threat to refineries. These refinereries have safe opertating limits w/ respect to wind and water; a full shut down requires more than 24 hours to accomplish and millions of dollars. If forecasters and consultants present them w/ a roughly 10% likelihood of exceeding those limits w/in roughly 36 hours, the refineries will shut down. From a risk management perspective they deem the multi-million dollar shutdown cost a reasonable investment, based on a 10% threat likelihood. (These figures are approximate.)

While it’s more difficult to assign a percentage-level threat to severe climate change risk, the stakes are infinitely higher. Taken in total, the vast majority of evidence suggests that anthropogenic forcings are now dominant and that human impact over the next century will be significant, possibly catastrophic. From the standpoint of policy, it’s not about certainty, but risk management.

Could you please do a reprint of the figure this time adding Error Bars.

there is absolutely no point in trying to see if the “real” data (actually data that has been through the sausage machine a few times) and the models.

just how big are the Error Bars in each of the scenarios?

Re. #18

Has an academic study been done that proves that he is? (If not, where does your 2:1 figure come from?)

Also, have any academic studies been done that show similar conclusions about other contrarians?

And have any academic studies been done that show what proportion of press/media coverage of global warming is sympathetic to the argument that it is anthropogenic and serious, what proportion is antipathetic to that argument, and what proportion is neutral; and how the proportions have altered over recent years?

Today I felt like I walked out of the house and into an oven. If this is the 0.5 degree difference over 20 years, I would say we are in big trouble. This reminds me of those nightclubs with the second rate band and then a fire breaks out. At first, the people find it amusing and cool, then it gets out of control and there is panic and the eventual end is many many charred bodies and tragedy. Right now we are in the amused stage of this proverbial fire and are observing and trying to figure this out. Wait until the real burning and panic, that will eventually come. All I can do is sit outside on the porch and have a beer and wonder where all the bees are. Our only hope is a quantum paradigm shift which is a possibility. We need to save our grandchildren.

I think this response by James Hansen was a highlight of the interview (#34).

While not a scientist, I clearly understand that fossil fuels emits greenhouse gases, though the degree of warming are obviously open for heated debate and frankly, a lot of not so friendly jabs on this and other sites. What appears not to be understood is that despite someone’s prior posting, the extraction of fossil fuels is already getting more difficult and expensive, and will continue to do so. Coal and gas costs are already significantly higher than would have been suggested a number of years ago with additional taxes, and it is a foregone conclusion that regulations will be passed to get those costs even higher.

My point, I have no faith that anything short of a technological breakthrough is going to reverse the growth of CO2. The world had less than 1 billion people in 1750, 4 billion when we had the coldest temperatures in the 70’s, over 6 billion now, and forecasted at over 9 billion somewhere down the road. Even if we significantly slow the burning of fossil fuels, does anyone really expect CO2 to go down? All these people breathe, clear land to live, and will burn some fossil fuels. What the US does to control emissions will have no significant effect.

I have faith that science and technology will develop the answers we need, but it will take time. Think outside of the box and quit pointing fingers.

> industry would never design a product …

It’s worth remembering that each improvement in the earthquake building codes has been opposed by industry on the basis that it wasn’t likely that another bad earthquake would happen, and it would cost too much, and not be economical.

This is well studied. So is the process of getting improvements made:

“… Promoting seismic safety is difficult. Earthquakes are not high on the political agenda, because they occur infrequently and are overshadowed by more immediate, visible issues. Nevertheless, seismic safety policies do get adopted and implemented by state and local governments. …The cases also show the importance of post-earthquake windows of opportunity…. The important lesson is that individuals can make a difference, especially if they are persistent, yet patient; have a clear message; understand the big picture; and work with others.

(c) 2005 Earthquake Engineering Research Institute”

http://scitation.aip.org/getabs/servlet/GetabsServlet?prog=normal&id=EASPEF000021000002000441000001&idtype=cvips&gifs=yes

1. Gavin is looking at the forcings, I was looking at the mixing ratios in most of my posts, but did show the forcings from the follow up 1998 PNAS paper in a later one. You could make an argument from the 1998 paper that C was “slightly better” at the time, but, of course well within the natural variability, besides which forcings in the early 1990s may have been decreased by the collapse of the Soviet Union, Pinatubo, etc. There may be compensating differences in how the forcings were calculated in the 1988 paper and the difference between the scenarios for the mixing ratios and what actually happened.

2. Hansen clearly explained that in the near run (a few decades), climate sensitivity is not very important:

“Forecast temperature trends for time scales of a few decades or less are not very sensitive to the model’s equilibrium climate sensitivity (reference provided). Therefore climate sensitivity would have to be much smaller than 4.2 C, say 1.5 to 2 C, in order for us to modify our conclusions significantly.”

3. One answer to Knappenberger’s rather childish comment –gee how could Hansen know the future– is, of course, that the three scenarios were chosen to bracket the possible, to explore the range of what could happen, and the middle scenario was the built to be the most likely. So Chip is miffed that what was thought to be most likely did happen. Well he might be, as it shows that the reasonable emission scenarios can be built. The other answer is Thomas Knutson’s reply to a rather similar attempt by Pat Michaels:

“Michaels et al. (2005, hereafter MKL) recall the question of Ellsaesser: “Should we trust models or observations?” In reply we note that if we had observations of the future, we obviously would trust them more than models, but unfortunately observations of the future are not available at this time. “

Re: Think outside the box. We have a vast quantity of cold, nutrient-rich water below 1000-meter depth. We have solar energy stored in the surface of the tropical ocean to act as a source for a heat engine. The heat sink is the cold bottom water which the heat engine can pump up to cool the ocean surface and the overlying atmosphere. We use some of the power to spread the cold water over the surface so that it does not sink below the layer where phytoplankton convert dissolved CO2 into organic matter that increases the mass of their bodies to feed other ocean creatures. The pumping brings up macro- and micro-nutrients required for photosynthesis, which otherwise can’t get through the thermocline in the tropical ocean. This increases the primary production of the tropical ocean and helps to repair the damage of overfishing. Using CO2 to create organic phytoplankton mass leaves less CO2 to acidify the ocean and interfere with formation of calcium carbonate shells and skeletons.

Have the forcings from 1959 to present been growing exponentially or linearly? I had the impression that, with the growth or China and India, at least the CO2 forcings had been growing exponentially. Certainly the graph of CO2 levels at NOAA doesn’t look linear. If the growth has been exponential, then shouldn’t Scenario A be the scenario being testing against?